Non-uremic calciphylaxis associated with alcoholic hepatitis: A case report

Yasser M Sammour, Haitham M Saleh, Mohamed M Gad, Brayden Healey, Melissa Piliang

Abstract BACKGROUND Calciphylaxis is a form of vascular calcification more commonly associated with renal disease. While the exact mechanism of calciphylaxis is poorly understood,most cases are due to end stage kidney disease. However, it can also be found in patients without kidney disease and in such cases is termed non-uremic calciphylaxis for which have multiple proposed etiologies.CASE SUMMARY We describe a case of a thirty-year-old morbidly obese Caucasian female who had a positive history of alcoholic hepatitis and presented with painful calciphylaxis wounds of the abdomen, hips, and thighs. The hypercoagulability panel showed low levels of Protein C and normal Protein S, low Antithrombin III and positive lupus anticoagulant and negative anticardiolipin. Wound biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of non-uremic calciphylaxis in the setting of alcoholic liver disease. The calciphylaxis wounds did not improve when Sodium Thiosulfate was used alone. The patient underwent a series of bedside and surgical debridement. Broad spectrum antibiotics were also used for secondary wound bacterial infections. The patient passed away shortly after due to sepsis and multiorgan failure.CONCLUSION Non-uremic Calciphylaxis can occur in the setting of alcoholic liver disease. The treatment of choice is still unknown.

Key words: Calciphylaxis; Alcoholic hepatitis; Vascular calcification; Sodium thiosulfate;Debridement; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Calciphylaxis is a form of vascular calcification commonly associated with renal disease. Patients diagnosed with calciphylaxis usually face an unfavorable prognosis with most patients dying within 12 mo of diagnosis[1]. Although rare, calciphylaxis has an incidence rate of 35 per 10000 patients in the United States with around 70% of the patients being females and the average age of diagnosis being at 50-70 years[1]. The vascular calcification in calciphylaxis results in ischemic skin lesions that are very painful, treatment resistant, and predisposed to bacterial infections. Most patients with calciphylaxis have a diagnosis of end stage renal disease or other forms of kidney dysfunction including chronic kidney disease, kidney transplantation, or acute kidney injury. Some studies have reported calciphylaxis in patients with normal kidney function, termed non-uremic calciphylaxis[2,3]. Other non-uremic causes of calciphylaxis reported in the literature included primary hyperparathyroidism,malignancy, connective tissue disease, and liver disease[1]. As the main clinical manifestation associated with calciphylaxis, the cutaneous lesions can range from minor painful induration to skin necrosis[3].

CASE PRESENTATION

A thirty-year-old Caucasian female was transferred to our medical center for further management of painful wounds of the abdomen, hips, and thighs. She had a past medical history of alcoholic hepatitis, diagnosed four months earlier with a liver biopsy that showed steatohepatitis and stage 3 fibrosis rather than cirrhosis, and morbid obesity (BMI = 56) status post Roux-en-Y gastric bypass done twelve years ago (unknown pre-surgical BMI). History was negative for diabetes mellitus, kidney dysfunction, autoimmune diseases, hyperparathyroidism or Warfarin intake.

And then they arrived --- the minister s family and all my relatives in a clamor of doorbells and rumpled8 Christmas packages. Robert grunted9 hello, and I pretended he was not worthy10 of existence.

Eight weeks after the onset of alcoholic hepatitis, the patient developed tender erythema on her abdomen, hips, and thighs, which evolved into painful firm subcutaneous nodules.

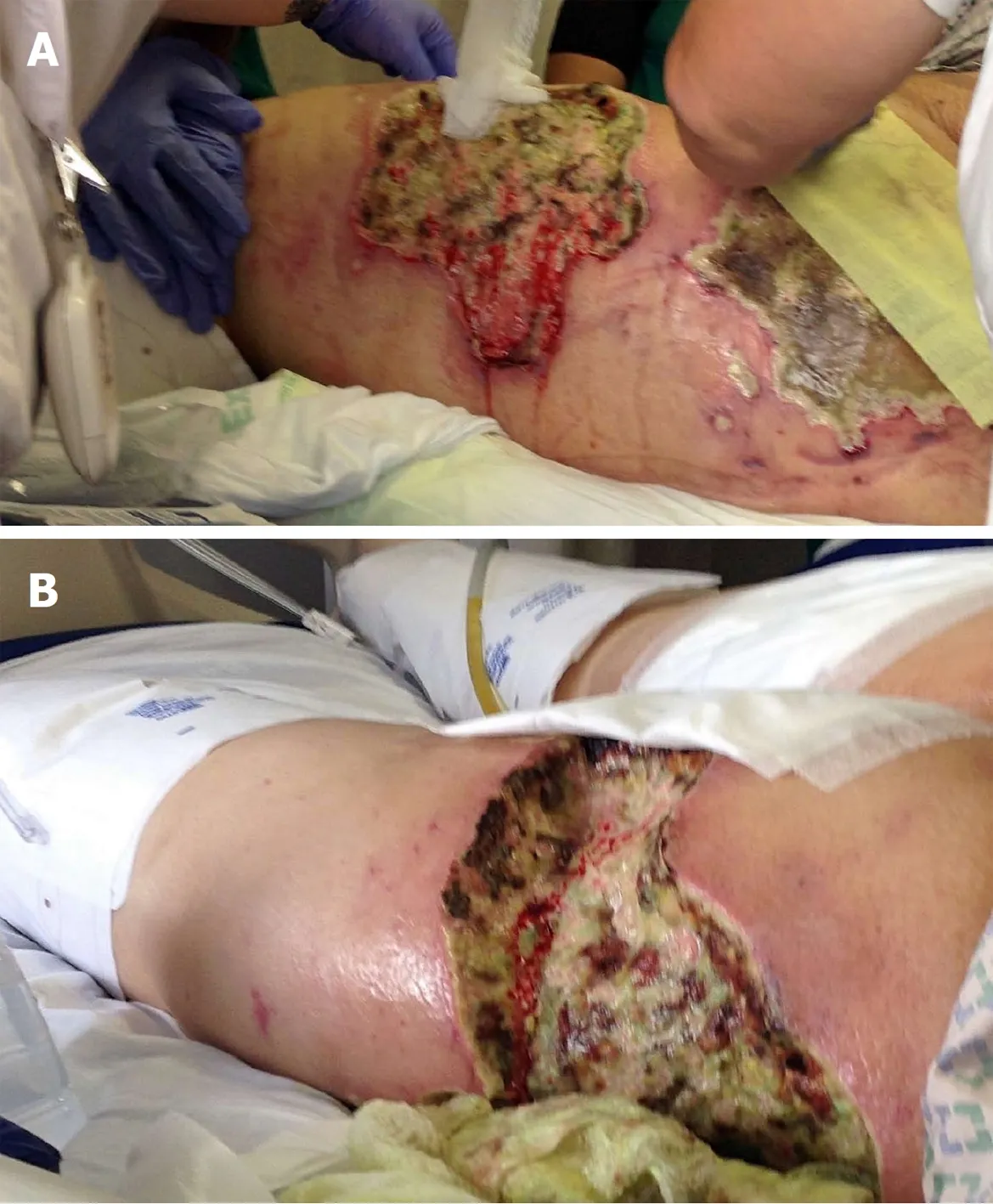

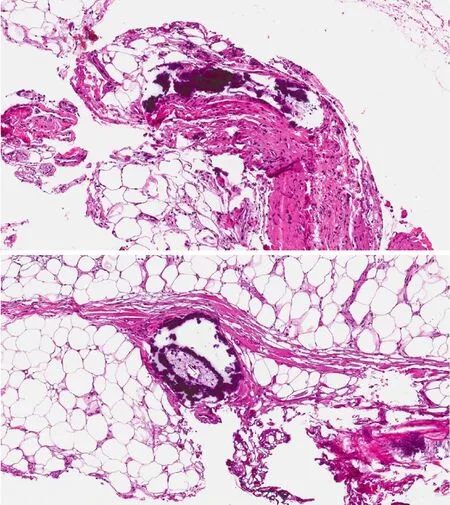

On admission to our hospital, vital signs were notable for temperature 36.7 °C (98.1°F), blood pressure 98/41 mmHg, pulse 119 bpm, and respiratory rate 20/min.Physical examination showed woody, indurated, exquisitely tender erythematous plaques on the abdomen, hips, and thighs, with central stellate necrotic eschar and purpura (Figure 1A). She also had anterior abdominal wall edema and bilateral lower extremity pitting edema. Laboratory workup was significant for leukocytosis 24 ×109/L , with absolute neutrophil count 21.5 × 109/L , hemoglobin 7.2 g/dL, MCV 87.5 fL, total protein 6.1 g/dL, albumin 1.7 g/dL, AST 56 U/L, ALT 19 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 172 U/L, total bilirubin 1.8 mg/dL, PT 17.7 s, INR 1.6, APTT 37.3, BUN 15 mg/dL, creatinine 1.32 mg/dL, calcium 8.2 mg/dL, phosphorus 3.9 mg/dL, PTH 22 (normal), and 1,25 OH Vit D3 5.8 (low). The hypercoagulability panel showed low levels of Protein C 33 IU/dL (normal: 76-147), low normal levels of protein S 67 IU/dL (normal: 65-135), low antithrombin III levels, positive lupus anticoagulant and negative anticardiolipin. Wound biopsy showed dermal hemorrhage, dermal vascular occlusion, calcium deposition within the walls of large veins and the surrounding adipose tissue (Figure 2). These pathologic findings, correlated clinically, were most consistent with non-uremic calciphylaxis in the setting of alcoholic liver disease.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The abdomen and thighs are the commonest predilection sites for calciphylaxis lesions due to higher adipose tissue density. The lesions present as indurated plaques or nodules that may have ulcerations and eschar and can be associated with livedo reticularis[10]. A tissue biopsy is essential to confirm the diagnosis[11,12]. Histopathologic changes are similar in both uremic and non-uremic calciphylaxis. Microscopic findings include calcification of dermal vessels and diffuse dermal thrombi. Dermal angioplasia was frequently reported[13]. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum-like changes were also reported and described as thickened, fragmented and curled elastic fibers[14].

TREATMENT

Not a breath of wind moved, not a leaf stirred, all was silent as the grave, only on the still bosom of the lake thirty ducks, with brilliant plumage, swam about in the water

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Edward s heart soared with joy as he spent the next month trying to make the cabin into a home. At last, the day he had been waiting for his whole life arrived. With a bouquet5 of fresh-picked daisies in hand, he left for the train depot(,). Steam billowed and wheels screeched6 as the train crawled to a stop.

DISCUSSION

He remembered such days from his own childhood in the mountains, rare moments of escape when he went into the woods, his breathing amplified74 and his voice somehow muffled75 by the heavy snow that bent branches low, drifted over paths

Gastric bypass surgery can also predispose to Vitamin D and Calcium deficiency with secondary hyperparathyroidism due to alterations in the digestive anatomy which could set up a suitable environment for calciphylaxis[9].

We present a patient with alcoholic liver disease and low normal levels of protein C who developed calciphylaxis and died shortly thereafter from related complications.

Liver dysfunction can lead to low levels of coagulation inhibitors, specifically protein C and S, which can lead to vascular injury[6]as well as thromboembolic manifestations such as deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Another theory behind the link between liver dysfunction and calciphylaxis could be related to Fetuin-A which is a protein synthesized in the liver that acts as a circulating inhibitor of vascular ossification-calcification. Its effects are mediated by ‘‘calciprotein particles’’, which clear the circulating calcium and phosphorus, and therefore selectively inhibit vascular ossification-calcification without affecting the bone mineralization. Another inhibitor of that pathway is the Matrix-GLA-Protein (MGP).Activated MGP, through Vitamin K dependent carboxylation, forms a complex with fetuin-A which inhibits the Bone-Morphogenetic-Protein-2 induced osteogenic differentiation. Thus, liver dysfunction induced vitamin K deficiency can lead to decreased MGP activity and increased vascular ossification-calcification. This mechanism may also explain the association between calciphylaxis and Warfarin-a Vitamin K antagonist[7]. Total uncarboxylated MGP (t-ucMGP) could reflect arterial calcification, with lower values being associated with more widespread calcium deposits[8]. However, its level was not assessed in our patient; its measurement in future studies may be required.

The patient was eventually transferred to a regional burn unit for specialized management of the extensive calciphylaxis wounds. Shortly after, the patient passed away due to sepsis and multiorgan failure.

The pathogenesis of non-uremic calciphylaxis is not completely understood, but disruption in the calcium-phosphate-byproduct has been implicated to play a role in the disease process[4]. Abnormalities of the Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor-B(RANK, NF-κB), RANK ligand, and osteoprotegerin may be involved. Factors such as liver disease, hyperparathyroidism and corticosteroid use are known to stimulate the expression of RANK ligand and decrease osteoprotegerin, thus activating NF-κB and ultimately leading to osseous mineral loss and extraosseous mineral deposits[5].

These pathologic findings, correlated clinically, were most consistent with non-uremic calciphylaxis in the setting of alcoholic liver disease.

Management consisted of sodium thiosulfate infusions, a series of bedside nonexcisional and surgical excisional debridement (Figure 1B); in addition to broad spectrum antibiotic treatment for secondary pseudomonas aeruginosa and morganella morganii wound bacterial infections.

Figure 1 Calciphylaxis wounds in the thigh. A: Before debridement; B: After debridement.

Non-uremic calciphylaxis usually has a poor prognosis with mortality that can reach 50%, most commonly due to sepsis[4]. When calciphylaxis affects proximal areas of the body, such as the abdomen, thighs and buttocks, the mortality rates can reach up to 63%. Distal calciphylaxis, however, is associated with lower mortality, being 23% as reported in one series. The presence of associated ulceration carries a mortality rate of greater than 80%[1,5].

This lasted until they reached the avenue of orange trees, where were statues holding flaming torches, and when they got nearer to the palace they saw that it was illuminated from the roof to the ground, and music sounded softly from the courtyard

The aim of medical treatment is to reduce the serum calcium-phosphate-byproduct,which can decrease the vascular calcification. Sodium thiosulfate increases the solubility of the calcium deposits and is considered a successful therapy for uremic calciphylaxis[1,2]but our non-uremic patient did not improve when sodium thiosulfate was used alone. Cases of calciphylaxis are usually treated with analgesics, wound care, and proper nutrition. Treatments that have been studied specifically for such cases include sodium thiosulfate, bisphosphonate, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy.The use of surgical wound debridement is less established and the decision is typically individualized based on the patient characteristics and presentation[1]. No effective treatment is available for non-uremic etiologies of calciphylaxis as the pathology remains unclear[6]. Few cases of non-uremic calciphylaxis were reported with alcoholic liver disease and were treated mainly by serial debridement procedures with wound care and sodium thiosulfate infusions[6,15].

Corticosteroid use was believed to be a predisposing factor for non-uremic calciphylaxis[3], however, Biswas et al[16]reported a case with acute non-uremic calciphylaxis that improved on systemic corticosteroids. Similarly, Elamin et al[17]described another case of calcifying panniculitis that was treated with a 10 d course of oral prednisone resulting in complete healing.

An increasing number of cases of calciphylaxis have been reported in the setting of alcoholic liver disease. The treatment of choice for those patients is still unknown.There is a gap in literature about the role of extensive debridement of the calciphylaxis wounds and whether it can lead to improvement of the outcomes or cause more complications such as sepsis. At this time, further research and interventional studies need to be done to better understand the mechanism of calciphylaxis in those patients, which can help us develop a more effective treatment regimen.

CONCLUSION

Figure 2 Dermal vascular occlusion and calcium deposition within the walls of large veins and the surrounding adipose tissue.

An increasing number of cases of calciphylaxis in the setting of liver failure have recently been reported, but no primary treatment option has been discovered.Surgical debridement and sodium thiosulfate were utilized in this patient, but success was unable to be evaluated as the patient passed from complications before healing could occur. Future studies should expand upon and investigate other therapeutic options for management of non-uremic calciphylaxis in the setting of liver failure.

World Journal of Hepatology2019年1期

World Journal of Hepatology2019年1期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-cirrhotic liver: A comprehensive review

- Treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis in children

- Hepatitis in slaughterhouse workers

- Serum biomarkers and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation

- Persistent risk for new, subsequent new and recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma despite successful anti-hepatitis B virus therapy and tumor ablation: The need for hepatitis B virus cure

- Temporal trends of cirrhosis associated conditions