利福昔明对SIBO+腹泻型肠易激综合征患者NF-κB及炎性因子的影响

刘治宏,崔立红

小肠细菌过度生长(small intestinal bacterial overgrowth,SIBO)是一种肠道微生物失调的表现,具体以近端小肠分泌物菌落数≥105cfu/ml,小肠细菌过量或菌群失衡为特征[1-2]。肠易激综合征(irritable bowel syndrome,IBS)是一种慢性胃肠道疾病[3],其特征是在没有已知器官病理性改变的情况下出现排便习惯紊乱和腹痛等症状,在西方国家发病率约为10%[4-5]。按照患者症状,IBS可分为便秘型(IBS-C)、腹泻型(IBS-D)、混合型(IBS-A)和未定型(IBS-U),其中以IBS-D最常见,约占40%[6-8]。超过25%的排便为布里斯托分类的6或7型,并且少于25%的排便为1或2型[9]可诊断为IBS-D。SIBO与IBS-D关系密切,IBS患者有更高的SIBO患病率[10]。本课题组前期已证明TLR4/NF-κB通路在IBS-D大鼠模型中的作用,其具体机制可能是通过促进炎性因子的释放而影响肠道菌群。本研究观察利福昔明治疗后IBS-D患者核因子κB(nuclear factor κB,NF-κB)及炎性因子的变化,以期进一步明确IBS-D的发病机制。

1 资料与方法

1.1 一般资料 选取2016年6月-2017年12月于海军总医院进行甲烷和氢气呼气试验(SIBO阳性)的IBS-D患者(满足罗马Ⅲ标准)78例,随机分成试验组与对照组(n=39)。试验组男18例,女21例,年龄37.7±9.8岁;对照组男16例,女23例(后脱失2例),年龄38.0±9.5岁。两组男女比例、年龄等差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。排除标准:①肝脏病变、急性感染、其他慢性炎性疾病及妊娠患者;②在试验开始前1个月内使用抗生素和益生菌的患者;③糖尿病患者[11];④长期使用质子泵抑制剂、慢性萎缩性胃炎的患者[12];⑤肥胖患者[13]。本研究经海军总医院伦理委员会审核通过,所有患者均签署知情同意书。

1.2 甲烷和氢气呼气试验 本试验采用甲烷和氢气呼气试验[14]检测SIBO。受检者口服底物前漱口,而后向采气袋内吹入气体,30min后服用乳果糖10ml。每隔30min重复上述步骤采气,直至收集完8个采气袋。检测由甲烷和氢气检测工作站(美国Quintron公司)完成。检查注意事项:空腹8h以上接受检查,整个过程禁食,可饮水;晨起后禁止吸烟;检测过程中不做剧烈运动。

1.3 SIBO诊断标准 ①氢气浓度>基础值20ppm;②甲烷浓度升高>基础值12ppm;③甲烷和氢气浓度之和升高>基础值15ppm;④整个检查过程中出现双峰曲线。

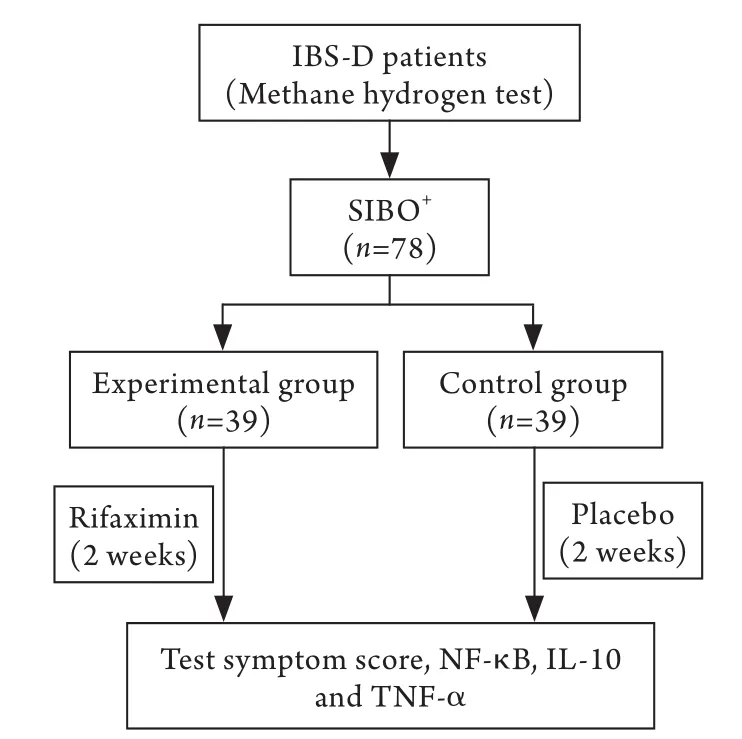

1.4 分组及治疗 所有参与试验患者均被要求试验前1个月及实验过程中不服用任何已知的可以改变胃肠功能、缓解疼痛的药物以及精神类药品。试验开始前完善症状评分并检测白细胞介素-8(interleukin-8,IL-8)、肿瘤坏死因子α(tumour necrosis factor-α,TNF-α)、NF-κB等指标。试验组给予利福昔明治疗(0.2g/次,4次/d,共2周,意大利ALFA WASSERMANN制药公司);对照组给予安慰剂治疗2周。再次进行症状评分并检测上述指标。治疗前对患者进行饮食、生活方式等的指导。试验流程如图1所示。

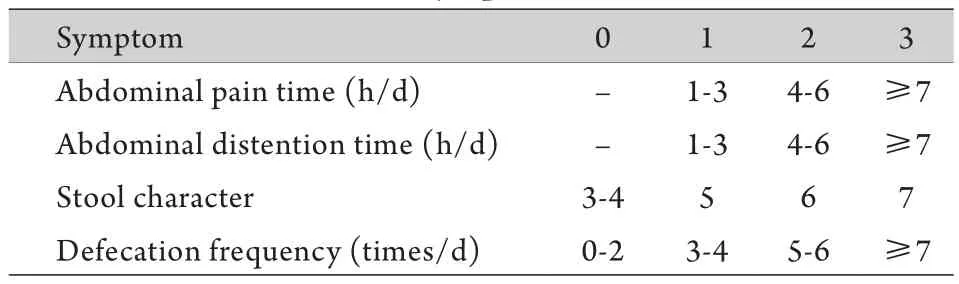

1.5 IBS-D症状评分 治疗前及治疗后1周,分别记录两组如表1[15]所示的症状及频率,并计算每日评分,最后计算治疗前及治疗后1周的平均评分。大便性状评分参考Bristol分型[16]。

图1 试验流程图Fig.1 Experimental flow graph

表1 IBS-D症状评分表[15]Tab.1 IBS-D symptom score table[15]

1.6 血清IL-8、TNF-α、NF-κB等指标检测 采集清晨空腹12h静脉血3ml,离心后存放于–80℃冰箱备用。检测试剂盒由北京亿鸣生物有限公司提供。

1.7 统计学处理 采用SPSS 22.0软件进行统计分析。计量资料以±s表示,组间及治疗前后比较采用t检验。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结 果

2.1 两组IBS-D患者治疗前后症状评分比较 对照组给予安慰剂,并进行健康饮食生活宣教,治疗前后症状评分比较差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。试验组治疗前后评分比较差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。试验组IBS各症状改善在治疗后优于对照组(P<0.05,表2)。

2.2 两组IBS-D患者治疗前后IL-8、TNF-α、NF-κB比较 对照组治疗前后各指标差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。试验组治疗后IL-8、TNF-α、NF-κB较治疗前明显下降,差异均有统计学意义(表3)。

3 讨 论

IBS-D是一种常见的功能性肠病,其具体发病机制尚不清楚,目前临床上主要采用对症治疗。有文献报道在IBS的大鼠模型中,TLR4通过NF-κB信号通路对内脏敏感性造成影响[17]。本课题组前期通过IBS-D大鼠模型发现TLR4/NF-κB信号通路在IBS-D的发病中发挥作用。

表2 两组IBS-D患者治疗前后症状评分比较(±s)Tab. 2 Comparison of symptom scores before and after treatment between two groups (±s)

表2 两组IBS-D患者治疗前后症状评分比较(±s)Tab. 2 Comparison of symptom scores before and after treatment between two groups (±s)

(1)P<0.05 compared with pre-treatment; (2)P<0.05 compared with control group

Item Control group (n=37) Experimental group (n=39)Pre-treatment Post-treatment Pre-treatment Post-treatment Abdominal pain time (h/d) 1.65±0.63 1.57±0.60 1.67±0.66 0.69±0.52(1)(2)Abdominal distention time (h/d) 1.95±0.74 1.84±0.73 1.97±0.78 1.41±0.75(1)(2)Stool character 1.92±0.76 1.81±0.74 1.95±0.76 1.36±0.63(1)(2)Defecation frequency (times/d) 1.65±0.63 1.57±0.55 1.54±0.60 0.97±0.67(1)(2)

表3 两组IBS-D患者治疗前后NF-κB、炎性因子比较(±s)Tab. 3 Comparison of NF-κB and inflammatory factors before and after treatment between two groups (±s)

表3 两组IBS-D患者治疗前后NF-κB、炎性因子比较(±s)Tab. 3 Comparison of NF-κB and inflammatory factors before and after treatment between two groups (±s)

(1)P<0.05 compared with pre-treatment; (2)P<0.05 compared with control group

Group TNF-α(pg/ml) NF-κB(ng/ml) IL-8(pg/ml)Pre-treatment Post-treatment Pre-treatment Post-treatment Pre-treatment Post-treatment Control group 10.33±3.03 10.18±3.08 1.17±0.23 1.12±0.24 18.49±8.08 17.55±7.89 Experimental group 10.13±2.93 8.22±2.20(1)(2) 1.12±0.19 0.98±0.15(1)(2) 17.25±7.04 11.12±4.61(1)(2)

SIBO与IBS-D关系密切。研究显示,SIBO可导致营养吸收不良和肠道炎症[18],肠道的低度炎症也是IBS的发病机制之一[19-20]。Ahn等[21]发现,IBS-D患者肠黏膜免疫细胞计数较高。Peralta等[22]发现,根除SIBO后有75%的IBS患者症状缓解。Mizutani等[23]指出,轻微的炎症也可以导致胃肠道神经、平滑肌功能的持续变化。Rhee等[24]的研究显示,肠道菌群可调节肠道运动、分泌,反之,肠道运动又可能影响菌群。SIBO不仅仅是肠道蠕动改变的结果,也会导致肠道蠕动发生改变[25]。肠道炎症和SIBO激活的免疫应答均可引起细胞因子失衡[23]。David等[26]通过检测钙卫蛋白明确肠道炎症情况,发现SIBO阳性的IBS患者比阴性患者有更高的肠道炎症。IBS/SIBO与肠道炎症的关系如图2所示。

图2 IBS/SIBO与肠道炎症的关系图Fig.2 The relationship between IBS/SIBO and intestinal inflammation

利福昔明是一种不易吸收的口服抗生素,具有良好的安全性,对于旅行者腹泻、功能性腹胀、肠易激综合征和SIBO等都有较好的疗效[27]。利福昔明降低IL-8、TNF-α、NF-κB的机制可能是直接的杀菌、抑菌作用,减弱局部炎症[28]。Hoffman等[29]认为利福昔明能够降低SIBO患者的肠道通透性,抑制细菌穿透黏膜,进而稳定肠道菌群。Giuseppe等[30]发现在Caco-2细胞中,利福昔明可通过孕烷X受体(pregnane X receptor,PXR)抑制TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB,进而抑制炎症。另外也有文献报道,在结肠炎模型中利福昔明可作用于人PXR,进而抑制NF-κB的表达[31]。Mencarelli等[32]认为在肠上皮细胞中利福昔明无法阻止TNF-α抑制PXR表达的过程,也不能使肠道活检的炎性组织PXR表达上调,所以利福昔明在炎症反应中是增强PXR的活性而不是增加其表达。

本研究应用利福昔明治疗SIBO+的IBS-D患者,发现根除SIBO后,患者NF-κB、IL-8、TNF-α等均下降(IL-8、TNF-α均为促炎性细胞因子,在炎症中起关键作用[33]),部分IBS-D患者症状明显改善,从而提示SIBO可能导致NF-κB升高,进而加重IBS-D症状。但是本试验也存在一些不足之处,如未进一步检测黏膜的炎性因子,未设置SIBO-对照组等,下一步须进一步完善实验。

总之,本研究结果表明,SIBO阳性的IBS-D患者经利福昔明治疗后,血清IL-8、TNF-α和NF-κB水平以及IBS症状评分显著下降,提示SIBO可能通过NF-κB影响炎性因子及IBS-D患者的症状,进一步阐明了SIBO与IBS-D的关系及IBS-D发病机制。另外利福昔明作为一种新型抗生素,对IBS-D合并SIBO阳性患者有较好疗效。

[1] Ghoshal UC, Gwee KA. Post-infectious IBS, tropical sprue and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: the missing link[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2017,14(7): 435-441.

[2] Shah A, Shanahan E, Macdonald GA, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in chronic liver disease[J]. Semin Liver Dis, 2017, 37(4): 388-400.

[3] Zhang JY, Huang YX, Qin M, et al. そe relation of Cx43 and NMDA to visceral sensitization in rats with irritable bowel syndrome[J].Med J Chin PLA, 2015, 40(12): 946-949. [张静瑜, 黄裕新, 秦明,等. Cx43、NMDA与大鼠肠易激综合征内脏敏化的关系研究[J]. 解放军医学杂志, 2015, 40(12): 946-949.]

[4] Weaver KR, Melkus GD, Henderson WA. Irritable bowel syndrome[J]. Am J Nurs, 2017, 117(6): 48-55.

[5] Corsetti M, Whorwell P. The global impact of IBS: time to think about IBS-specific models of care?[J]. Therap Adv Gastroenterol, 2017, 10(9): 727-736.

[6] Defrees DN, Bailey J. Irritable bowel syndrome: epidemiology,pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment[J]. Prim Care, 2017,44(4): 655-671.

[7] Xu XJ, Liu L, Yao SK. Nerve growth factor and diarrheapredominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D): a potential therapeutic target?[J]. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B, 2016, 17(1): 1-9.

[8] Fragkos KC. Spotlight on eluxadoline for the treatment of patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea[J]. Clin Exp Gastroenterol, 2017, 10: 229-240.

[9] Mearin F, Lacy B, Simrén M. Bowel disorders[J].Gastroenterology, 2016, pii: S0016-5085(16)00222-5.

[10] Ghoshal UC, Shukla R, Ghoshal U. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and irritable bowel syndrome: a bridge between functional organic dichotomy[J]. Gut Liver, 2017, 11(2): 196-208.

[11] Zhao M, Liao D, Zhao J. Diabetes-induced mechanophysiological changes in the small intestine and colon[J]. World J Diabetes,2017, 8(6): 249-269.

[12] Fujimori S. What are the effects of proton pump inhibitors on the small intestine?[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2015, 21(22):6817-6819.

[13] Roland BC, Lee D, Miller LS, et al. Obesity increases the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)[J].Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2018, 30(3): doi: 10.1111/nmo.13199.

[14] Grace E, Shaw C, Whelan K, et al. Review article: small intestinal bacterial overgrowth--prevalence, clinical features, current and developing diagnostic tests, and treatment[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2013, 38(7): 674-688.

[15] Abbas Z, Yakoob J, Jafri W, et al. Cytokine and clinical response to Saccharomyces boulardii therapy in diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized trial[J]. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2014, 26(6): 630-639.

[16] Thabit AK, Nicolau DP. Lack of correlation between bristol stool scale and quantitative bacterial load in clostridium difficile infection[J]. Infect Dis (Auckl), 2015, 8: 1-4.

[17] Yuan B, Tang WH, Lu LJ, et al. TLR4 upregulates CBS expression through NF-kappaB activation in a rat model of irritable bowel syndrome with chronic visceral hypersensitivity[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2015, 21(28): 8615-8628.

[18] Moraru IG, Portincasa P, Moraru AG, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth produces symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome which are improved by rifaximin. A pilot study[J].Rom J Intern Med, 2013, 51(3-4): 143-147.

[19] Bashashati M, Rezaei N, Shafieyoun A, et al. Cytokine imbalance in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and metaanalysis[J]. Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2014, 26(7): 1036-1048.

[20] Barbara G, Cremon C, Stanghellini V. Inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: similarities and differences[J]. Curr Opin Gastroenterol, 2014, 30(4): 352-358.

[21] Ahn JY, Lee KH, Choi CH, et al. Colonic mucosal immune activity in irritable bowel syndrome: comparison with healthy controls and patients with ulcerative colitis[J]. Dig Dis Sci,2014, 59(5): 1001-1011.

[22] Peralta S, Cottone C, Doveri T, et al. Small intestine bacterial overgrowth and irritable bowel syndrome-related symptoms:experience with Rifaximin[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2009,15(21): 2628-2631.

[23] Mizutani T, Akiho H, Khan WI, et al. Persistent gut motor dysfunction in a murine model of T-cell-induced enteropathy[J].Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2010, 22(2): 196-203, e65.

[24] Rhee SH, Pothoulakis C, Mayer EA. Principles and clinical implications of the brain-gut-enteric microbiota axis[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2009, 6(5): 306-314.

[25] Wu WC, Zhao W, Li S. Small intestinal bacteria overgrowth decreases small intestinal motility in the NASH rats[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2008, 14(2): 313-317.

[26] David L, Babin A, Picos A, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is associated with intestinal inflammation in the irritable bowel syndrome[J]. Clujul Med, 2014, 87(3): 163-165.

[27] Shayto RH, Abou MR, Sharara AI. Use of rifaximin in gastrointestinal and liver diseases[J]. World J Gastroenterol,2016, 22(29): 6638-6651.

[28] Lacy BE, Moreau JC. Diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: Diagnosis, etiology, and new treatment considerations[J]. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract, 2016, 28(7): 393-404.

[29] Hoffman JT, Hartig C, Sonbol E, et al. Probable interaction between warfarin and rifaximin in a patient treated for small intestine bacterial overgrowth[J]. Ann Pharmacother, 2011,45(5): e25.

[30] Esposito G, Nobile N, Gigli S, et al. Rifaximin improves clostridium difficile toxin a-induced toxicity in caco-2 cells by the PXR-dependent TLR4/MyD88/NF-kappaB pathway[J].Front Pharmacol, 2016, 7: 120.

[31] Esposito G, Gigli S, Seguella L, et al. Rifaximin, a non-absorbable antibiotic, inhibits the release of pro-angiogenic mediators in colon cancer cells through a pregnane X receptor-dependent pathway[J]. Int J Oncol, 2016, 49(2): 639-645.

[32] Mencarelli A, Migliorati M, Barbanti M, et al. Pregnane-X-receptor mediates the anti-inflammatory activities of rifaximin on detoxification pathways in intestinal epithelial cells[J].Biochem Pharmacol, 2010, 80(11): 1700-1707.

[33] Seyedmirzaee S, Hayatbakhsh MM, Ahmadi B, et al. Serum immune biomarkers in irritable bowel syndrome[J]. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol, 2016, 40(5): 631-637.