Integrated primary care– behavioral health program development and implementation in a rural context

Kendra Campbell , Loren McKnight , Angel R. Vasquez

Abstract Objective: Despite the known bene fits of integrated primary care and behavioral health services, integrated behavioral health services have not been readily used in medical clinics in interior Alaska. With minimal resources, we recently developed an integrated primary care– behavioral health program in a medical clinic in interior Alaska to meet clinic and community needs. The objective of this study was to explore initial program outcomes and determine the feasibility of program development and implementation.Methods: We initially conducted a needs assessment for integrating behavioral health services into primary care. Program development was informed by specific clinic needs. Following program implementation, initial program outcomes were tracked with use of data from the electronic health record and patient and provider use and satisfaction surveys. The level of integration of primary care and behavioral health services was evaluated with the Practice Integration Profile.Results: A total of 188 patients were seen by behavioral health consultants during the initial pilot phase, including 44.0% referred for mental health symptoms, 33.1% referred for physical health issues, and 22.3% referred for both mental and physical health issues. The initial program outcomes indicate modest clinical improvement (measured by the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire) as well as patient and provider satisfaction with the model, and a moderate level of practice integration.Conclusion: On the basis of the initial findings, it appears that our integrated primary care–behavioral health program has the potential to serve an important role in addressing the behavioral health needs of the local population. Our implementation procedure and initial program outcomes suggest that such models are feasible in rural and small-scale settings with minimal overhead costs.

Keywords: Integrated healthcare; primary care; behavioral health; program development;rural healthcare

Introduction

As is becoming readily apparent in the healthcare literature,integrating behavioral health services into primary care medical settings offers multiple bene fits in regard to clinical cost-effectiveness, continuity of patient care, and more effective prevention and management of a wide array of physical and mental health concerns [ 1 – 4]. Integration of behavioral health services within primary care is designed to address the behavioral health needs of patients who otherwise may not be seen in a specialty mental health clinic. Integrated primary care and behavioral health services can reduce barriers to accessing mental health services,improve patient health outcomes, and facilitate interprofessional dialogue [ 1, 5]. Primary care is an opportune setting to screen patients for and facilitate treatment of behavioral health issues that may be impacting patient health outcomes, and inclusion of integrated behavioral health services is becoming a crucial factor in offering a more holistic patient treatment [ 6].

Despite the known bene fits, fully integrated behavioral health services have not been readily used in rural medical clinics in the United States. The interior region of Alaska is composed of rural villages and small communities, with the largest population living in the region’ s largest town, which is relatively small and very remote. Almost all the residents of the interior living rurally must travel to town for medical services and behavioral health treatment. However, there is limited access to health services. It is important to maximize face-to-face interactions and provision of services to patients seeking treatment in this community.

We recently developed an integrated primary care– behavioral health program in the family medicine department of a medical clinic in interior Alaska to meet clinic and community needs. Included in the current report is our outlined process from development to implementation along with initial outcomes from the 9-month pilot phase. The initial goals for program development and implementation were to collaborate with local healthcare organizations to conduct needs assessments for integrating behavioral health services into primary care. Ongoing program development and evaluation include tracking patient use of, access to, and satisfaction with behavioral health services, tracking patient clinical outcomes and identifying specific outcomes that should continue to be monitored as part of ongoing evaluation, and assessing provider satisfaction with the integrated primary care– behavioral health model. Future goals include continued evaluation of the integrated primary care– behavioral health program, including specific health outcomes and treatment cost-effectiveness. Our goal is to effect positive change in physical and behavioral healthcare delivery in this region and to provide more effective service management in rural healthcare facilities.

Methods

Program development

Setting: Our program development occurred within one of the main private outpatient medical clinics in the community with a borough population of approximately 100,000 people.The family medicine department includes 14 primary care providers (physicians and physician assistants) and serves approximately 13,000 patients. The research methods used were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Needs assessment: The first step of our process in developing a novel integrated primary care– behavioral health program in interior Alaska was to conduct a needs assessment to determine the particular needs and perspectives within one of the main outpatient medical clinics in the community. We surveyed primary care staff to assess their perceived need for and use of integrated behavioral health providers in the clinic.According to our assessment, primary care providers estimated that on a typical day up to 50.0% of their scheduled patients present with a mental health concern; for approximately 30.0%– 50.0% of these patients, the mental health issue was the sole or primary concern, and for approximately 90.0%– 100.0%of these patients, the mental health issues were exacerbating medical issues and/or impacting their medical treatment. Further, providers believed that almost all patients could bene fit from meeting with a behavioral health provider for either a mental health issue or a medical issue for which a behavioral intervention would be indicated. Our initial assessment findings suggested a definite need for integrated behavioral health services in primary care clinics in interior Alaska, especially since access to mental health services is limited in such a remote community. Encouragingly, from these results, local medical providers appeared to be very motivated to include integrated behavioral health services in their practice.

Current model: After gaining buy-in from the clinic providers and administration, we sought to develop a level 4 colocated primary care behavioral health model [ 7] to meet the clinic needs. In this model, the physical workspace and patient care systems (e.g., electronic health record [EHR]) are integrated and provider communication and collaboration is face-to-face.This model was favorable to the clinic because it maximized existing resources (e.g., workspace) without implementing a more widespread change to the clinic practice and flow (e.g.,by adding morning huddles or integrated case conferences).Notably, the primary care providers’ recognized need for integrated behavioral health services (as discussed earlier) was helpful in obtaining organizational support.

To distinguish our integrated program from the concurrently implemented specialty behavioral health service in the clinic (staffed by two behavioral health clinicians), we labeled our program Family Medicine– Behavioral Health (FMBH)and our clinicians are described as behavioral health consultants (BHCs). The model was developed and implemented with minimal resources needed from the clinic itself. The initial phase, a 9-month pilot, consisted of one lead psychologist with specialty training in clinical health and primary care psychology who was contracted to train two to four doctoral-level psychology trainees. Because the pilot FMBH program includes trainees, patients are not billed for services.

The FMBH program is a consultant model in which BHCs are colocated in the primary care clinic and available for sameday, warm handoff referrals from primary care providers. The behavioral health interventions in this setting are designed to augment usual primary care health treatment and prevention.Behavioral health visits in this model are brief and specific to the referral concern. Clinical service delivery in our FMBH model includes traditional mental health services (e.g., brief,evidence-based intervention and assessment for depression,anxiety, substance use), crisis management prevention and intervention (e.g., suicide risk assessments), evidence-based behavioral medicine interventions (e.g., behavioral pain management, chronic disease management, weight management,stress management, smoking cessation interventions), and collaboration/consultation with medical providers regarding patient care (e.g., facilitation of longer-term mental health referral; psychotropic medication risk management). All behavioral health services are delivered in the primary care setting (i.e.,in one of the clinic’ s examination rooms), and referrals are primarily via warm handoff from the primary care provider in the context of a normal primary care visit. In our initial phase,we staffed the clinic with BHCs for only 3– 4 days a week, and so also accepted electronic referrals during our pilot.

Initial outcomes measures

EHR tracking system: To track and monitor how the pilot FMBH program is working, we developed a database using the EHR to track clinic- and patient-specific outcomes. This outcome tracking included reasons for referral and patients’before and after scores on the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [ 8]. We began administering the PHQ-9 to all referred patients partway through the initial program implementation. See Appendix A for a full breakdown of the data tracked through the EHR.

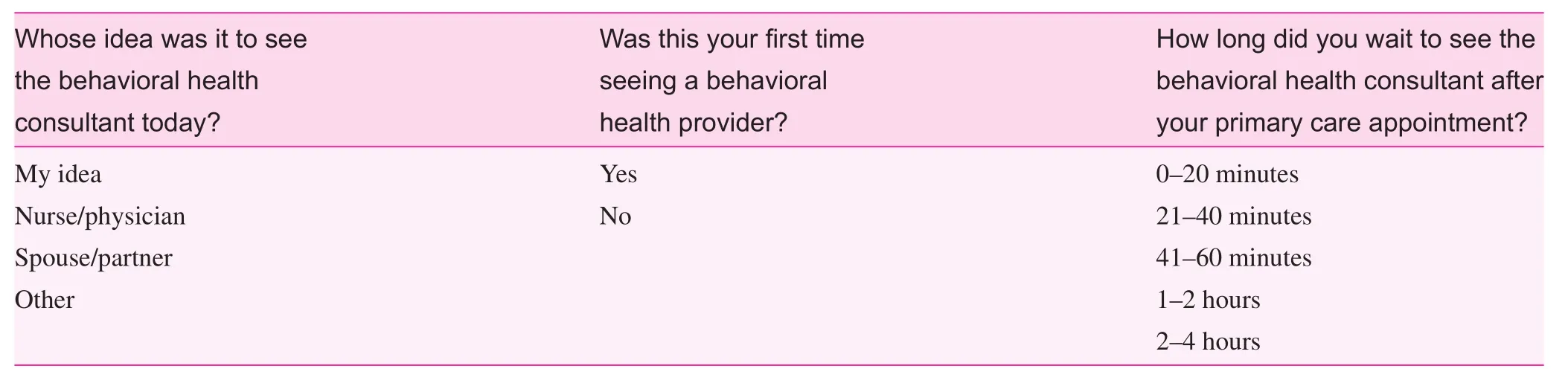

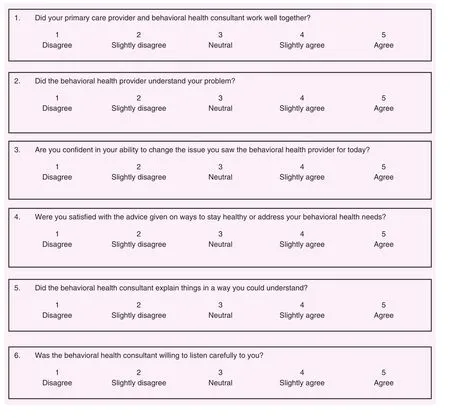

Patient feedback: Feedback from patients was requested after the initial warm handoff encounter about their experience on a short paper survey dropped off anonymously at the reception desk. Most items were on a five-point Likert scale and included questions such as “ Did your primary care provider and behavioral health consultant work well together ? ” and“ Did the behavioral health consultant understand your problem? ” See Appendix B for the full survey.

Provider feedback: Provider surveys were collected by self-report surveys via https://www.qualtrics.com/. Initial provider feedback included use of and satisfaction with the model. Most items were on a five-point Likert scale and included questions such as “ How satisfied are you with the accessibility of the Family Medicine– Behavioral Health team? ” and “ How satisfied are you with the care provided for your patients by the Family Medicine– Behavioral Health team? ” See Appendix C for the full survey.

Practice integration: To determine the current level of integration between primary care and behavioral health services in our FMBH model, the Practice Integration Profile(PIP) [ 9] was administered to the lead behavioral health clinician and clinic medical director. The PIP is a self-assessment of practice integration based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’ s Lexicon for Behavioral Health and Primary Care Integration [ 10] and includes domains of work flow, clinical services, workspace, shared care and integration, case identification, and patient engagement. Domain scores and a total integration score are provided, along with median scores of other practices evaluated with the PIP.

Results

EHR tracking

The software program IBM SPSS for Macintosh version 23 was used to analyze data, including descriptive and inferential statistics from the initial dataset.

Demographics: Patient demographics and tracking outcomes were collected from the EHR during the initial 9-month pilot test of the FMBH program. The pilot included 188 initial new patient contacts and 80 patient followup visits with a BHC. The age of the patients ranged from 15 to 83 years, with a mean age of 44.54 years (standard deviation 15.86 years). Most patients were female (68.4%).The patients’ reported race/ethnicity was 1.0% Asian, 3.2%American Indian/Alaska Native, 4.2% Hispanic/Latino, 2.6%African American, and 75.5% white (13.5% did not report their race/ethnicity).

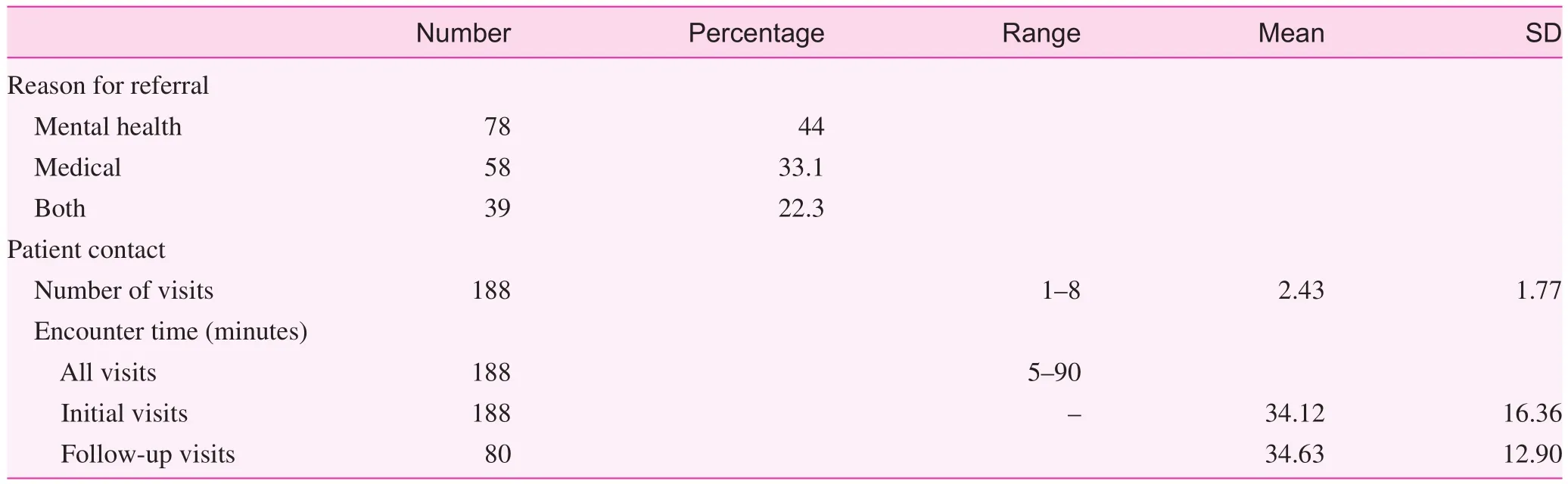

Patient contact: In terms of follow-up frequencies, patient encounters ranged from one to eight visits, including the initial warm handoff encounter. The modal number of visits was 1, with slightly under half of patients returning for at least one follow-up visit ( n = 80). The amount of contact time per visit ranged from 5 to 90 minutes, and initial visits were slightly shorter on average than follow-up visits. Initial contacts were typically completed in 15– 30 minutes versus 30 minutes for follow-up visits. See Table 1 for a further breakdown of patient contact.

Reasons for referral: Of the referrals received from primary care providers to the FMBH program, slightly under half of patients were referred primarily for mental health symptoms(e.g., anxiety, depression). Approximately one-third of patients were referred primarily for medical symptoms or behavioral medicine issues (e.g., headaches, diabetes), and the remainder of referrals included requests to address both mental and physical health issues. See Table 2 for a further breakdown of the reasons for referral.

Table 1. Patient contact and reason for referral

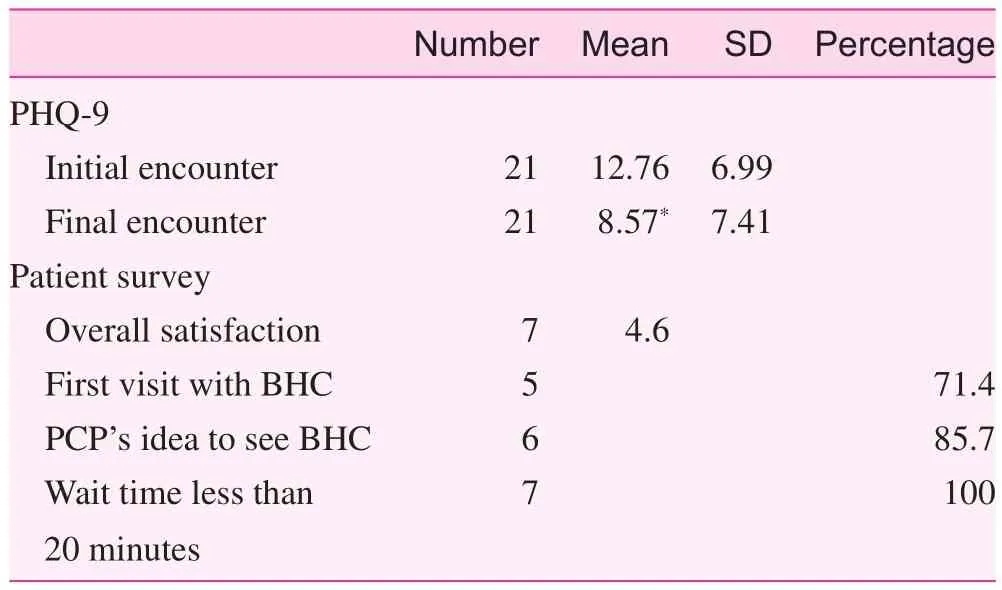

Table 2. Patient survey and clinical outcomes

Initial patient outcomes: PHQ-9: Of the 21 initial patients who completed the PHQ-9 at both the initial encounter and the final encounter, 85.7% screened positive for major depressive disorder on the PHQ-9 (a score of 5 or more in the previous 2 weeks). Of these patients, the mean total PHQ-9 scores represented a statistically significant decrease between assessments( t20= 2.82, P = 0.011). These PHQ-9 score changes, although limited, indicate that patients tended to report fewer mood symptoms after being seen in the FMBH program. However,it is important to note that we did not compare these findings with those for usual care, and thus these limited results must be interpreted with caution. See Table 2 for a further breakdown of PHQ-9 scores.

Patient satisfaction

Patient feedback was requested after the initial warm handoff encounter. Of patients who responded during the pilot phase, most indicated it was their physician’ s idea to see the BHC, most indicated that it was their first time seeing a behavioral health provider, and all of the initial patient responses indicated that their wait time to see a BHC was less than 20 minutes. The initial responses suggested overall patient satisfaction with the FMBH services received following a warm handoff (average total score of 4.6 on a five-point Likert scale). Although there has been a low initial response rate for patient satisfaction following warm handoffs and there is a potential for selection bias, these initial data suggest the potential for reaching patients who would not otherwise have been seen and for patients being satisfied with the behavioral health service. See Table 2 for a further breakdown of patient survey scores.

Provider satisfaction and use

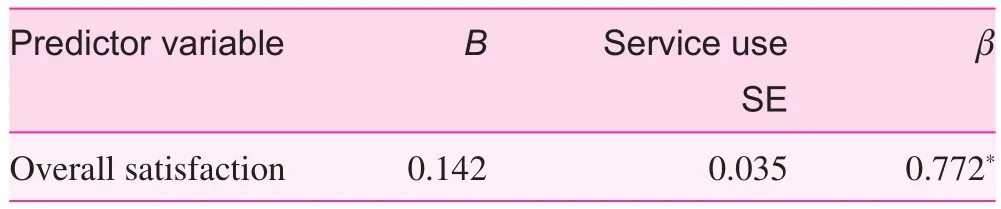

During our initial pilot phase, primary care providers( n = 13) reported using FMBH services an average of one or two times per week and providers who have used these services indicated overall satisfaction with the FMBH program(average overall satisfaction score of 4.7 on a five-point Likert scale). Regression analysis results indicated a predictive relationship between primary care providers’ satisfaction with the integrated behavioral health model and their use of these services, F(1,12) = 16.244, P = 0.002, adjusted R2= 0.56, suggesting that understanding which program components are conducive to provider satisfaction can play an important role in maximizing integrated service use (see Table 3).

Practice integration

The results of the PIP [ 9] suggest that the FMBH program is moderately integrated and scored closely to the medianof other practices. Notably lower than average development scores were obtained for case identification and patient engagement, and a notably higher than average development score was obtained for workspace, which indicated a fully developed level of integration within the FMBH program in terms of shared practice workspace.

Table 3. Summary of results of linear regression for provider satisfaction and use of Family Medicine– Behavioral Health program services

Discussion

Despite limited resources, we were able to pilot a service program that has appeared to begin to meet the behavioral health service needs at the clinic. The initial findings are suggestive of provider use of and satisfaction with FMBH services,patient satisfaction with services, and clinical improvement.Practice integration findings indicate a moderate level of integration with the program so far, with shared clinic workspace being most noteworthy in regard to the level of integration.The physical proximity of the BHCs in the clinic (i.e., office space in the same wing as other providers; clinic space in the medical examination rooms) appears to be a key factor in the moderate success of the FMBH program thus far.

On the basis of our development, implementation, and initial outcomes of a novel integrated primary care– behavioral health program in our local community, it appears that the FMBH program has the potential to continue to serve an important role in addressing the behavioral health needs of the population. Interior Alaska is a rural and remote area that is largely underserved by behavioral health providers; there are limited resources to serve a relatively high need mental health population. As such, it has been a struggle to provide adequate care to behavioral health patients in this region because of the small population size and geographic remoteness. One of the bene fits of the FMBH program we have designed is its ability to provide behavioral health services to those who would otherwise go underserved. For example, there are very few resources for Medicaid patients in our community, and behavioral health patients with Medicare or Medicaid are not always able to receive services, an issue faced by many rural and underserved communities [ 11]. One of the unforeseen bene fits of piloting the FMBH program as a training model is that,because it is a training model, we have not billed for patient services and thus are able to capture a larger number of underserved patients than we anticipated.

Future directions

The initial outcomes currently presented are limited in scope and must be interpreted with caution; however, they are suggestive of the potential for promising longer-term outcomes. The next phase of our FMBH program development and implementation will include a comprehensive program evaluation. Our initial outcomes will help inform the next phase, which will include identifying and tracking specific, culturally relevant clinical health outcomes to be monitored throughout continued program implementation and evaluation (e.g., tobacco use, medication adherence, weight management, hemoglobin A1clevel). Once additional outcomes are identified, they will be added to ongoing assessment and tracking. See Table 1 for additional elements that will be included in the full FMBH program evaluation. We also plan to continue to evaluate the provider perspective in our next phase of program evaluation. Most of the current research for integrated models has focused on patient outcomes, which is understandable; however, the provider perspective is also important [ 12]. If we can better understand primary care providers’ reasons for using FMBH services, we can better address barriers (i.e., education about the model, experience with the model) that may limit use as well as enhance potential providerspecific bene fits of an integrated model. Finally, we hope to be able to demonstrate similar clinical and cost-effectiveness shown in other integrated healthcare systems [ 1] with our next phase of program evaluation. Included in our next steps is the evolution into a model that will fit into a sustainable billing system so as to capture the underserved population of patients with behavioral health service needs.

Our initial implementation data will also help provide support in the development of sustainable models from which integrated behavioral health program implementation can be guided throughout other rural regions in the United States. In addition to guiding sustainable models of integrated healthcare service delivery, the long-term program goals include implementing formalized provider training for behavioral health clinicians in the integrated healthcare model.

Suggested applications

Implementation of new service model designs can be variable depending on multiple factors, such as geographic location,need for services, the healthcare system, and the fee system.Our implementation design and initial program outcomes suggest that such models can work in small-scale settings with minimal overhead costs. In our case, it was especially helpful to have initial buy-in from the primary care providers, who helped advocate the program development to the clinic administration. We would encourage other small practices that are seeking to develop integrated primary care– behavioral health services, especially those in rural and remote settings, to consider an implementation design similar to ours.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

Kendra Campbell contributed to project conceptualization,methods, investigation, supervision, project administration,data analysis, and writing. Angel Vasquez contributed to project methods, investigation, data analysis, and writing. Loren McKnight contributed to project methods, investigation, data analysis, and writing.

Appendix A: Family Medicine– Behavioral Health program outcome tracking

*Included in initial outcome data.

**Will be included in full program evaluation.

BHC, behavioral health consultant.

Clinic-specific information Patient-specific information Provider-specific information Use of BHC services by the clinic Number of “ warm handoff” referrals*Reasons for referral*Patient access to care Wait time to see BHC**Patient follow through on outside mental health referrals**Degree of integration*Satisfaction with integrated health services**Demographic information*Health issues/diagnoses**Follow-up disposition**Type of intervention provided**Health outcomes*,**Satisfaction with model*Use of BHC services by provider*

P l e a s e c i r c l e t h e r e s p o n s e t h a t b e s t r e f l e c t s y o u r e x p e r i e n c e w i t h t h e f a m i l y m e d i c i n e– b e h a v i o r a l h e a l t h c o n s u l t a n t s.

Appendix B: Family Medicine– Behavioral Health patient satisfaction survey

Please circle the number that corresponds with your experience with the family medicine– behavioral health consultants.

Appendix C: Provider satisfaction and use survey

1. With 1 being “ not at all comfortable” and 5 being “ very comfortable,” how comfortable are you in addressing the mental health needs of your patients (without collaboration from a behavioral health provider)?

2. Please indicate your average use of Family Medicine–Behavioral Health services (a warm handoff, electronic referral, or case consultation).

Not at all (1)

Monthly or less (2)

2– 3 times per month (3)

1– 2 times per week (4)

≥ 3 times per week (5)

3. What is your primary way of contacting the Family Medicine– Behavioral Health team?

Face-to-face (1)

Telephone task (2)

Paper referral (3)

Other (4) ____________________

4. How satisfied are you with the accessibility of the Family Medicine– Behavioral Health team?

Dissatisfied (1)

Somewhat dissatisfied (2)

Neutral (3)

Somewhat satisfied (4)

Satisfied (5)

5. How satisfied are you with our response time (i.e., how long did your patient wait to be seen by the Family Medicine– Behavioral Health team)?

Dissatisfied (1)

Somewhat dissatisfied (2)

Neutral (3)

Somewhat satisfied (4)

Satisfied (5)

6. How satisfied are you with the level of collaboration/communication with the Family Medicine– Behavioral Health team?

Dissatisfied (1)

Somewhat dissatisfied (2)

Neutral (3)

Somewhat satisfied (4)

Satisfied (5)

7. How satisfied are you with observed patient outcomes following contact with the Family Medicine– Behavioral Health team?

Dissatisfied (1)

Somewhat dissatisfied (2)

Neutral (3)

Somewhat satisfied (4)

Satisfied (5)

8. How satisfied are you with the efficiency of referring your patients to the Family Medicine– Behavioral Health team?

Dissatisfied (1)

Somewhat dissatisfied (2)

Neutral (3)

Somewhat satisfied (4)

Satisfied (5)

9. How satisfied are you with the care provided for your patients by the Family Medicine– Behavioral Health team?

Dissatisfied (1)

Somewhat dissatisfied (2)

Neutral (3)

Somewhat satisfied (4)

Satisfied (5)

10. How satisfied are you with the timeliness of communication concerning your patients with the Family Medicine– Behavioral Health team?

Dissatisfied (1)

Somewhat dissatisfied (2)

Neutral (3)

Somewhat satisfied (4)

Satisfied (5)

11. How satisfied are you with medical record documentation provided by the Family Medicine– Behavioral Health team?

Dissatisfied (1)

Somewhat dissatisfied (2)

Neutral (3)

Somewhat satisfied (4)

Satisfied (5)

12. How satisfied are you with the Family Medicine–Behavioral Health services overall?Dissatisfied (1)

Somewhat dissatisfied (2)

Neutral (3)

Somewhat satisfied (4)

Satisfied (5)

13. With 1 being “ Not at all confident” and 5 being “ Very confident,” how confident are you that the Family Medicine– Behavioral Health team is equipped to care for your patients?

14. Please indicate on average how frequently you refer patients to a behavioral health provider other than the Family Medicine– Behavioral Health team.

Not at all (1)

Monthly or less (2)

2– 3 times per month (3)

1– 2 times per week (4)

≥ 3 times per week (5)

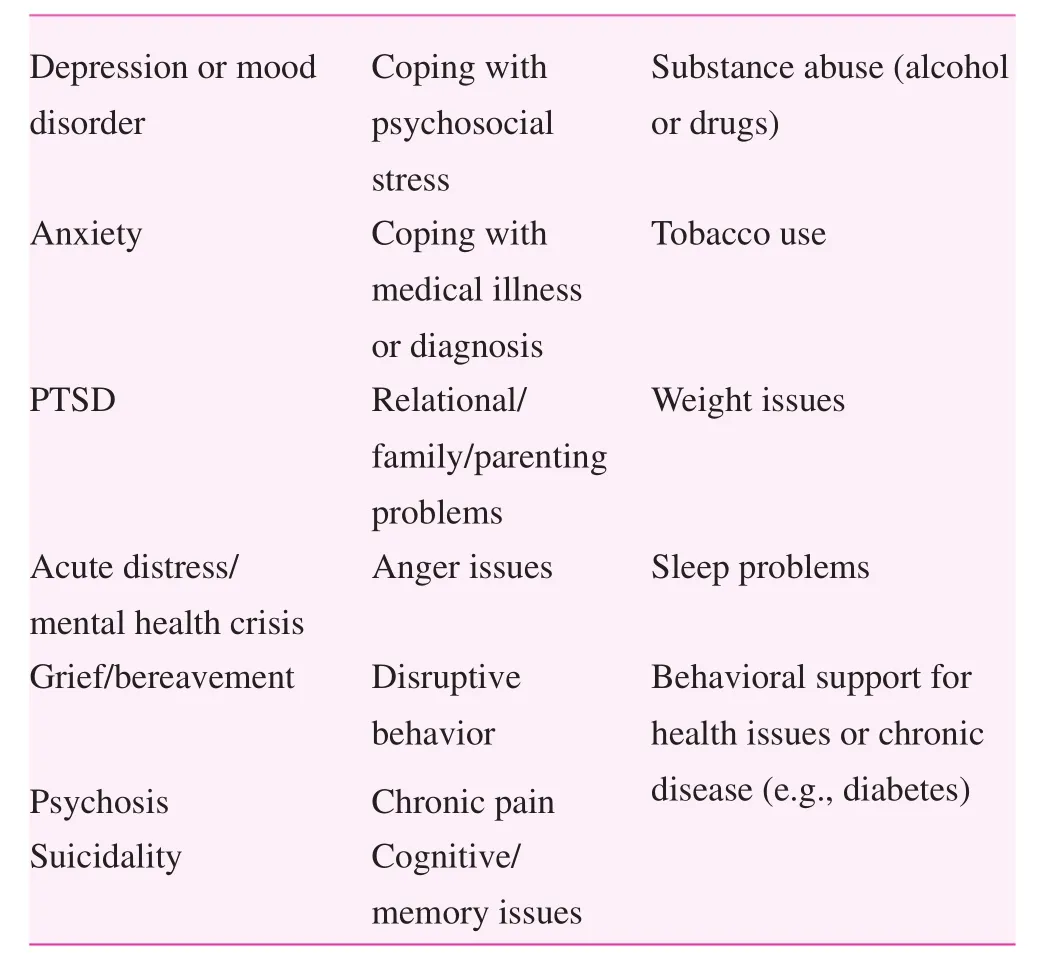

15. Below is a list of issues for which Family Medicine–Behavioral Health services could be used. Please indicate which patient issues you have used the Family Medicine– Behavioral Health team for help with,through consultation, warm handoff, or referral (check all that apply).

D e p r e s s i o n o r m o o d d i s o r d e r C o p i n g w i t h p s y c h o s o c i a l s t r e s s S u b s t a n c e a b u s e (a l c o h o l o r d r u g s)A n x i e t y C o p i n g w i t h m e d i c a l i l l n e s s o r d i a g n o s i s T o b a c c o u s e P T S D R e l a t i o n a l/f a m i l y/p a r e n t i n g p r o b l e m s W e i g h t i s s u e s A c u t e d i s t r e s s/m e n t a l h e a l t h c r i s i s A n g e r i s s u e s S l e e p p r o b l e m s G r i e f/b e r e a v e m e n t D i s r u p t i v e b e h a v i o r P s y c h o s i s C h r o n i c p a i n S u i c i d a l i t y C o g n i t i v e/m e m o r y i s s u e s B e h a v i o r a l s u p p o r t f o r h e a l t h i s s u e s o r c h r o n i c d i s e a s e (e.g., d i a b e t e s)

Family Medicine and Community Health2018年3期

Family Medicine and Community Health2018年3期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Number, distribution, and predicted needed number of general practitioners in China*

- The role of the teaching practice in undergraduate medical education:A perspective from the United States of America

- A cross-sectional study to assess the out-of-pocket expenditure of families on the health care of children younger than 5 years in a rural area

- Blood pressure– controlling behavior in relation to educational level and economic status among hypertensive women in Ghana

- Development and validation of the Mothers of Preterm Babies Postpartum Depression Scale

- Factors influencing IOP changes in postmenopausal women