The role of the teaching practice in undergraduate medical education:A perspective from the United States of America

Michael D. Fetters , Joanna Rew , Joel J. Heidelbaugh

Abstract This article describes and reflects on the role of teaching practices in undergraduate medical education on the basis of teaching experience in the United States of America. China in particular, but also other family medicine– emerging countries, continues to embark on a path of creating and embracing a family medicine– centric system. The purpose of this article is to provide a US perspective on teaching priorities and strategies for medical students, and how these fit into a larger structure of the family medicine clinical clerkship. We emphasize knowledge, clinical skills, clinical behaviors, and strategies for succeeding as a preceptor. We introduce key aspects of the University of Michigan family medicine clerkship and the highly effective structure provided by the leadership of the course directors.This organizational structure provides a framework for implementing the family medicine clerkship for teaching medical students. As China and other family medicine– emerging countries increasingly embrace the discipline, we hope these ideas will provide a meaningful reference.

Keywords: Primary care; general practice; medical education; clinical clerkship; family medicine practice; teaching; consulting skills

Background

When attending a primary care conference in Beijing in November 2017, the lead author (MF)was inspired by the presentation entitled “ The Role of the Teaching Practice in Undergraduate Medical Education” by Patricia Houlston [ 1].In conjunction with the publication of her article, this article is based on the experience of the lead author as a medical educator at the University of Michigan, where he has taught as a faculty member since 1994, and on the approach used in the current family medicine clerkship program, as well as on the experience of one of the coauthors (JH) as a medical educator at the University of Michigan since 1999 and clerkship director since 2007.This article is particularly timely as in 2018 the University of Michigan Department of Family Medicine marked 40 years since its establishment in 1978 [ 2]. In addition, 2018 marks the University of Michigan Medical School’ s 168th year of the teaching of future physicians since its establishment in 1850 [ 3].In this article, we consider family medicine and general practice to be the same specialty, although we use family medicine in reference to the United States as this term predominates there,and we use general practice for quanke yixue, the term predominantly used in China.

Considering various models of teaching family medicine is timely. In many countries around the world family medicine is still an emerging specialty [ 4 – 8]. There is increasing interest in finding practical approaches to support the growth of teaching and evaluation in family medicine–emerging countries [ 9]. In 2010, China set an impressive goal of achieving 300,000 general practitioners (GPs) for a ratio of two to three GPs per 10,000 population in China by 2020 [ 10, 11]. In this decade, there has been impressive progress (e.g., 209,000 GP physicians in 2016 [ 12]). Even more striking, in January 2018, the Chinese State Council announced plans to create an additional 500,000 GPs, with a target ratio of about five GPs per 10,000 population by 2030 [ 13]. To put the magnitude of this plan in context, in 2015, there were roughly 23,000 US medical school graduates from allopathic and osteopathic medical schools [ 14].With current or even an expanded capacity, it would take more than two decades and require every US medical school graduate to become a family physician to achieve a target of 500,000 new GPs.

Models of family medicine education internationally

The existing global family medicine literature about medical students falls into several categories. Globally, personal characteristics and experiences have significant associations with specialty preference for medical students [ 15 – 19]. A personal conviction based on illness in oneself or close others also influences a choice in family medicine [ 18, 20]. A previous connection or affiliation in a community predicts willingness to practice in such a setting [ 19, 21]. Student preferences are favorable in countries with supportive social policies for family medicine [ 17, 22] and unfavorable in countries with unfavorable social policies for family medicine [ 23, 24]. The specifics of differences in family medicine practice are unknown, but they are likely influenced by significant variations in medical education approaches across Asia in general [ 25].

The imperative to meet China’ s laudable goal emphasizes the value of considering various training approaches for family physicians. In the spirit of providing a reference for China and for other family medicine– emerging countries, the purpose of this article is to introduce outpatient teaching of family medicine at the University of Michigan.

The undergraduate medical education system at the University of Michigan

Medical students at the University of Michigan have completed a bachelor’ s degree before matriculation, and some have completed a master’ s degree, a doctorate of philosophy,or other advanced degree. Moreover, the medical school gives students flexibility to pursue advanced degrees in a combined dual-degree program in medicine, plus an additional degree in research, or fields such as law, public health, or business administration.

The University of Michigan was one of the first medical schools recognized as having a scientifically based curriculum in the highly influential Flexner report published in 1910 [ 26].Over a century later, the University of Michigan received grant funding from the American Medical Association for innovation and advancement of the medical curriculum for the 21st century [ 27 – 29].

Several activities by the department faculty promote family medicine to medical students. Family medicine faculty serve as instructors and advisors in educational tracks such as global health and disparities and leadership, as well as doctoring courses. The department supports a family medicine interest group, a student-run organization designed to expose students to family medicine and to promote the specialty.The most important exposure of medical students to family medicine occurs during the required family medicine clerkship. From 1996 until 2017, the clerkship at the University of Michigan was in the third year of medical school but since 2018 it occurs along with other required clerkships in the second year of medical school under the new curriculum [ 30].Herein we offer a perspective on family medicine teaching priorities and strategies for medical students, and how these fit into a larger structure of the family medicine clinical clerkship.

Lessons from the field: experience with teaching medical students family medicine

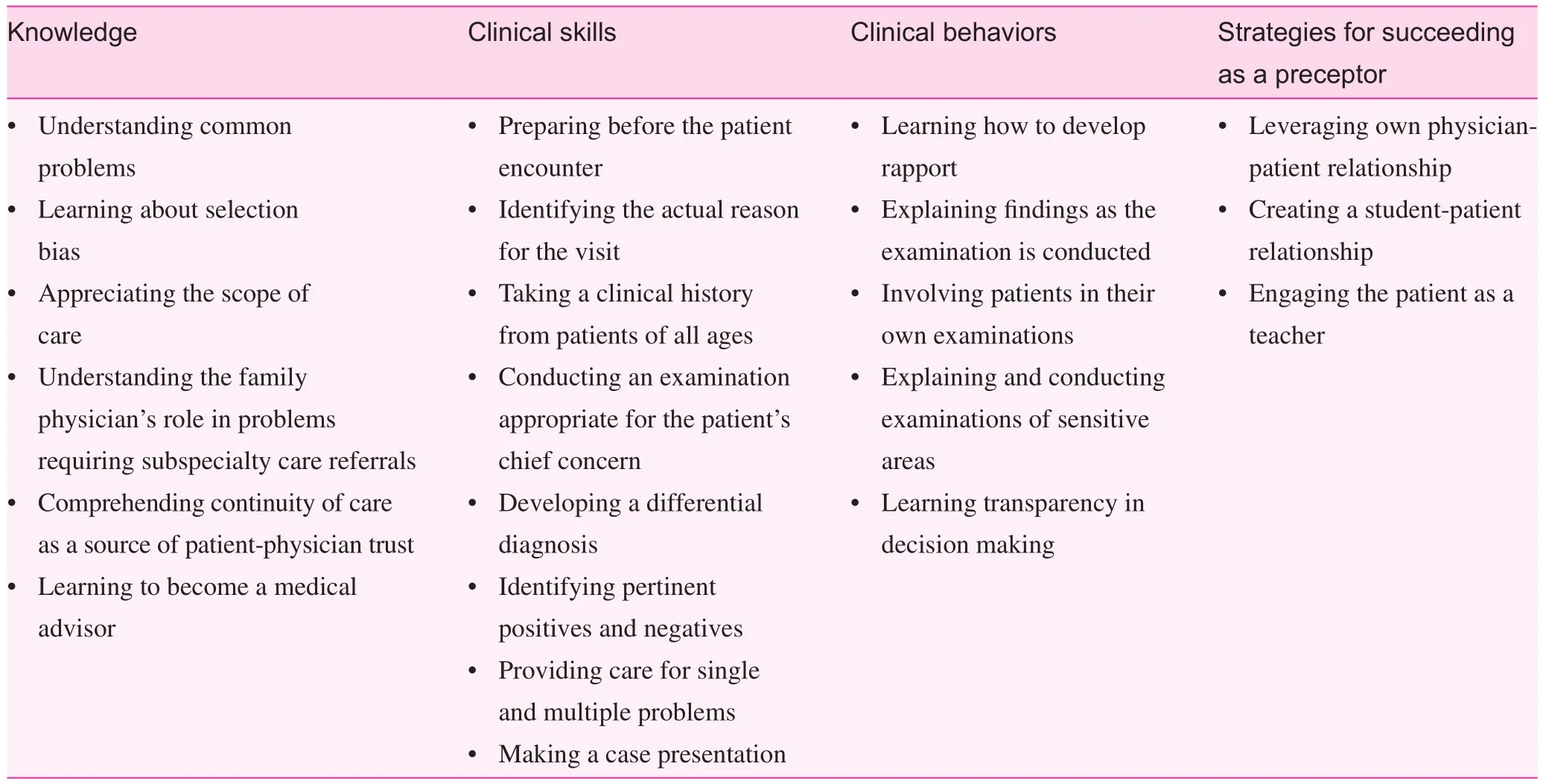

On the basis of more than 25 years of serving as a teacher of medical students, both from the United States and from an active exchange program with Japan, the lead author has provided an overview of his goals for medical students during the family medicine clerkship as illustrated in Table 1. University of Michigan faculty strive to have medical students on clinical rotations function at the highest level possible for their clinical skill level, and then support their growth to higher levels during the rotation. The goal by the end of the family medicine rotation is for students to become as competent as possible relative to taking a history, conducting an examination, forming a differential diagnosis, developing a treatment plan, presenting patient cases, and writing notes in the medical record.

Knowledge

Understanding common problems: In a family medicine clerkship, students can develop an appreciation for common problems managed by family physicians across acute care,chronic care, and preventive care for patients of all ages and both sexes. A key point is that common problems do not necessarily equate to simple problems. Acute care for asthma,chronic care for diabetes, depression, or dementia, and consistent and comprehensive delivery of preventive services all require high-level cognitive and behavioral skills. Students learn this breadth of care best by seeing a wide variety of patients during their family medicine rotation.

Learning about selection bias: Medical students, especially after experiencing rotations on academic hospital services, may develop an obscured view of what constitutes the most common medical problems because of selection bias [ 31,32]. From their family physician preceptor, students see a new range of problems, and recalibrate their thinking relative tothe common problems of hospital versus primary care settings through discussion of the differential diagnosis.

Table 1. Teaching goals for medical students undergoing rotation in family medicine

Appreciating the scope of care: While data specific to family physicians are lacking, in 2009 primary care physicians in the United States referred about 10% of their patients to other specialists, although the trend had increased from about 5% since 1993 [ 33]. The referral rates are sometimes misinterpreted, as primary care and family physicians care for only about 90% of their patients. The correct interpretation is that family physicians care for 90% of their patients ’ presenting problems and 100% of their patients. That is, in addition to care of the 90% of patients’ presenting problems, students learn how family physicians take responsibility for ensuring that 100% of their patients, including those that are referred,experience satisfactory evaluation, treatment, and care.

Understanding the family physician’ s role in problems requiring subspecialty care referrals: When a patient’ s problem prompts referral for subspecialty care, family physicians often initiate appropriate diagnostic testing and start an empiric course of therapy. Students learn how family physicians provide initial care of patients to facilitate decision making at the time of the visit, even when patients are referred to subspecialists.

Comprehending continuity as a source of patientphysician trust: Helping students understand the importance of continuity requires students to observe and experience how trust between the physician and patient enhances the quality of care. Trust is enhanced when family physicians arrange for patients to be seen outside office hours, with a specific consulting physician, or by contesting prescriptions or treatments denied by insurance companies. Students learn the value of continuity when they see the same patients a second or third time and witness firsthand how previous knowledge of the patient enhances care (e.g., evolution of a symptom, or response to a trial of medication).

Learning to become a medical advisor: When patients receive recommendations for treatment from subspecialists,they often want the second opinion of the family physician they trust. Students can witness the bene fit of the neutral perspective of the family physician assisting in patient decision making when seeing a patient who has been advised to undergo cardiac ablation versus medical therapy for an arrhythmia by a cardiologist or lumpectomy versus chemotherapy by an oncologist.

Clinical skills

Preparing before the patient encounter: Students often need help learning how to prepare for a patient consultation.For patients with multiple chronic medical problems, students need guidance on efficiently reviewing and prioritizing problems from the patient’ s medical history before the patient encounter. Preceptors give advice on the skills for quickly finding resources for self-learning.

Identifying the actual reason for the visit: Medical students often struggle with identifying the underlying reason for a patient seeking consultation. Students learn about two common patterns. First, students learn about the patient who is too embarrassed to express the underlying problem, such as a male patient who reports a vague history of abdominal pain who actually has concern for a sexually transmitted illness or a desire for treatment of erectile dysfunction. Second, students learn to recognize patients who do not have insight into the underlying cause of their symptoms, such as a patient presenting with recurrent headaches who has underlying depression.

Taking a clinical history from patients of all ages: In their family medicine rotation, students learn approaches for directly taking a history with pediatric patients, adults of the same sex and opposite sex, and seniors, some of whom may present with mild dementia or cognitive impairment. A rather common tendency is to start history taking with the mother or father who has brought the child, or a family member who has brought an elderly parent. The preferred approach is to start with the patient.

Conducting an examination appropriate for the patient’ s chief concern: The wide variety of problems seen in family medicine means that medical students must become comfortable taking a history for a variety of common concerns and conditions. This requires students to acquire and master technical skills to conduct a physical examination using commonly available equipment, including an otoscope, ophthalmoscope,or speculum for cervical cancer screening. It also means students learn common outpatient procedures, including conducting a vaginitis test, microscopic urinalysis, or skin scraping for fungal elements and examination under the microscope.

Developing a differential diagnosis: Students have the opportunity in an outpatient clinic to develop a differential diagnosis appropriate for primary care patients with undifferentiated problems. This differs from the differential diagnosis for problems encountered in the hospital setting. One teaching strategy one of the authors (MF) has found effective is to ask the student to consider the three most dangerous problems and the three most likely problems. For a 26-year-old woman presenting with right lower abdominal pain, three common dangerous problems (and in this scenario there might be more) might involve ectopic pregnancy, appendicitis, or ovarian torsion,while the three most likely problems could include constipation, urinary tract infection, or sexually transmitted infection.

Identifying pertinent positives and negatives: A challenging skill for medical students to acquire is learning how to identify pertinent positives and negatives from the history and physical examination. Identifying pertinent positives and negatives is an extension of developing a differential diagnosis based on competently taking a history and examining a patient for the diagnoses primarily under consideration.

Providing care for single and multiple problems: Most medical students do not start their family medicine clinical rotations prepared to obtain and present a concise history based on the scope of the visit. There is much less time than in the inpatient setting where patients are present continuously. Students learn to practice a variety of case presentations, from very focused for a single acute problem, to more comprehensive for a patient with multiple medical problems. Students learn the skills of providing acute, chronic, and preventive care through a single encounter.

Making a case presentation: Making an appropriate case presentation is a critical skill that can be sharpened during the family medicine rotation. Family medicine preceptors seek to help students develop presentation skills appropriate to the clinical findings by instructing them to make a list of problems in descending order of importance, and then developing an appropriate differential diagnosis for undifferentiated problems.

Clinical behaviors

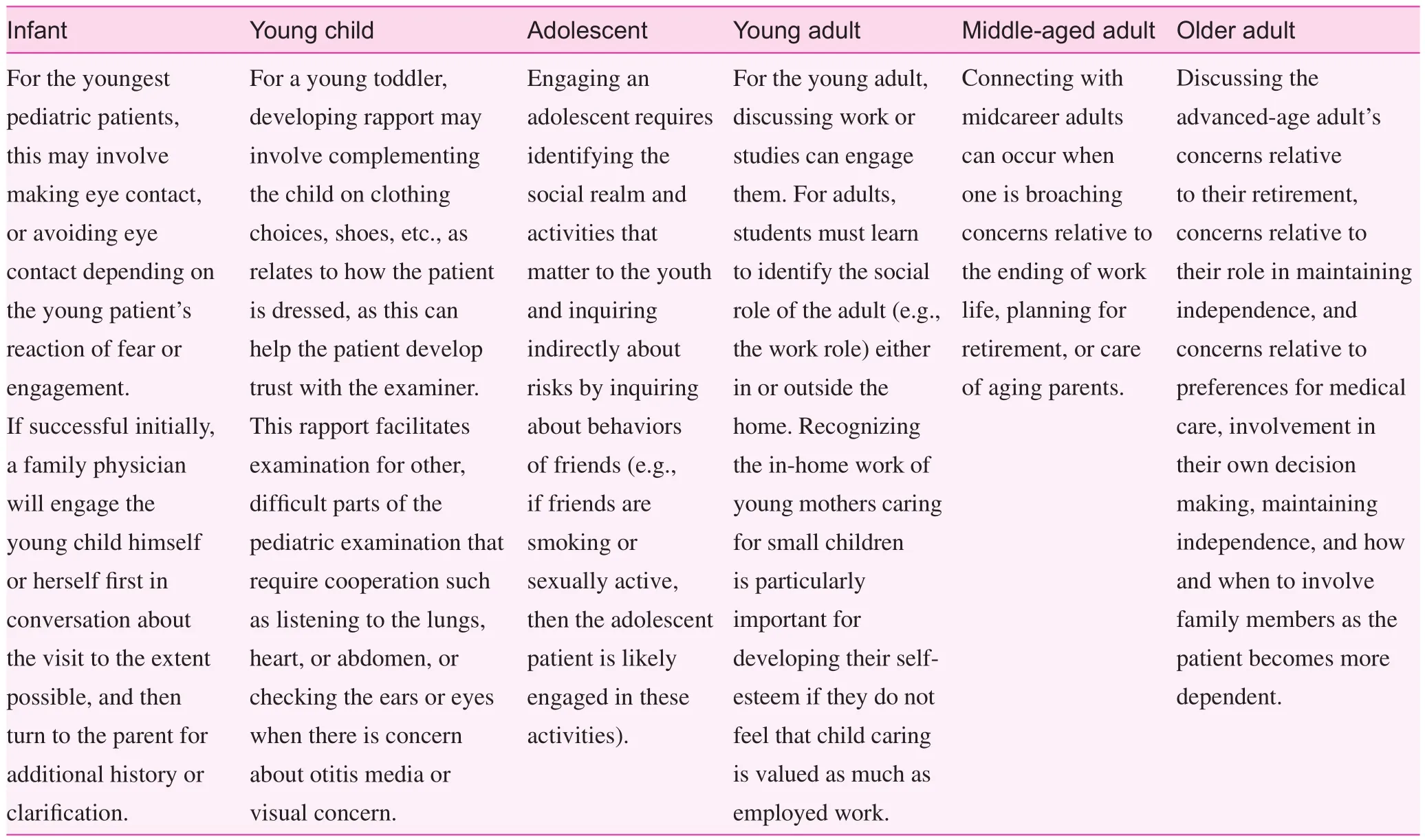

Learning how to develop rapport: Assisting medical students with obtaining the skills for developing rapport with patients of all ages is critical. Initial rapport building illustrates the family physician’ s commitment to recognizing any patient,regardless of age, as a person. From young children to adults of advanced age, approaches for finding a focus for initial conversation and rapport building students can emulate can be found in Table 2.

Explaining findings as the examination is conducted:A practical skill for students to learn is disclosing findings noted by the family physician while conducting the physical examination. For example, for a patient with a concern of “ ear pain,”explaining the findings seen as the ear is examined – whether an effusion is present or not in the middle ear, there is erythema,or there is tympanic membrane retraction – engages patients in their care. Patients find comfort when hearing findings are normal, and disclosure of abnormal findings prepares them for a treatment plan conversation. Students learn that communicating physical findings during the examination is possible under even the busiest of circumstances and helps convey to patients the student’s competency in clinical medicine.

Involving patients in their own examinations: Family physicians excel in the patient-centered examination that can be modeled and taught to students in several ways. This involves the physician giving a hand to a patient with pain, who then uses the physician’ s hand to palpate the area of pain. By using the examiner’ s hands, the patient is in control to help minimize the pain caused by the examiner, and the patient’ s use of pressure with the physician ’ s hands provides valuable information about the severity, location, and nature of the pain.For a young child, the child the stethoscope to hold in his or her own hand while the physician takes the child’ s hand and stethoscope to listen to the heart or abdomen gives the child the feeling of control. Before the physician examines a child’ sear, showing the shiny light of the otoscope on the child’ s fingers and allowing the child to touch “ the light” alleviates fear and engages the child. When a family physician uses the patient’ s finger to show that patient a lump (e.g., a breast lump in women), students have the opportunity to see how family physicians engage patients with their care and help them understand their bodies.

Table 2. Approaches medical students can use to build rapport with patients

Explaining and conducting examinations of sensitive areas: The physician, and especially student, examination(strictly under supervision) of sensitive areas, such as the testicles or prostate/rectum of a male patient, and the breasts or genitalia of a female patient, can be highly anxiety provoking for patients and students. Especially for these examinations,students need to explain the intent or rationale of particular examination maneuvers, and the findings. For example, students can learn to explain the rationale for visual inspection of the breasts, to look for dimpling or skin color changes, while conducting the examination. Students can also learn to empower the patient as a voluntary partner during the examination. One modeled technique for students learning how to engage a female patient in a pelvic examination is to have the patient abduct her thighs to the gentle tapping on the outside of the thighs and request her to open her thighs wider to facilitate insertion of the speculum rather than the examiner pushing the thighs apart.

Learning transparency in decision making: Transparency is the process of the physician making clear to the patient the physician’ s own thinking or decision-making process about the patient’ s problem [ 34]. The art of transparency in communication may be a common pathway to rapport, trust, and minimizing malpractice that is worth modeling and emphasizing to students [ 35].

How to succeed as a preceptor

The Society of Teachers of Family Medicine strongly supports family physician teaching of medical students [ 36]. For more details, readers may be interested in publications focused on efficient teaching approaches [ 37], how to involve students in the era of the electronic health record [ 38], and gaining efficiency by precepting in the presence of the patient [ 39]. A full review of these tips is beyond the scope of this article. Rather,we highlight several tips based on experiences in teaching that are particularly salient:

• Leveraging the physician-patient relationship. Students need advocacy of their preceptor for patients to trust them. Having a family medicine preceptor request the patient to allow the student to conduct an examination works well generally in family medicine offices because of the physician’ s own relationship of trust with the patient.

• Creating a student-patient relationship. Over time, we have observed the importance of involving the student early in the patient’ s visit. When a student establishes rapport directly with patients through initial discussion and history taking, patients feel more comfortable permitting the student’s participation in the physical examination. A request from the family physician for the patient’ s permission to allow the student to conduct a physical examination, especially of sensitive areas (e.g.,breasts, pelvic, testicular, and rectal areas) is much easier if the student has already established rapport and a relationship with the patient.

• Engaging the patient as a teacher. A valuable mechanism to avoid dehumanizing patients as objects of a physical examination is to engage the patient as a participant in the teaching process. For example, during an abdominal or breast examination, the faculty member can ask the patient to give feedback to the student. That is, the patient is the best judge of whether the amount of pressure is nearly the same or not the same as that in the preceptor’ s examination. Does the pressure during maneuvers checking for internal integrity of the knee joint seem to be the same between the attending physician and the student? Only the patient can judge and give feedback about this modeling.

These different approaches and fundamentals are priorities and techniques that can be used for medical education within the framework of overarching goals as infrastructure of the required family medicine clerkship. In the next section, we present the organizational approach to the family medicine clerkship.

The required University of Michigan family medicine clinical clerkship

The National Clerkship Curriculum through the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine provides guidance for operating a family medicine clinical clerkship and serves as an excellent resource. Its aims are to provide a compendium of core topics and skills that clerkship directors can use as a guide to ensure consistent training and experience across institutions. The overall University of Michigan family medicine clerkship reflects the recommendations of the National Clerkship Curriculum [ 40]. The University of Michigan family medicine clinical clerkship utilizes many of the recommendations, and serves as the most important opportunity for medical students to learn about family medicine.For 19 of 22 cohorts since the establishment of the required family medicine curriculum at the University of Michigan in 1996, medical students have rated the family medicine clerkship highest among all of their clinical rotations. That is, the quality of teaching on the family medicine clerkship has been rated higher among medical students for its educational quality than any other rotation. While the University of Michigan is renowned as a leading institution for the training of leaders of many disciplines, the ranking of family medicine so highly among students who usually choose another discipline is remarkable.

The reasons for success of the University of Michigan family medicine clerkship

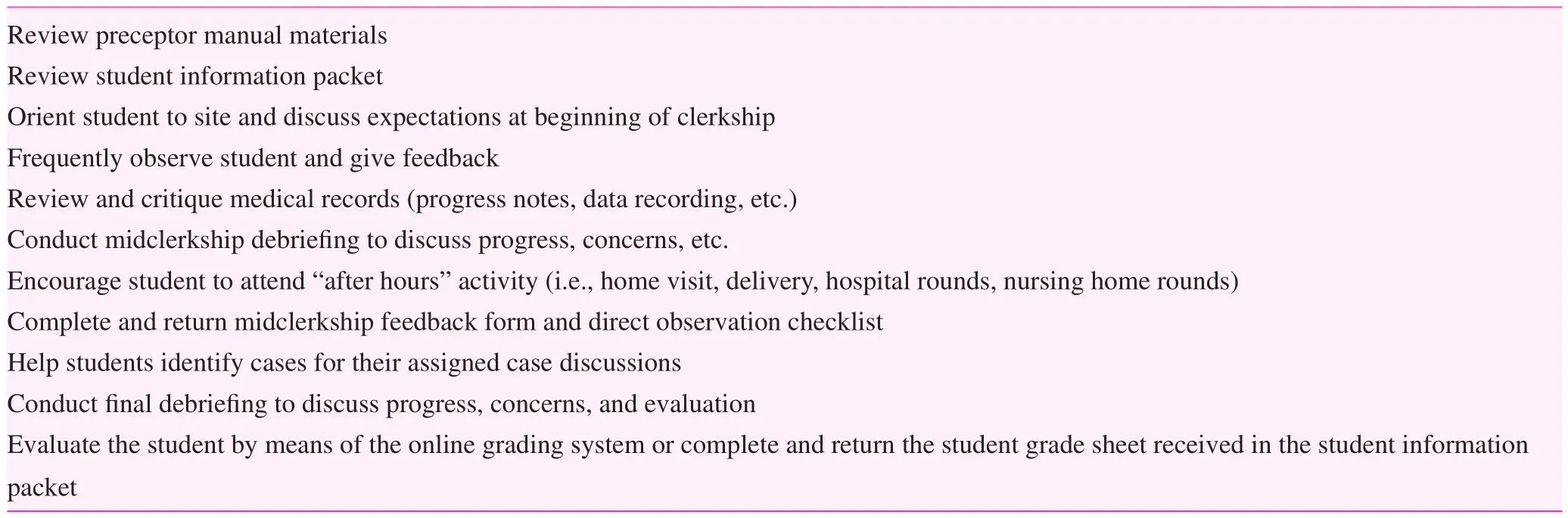

The University of Michigan Department of Family Medicine has a guide called “ The Fundamentals of Family Medicine Clerkship,” which is a manual provided to all family medicine preceptors of students as a hard copy and is also on the department intranet. This preceptor manual, which is accompanied by an informational document that outlines expectations of them while preceptors are working with a student, includes a summary of preceptor responsibilities and tasks ( Table 3),instructions for the midclerkship feedback form and directobservation checklist, a copy of the feedback form and checklist, and the overall clerkship assessment form.

Table 3. Summary of preceptor responsibilities and tasks

The clerkship lasts 4 weeks and immerses students in various clinical experiences in an ambulatory family medicine setting. Students start on day 1 independently seeing patients,presenting them to the assigned family medicine preceptor,and then finalizing the plan together with the patient under the preceptor’ s guidance. During the 4-week rotation, students are expected to gradually become more and more independent. At the University of Michigan, students typically work with multiple physician preceptors, but are assigned a primary preceptor, who provides the mid-clerkship feedback using the assessment form.

During the family medicine clerkship, preceptors are asked to directly observe students taking patient history information,their physical examination skills, and their discussion of an assessment and plan with the patient, and then provide the student with positive and constructive feedback for improvement. The goal is to facilitate the learning and development of problem-oriented skills that are necessary in ambulatory clinical settings.

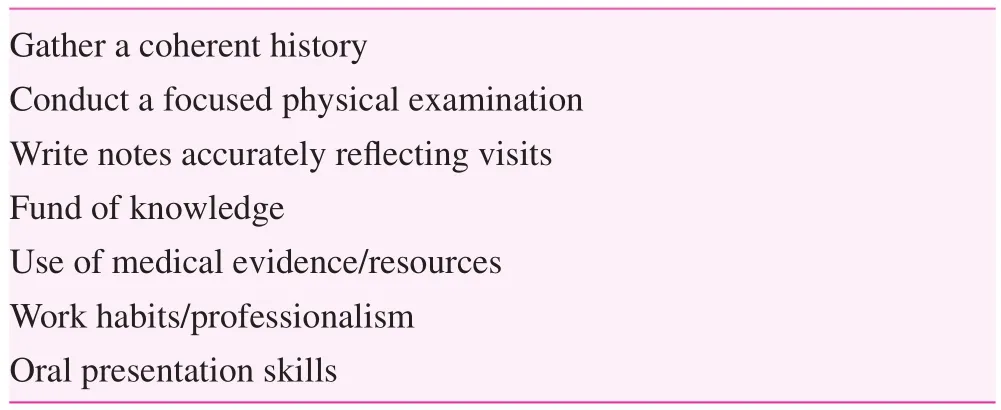

The midclerkship feedback form is to be completed when the primary preceptor meets with the assigned student midway through the 4-week rotation. Preceptors are asked to provide written feedback on two to three skills/areas (see Table 4),noting the student’ s strengths and any deficiencies, which arecoded as “ strengths” or “ needs improvement.” This feedback should be verbally discussed with the student for optimal skill development.

Table 4. Skill/areas assessed with the mid-clerkship feedback form

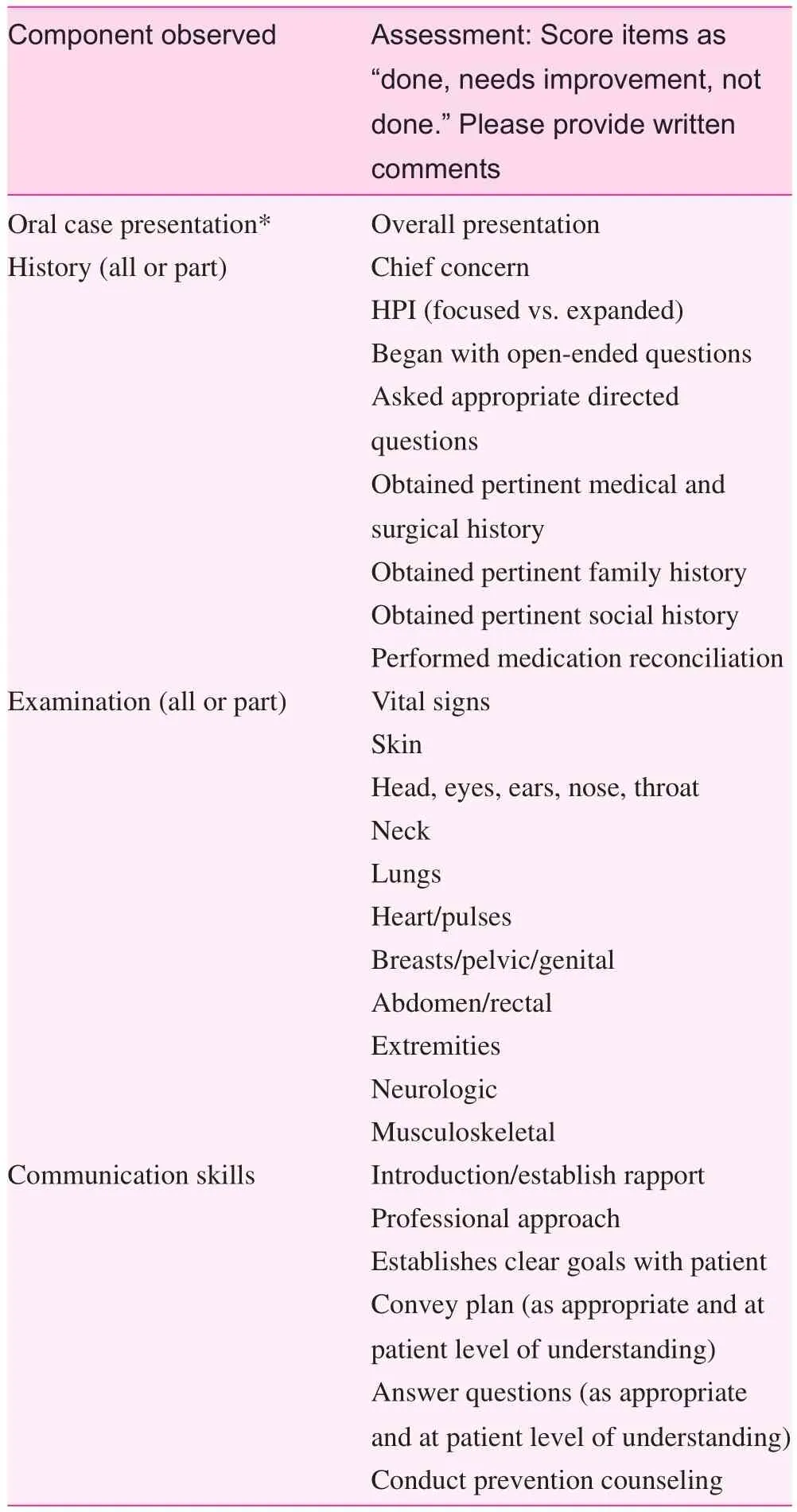

The direct observation checklist is a tool used to provide feedback for the student’ s physical examination skills as observed by the preceptor. It is acceptable for the form to be completed by multiple preceptors across various patient observations. See Table 5 for a breakdown of the components of the checklist.

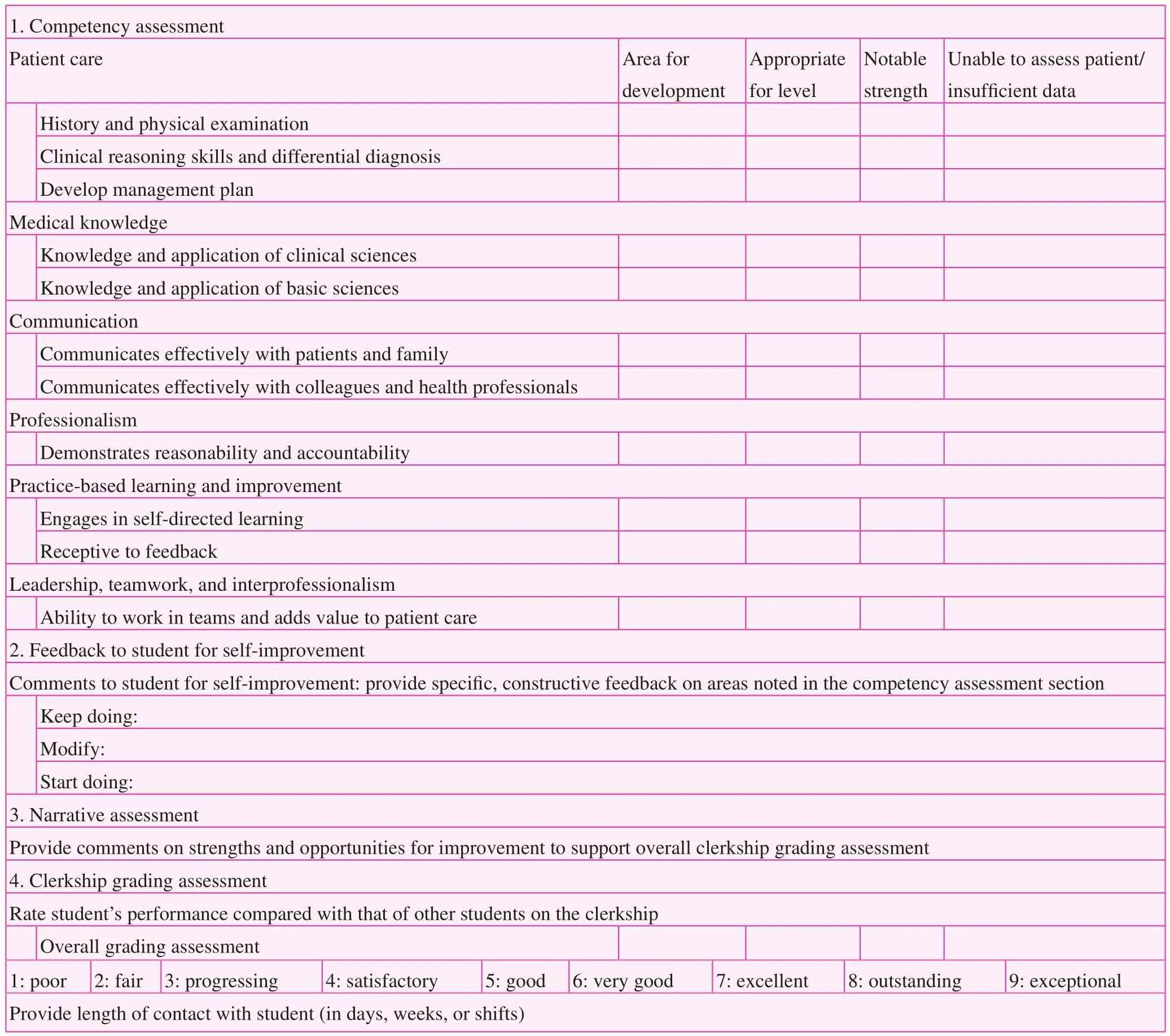

At the end of the family medicine clerkship, all family medicine preceptors who have worked with the student for at least two sessions will complete a competency assessment for the student. The assessment covers six domains (11 competencies), and provides feedback for self-improvement, a narrativeassessment, and an overall clerkship grading assessment. See Table 6 for an outline of the assessment form.

Table 5. Direct observation checklist to assess student physical examination skills

Tables 3– 6 are included as a reference for programs that might wish to adapt them to their needs. The actual unedited tables are available on request from the lead author.

Discussion

This article adds to an existing literature on approaches to clinical teaching in family medicine at the systems level [ 38]as well as at the individual level [ 1]. While limited in scope to a single institution, the article provides significant detail based on the experience of a senior professor and senior clerkship director. As many of the elements of the National Clerkship Curriculum were pioneered at the University of Michigan, the clerkship can reasonably be expected to parallel many of the same procedures in other US institutions. There may be additional experiences and approaches in other institutions. This article also expands on the current literature on the implementation [ 38] by providing templates that can be used for evaluation. Future research could examine what are the most effective interventions for promoting family medicine to medical students, and how successful such interventions are across multiple institutions.

Conclusions

In addition to providing clinical knowledge of specific types of illnesses, the outpatient setting provides an environment where students can learn about the wide variety of patients who present to family physicians, about variations in the epidemiology of illness, and how the most common problems are highly affected by the setting where patients seek care. This setting provides students with the opportunity to consider the acute, chronic, and preventive care of men and women of all ages. Family physicians have much to teach,and medical students have much to learn about the importance of continuity, rapport, and trust. The University of Michigan family medicine clerkship provides a well-articulated curriculum, has procedures for informing students of their learning strategies, and has processes family medicine preceptors can use to evaluate students.

If previous literature demonstrating favorable social policy is associated with success of family medicine [ 17, 22], the favorable social policy in China, if sustained, should also bode well for success of family medicine there. China has already made great strides in producing GPs to provide primary care.We hope this discourse will help spark ideas for faculty about the kinds of material that they can teach, as well as new teaching strategies. We look forward to the rapid development ofgeneral practice in China and other family medicine– emerging countries.

Table 6. Overall assessment form that is completed by primary preceptor at the end of clerkship

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Kent Sheets, who pioneered development of the University of Michigan family medicine clerkship and currently serves with Joel Heidelbaugh,Clerkship Director, in leadership of the University of Michigan Department of Family Medicine medical student curriculum.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no specific grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or nonprofit sectors.Dr. Fetters’ participation in the Beijing conference leading to this work was supported by the University of Birmingham,Program for General Practice Devlopment in China.

Author contributions

Michael Fetters contributed to the conceptualization, drafting,editing, and revising of the manuscript and final approval of the content. Joanna Rew contributed to the drafting, editing, and revising of the manuscript and final approval of the content.Joel Heidelbaugh contributed to the revising and editing of the manuscript and approval of the final content. All authors take responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the content.

Family Medicine and Community Health2018年3期

Family Medicine and Community Health2018年3期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Factors influencing IOP changes in postmenopausal women

- Development and validation of the Mothers of Preterm Babies Postpartum Depression Scale

- Blood pressure– controlling behavior in relation to educational level and economic status among hypertensive women in Ghana

- A cross-sectional study to assess the out-of-pocket expenditure of families on the health care of children younger than 5 years in a rural area

- Integrated primary care– behavioral health program development and implementation in a rural context

- Number, distribution, and predicted needed number of general practitioners in China*