纽约故事

文:司马勤(Ken Smith) 编译:李正欣

Musical America

)每年年底的节日派对、纽约爱乐乐团春节音乐会与卡内基音乐厅演出季开幕盛会。其实,三者中选其二已经足矣。今年乐季截至目前,我仅出席了卡内基音乐厅演出季开幕晚宴。当天的盛况,与很多类似的场合相仿,基本上就是找个借口让大家在一起庆祝。在演出后,捐出巨额款项的善长仁翁共聚一堂,参加衣香鬓影的晚宴。换句话说,演出只是鸡尾酒会与晚宴的间场。

但是,要评价间场表演的话,卡内基还真算是选了一个不错的乐队。这个乐团的水平很高,但对于他们来说,演出曲目简单至极,只能算得上大众音乐会程度罢了——第一首乐曲是格什温的《古巴序曲》,最后一首是《美国人在巴黎》。两首乐曲之间是两位女高音——蕾内·弗莱明(Renée Fleming)与奥德拉·麦克唐纳(Audra Macdonald)轮流献唱(后来也有两人齐唱)。一切都令人惬意,直至她们走上台时,手持着……话筒。我把目光移至过道另一边、坐在前两排的安东尼·托马西尼(Anthony Tommasini),看看他有什么反应。

过去20多年来,这位《纽约时报》的首席音乐评论家是反对声乐扩音运动的主导者之一。那些坚守传统的人有着他们一系列的准则,而安东尼的清单上最重要的一栏,就是全面谴责音乐厅或歌剧院备有话筒。他的理由似乎很明确:无论是演出场地或剧目本身,存在的年代远比电子扩音科技的发明要早得多。当歌唱家拿着话筒时,你如何去判断他们自然原声的水准?对安东尼来说,扩音就相当于为声音“整容”。

我看得不太清楚,但安东尼好像在微笑。是他近年回心转意了吗?还是人到中年,“柔化”了本来的高标准吗?最有可能的是,他抱着“欢聚”的心情,暂时撇开苛刻的标准,直至翌日旧金山交响乐团演奏斯特拉文斯基专场的时候。

说真的,就托马西尼先生坚决抵制扩音这个观点,我并不认同。大量近年来的作品——我是指,比我要年轻的那些——它们的创作初衷已经考虑到扩音问题。自法兰克·辛纳屈(Frank Sinatra,1915~1998,美国歌手、影视演员)的时代开始,话筒早已成为我们感知声音的一个不可或缺的重要组成部分——而辛纳屈肯定要比托马西尼早出生。向话筒和电子扩音宣战,就好比在今天突然试图禁止使用电吉他一样。

但那个晚上,我觉得自己被拉到了安东尼的阵营。对于用不用话筒我不发表意见;但没有好好地利用话筒这让我十分不满。

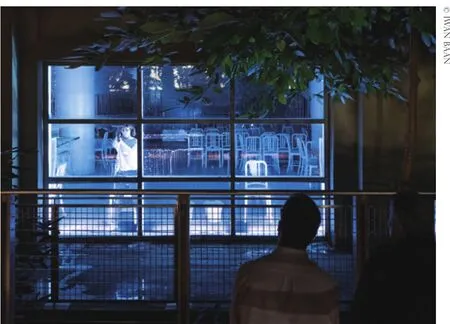

卡内基音乐厅演出季开幕演出,蕾内.弗莱明(中)与奥德拉.麦克唐纳(左)(摄影:李之中)

电吉他这个比喻其实十分严肃。尽管歌唱家从一学唱歌的时候开始,老师就喋喋不休地灌输,听众对声乐艺术的感知最为直接,钢琴或小提琴就比不上了,因为它们要依赖于作为乐器的木头“修饰美化”——但是,真实的情况却不一定是这样。任何流行歌手都明白话筒的重要性。话筒不只是为了扩大音量;它还可以改变声音的本质。歌唱家必须把话筒当成乐器,熟知所需的使用技巧。

从艺术造诣上来说,请来弗莱明与麦克唐纳当然是聪明之举。弗莱明可算是美国最负盛名的歌剧演员,麦克唐纳则也许是当今百老汇得奖最多的演员。两人都尝试过涉足彼此的专业领域。她们在台上介绍说,两人不约而同地都录制了桑德海姆《魔法黑森林》(Into the Woods

,又译《拜访森林》)里的《孩子会听到》(Children Will Listen),外加理查德·罗杰斯《南太平洋》(South Pacific

)中《你必须谨慎地受教》(You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught)的集锦歌。可惜,对于话筒,只有一位女高音懂得怎样运用。麦克唐纳驾驭这个设备犹如像挥舞自己的手臂那般自然。弗莱明则完全不理会话筒的存在——多么可爱的伎俩,这能把观众与她的距离尽量拉近。但是,如果我们去关注声线的质感与色彩——尤其是音量大小的把控——弗莱明完全忘了最基本的技巧:话筒有时候要靠近,有时候要离远。

但那仅是一个音乐季的开幕庆典演出,大家都不介意这些小失误。两晚后,乔纳斯·考夫曼(Jonas Kaufmann)从大都会歌剧院的《西部女郎》(La Fanciulla del West

)排练中请了一天假,在卡内基音乐厅罕见地举行了独唱音乐会,由圣路克乐团伴奏。曲目则是德国于两次世界大战之间、魏玛年代的舞台与电影歌曲,即“柏林的咆哮的20年代”(the Roaring Twenties of Berlin)的流行音乐。而“站”在台上、考夫曼正前方的——是个话筒。说真的,在我踏入音乐厅前,没有仔细研究过当天的曲目。我相信这绝不是例外:当晚的很多观众都是考夫曼的粉丝,在细看演唱的曲目前,只要把他的名字登出来,整场演出的门票立刻售罄。但我期待的,是这位大家公认的歌剧明星怎样利用他那强大的票房效应给观众演绎他最喜欢的歌曲——比如说,他成长期的曲子,或是演出歌剧中的名曲唱段。

乔纳斯.考夫曼在卡内基音乐厅的独唱音乐会(摄影:李之中)

我们曾经见证过其他这样的案例:多明戈演唱西班牙传统的萨苏埃拉(zarzuelas)、布莱恩·特菲尔(Bryn Terfel)演唱勒纳与洛伊(Lerner and Loewe)所写的百老汇名曲、基莉·迪·卡娜娃演唱格什温。虽然卡娜娃那张格什温的录音被诺曼·莱布雷希特(Norman Lebrecht,著名古典音乐评论家)评为史上最差20张唱片之一——但每一位歌手显然都在唱一些贴近他们内心的歌。

可是考夫曼那晚的演出令我质疑,他此前有没有听过那些歌曲,更不用说伴随这些歌曲一起成长了。让我用甜品来做个比喻吧:就像一整盘全都是奶油的点心,几乎没有脆皮,更不用说里面的饼馅了。

“我真的不需要话筒。”考夫曼对着卡内基音乐厅的观众笑着说,他要证明自己宝刀未老,嗓音还可以绕梁三日。但事实上,他确实需要话筒;只不过他不确定应该如何使用它。罗伯特·斯托尔兹(Robert Stolz)的电影主题曲“在梦里,你让我做一切”(Im Traum hast du mir alles erlaubt)来自一个话筒驾驭的音响世界;莱哈尔为舞台创作的《风流寡妇》与《帕格尼尼》选段当然讲究传统歌剧的火力。可惜,考夫曼模糊了这两种不同的风格,使之变得都平凡无奇,做出来的扩音效果如同笼罩着糖浆般的阴霾——他没有利用话筒技术来刻画出不同的音乐风格。

从内容的角度来看,那个晚上不像一场音乐会,更像是新唱片的发行派对。那些曲子要是录入唱片中,效果肯定要比现场演出好得多,因为录音师可以进行多层面的调整。但我依旧疑虑重重——虽然考夫曼是歌剧明星,可若是一位懂得怎样善用话筒的二流歌厅歌手,那些歌曲也许会更加动听。

***

那周我在卡内基音乐厅待的日子太多了,仅仅腾出一点时间去看《一英里长的歌剧》(Mile-Long Opera

)——那是近期纽约最火爆、最难得一见的制作,一票难求。几位看过《一英里长》的朋友——他们之中有人宁愿放弃卡内基——忠告我:“记得穿舒服的步行鞋。”事后我终于明白为何只得到这样的提示,因为要描述《一英里长》真的太难了。提供实用的建议比试图解释要容易得多。我们要从“高线公园”(High Line)说起。从前在曼哈顿的西边有一条荒废多年的悬空铁轨,后来被改建为市内公园,如今成为纽约的新地标。今天的高线公园是一个难能可贵的、为市民而建的项目:是旅游胜地,最重要的是为当地人服务。自从差不多十年前建成以来,这个项目一直刺激着邻近老街区的复兴。时至今日,这一带的新建筑到处林立。

可是,具有前瞻性的Diller, Scofido + Renfro建筑设计公司除了设计高线公园以外,把目光放得更远。只做建筑,未免太局限。首席建筑师伊丽莎白·迪勒(Elizabeth Diller)的设计理念也将装置艺术和多媒体制作考虑进去。她认为高线公园的独特性在于,艺术家可以有机会为它创作特定场所可以展现的新作品。

《一英里长的歌剧》的副标题是“7点钟的传记”(“A biography of 7 o’clock”)。一开始,主创团队找来了不同背景的纽约客,询问他们“7点钟对你意味着什么?”收集到的答案——有的平淡无奇,也有的缅怀过去——由诗人安娜·卡森(Anna Carson)与作家克劳蒂亚·朗肯(Claudia Rankine)挑选及整理,然后由普利策得主作曲家大卫·朗(David Lang)谱曲。

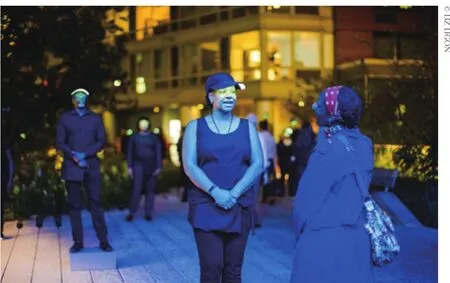

迪勒与联合导演林西·佩辛格(Lynsey Peisinger)合作,在全纽约招募了数百名歌唱家和十多个合唱团,在整个高线公园上形成了沿途的“真人装置”。让我用上些流行术语:这场演出既是“场所特定”又是“浸没式”。跟其他用上这些词汇定义的作品不同,《一英里长的歌剧》缔造出令人信服的魔幻效果。

令我感到兴奋的原因是,大家司空见惯的角色被颠覆了。跟通常的剧场演出刚好相反:演员留在原位固定不动,观众却要沿着高线公园走一遭;跟常见的装置艺术刚好相反,观众看到及听到一个梳理得很清晰(尽管较为分散)的故事;跟习以为常的高大上的歌剧艺术刚好相反,你没有胁迫感,也不用担心必须有艺术修养才可以理解这部作品。也可以这样说:这部歌剧是高度风格化的、在街上无意中听到陌生人讲话的经历。

演唱者们以个体为单位,排列在整条高架线上,从南入口至北出口都是站立的演员——在途中几个出口附近,聚集成大型合唱团——他们代表着不同的年龄、种族、声线和体形。一位歌手的单独歌词常常被下一位歌手重复,所以一些简短的叙述——比如说,对家庭聚餐的回忆——在中年黑人男子、老犹太妇女或年轻越南女孩重复时,产生了截然不同的印象。每每提到附近新建高楼的段落——沿途新建的大厦和周边的几栋建筑也被纳入演出中,某些面对高线公园的大窗户刻意地灯火通明,演员在里面表述着相关的歌词——显然,这些场景中突显的老区已不复存在,我们只能抱着怀念。是的,这场演出也有运用到话筒——作品进行到尾声的北出口。在那里,电子音响把街道的杂声构成全方位立体声,并且加入了人声。

有些表演者似乎是喃喃自语,有些则渴望跟观众打成一片。偶尔,演员们会与观众四目相接,然后又移开视线。倘若是在艺术圈工作的观众,很有可能在演员群中碰到老朋友。尽管我不太确定演出的观众须知,主办方提醒大家避免说话,但允许非强制性的身体接触,鼓励玩自拍,甚至可以飞吻。

真的是“一英里长的歌剧”吗?其实,更像是“一小时长的咏叹调”。歌剧这门艺术在风格上有一个广为人知的特点——会突然停下叙事的进展,让剧中人有机会深究感情核心——在这场演出之中,这种情况被连续重复了数百次。整个演出覆盖的路线其实是1.5英里(如果精细计算的话),观众沿途“窃听”到邻居们内心深处的想法。尽管我们沿途走了90分钟,高线公园的时间依旧停留在7点。

这些年来我很少会在走出“场所特定”的艺术演出时,还有那么强烈的“根深蒂固”共鸣之感。我经常到处飞行——看完《一英里长》隔天的凌晨我就又登上飞机——但我感到我的一部分仍然与下西城区牢固地连接着。朋友圈中只有两位批评《一英里长的歌剧》过分炒作。他们俩都不是纽约人。

Many years ago I discovered how little time you have to spend in New York to make people think you really live there.All you have to do is pick a few key events when everyone you need to see turns up.For me that would be the Musical America holiday party, the New York Philharmonic Chinese New Year gala and opening night of the Carnegie Hall season.Any two of the three will do.

Lately, it’s been only the Carnegie Hall opening.It was, like most gala evenings, basically an excuse for a party.Afterwards, that is, for people paying big bucks.The performance basically marked time between cocktails and dinner.

As party bands go, however, Carnegie Hall could’ve done a lot worse than the San Francisco Symphony.Especially by that orchestra’s standards, the program was really a pops concert—opening and closing with Gershwin’sCuban Overture

andAn American in Paris

,with sopranos Renée Fleming and Audra McDonald alternating numbers in between (and eventually singing together).Everything seemed lovely until they pulled out…the microphones.I looked across the aisle two rows ahead to Anthony Tommasini, just to monitor his reaction.For more than 20 years now, the chief music critic of theNew York Times

has led an unrelenting campaign against amplified voices.Those who take it upon themselves to safeguard tradition have certain benchmarks, and high on Tony’s list is a blanket condemnation of microphones anywhere in the concert hall or opera house.The reasoning seems rather clear:Both the venues and their most representative repertory pre-date electronically enhanced sound.Once you give singers a microphone, how can you judge the quality of their natural voice? For him, amplification is the aural equivalent of plastic surgery.It was hard to tell from the angle, but as I glanced at Tony I think I actually saw him smiling.Was this a recent change of heart? A midlife mellowing of standards?Most likely he too was in party mode, putting his critical values on hold until the San Francisco Symphony’s all-Stravinsky program the next night.

I don’t, frankly, share Mr.Tommasini’s disdain of the microphone.Plenty of recent works—let’s say, pieces younger than me—have been written specifically with amplification in mind.Since the days of, say, Frank Sinatra—who, let’s be honest, was born a bit earlier than Mr.Tommasini—the microphone has been a key component of our sonic consciousness.Waging a campaign against microphones is like trying to ban the electric guitar.

And yet, that night I felt myself being pulled to Tony’s side of the aisle.It wasn’t the microphones I had problems with:it was that they were being used sobadly

.The electric guitar isn’t a frivolous comparison.Despite the fact that singers are taught from the start that they are special—that their artistry touches the listener directly, unlike pianists or violinists who must make their way through a glorified block of wood—that is not always true.Any pop singer is well aware of what the microphone represents.It doesn't just make the voice louder; it changes the very quality of the sound.A singer needs to approach the microphone as an instrument unto itself, aware of specific techniques required.

In terms of artistry, pairing Fleming and McDonald was a stroke of genius.Fleming is arguably America’s most celebrated opera singer, McDonald perhaps Broadway’s most awarded living performer.Each has increasingly crossed over into the other’s professional turf.Each (as they announced that evening) has separately recorded mash-ups of Stephen Sondheim’s “Children Will Listen”fromInto the Woods

and Richard Rodgers’ “You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught” fromSouth Pacific

without realizing the other one did the same.When it came to the microphone, however, only one of them knew what she was doing.McDonald wielded the device like an extension of her own arm.Fleming ignored its presence completely—a charming ploy,perhaps, to keep it from getting between her and the audience.But when it came to coloristic shadings—and in particular, changes in volume—she forgot the basics of pulling the microphone closer and farther away.

But that was opening night.Lapses are easily forgiven.Two nights later, Jonas Kaufmann (on a break from rehearsals forLa Fanciulla del West

at the Metropolitan Opera) made a rare solo appearance at Carnegie Hall with the Orchestra of St.Luke’s.The program was a mix of Weimar songs from stage and screen dubbed “the Roaring Twenties of Berlin.” And standing on stage directly in front of Kaufmann was…a microphone.To be honest, I didn't really study the songlist before I arrived.Nor, I’m sure, did many Kaufmann fans in the audience.Just his name was enough to fill the hall.What I expected, though, was that a certifiable star would be using some of that box-office appeal to introduce listeners to his guilty pleasures, either the songs he grew up with or the stuff he plays once he’s done singing opera for the night.

We've all seen examples before:Placido Domingo performing zarzuelas, Bryn Terfel singing Broadway songs by Lerner and Loewe, Kiri Te Kanawa crooning Gershwin.But each of those singers—even Te Kanawa,whose Gershwin recording made Norman Lebrecht’s infamous list of 20 worst recordings ever made—was obviously singing something close to their heart.

《一英里长的歌剧》剧照

Nothing in Kaufmann’s performances would indicate that he’d even heard the songs before, let alone grown up with them.As a dessert, they were all cream with very little crust, much less a filling.

上、右页:《一英里长的歌剧》剧照

“I don’t really need the microphone,” he told the Carnegie audience, laughing that he wasn’t so old that his voice couldn’t fill the hall.Actually, he did need the microphone; he just wasn’t sure how to use it.Film songs like Robert Stolz’sIm Traum hast du miralleserlaubt

came from a sound world where the microphone reigns supreme.Selections from stage shows such as Lehár’sMerry Widow

andPaganini

required more traditionally operatic firepower.And yet, Kaufmann blurred both styles into a rather generic, amplified syrupy haze rather than using the microphone to hew their distinctions.As far as content goes, the evening was less of a concert program than an album release party.The song selection might fare better on recording, where an engineer could determine the appropriate levels.But somehow I doubt it.Kaufmann’s operatic stardom notwithstanding, the songs would’ve been far better served by a second-rate cabaret singer who knew how to use a mic.

***

I’d spent so much time that week at Carnegie Hall that I barely made it toMile-Long Opera

, which was that week’s hottest ticket in New York.Several of my friends who’d already seen the production—some of whom blew off Carnegie Hall—would only tell me, ”Wear comfortable shoes.” Which in retrospect was probably all I should’ve expected, since offering practical advice forMile-Long Opera

was a lot easier than trying to explain what it was.It all started with the High Line, a former elevated railway on Manhattan’s West Side turned into an iconic urban park.The High Line has become that rarest of civic projects:a tourist destination that is, above all, meant for locals.Since its opening nearly a decade ago, the project has spurred nothing less than an architectural renaissance in a famously rundown neighborhood.

But Diller, Scofido + Renfro, the visionary architecture firm responsible for the High Line, was hardly content just to provide the physical structure.Lead architect Elizabeth Diller, whose design work also embraces installation art and multimedia performance, saw its uniqueness as an opportunity to develop an equally unique piece of site-specific art.

The Mile-Long Opera

, subtitled “A biography of 7 o’clock,” began by asking a broad range of New Yorkers“What does 7 o’clock mean to you?” Responses from the prosaic to the nostalgic were parsed and configured by poet Anna Carson and essayist Claudia Rankine and set to music by the Pulitzer Prize-winning composer David Lang.Working with co-director Lynsey Peisinger, Diller recruited hundreds of singers and more than a dozen choruses throughout the city to fashion essentially a human installation throughout the High Line.It was both “site-specific” and “immersive,” to use a couple of the buzzwords these days.It was also, unlike most works brandishing those credentials, truly magical.

Much of the thrill came from inverting the usual roles.Unlike most theatre,Mile-Long Opera

kept its performers in place while audience members traversed the venue.Unlike most installations, sights and sounds within conveyed a distinct (if diffused) sense of narrative.Unlike most Great Art, there was a very low intimidation factor.If anything, the piece was a highly stylized version of overhearing strangers on the street.Individual singers filled both edges of the High Line—at exit points, they were gathered in large ensembles—representing every conceivable age,ethnicity, vocal style and body type.Individual vocal lines from one singer were often repeated by the next,so a few brief narratives—say, a recollection of a family dinner—created distinctly different impressions when repeated by a middle-aged black man, a old Jewish woman or a young Vietnamese girl.For every account celebrating new high-rises in the neighborhood—and several surrounding buildings were co-opted into the show, with illuminated installations in glass windows to illustrate certain vocal lines—there were telling reminiscences of the old neighborhood lost on the ground.And yes, there were even microphones—though they came mostly at the end, bending a few voices into an electronic soundscape of ambient street noise.

Some performers seemed to mumble to themselves.Others were eager to reach out.Every so often, eyes would meet, making a momentary connection before moving on.Audience members, particularly those who work in the arts, ran the risk of running into performers they knew.I’m not entirely sure of the protocol,but it seemed that speaking was strictly forbidden,non-obtrusive physical contact tolerated, selfies encouraged and air-kisses thoroughly acceptable.

Mile-Long Opera

? "Hour-long aria" was more like it.One stylistic feature that opera is famous for—stopping narrative time while focusing on a character’s emotional core—was repeated sequentially hundreds of times.For about a mile and a half (if we want to be precise), listeners got to eavesdrop on their neighbors’innermost thoughts.After 90 minutes of walking the High Line, it was still 7 o’clock.Rarely have I left a “site-specific” work feeling so sublimely rooted.As much as I fly—and I was on a plane again by midnight that night—part of me still remains fixed to the Lower West Side.I heard from only two people who didn't thinkMile-Long Opera

deserved the hype.They weren’t from New York.