超常规:荷兰建筑的回归

柯尔斯顿·汉尼玛/Kirsten Hannema

戴安娜·贝福德 荷译英/Translated from Dutch by Dianna Beaufort

黄华青 英译中/Translated from English by HUANG Huaqing

这是荷兰建筑吗?瑞士建筑杂志《Modulør》的主编马科·索耶在2017年“立面技艺:重塑、激活、重释”论坛上的荷兰建筑展演后大为吃惊地发出疑问。本次论坛是由列支敦士登大学与阿姆斯特丹建筑学院、麦金托什建筑学院联合主办的。

原本他期待看到的是激进的概念,或是具有狂野形式、看不到细节的标志性建筑,或是打破常规的设计——仿佛嘶喊着雷姆·库哈斯那句著名宣言“去他的文脉”。毕竟,这才是让库哈斯的OMA、MVRDV、UNStudio、Mecanoo等荷兰建筑事务所在1990年代受到世界瞩目的原因。这一场“超级荷兰运动”——如巴特·鲁兹玛在其著作(《超级荷兰》,2000)中所定义的那样,让荷兰成为建筑界的“麦加”。

然而,这次呈现在索耶眼前的却是砖砌公寓建筑和双坡屋顶的联排住宅、1:1比例模型、手绘平面、对地域建筑传统的大量隐喻。其中,汉斯·范·德海登的作品尤其让索耶瞩目:这位建筑师的细节设计之一是一个装饰性排水口,与预制混凝土供应商合作完成,是为满足荷兰建筑业的过量降水控制规范。这个细节平常而又独具匠心,令索耶深受吸引。

1 全砖住宅楼“皮拉乌斯” /Piraeus building(摄影/Photo:Schwendinger&Büttner)

2 《Igloo》杂志封面,蒂尔堡的皮乌沙文海港亭,公民建筑事务所设计/Igloo magazine with cover pavilion by Civic architects(图片来源/Source:作者提供/Provided by author)

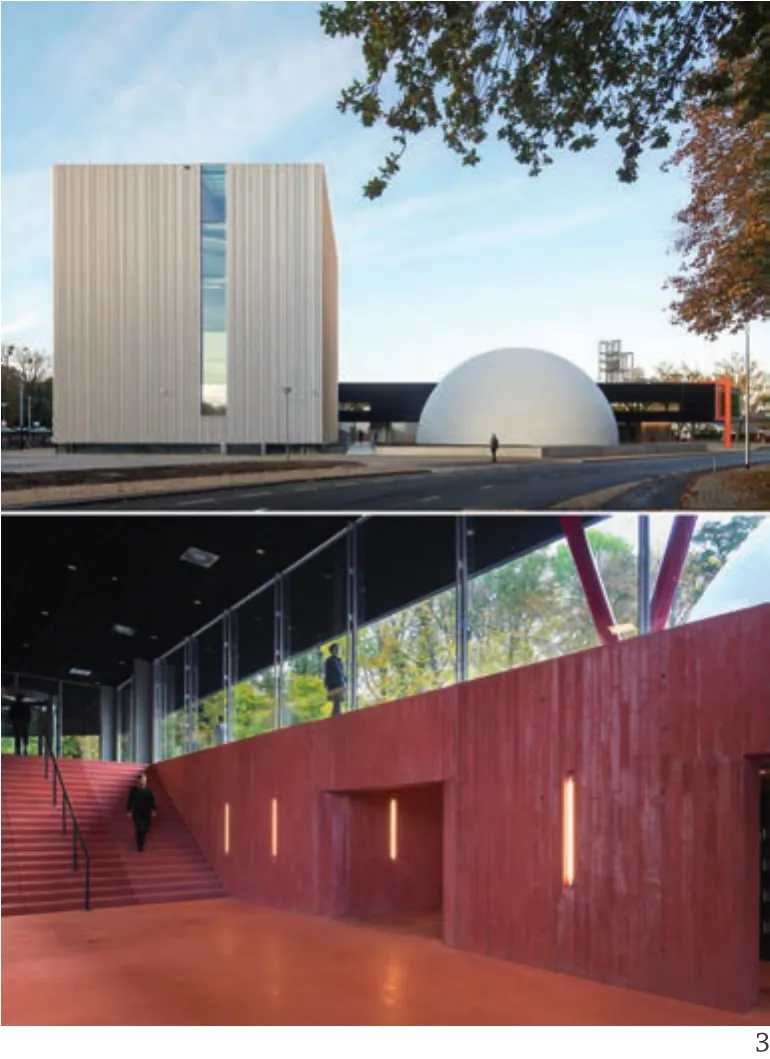

3 林堡博物馆,Shift 建筑及城市主义事务所设计,2011/Museumplein in Limburg, Shift architecture urbanism, 2011(摄影/Photo: René de Wit)

4 非奇观建筑文章/Unspectacular Architecture article(图片来源/Source:作者提供/Provided by author)

新荷兰

展览结束后,索耶与汉斯·凡·德海登的闲聊再次让他惊讶,后者告诉他,如今在荷兰有很多像他这样的建筑师:马克·德博思,雅克·德布劳威尔,杰伦·古斯特,乔·詹森及彼得·文哥德尔等。他们在令人迷醉的、以概念构思生产奇观设计的“超级荷兰”期间,依然保持着“清醒”。对他们而言,建造和对文脉的思索依然是首要问题。尽管库哈斯成了荷兰建筑的英雄,但他们的偶像却是德国建筑师汉斯·科尔霍夫——他和克里斯蒂安·拉普合作设计了阿姆斯特丹轰动一时的全砖住宅楼“皮拉乌斯”(1994,图1)。为了理解这栋建筑对其实践产生的深远影响,他们甚至为此写了一本书——《后“皮拉乌斯”》(2017)。

索耶随即决定,在《Modulør》杂志上为这7家建筑事务所的作品出版一期名为“新荷兰”的专刊,副标题为“关注文脉”。索耶对这种与众不同的荷兰建筑的欣赏并非个例。在此前几个月,罗马尼亚杂志《igloo》刚刚出版一期当代荷兰建筑专刊(2018年4/5期,图2),封面照片是年轻的公民建筑事务所的作品:蒂尔堡的皮乌沙文海港亭。这是一座粗壮的钢结构建筑,形态灵感来自港口的旧船和老桥,建筑底层是餐厅,屋顶上设置了公共观景平台。杂志还刊登了鹿特丹事务所Shift 建筑及城市主义事务所设计的林堡博物馆广场(图3),以及艺术家兼设计师弗朗克·哈弗曼斯设计的建筑装置。然而,“超级荷兰”的作品却无迹可寻。

如今,我受邀撰写这篇文章,向国际读者阐释过去几年荷兰建筑界发生的一切——很显然,我的任务并不是报道Mecanoo或MVRDV在鹿特丹建成的又一座奇观式博物馆。可以说,荷兰建筑师正在用一种全新的建筑重新在国际舞台上占有一席之地,这种建筑可谓“异常的常规”。这是如何发生的?

非奇观建筑

是经济原因?错!看起来,将过去10年的建筑界动态归咎于2008年金融危机似乎是合乎逻辑的——随着美国投行雷曼兄弟的巨幅次贷亏损,引发全球经济疲软,荷兰建筑业也随之陷入衰颓,这才慢慢催生了“新荷兰”建筑师。然而,事实并非如此简单。诚然,经济衰退的影响不可忽略。商业资本和政府的委托——那些曾驱动“超级荷兰”的金融引擎——逐步枯竭。居住和办公市场皆瓦解。40%的建筑师失业。“荷兰的建设工作已经完成,”前荷兰政府总建筑师弗里茨·范·东恩在2013年评论不计其数的闲置办公楼和商业建筑时如此断言。显然,到了需要改变的时候。

然而,早在经济衰退之前,在《A10》杂志刊登的一篇关于欧洲新建筑的文章(2007年4/5期,图4)中,建筑评论家汉斯·易卜林斯就观察到“超级荷兰运动”已日薄西山,被一种他归为“非奇观”的新风潮所取代。这篇文章的插图都是日常化的砖建筑,设计得如同普通住宅一样,但又极为关注细部和精准度。这些建筑大多出自索耶从汉斯·凡·德海登那里听闻的建筑师之手,这群建筑师已长期生存于那些“超级荷兰运动”的实验主义同行以及他们的建筑所集聚的极大媒体曝光度之下。“然而今天,这场建筑派对的喧嚣已逐步停歇,有更多人开始关注这种新的实践道路及其代表人。” 易卜林斯如此写道。

Is this Dutch architecture? Marko Sauer, editorin-chief of the Swiss architecture magazineModulør,was flabbergasted during the Dutch presentation at the 2017 symposium Crafting the Facade: Reuse,Reactivate, Reinvent, which was hosted by the University of Liechtenstein in collaboration with the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture and the Mackintosh School of Architecture.

He had expected radical concepts, iconic buildings with wild shapes and invisible detailing, mouldbreaking designs that screamed "fuck the context",to use the famous phrase by Rem Koolhaas. This was,after all, what brought Dutch architectural firms like Koolhaas' OMA, MVRDV, UNStudio and Mecanoo to the attention of the world in the 1990s – the Super Dutch movement, as Bart Lootsma coined it in his book (Super Dutch, 2000), and which positioned the Netherlands as a Mecca of architecture.

What he saw instead were brick residential buildings and gabled roofs on terraced houses, 1:1 scale models, hand-drawn plans and a whole slew of references to local architectural traditions. Hans van der Heijden's contribution in particular caught his eye: one of the architect's details was an ornamental rainwater spout, made in collaboration with a prefab concrete supplier and designed to meet Dutch building regulations for excess run-off. The detail was both prosaic and distinctive; Sauer found it fascinating.

New Dutch

After the presentation he chatted with Van der Heijden who surprised him again by telling him that there were more architects like him in the Netherlands: Mark de Bokx, Jacq. de Brouwer, Jeroen Geurst, Jo Janssen and Jan Peter Wingender. They stayed "sober" during the intoxicating Super Dutch years with its spectacular designs based on conceptual thinking. For them, construction and contextual thinking remained paramount. And while Koolhaas became the hero of Dutch architecture, they admired German architect Hans Kollhoff who, along with Christian Rapp, built – all in brick – the sensational residential complex Piraeus in Amsterdam (1994,Fig. 1). In order to understand the influence this building had on their own practice, they even wrote a book:Post Piraeus(2017).

Sauer decided to devote an issue ofModulørto what he called "The New Dutch", featuring the work of seven architectural firms, and giving it the subtitle: "Mind the Context". Sauer's admiration for a different kind of Dutch architecture was not unique. A few months prior, the Romanian magazineigloohad published an issue on contemporary Dutch architecture. On its cover was the Piushaven Harbour Pavilion in Tilburg by the young achitectural firm Civic Architects (Fig. 2): a robust steel construction inspired by the old ships and bridges in the harbour, with a roof-top public viewing platform over a restaurant. The magazine also showed the Museumplein Limburg by the Rotterdam-based firm Shift architecture urbanism(Fig. 3) and the architectural installations by artist/designer Frank Havermans. Super Dutch was nowhere to be found.

And now I have been asked to write this article, for an international audience, on what's been happening in the field of architecture in the Netherlands over the last few years – with the explicit request not to cover the latest library design by Mecanoo or MVRDV's spectacular Museum Depot in Rotterdam. That says something: Dutch architects are reconquering their position on the international stage with a new kind of architecture, a kind that could be described as"exceptionally normal". How did this happen?

Unspectacular architecture

It's the economy, stupid! It seems logical to ascribe the developments of the last decade to the global economic malaise sparked by the 2008 crisis that saw massive losses on mortgages and real estate by the American financial firm Lehman Brothers, and that plunged the Dutch architectural sector into a deep recession – and consequently gave birth to New Dutch architects. But it's not that simple. Certainly, the recession had a huge impact.Commissions from commercial businesses and the government – the financial motors that drove Super Dutch – dried up. The residential and office markets collapsed. Forty percent of architects lost their jobs."Building work in the Netherlands is complete",said former Chief Government Architect Frits van Dongen in 2013, while referencing the countless empty office and retail buildings at that moment. It was clear that something had to be changed.

Yet already before the recession, in an essay inA10magazine on new European architecture (Fig. 4),architecture critic Hans Ibelings observed that Super Dutch was on its last legs and being replaced by a new trend he categorized as "unspectacular". The article was illustrated with ordinary brick buildings, designed to look like the homes they were, but with a special attention to details and precision. They were designed by the architects Sauer had heard about from Van der Heijden, a group of architects that had been building for years in the shadows of their experimental Super Dutch colleagues and the monumental media attention their buildings garnered. "But now the roar of the architectural party has died down, there is undeniably more interest in this approach, and its respresentatives", noted Ibelings.

The rise of unspectacular architecture could be seen as a "compensation" for all the "party architecture of the past decade", according to Ibelings.You could also call it a reaction to Super Dutch,just like in the fashion industry where trends play off each other: after hippy style came punk, after glamour came grunge. After spectacular architecture,"boring"became fashionable. Another possible explanation is the increase of inner city challenges following the migration to cities and Dutch policies to limit development to within existing urban areas.Unspectacular architecture does well in an urban context where a certain anonymity is appreciated,in Ibelings' analysis: "This benefits an architecture which is not a personal expression on the part of the designer and does not attempt to express the identity and individuality of the user in its exterior."

The strength of this architectural trend was,according to Ibelings, "that it tries to escape from being held hostage by the interesting, at the very least by pretending not to be all that interesting at all…Rather than taking action against boredom [these are indeed Ibelings' words], these architects take the boredom of the everyday as a starting point, in order to eproduce an architecture that recognizes and reflects it. ...This seldom produces the shock of the new – at most a shock of recognition. On the other hand, boring architecture won't start to annoy you."

“非奇观”建筑的兴盛在易卜林斯看来,可视为对所有“过去10年的建筑派对”的“补偿”。你也可以称之为对“超级荷兰”的逆反,就如时装流行趋势的相互迭代:嬉皮风之后是朋克风,艳丽风之后又是颓废风。在奇观建筑后,“无聊”成了新的时尚。另一个可能的解释是移民潮带来的内城压力激增,荷兰的政策导向是限制现有城市区域内部的开发项目。非奇观建筑在密集城市环境中融入得当,其一定程度的匿名性受到赞赏。易卜林斯分析认为,“这种环境有利于这样一种建筑,它既非设计者的个人风格表达,亦未试图彰显内部使用者的身份或个体性。”

易卜林斯认为,这一建筑流派的力量在于,“它试图逃脱趣味的操控,至少假装得不那么有趣……他们并非倚仗无聊本身,而是将日常的无聊作为起点,以生产一种认可并反映日常性的建筑……这很少会导致新事物带来的震惊——至多是对认可日常的震惊。换句话说,无聊的建筑不会令你恼怒。”

5 居住项目丘吉尔公园,莱顿,汉斯·凡·德海登建筑事务所设计/Housing project Churchill park, Leiden, Hans van der Heijden Architect Contemporary Brick Architecture, Churchill park(图片来源/Source:作者提供/Provided by author)

6 北荷兰档案馆阅览大厅,哈佩尔-科尼利斯-韦尔霍芬建筑事务所设计,2015/Study Hall North Holland Archives,Happel Cornelisse Verhoeven Architecten, 2015(摄影/Photo:Karin Borghouts)

重新导向文脉

阿姆斯特丹Winhov事务所的建筑师彼得·文哥德尔有另一种说法(在《Modulør》杂志中发表):“对我们而言,好建筑就是更持久的建筑。它迫使你反复思考,如何将建筑适宜地嵌入它所处的文脉:如何处理场所精神、形态学关系,新建筑将如何影响场地。”当然,彼得·文哥德尔认为新建筑始终会是空间问题的“偶然性”解决方式。他认为自己最重要的使命是“探索项目潜藏的根基——如欧洲城市文脉、建筑学传统。”因此,Winhov事务所一直致力于建筑教育和普及,例如他们的网络出版物《本地英雄》,分享了他们对那些个人化英雄的痴迷——或许有些晦涩——如乔凡尼·慕齐奥、乔斯·贝多、费尔南德·普永。

材料作为概念

“后皮拉乌斯”学派成员的共识之一,是他们试图“在建筑学内部寻求合法性”,如彼得·文哥德尔所言。“概念”是“超级荷兰”的法宝,建造只能居于次席。这可能会导致某种尴尬的境遇,例如UNStudio于1996年设计的阿纳姆火车站,采用数字技术设计的一个将所有交通流线整合的“全套解决方案”,却找不到一个施工商能够建造那龙卷风形状的车站大厅。直到20年后,才找到唯一一家造船厂愿意接下这个任务。

文哥德尔的策略恰恰相反:材料是发展概念和建筑构思的起始点。作为阿姆斯特丹建筑学院的讲师(2010-2013),他负责了一项国际出版项目:《一种严苛的材料:当代砖建筑构造》(图5)。学生需要探索砖材料的可能性,并根据他们的发现做设计。Winhov事务所采取相同的方式。根据这种逻辑,他们为埃因霍温理工大学学生公寓设计了预制混凝土立面。这座校园中充斥着由精致线条框束的玻璃幕墙,故而他们希望设计一个具有浮雕感的立面,而极短的建造工期意味着预制混凝土成为一个恰当的选择。在混凝土工厂看到抛光机后,他们决定用水泥和大理石来塑造立面上的“窗棂”。大理石抛光后从立面上凸显出来,赋予混凝土独特的光泽(本刊p66)。

编织的一代

自从易卜林斯将“非奇观建筑”视为一种风潮,不断有更多年轻拥趸加入这个对文脉、传统及建造感兴趣的事务所群体:蒙纳多、科思-泰兰斯、哈佩尔-科尼利斯-韦尔霍芬、马基林·凡·艾格、莉莉斯·龙纳·凡·洪多珂、唐娜·凡·米丽根·贝尔克、安·黛兴、简·瑙塔、阿尔德·德弗里斯他们被策展人马里乌斯·古特维尔德和杨特·恩格尔斯称作“编织的一代”——这个定义出现在后者关于低地国家未来建筑的策展“Maatwerk/定制:佛兰德斯与荷兰的定制建筑(2016)”之中,作为法兰克福德意志建筑博物馆25周年回顾展的一部分。古特维尔德说,他们是“为超级荷兰收拾残局”的一代;换言之,这一代人不得不将1990年代至21世纪初建造的“标志性”建筑——往往拥有宇宙飞船式的造型——编织到城市肌理中,以建立某种统一性。

这样的空间难题恰恰激发起鹿特丹事务所哈佩尔-科尼利斯-韦尔霍芬的工作热情,他们也擅长于此。他们的成名作是哈勒姆的北荷兰档案馆(图6,本刊p84)翻修工程,将围绕庭院布置的3座建筑融为一体,重新塑造了某种平衡。经济萧条对他们影响不大,因为他们将精力转移至佛兰德斯地区——这完全符合他们对建筑异文化的兴趣。在那里,他们建成了一些住宅项目、一所学校和一座消防站。他们即将在2019年完成一个备受瞩目的项目——莱顿布料大厅市立博物馆修复。

另一位冉冉上升的“编织新星”是阿德·德弗里斯,他在2016年完成的处女作是为一户农民建造的乡村住宅,这家人正准备在荷兰东部置办一座新房产。建筑师与业主及当地工匠一起参与建造,使用了从当地废旧房屋中回收的本地橡木和石材。他让房屋的方向与种满树的河岸平行,用两堵长墙标识出车道的位置。在石基础的上方,建筑师放置了一个盒子,拥有巨大的窗户,以欣赏四周田野和树林的风景(本刊p42)。

阿德·德弗里斯不断用更高水平的项目延续着处女作的成功。他与唐娜·凡·米丽根·贝尔克合作,赢得了乌得勒支和格罗宁根的两项文化建筑委托,即将在2019年开始建造。

建筑2.0

尽管易卜林斯早在2007年就预示到,在“超级荷兰”的浪潮后,“无聊”的文脉建筑会获得更多市场;但荷兰建筑博物馆(NAi,2013年并入新博物馆)的馆长奥雷·布曼试图探索一个更激进的全新语境。他对于建筑师不断减弱的话语权感到担忧。“远比天赋或才华更为强势的多方力量正在介入建筑师的工作——金融模型、股权结构、全球化、新媒体、司法化、专业化……不胜枚举。”为寻求解决方案,他在2007年底召集了一次论坛:“建筑2.0——建筑的宿命”。他请来成功的“超级荷兰”建筑师——包括法兰馨·侯班、本·范·贝克尔、维尼·马斯、维尔·阿雷兹、雷姆·库哈斯、威廉·扬·钮特灵,分享他们对建筑未来的愿景。钮特灵说,建筑师应该少花时间扮演天才儿童、科学家或记者,而应专注于设计“好”建筑。但这并非成功的秘方,在一年后的信贷危机中便可知晓。

建筑作为必需品

住宅项目都被取消。投机商建造的新办公楼依然空空如也。一些在几年前尚野心勃勃的重大项目,必须接受重新评估。阿姆斯特丹南阿克西斯商务区的交响乐办公大厦(Architekten Cie设计)成了臭名昭著的建造诈骗案的缩影。银行家迪克·舒宁加在奥普梅尔的艺术博物馆项目(Herman Zeinstra设计)成了深度堕落的银行体系的象征。舒宁加破产后不得不变卖他的艺术藏品;博物馆至今空空如也。随之提出的问题就是:谁还需要建筑?

A reorientation towards context

Architect Jan Peter Wingender of the Amsterdambased Office Winhov describes it differently (in the Modulør article): "For us good architecture is about making buildings that last for a very long time. It forces you to think very carefully about the way a project is placed within its context: how you deal with the genius loci, the morphologic constellation, and how an addition will influence the site." Of course,a project will always be a "coincidental" solution to a spatial problem, thinks Wingender. He considers it his most important task "to explore the layer underneath the projects: the context of the European city, the tradition of our discipline". This is why Office Winhov is also involved in architectural education and awareness, which includes their online publication of Local Heroes where they share their fascination with personal – if somewhat obscure – heroes like Giovanni Muzio, Jos Bedaux and Fernand Pouillon.

Material becomes concept

Members of the post-Piraeus group are united by the fact that they "seek legitimacy within the discipline of architecture itself", says Wingender.It was the Concept that trumped all else for Super Dutch, putting the construction in second place.This could lead to some tricky situations, as was the case for Arnhem's train station by UNStudio,designed in 1996 with computer technology as a"total package" response to all the traffic routes that needed to be integrated. Not a contractor was to be found that would take on the tornado-shaped station concourse. In the end – 20 years later – a shipbuilder was the only one for the job.

Wingender works in reverse: the material is the starting point for developing the concept and the architectural thinking. As lecturer at the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture (2010-2013),he led the international project and publication:An Exacting Material: Tectonics in Contemporary Brick Architecture(Fig. 5). Students were required to play around with bricks and then design something based on what they discovered. Office Winhov uses the same approach. This is how they came to a prefabricated concrete facade for the student housing at the Eindhoven University of Technology. Buildings around campus had curtain walls with refined framing lines, and this inspired the idea of a facade with relief, while the short timeframe available for construction meant that prefab concrete was a good option. When they saw the polishing machine at the concrete factory, they decided to make "mullions" out of cement and marble for the facade. Polishing the surface brings out the marble and gives the concrete a specific sheen(Page 66).

A weaving generation

Since Ibelings identified "unspectacular architecture" as a trend, the number of architectural firms interested in context, tradition and construction has grown with new young advocates: Monadnock,Korthtielens, Happel Cornelisse Verhoeven, Marjolein van Eig, Lilith Ronner Van Hooijdonk, Donna van Milligen Bielke, Anne Dessing, Jan Nauta, Ard de Vries. They have been called a "weaving generation"by curators Marius Grootveld and Jantje Engels, in their contribution on the future of architecture in the Low Countries as part of the 25-year retrospective exhibition "Maatwerk: Custom Made Architecture from Flanders and the Netherlands" (2016) in the Deutsches Architekturmuseum in Frankfurt. They are the ones to "clean up the mess left by the Super Dutch party", says Grootveld, or in other words, the new generation will have to weave the "iconic" buildings of the 1990s-2000s – often structures like spaceships –into the urban fabric of cities to create some unity.

These spatial puzzles are exactly the kind of work that fires up the Rotterdam-based firm Happel Cornelisse Verhoeven – and they excel at them. They made a name for themselves with their North Holland Archive renovation in Haarlem, where a new balance was achieved in bringing together three buildings clustered around a courtyard (Fig. 6, page 84). The recession barely touched them as they turned their focus to Flanders – entirely in line with their interest in building cultures different from their own. Here they realized residential projects, a school and a fire station.They are set to complete their prestigious renovation of the Museum De Lakenhal in Leiden in 2019.

Another rising "weaver" is Ard de Vries, who debuted in 2016 with a country house for a family of farmers who were establishing a new estate in the east of the Netherlands. Together with the client and local craftsmen, and using local oak and stones retrieved from a locally demolished house, he positioned the house parallel to wooded banks and erected two long walls that serve as the driveway.On top of the stone foundations he placed a box with enormous windows looking out over the surrounding fields and woods(Page 42).

De Vries has managed to follow up his successful debut with more worthy projects. In collaboration with Donna van Milligen Bielke he won awards for two cultural buildings in Utrecht and Groningen, which are to be built next year.

Architecture 2.0

While Ibelings already saw in 2007 that after the Super Dutch bash there was new space for "boring"contextual architecture, the former director of the Netherlands Architecture Institute(NAi, merged into The New Institute in 2013)Ole Bouman was wanting to explore a radical new discourse. He was concerned about the increasingly weakened position of architects. "Various forces,much stronger than any talent or genius can combat, are working their way into the scope of an architect's work. Financial models, ownership structures, globalization, new media, judicialization,specialization… you name it." In search of solutions he organized a symposium in late 2007:Architecture 2.0 – The Destiny of Architecture. He asked successful Super Dutch architects – Francine Houben, Ben van Berkel, Winy Maas, Wiel Arets,Rem Koolhaas, Willem Jan Neutelings – to come and share their vision for the future of architecture.Neutelings argued that architects should spend less time trying to be whizzkids, scientists and journalists and just focus on designing "good"buildings. But this is no recipe for success, as became clear a year later with the credit crunch.

Architecture as necessity

Residential projects were cancelled. New offices,built on speculation, remained empty. Prestigious projects that only a few years earlier were presented with great aplomb, were having to be reassessed. The high-rise offices of Symphony (Architekten Cie) in Amsterdam's business district Zuidas turned into a symbol of scandalous construction fraud. Banker Dirk Scheringa's art museum in Opmeer by architect Herman Zeinstra became the symbol of a deeply rotten banking system. Scheringa went bankrupt and had to sell his art collection; the museum is still empty. It popped the question: who needs architecture?

Bouman wanted to give renewed legitimacy to the discipline by making connections with big social issues like food and energy supplies. So in 2010 he launched the programme "Architecture as Necessity",with a travelling exhibition and publication that presented the work of 25, mostly young, architectural firms. Studio Marco Vermeulen showed his design for "water squares" in Rotterdam that could collect the excessive rainfall anticipated by climate change:public squares as water basins that allowed the water to be slowly absorbed by the ground or directed to drainage systems. RAAAF(Fig. 7), consisting of brothers Ronald and Erik Rietveld, submitted"Generating Dunescapes", a design that makes use of the excess heat generated by the blast furnaces of IJmuiden, turning it into a resource for a complex of thermal baths. By Superuse Studios, pioneers in circular building strategies, there was the playground project, using the discarded blades of wind turbines.

7 “制造沙丘景观”RAAAF事务所设计/Generating Dunescapes,RAAAF(图片来源/Source: RAAAF)

8 克雷堡公寓改造项目/Flat Kleiburg(摄影/Photo: Marcel van der Burg)

布曼希望通过与食品、能源供给等社会议题的关联性,赋予建筑学新的合法性。在2010年,他发起“建筑作为必需品”项目,包括一项巡回展及相关出版物,展示了25家建筑事务所(大部分是年轻的)的作品。马可·韦尔默朗事务所展示了他的鹿特丹“水广场”设计,这个广场能够收集气候变化可能带来的过量降水:公共广场作为蓄水池,让水慢慢被土地吸收或导入排水系统。还有罗纳德与埃里克·里特维尔德兄弟的RAAAF事务所提交的“制造沙丘景观”的设计(图7),利用艾默伊登的鼓风炉制造的多余热量,转化为一个温泉浴场的热源。还有超级利用事务所,他们是建筑热量循环利用的先驱者,其设计的游乐场项目使用了废弃的风车扇叶。

“建筑作为必需品”项目展现了一种新的建筑实践路径,通过社会介入来提升建筑价值。但是,大多数项目其实都是经济危机之前设计的。和那些“非奇观”潮流的建筑师一样,理想主义建筑师也一直存在。只不过在“超级荷兰”期间,他们被视为另类——可能还带着某种怜悯。而如今,他们却成了先锋派。

为人民的建筑

“建筑作为必需品”项目希望抛开明星建筑师以及标志性建筑项目的文化。他们雄心勃勃:新一代建筑师应该解决世界性的大问题。当然,对大多数人来说,建筑学并不是必需品(只是5%的建筑是在建筑师的引领下建造的)。建筑学只是个奢侈品。好设计又能带给人们什么?建筑如何能帮助提升日常生活品质?

为了回答这个问题,代尔夫特理工大学与赫曼·赫兹伯格(为了纪念他80周岁生日)共同组织了2012年“建筑的未来”论坛。赫兹伯格——作为荷兰结构主义最著名的代表人物之一,因其人性化尺度的建筑而闻名——在如此高龄依然希望向前看,而非向后看,因而邀请了几位年轻的、具有社会向度的建筑事务所共同谈论他们的作品。

NL建筑事务所和XVW 建筑事务所展示了他们的克雷堡公寓改造项目(图8)——这是一栋战后建造的巨型外廊式公寓,位于阿姆斯特丹的庇基莫米尔街区。这栋建筑曾是这个被彻底遗忘的、由失败的现代主义思想塑造的大型公寓楼街区的象征。几乎所有住宅楼都在1990年代被拆除,以建造全新的公寓楼和联排住宅。经济衰退意味着没有人再为拆除买单,于是克雷堡公寓楼被以1欧元的总价卖给了一群年轻的开发商。他们采取了DIY的改造方式:500套公寓楼都要由购买者自己修整入住。最大的惊喜是建筑改造执行的方式:大多数外廊式公寓在改造时,都会用油漆或贴面来装点一新,而这个项目的建筑师选择恢复克雷堡公寓极盛时期的粗野主义面貌。这个项目获得了2017年密斯·凡·德罗奖(击败了OMA的米兰普拉达基金会以及鹿特丹的提默胡斯大楼)。评委会写道,“克雷堡公寓……帮我们构想了一种新的建筑实践,回应了21世纪不断变化的家庭模式及生活方式:对现有建筑的改造以及对旧有建筑类型的复兴,与新模型的实验探讨一样是切实的、激进的。”

另一个旧建筑激活案例是DUS建筑事务所(也受赫兹伯格邀请到论坛发言)的阿尔梅勒新城哈芬街区改造规划。DUS 建筑事务所于2004年由海德薇格·海恩斯曼、汉斯·韦尔默朗和玛蒂娜·德韦德联合创立,他们的成名作是由雨伞和塑料袋搭建的快闪亭——由建筑师亲自参与建造,致力于让更多当地人加入到更宏大的建设项目中。他们暂时搬入一座即将在阿尔梅勒哈芬区改造的联排住宅,在现场分析邻里的空间品质,并观察记录当地人生活中表现出的需求。

这项改造规划中第一个实现的新型社会住房项目是科思-泰兰斯建筑事务所设计的花园洋房,一个对花园城市生活的当代诠释。为了尽量节约绿化用地——这不仅是阿尔梅勒哈芬区的城市特征,也深受当地居民的欣赏——这座建筑设计为一座由公共花园环绕的紧凑型公寓。建筑外立面裸露的混凝土结构(表面为碎石质感)支撑着宽敞的阳台,阳台上设置了储存空间和植物房。结构形式赋予这座建筑粗犷的外观,而材料质感则让它更好地融入街区周围的1970年代的建筑之中(本刊p54)。

多样的建筑景观

回顾过去10年,显然在荷兰建筑界发生了很多事,但却很难将这一切纳入一个简单的类别定义。在这个混合体中并不存在所谓“新建筑师”或“新荷兰建筑”。文脉、工匠技艺、公众参与和社会议题都是重要的建筑主题,同样不可忽略的还有建筑的可持续性、3D打印等新技术、文化内涵。“超级荷兰”依然发挥着作用。这些著名建筑师所拥有的经验和人脉意味着他们能够获得大量不会对年轻建筑师开放的重大项目。然而,这些大型事务所的作品中同样出现了微妙的转型,从设计建筑单体转向设计更广义的城市结构,如OMA像素化的鹿特丹提默胡斯大楼(库哈斯称它为一个“反标志性”)。从痴迷于概念到对建造感兴趣的转变,亦可见于UNStudio和年轻事务所RAP工作室最近的一项合作项目,他们将参数化设计与计算机驱动的机械臂相结合。此外,还可看到从渴求原创性到延续前人设计的转变——在MVRDV的维尼·马斯领衔的“问题工厂”2017年出版的著作《复制粘贴》中,就阐释了如何引用建筑史范例。

这种多样性对于鹿特丹事务所Shift 建筑及城市主义而言非常熟悉。创始人哈尔姆·蒂莫曼,奥阿尼·拉迪斯和塞吉·凡·比吉斯特维尔德都曾在“超级荷兰”的事务所中工作,在那里他们学会了如何利用概念来思考和沟通。在新的事务所中,他们希望探索一条不同的路径,关注空间体验、当地文脉和建筑的建造工艺。当然,他们依然借用设计概念来做研究——例如城市农村、运动设施和微型住宅。当下的状态,正是他们出发探索自己的建筑学的起点,现存的空间逐步会经过改造焕然一新,这也就是事务所名字“转变”的内涵。

尽管大多数“后皮拉乌斯”学派成员倾向于砖作为材料,但Shift事务所仍欣然采用混凝土、钢和石材,而无视文脉展现的需求。他们的处女作是2011年蒂尔堡大学校园中的教师俱乐部:一座位于林间空地上的多功能建筑。它如同校园中的石材建筑——于1950年代由建筑师乔斯·贝多设计——与现代主义玻璃住宅的混合体:一块内部掏空的巨石,细节精准至最后一颗螺丝(本刊p60)。林堡的博物馆广场则完全不同,如同由强势的几何体组成的城市集群(使人想起OMA的早期作品),建筑结构的外显是为了契合当地的工业环境。

或许很难将Shift事务所归类,他们的作品没有清晰的标签。他们自称为“杂食动物”,称自己的建筑为“变色龙”。你或可将它当作弱点,亦可视为他们的长处。 当下的荷兰建筑亦是如此。□

Architecture as Necessity was presenting a new sort of architecture focused on the added value of social engagement, but many of the projects were conceived before the economic crash. And just like the architects behind the unspectacular trend,idealistic architects have been around since time immemorial. It's just that they were considered –with some pity – alternative types on the Dutch scene. Now, however, they are frontrunners.

Building for people

"Architecture as Necessity" wanted to do away with the stararchitect and culture of iconic architectural projects. Ambitions were high: new architects would solve the world's big problems. Of course, for most people architecture isn't a necessity(only 5% of buildings are built under the guidance of an architect) [95% of the buildings are realised without an architect], it's merely a luxury. What can good design offer them? How can buildings contribute to a higher quality of everyday life?

In an attempt to answer this question, the Delft University of Technology and Herman Hertzberger(in honour of his 80th birthday) organised the 2012 symposium "The Future of Architecture".Hertzberger – one of the best-known representatives of Dutch Structuralism and renowned for the human scale of his buildings – wanted to look ahead, in his old age, rather than look back, and thus invited several young, socially-engaged architectural firms to talk about their work.

NL Architects and XVW Architecten presented their renovation of Kleiburg (Fig. 8), an enormous, run-down gallery flat in the post-war neighbourhood of Bijlmermeer in Amsterdam. The flat had become symbolic of the utter neglect of this area of residential tower blocks and the failure of Modernism that conceived them. Nearly all of the flats were demolished in the 1990s to make room for new flats and terraced houses. The recession meant that there was no more money for demolition and Kleiburg was sold for a token sum of 1 euro to a group of young project developers. They adopted a do-it-yourself approach: the 500 apartments were to be fixed up by the buyers themselves. The big surprise was the architecture implemented: while gallery-access flats were usually spruced up with a lick of paint and new cladding, the architects decided to restore the brutalism of Kleiburg in all its former glory. The project won the Mies van der Rohe Award in 2017 (beating out OMA with its Fondazione Prada in Milan and its Timmerhuis in Rotterdam).The jury wrote: "Kleiburg …helps us imagine a new kind of architectural project, which responds to changing household patterns and lifestyles in the twenty-first century: the transformation of an existing building and a revitalisation of typologies of the past, that are as relevant and radical as experimenting with new, untested models".

Another example of revitalisation was a plan by DUS Architects (also invited by Hertzberger to speak at the symposium) for the transformation of the Haven neighbourhood in new town Almere.DUS, established in 2004 by Hedwig Heinsman,Hans Vermeulen and Martine de Wit, had gained recognition with their pop-up pavilions made of umbrellas and grocery bags, built by themselves as part of an effort to engage locals in the bigger projects. They temporarily moved into a terraced house that was going to be renovated in Almere Haven, and from there they analysed the spatial quality of the neighbourhood and took stock of the needs expressed by people living there.

The first new affordable housing project realised in their master plan was Het Tuinhuis (The Garden House) by Korthtielens, a contemporary interpretation of life in a garden city. In order to save as much as possible of the green space so characteristic of Almere Haven – and much appreciated by its residents –it is a compact apartment building surrounded by a communal garden. The building's exterior is of concrete (with a gravel finish) that carries the weight of all the spacious balconies that include storage spaces and plant containers. The final structure is what gives the building its strong face,and its materials allow it to integrate well with neighbouring 1970s architecture(Page 54).

Diverse architectural landscape

Looking back over the last ten years, it's clear that not only a lot has happened in the Netherlands, but also it's not easy to categorise all these developments into a single definition. There is no New Architect or New Dutch Architecture rising from the mix. Context, craftsmanship, public engagement and social agendas are important themes, as are sustainability, new technologies like 3D printing, and cultural significance in architecture. Super Dutch still plays a role. The experience and references of these established architects means they get a lot of major projects that are simply not open to young architects. And yet, there is a slight shift happening in the work of these big firms, from designing architectural objects to design for broader urban structures. For example:OMA's pixellated Timmerhuis Rotterdam (described by Koolhaas as an anti-icon). The move from conceptual interests to interest in the construction can also be seen in the new collaboration between UNStudio and the young firm of Studio RAP,in their combination of parametric design with computer-driven robots. And there's the shift from striving for originality to building upon what went before, as illustrated in the bookCopy Pastepublished last year by "The Why Factory", headed by Winy Maas of MVRDV, covering how to employ references from architectural history.

This diversity is very familiar to the Rotterdam firm Shift Architecture+Urbanism. Founders Harm Timmermans, Oana Rades and Thijs van Bijsterveldt were trained at Super Dutch firms, where they learned how to think and communicate in terms of concepts. They wanted to go in a different direction with their new firm, focusing on spatial experiences,local context and the craft of building itself,though they also still do research through design concepts – like urban farming, sports facilities and microhousing. The present state is the point of departure for developing their architecture, so that the existing space is gradually transformed into something new; hence the name Shift.

While the post-Piraeus group preferred brick,Shift will work just as gladly with concrete, steel and stone – whatever the context calls for. They debuted in 2011 with their Faculty Club on Tilburg University's campus, a multifunctional pavilion situated in an open spot in the woods. It's a cross between the stone buildings on campus, designed in the 1950s by architect Jos Bedaux, and a Modernist glass house:an excavated stone monolith, detailed very precisely,down to the last screw(Page 60). Museumplein in Limburg is a totally different kind of building as it is an urban composition of strong geometric volumes(reminiscent of OMA's early work) and an injection of structure for the industrial environment here.

It is difficult to categorise Shift A+U and as a firm, they don't have a clear signature in their work.They describe themselves as "omnivores" and their architecture as chameleonic. You could see this as a weakness or as their strength. The same is true for current Dutch architecture.□