从淡巴菰到返魂香

——读《中国烟草史》有感暨浅谈19世纪末前烟草在中国的流变史

◇ 文 |

爷爷是个老烟民。我自小和他生活过一些岁月。

在那些随着时间沉淀而模糊的记忆中,少许的几个片段却愈发清晰起来。其中,就有我给爷爷装烟点烟的镜头。

镜头中那烟叶是黄褐色,皱皱的缩成枯长的躯干,散发出莫名的香气。爷爷叫它“叶子烟”。当爷爷讲话讲得有点多了,或是想休息一下的时候,他就用自己布满皱纹的手掌把一片叶子搓成圆棒状长长短短的一截,我负责把这一截插进那些或大或小或长或短的烟嘴里,用煤油打火机点燃。

而后,爷爷靠躺在被汗水染黄的躺椅上,吧嗒吧嗒的声音给那烟卷的一明一暗打着拍子。

大概是被那股熏人的莫名香气迷住了,我打小就以为,这土黄土黄的东西就是咱自家土生土长的。

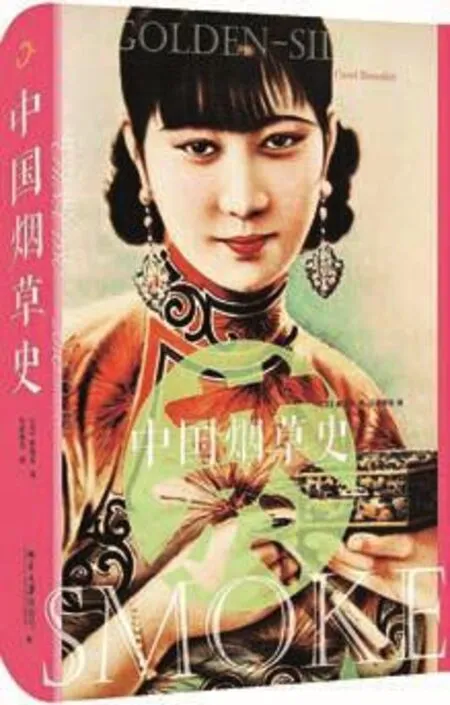

这个印象持续了大概有30来年。中间间或听说过,烟草其实是舶来品,原产地是美洲。可也不曾怎么留意过。直到前几天,看了一本叫《中国烟草史》的书。

My grandpa is a habitual smoker. I have lived with him for some years since I was a child.

In those memories that blur over time, a few fragments become clearer.Among them, there was the scene of me loading tobacco and lighting it for grandpa.

I remembered, the tobacco leaves were tan, wrinkled and shrunk into withered and long trunk, giving off an inexplicable aroma. Grandpa called it “Yeziyan” (tobacco of leaves). When Grandpa had talked a little more or wanted to have a rest, he rubbed a leaf into a long or short, round stick with his wrinkled palm. I would insert this into those big or small, long or short cigarette holders and lighting it with kerosene lighters.

Then, grandpa laid on the couch dyed yellow with sweat, smoked the pipe and smacked his lips with rhythmed flickering of the lit pipe.

Probably I was fascinated by the strange fumigating aroma, I had thought since I was young that this yellowish thing was our indigenous produce.

This impression had lasted for about 30 years.From time to time, I have heard that tobacco is actually imported and its origin is America. But I never really noticed. Until a few days ago, I read a book calledThe History of Tobacco in China.

烟草,真真切切是舶来品,的的确确来自美洲。

读着皇甫秋实的译文我才发觉,爷爷抽的叶子烟,和烟草进入中国初期的形态是很相近的。在书中,烟草在1550年之后的某个清晨,乘着西班牙人的大船从菲律宾吕宋岛等地抵达福建的泉州漳州一带。它们藏身于那些西班牙或是菲律宾裔的水手挂在胸前或者腰间的烟袋里,长着和我小时候看到的差不多的样子,散发着和我小时候闻到的差不多的味道。

在书中,班凯乐介绍了四条“烟草入华路线图”,分别是早至16世纪中期的菲律宾—福建泉州、漳州—广东、江浙一带的菲律宾路线;16世纪末的日本—朝鲜—东北和蒙古东部的日本朝鲜路线;16世纪末17世纪初的印度、缅甸—云南—成都—甘肃—蒙古的印度路线和欧洲(英国或荷兰)—俄罗斯—新疆—甘肃的欧洲路线。

爷爷是云阳人。这个长江边的小镇,曾经一度是湖广填四川的水路要津。爷爷本身也很可能是那场大迁徙中移民的后代。

班凯乐在讲述中国卷烟生产、消费和贸易的扩张这一部分时特地指出,移民对于烟草的种植和消费进入中国西南腹地的重要性。

Tobacco was truly imported, and it did come from America.

After reading Huangfu Qiushi’s translation, I realized that grandpa’s tobacco of leaves was very similar to the early form of tobacco into China. The book says, tobacco arrived in the regions of Zhangzhou and Quanzhou of Fujian province one morning after 1550 in a Spanish ship from Luzon Island, Philippines and other places.They were hidden in cigarette bags hung on the chest or waist by Spanish or Filipino sailors. Those bags looked similar to what I saw when I was a child and smelled similar to what I smelled when I was a child.

The book says, Carol Benedict introduced four“routes of tobacco entering China”, namely,the Philippine route of Philippine—Quanzhou and Zhangzhou of Fujian Province to Guangdong, Jiangsu and Zhejiang Provinces as early as the middle of the 16th century; the Japan-North Korea route of Japan—North Korea—Northeast China and eastern Mongolia in the late 16th century; the Indian route of India, Burma—Yunnan—Chengdu—Gansu—Mongolia, as well as the European route of Europe (UK or Holland)—Russia—Xinjiang—Gansu at the end of 16th century and early 17th century.

My grandpa is from Yunyang, a small town along the Yangtze River, which was once the water route and key post for population migration from Huguang to Sichuan. My grandpa himself may well be the offspring of immigrants during the great migration.

Carol Benedict specially pointed out the importance of immigrants to the cultivation and consumption of tobacco in the hinterland of southwest China when he talked about the expansion of China’s cigarette production, consumption and trade..

移民的脚步将烟草的种子带出福建,撒在中国华南、西南、西北等地的丘陵地带。1793年至1794年,陪同马戛尔尼出使中国的爱尼斯·安德逊在使团经过山东时曾经注意到,“中国人对这种植物的种植和制造达到很高程度。烟草种类之多亦非世界各国所能比拟。”

很快,一些质地优良、加工精细的烟草获得了卓越的口碑,继而树立起自己的品牌——“17世纪,在漳州种植的‘石码’烟草被很多人认为是世上最好的烟草。18世纪,‘石码’烟草首先被‘蒲城’烟草取代,然后被‘永定’烟草取代。”品牌的声誉带来的是丰厚的利润:道光时期,在永定加工的条丝烟的售价超过了一千贯。其他地区生产的较低档次的烟草,价值在一百至两百贯之间。

到18世纪末19世纪初,烟草已经渗透到中国各个阶层民众的日常生活之中。不仅出现了专门销售烟草的商行,在一些农村集市和偏远村庄,甚至出现了出租烟袋,使消费者可以当场吸烟的流动烟贩。

The tobacco seeds followed the immigrants’footsteps out of Fujian and spread in the hilly areas of south, southwest and northwest China. From 1793 to 1794, Ennis Anderson, who accompanied George MaCartney on his mission to China, noticed when the mission passed through Shandong, “the Chinese have grown and manufactured this plant to a fairly high level. The varieties of tobacco are not unmatched by those of other countries in the world.”

Soon, some fine quality and fine processing tobacco won excellent reputation, and then set up their own brand –“Shima” tobacco planted in Zhangzhou in the 17th century was considered by many people to be the best tobacco in the world. In the 18th century, the“Shima” tobacco was first replaced by the “Pucheng”tobacco and then by the “Yongding” tobacco. The reputation of the brand brings about great profits:during Daoguang dynasty, the price of the tobacco tow processed by Yongding was priced at more than 1,000 copper coins. The lower grade tobacco produced in other regions was worth between 100 and 200 copper coins.

By the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, tobacco had penetrated into the daily life of Chinese people of all walks of life. There were not only businesses specializing in selling tobacco, but also cigarette peddlers who rented cigarette bags and allowed consumers to smoke on the spot in some rural markets and remote villages.

《中国烟草史》是一部优秀的学术著作,获得美国历史学会2011年度费正清东亚研究奖就是一个最好的证明。不过或许是本书的目标读者是那些对于中国烟草史有一定甚至很深了解和研究的人士,像我这样对烟草知之甚少的初级读者,关于烟草最初进入中国时国人使用烟草的方式和形态,以及可以更生动直观地说明烟草中国化过程的烟草名称的流变,在书中却难以找到。

比如,关于国人最初如何使用烟草的文字,班凯乐的叙述中几乎没有。在川床邦夫的笔下,我找到了简单的两句——明末姚旅《露书》中记载“吕宋国出一草,曰淡巴菰,一名醺。以火烧一头,以一头向口,烟气从管中入喉,能令人醉,且可辟瘴气。”

这种状态,其实和烟草的发源地美洲的原住民们差不多:这种东西被当时的印第安人称作“达巴科”(Tobaco)。

The History of Tobacco in Chinais an excellent academic work, and winning the 2011 John King Fair-bank Center for East Asia Research Award of the American Historical Association is the best proof.However, perhaps the target readers of this book are those who have a certain or even deep understanding and research on Chinese tobacco history, while for junior readers like me who know little about tobacco, the way and form of tobacco used by Chinese people when tobacco first entered China, and the evolution of tobacco names that could more vividly and intuitively explain the process of tobacco localization in China, are hard to find in the book.

For example, there are few words about how the Chinese originally used tobacco in Carol Benedict’s narration. In Kunio Kawadoko’s work, I found two simple sentences--Lu Shuwritten by Yao Lv in the late Ming dynasty “Luzon kingdom produces a grass, named Danbagu, or Xun (tipsy). burning one end and putting the other end to the mouth, smoke goes into the throat from the pipe, which can make people drunk and dispel miasma.”

This description is actually similar to that of the native Americans, the birthplace of tobacco,which was called “Dabake (Tobaco)” by the Indians at that time.

一个“淡巴菰”,一个“达巴科”,这两个读音接近的词中间会不会有关系呢?在书后的注释中,班凯乐为我们揭晓了谜底——“淡巴菰”是西班牙语烟草(el tabaco)的音译。该词源于泰诺语。这种语言为大安德列斯群岛上的阿拉瓦克印第安人所使用。

果真,“淡巴菰”就是“达巴科”。

那么,“淡巴菰”是怎么变成“烟草”的呢?据川床邦夫在《中国烟草的世界》中的简单统计,烟草在中国曾经有过三十多个名字。俯瞰这些名称的流变,也可一窥这个“新奇本草”在中国的引进和本地化的过程。

最初,根据音译,烟草被叫做“淡巴菰”“淡把姑”“淡芭菰”“淡苋菰”“淡肉果”“打姆巴古”“担不归”“丹白桂”等。从后两者可明显看出,译者试图从意义和美感上来“装饰”这种越来越受欢迎的“草状物”。

另外,还有些名称在今人看来,可能一下子不大好理解。比如“烟酒”“醉仙桃”“延命草”等等。不过通过姚旅和卡萨斯的描述不难看出,烟草有令吸食者“醉”的功效,同时还有镇静、祛乏甚至消除饥饿的“神奇”。这实际上是因为烟草中尼古丁所具有的增加心脏速度和升高血压并降低食欲的功用。

除了上述三个名称,烟草还因为外形和疗效的缘故被冠以“黑老虎”“金鸡脚下红”“黑于莵”等现在看来稀奇古怪的名号。

1638年,在一本名为《食物本草》的书中,出现了“煙草”一词,7年后的1645年,“烟草”这个如今国人耳熟能详的词汇出现在《食物汇言》一书上。这是“烟草”的第一次出现。此时,烟草进入中国已经快有一百年了。从这个词的构成上就可以看出,这是对这种植物在使用时候燃烧冒烟的偏中性描述。

A “Danbagu” and a “Dabake”, how could these two words with similar pronunciations not have any connection? In the notes at the back of the book, Carol Benedict revealed the answer to the riddle, “Danbagu” is a transliteration of Spanish word for tobacco (el tabaco), which comes from the Taino language. This language is used by Arawak Indians in the Greater Antilles Islands.

Indeed, “Danbagu” is “Dabake”.

So, how did “Danbagu” become “tobacco”?According to Kunio Kawadoko’s simple statistics inThe World of Chinese Tobacco, tobacco once had more than 30 names in China. Looking at the changes of these names, we can also see the process of introducing and localizing this “novel herbal medicine”in China.

At first, according to transliteration, tobacco was called “Danbagu”, “Danmigu” “Danrou-guo”, “Damubagu”, “Danbugui”and “Danbaigui”, etc… From the latter two, it can be clearly seen that the translator tries to “decorate” this increasingly popular “grass like thing”in terms of meaning and beauty.

In addition, there were still some names that, in today’s view, may not be easily understood at once. Such as“Yanjiu (alcohol and tobacco)”, “Zuixiantao (peach that can make celestial being drunk )”, “Yanmingcao (life-prolonging grass)” and so on. However,through the description of the Yao Lv and Casas, it is not difficult to see that tobacco has the effect of making the smoker “drunk”, while it has calm effect,dispel fatigue or even the “magic” effect of mitigating sense of hunger. This is actually because nicotine in tobacco has the function of increasing heart beats,raising hypertension and reducing appetite.

In addition to the above three names, tobacco has been dubbed “Heilaohu (Black Tiger)”, “Jinjijiaoxiahong (Golden Rooster with red Feet)” and “Heiyutu (Black Rabbit)” which sound pretty weird today.

In 1638, the word “Yancao (tobacco)” appeared in a book called “Dietary Chinese Material Medica”.Seven years later in 1645, the word “Yancao (tobacco)” now familiar to Chinese people appeared in the book “Collection of Expressions for Food”. This is the first appearance of “Yancao (tobacco)”. At this time, tobacco had been into China for nearly 100 years. As can be seen from the composition of the word, this is a neutral description of the burning and smoking of this plant when it is used.

有趣的是,这两个称呼分别出现在两本对食物进行介绍的读物中,可见当时的人,对烟草的定性和分类。

此外,烟草还有“烟茶”“妖草”“南蛮草”“绿南草”等从朝鲜、日本漂洋过海而来的名字,这些名字也佐证着当初烟草入华的“朝鲜路线”。

在之后的几百年中,烟草一词或因其准确简便,利于传播而战胜了其他称呼。相较而言,我更喜欢之前和之后陆续出现在文人诗词和笔记中的一些称呼,比如姚旅在《露书》中提到的“金丝熏”,《粤志》中的“金丝草”,1661年沈穆在《本草洞诠》中的“相思草”。

在众多名称中,有一个因为传说更显神奇。《梅谷偶笔》记载,“淡巴国有公主死,弃之野,闻草香忽苏,乃共识之,即烟草也,故亦名返魂香。”异国公主,闻香返魂,神奇而浪漫。

Interestingly, the two names appeared in two books about food, showing the characterization and classification of tobacco by the people of that time, .

In addition, tobacco also has the names of“Yancha”, “Yaocao”, “Nanmancao” and“Lvnancao (Green South Grass)” imported from Korea and Japan, which also support the “Korean Route” of tobacco entering China in its early days.

In the following few hundred years, the word“tobacco” probably won over other titles because of its accuracy, simplicity and ease of dissemination.In comparison, I prefer some names that appeared in literati’s poems and notes before and after, such as Yao Lv’s “Golden Smoke” mentioned in Lu Shu,the “Golden Grass” in Yue Zhi and “Xiangsicao(acacia grass)” in Shen Mu’sFull Interpretation of Materia Medicain 1661.

Among the many names, one is more magical due to a legend.Meigu Notes Selectionrecords that “after the princess in Danbagu kingdom died, her body was abandoned in the wild, when she was waken up by the fragrant smell, and the surrounding people found out it was the fragrant grass, tobacco, which later got its name of resurrecting grass.” The exotic princess, who resurrected and was waken up to the smells of tobacco, which is really magical and romantic.