Functional outcomes and health-related quality of life after open repair of rotator cuff tears: a prospective cohort study

Joel Galindo-Avalos , Oscar Medina-Pontaza Juan López-Valencia Juan Manuel Gómez-Gómez Avelino Colin-VázquezRubén Torres-González

1 Department of Orthopedics and Trauma Surgery, UMAE “Dr. Victorio de la Fuente Narváez” IMSS-UNAM. Ciudad de México, México

2 Health Education and Research Division, UMAE “Dr. Victorio de la Fuente Narváez” IMSS, Delegación Gustavo A. Madero, México

INTRODUCTION

Background

The incidence of shoulder pain in the general population is at around 11.2/1,000 patients per year, with rotator cuff tears being the most common cause of shoulder pain. The estimated incidence of rotator cuff tears is 3.7/100,000 cases per year with a higher peak at thefifth decade of life in men and at the sixth in women.1Rotator cuff tears have an impact on patient impairment and quality of life that is comparable to that of diabetes,myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure or depression.2

Surgical treatment should be directed to decompressing and repairing the torn rotator cuff as best as possible.3Symptomatic patients typically describe pain with overhead tasks and pain with daily activities.4The diagnosis must be both clinical and radiographic; radiographic studies include ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and arthro-MRI.5,6

Coefield and DeOrio classified rotator cuff tears depending on the size of the tear, dividing them into small (less than 1 cm), medium (1–3 cm), large (3–5 cm) and massive (more than 5 cm).6-8In 2006, Burkhart classified rotator cuff tears depending on its patterns: crescent-shaped, U-shaped, and massive, contracted, immobile tears.9

In the United States, about 300,000 rotator cuff repair surgeries are performed annually. Surgery can be performed using open or arthroscopic approaches, but there has recently been a dramatic increase in the number of patients treated arthroscopically. Purported advantages of arthroscopy include rapid recovery and decreased morbidity, however, in the developing countries, the high price of the instruments and devices used for an arthroscopic approach makes it necessary to continue the traditional open repair of rotator cuff tears.4,8Since originally described by Neer in 1972, acromioplasties have become one of the most commonly performed procedures in orthopedic surgery. The most common indication for subacromial decompression remains subacromial impingement with or without a concomitant rotator cuff tear.10

Functional outcomes after rotator cuff surgery are evaluated using a variety of instruments; however, the overall health status,or quality of life, after rotator cuff repair cannot be adequately assessed by these instruments. Despite the recognized importance of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) assessment, few studies on HRQoL after rotator cuff repair have been reported.11In 2002, the a shortened form (12 items) of the Short Form 36 Health Survey version 2 (SF12v2) was published, a shorter version of the SF-36 questionnaire, one of the most widely used tools for assessing quality of life. The main strategy for the interpretation of these questionnaires is based on the use of reference population norms. These norms indicate a standard value that facilitates the interpretation of the questionnaire scores over those expected for their age group and sex.12

The American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES)Research Committee developed in 1994, a standard method for evaluating shoulder function.13In 2002, a modification to this scale was validated, which must befilled only by the patient, and it consists of 2 dimensions: pain and activities of daily living. The pain score and function composite score are weighted equally (50 points each) and combined for a total score out of a possible 100 points.14

The ultimate goal in rotator cuff surgery is to improve patient-reported results including HRQoL, shoulder function and to restore cuff integrity. Worldwide, orthopedic surgeons prefer to treat rotator cuff tears arthroscopically, despite it being more expensive and having a higher learning curve than open repair, arguing that open repair is not as effective as arthroscopic repair. The goal of this paper is to prove that open repair could yield good functional results and improve a patient’s quality of life by applying two questionnaires including ASES scores and SF12v2 surveys, which has certain guiding significance in clinical orthopedics.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Patients

One hundred and twenty patients (35 males and 85 females)aged 40 to 65 years, who were diagnosed with subacromial impingement associated with a rotator cuff tear and who were treated by open surgical repair in the period from February 2016 to April 2016, were included.

Patients who did not sign informed consent and fall into the age range, and had previous glenohumeral dislocation, a previous neurological lesion of the shoulder or a previous surgery on the affected shoulder were excluded from the study. Patients who had a massive rotator cuff tear and surgery-related complications during the time of the study were removed from the study.

Patients admitted to the Reconstructive Joint Surgery Department at our hospital who had a diagnosis of a rotator cuff tear and were scheduled for open subacromial decompression and tear repair, and who met the inclusion criteria were identified.

Surgery

Patients were brought to the operating room and wereplaced under general anesthesia and positioned in the beach-chair position. The shoulder was examined underanesthesia and then it was properly draped.

The rotator cuff was exposed through a modified Robert’s approach to the acromioclavicular (AC) joint. A Mumford clavicle osteotomy was performed if there was any AC osteoarthrosis. The deltoid was split and dissected off the acromion and an anterior acromioplasty was performed as described by Neer.3The cuff was mobilized byfirst releasing subacromial adhesions and then transecting the coracohumeral ligament andfinally intra-articular adhesions as required.

Strengths and limitations

The cuff was then repaired in a tendon-tendon fashion using No. 5 nonabsorbable sutures. If necessary, a bone trough was then made at the footprint of the rotator cuff. No. 5 nonabsorbable sutures were placed in the rotator cuff, using a locking suture pattern, and then passed through the trough and tied over a bone bridge on the lateral humeral cortex.The incision was irrigated with saline to ensure proper hemostasis. The deltoid was reattached to the acromion using No. 3 nonabsorbable sutures. The incision was then closed with a standard technique.

Size and pattern of the rotator cuff tear were assessed in a standardized fashion for all patients and classified according to the Coefield and Burkhart classifications respectively.7,9

Postoperative treatment and follow-up

After surgery, all patients were placed in a shoulder sling for 2 weeks and were referred for physical therapy, commencing 2 weeks after surgery, using a standardized protocol.

During thefirst 6 weeks, only self-assisted ROM (excluding abduction) and pendular exercises of the shoulder were permitted. In addition, exercises emphasizing theisometric recruitment of scapular stabilization musculature were initiated. Active ROM exercises of the elbow, wrist, and hand were also performed.

From 6 to 10 weeks postoperatively, active shoulder ROM and self-assisted stretching toward end range were added to the program. Scapular stabilization exercises were progressed, and closed chain strengthening exercises were added to the program.

Questionnaire survey and data collection

The day before the surgery, informed consent was signed by the patients, and preoperative SF12v212and ASES13surveys were applied by one of the authors. Shoulder function was categorized as excellent (88–100), good (75–87), regular(62–74), or bad (61 or less) depending on the ASES score.Data collected in the SF12v2 survey was analyzed using the QualityMetric Health Outcomes™ Scoring Software 4.5(QualityMetric Inc., Lincoln, RI, USA). Results were categorized as above the norm, at the norm or under the norm in the physical component summary (PCS) and in the mental component summary (MCS).

When the patients were discharged from the hospital, three follow-up surveys were performed at 3, 6 and 12 months after their surgery through a phone call.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive and inferential analyses were performed usingIBM® SPSS® Statistics 23.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY,USA). The differences in the categorical variables (affected side, tear size and tear pattern, functional category and HRQoL category) were analyzed using the chi-square test. The differences in ASES and SF12v2 scores between preoperative and postoperative 3, 6 and 12 months follow-up were analyzed using the Student's t-test for paired samples. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient’s entry study and follow-up

In the evaluated period from February 1stto April 28th, 2016, a total of 204 subacromial decompression and rotator cuff repair procedures by an open technique were performed in patients diagnosed with subacromial impingement and rotator cuff tear;of the 204 patients, 55 were older than 65 years and 13 of them were younger than 40 years, so they were left out of the study.

Informed consent was obtained from 136 patients and the preoperative ASES and SF12v2 surveys were applied. Thirteen of these patients had massive rotator cuff tears as a surgicalfinding, and 3 developed adhesive capsulitis as a postoperative complication, so they were removed from the study.

Demographics

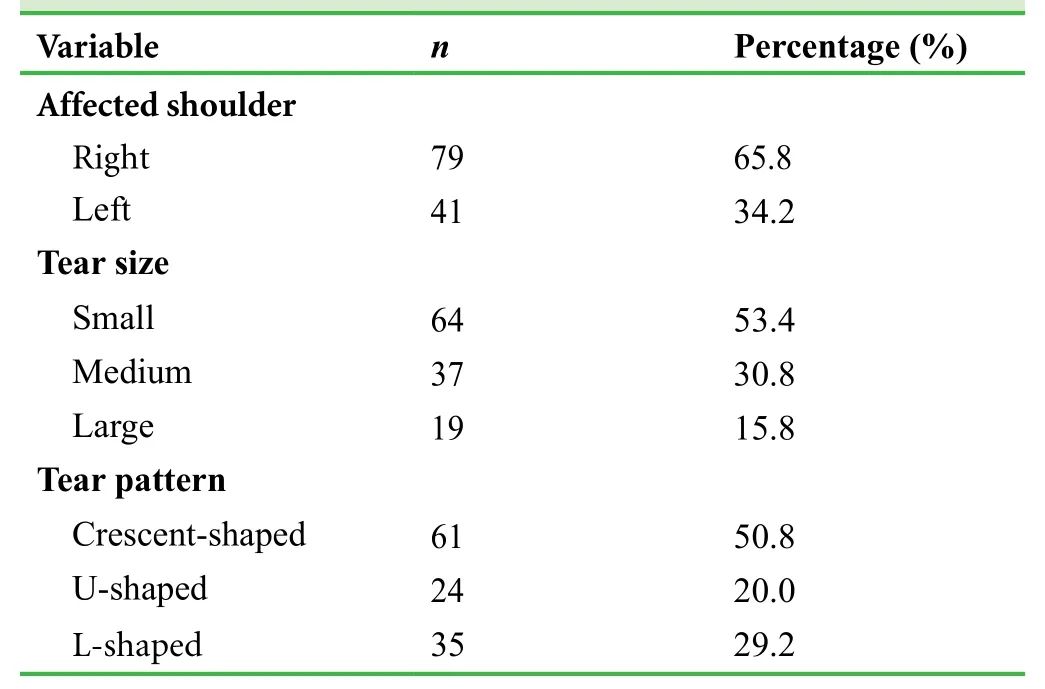

From thefinal sample of 120 patients, we observed a majority of women, representing 70.8% (85 patients); and men representing 29.2% (35 patients), with a mean age of 54 years. The most affected side was the right side, the most common tear size was the small one, and the most common tear pattern was the crescent-shaped one (Table 1).

Table 1: Surgical characteristics of all patients

Functional outcomes

As for shoulder function, we found that nearly 100% of patients had a bad shoulder function preoperatively. At the 3 months follow-up, 65% of patients had a bad shoulder function, 34.25% a fair one, and only 0.8% a good one. At the 6 months follow-up, 53.3% of the patients had a good shoulder function, 45.8% an excellent one, and only 0.8% a fair one.At thefinal follow-up 97.5% of the patients had an excellent shoulder function and only 2.5% had a good shoulder function.

SF12v2 survey results

As for HRQoL, the results from the SF12v2 survey were divided by the software into the PCS and the MCS; furthermore,the PCS was divided into four categories, which are physical functioning (PF), role physical (RP), bodily pain (BP) and general health (GH); the MCS was also divided into four categories, which are Vitality (VT), Social Functioning (SF),Role Emotional (RE) and Mental Health (MH); the results of the surveys are shown in Figure 1.

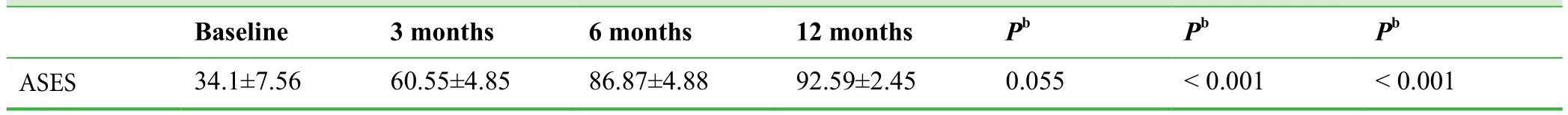

Secondary analysis results

When secondary analysis was performed, we found a statistically significant difference between the preoperative ASES score with the 6 and 12 months follow-up results (Table 2);between preoperative PCS with the 6 and 12 months follow-up;and between preoperative MCS with the 12 months follow-up(Table 3) (P < 0.05). We found no correlation between the Functional category with the HRQoL PCS and MCS category in any of the evaluated periods; we found no correlation between sex, affected side, tear size, and tear pattern with the Functional category or the HRQoL PCS and MCS category in any of the evaluated periods (Table 4) (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The goal of rotator cuff surgery is to improve patient’s quality of life through pain reduction and improvement in shoulder function. The primary goal of our study was to determine the effectiveness of the open surgical technique in the aforementioned clinical outcomes, and our results are mostly consistent with those reported by the international literature.

Zhaeentan et al.15conducted a retrospective study in which 73 patients, with a mean age of 59 years, similar to our study;who had a rotator cuff tear that was surgically repaired by an open technique were evaluated,finding that 87% of thepatients reported to be very satisfied with their result, with a follow-up time that ranged from 14 to 149 months.

Goutallier et al.16conducted a retrospective study with a total of 30 patients with a rotator cuff tear that was repaired by an open technique, who had a mean age of 67 years, with an average follow-up time of 8.9 years. Patients were evaluated using the Constant scale, showing an initial mean score of 51.9 points, and afinal score of 76.8. They found no correlation between the score with the degree of fatty degeneration.Unlike our study, this one showed a better initial score, and a worsefinal score.

Clavert et al.17conducted a retrospective evaluation of 24 patients with rotator cuff tear, of whom 14 were treated by a subacromial decompression, acromioplasty and open repair of the tear. They had a mean follow-up time of 8.2 years, with a mean preoperative constant score of 63.5 and 81.63 postoperative, withoutfinding a correlation between the age and gender with the Constant scores. As in our study, there was no correlation between age and gender with the functional outcome;unlike our study, the range between the scores was lower, the follow-up period was longer, and the sample was smaller.

Papadopoulos et al.18evaluated the functional outcome of 27 shoulders with rotator cuff tear repaired by an open technique with the UCLA and Constant scales, with a mean follow-up of 40.2 months, reporting excellent results in 71% of the patients, good in 22% and regular in 7% of them using the UCLA scale; with the Constant scale, 67% of the patients had excellent results, 26% good and 7% regular. As in our study,no correlation was found between tear size and functional outcomes; however, our study reported excellent results in 97.5% of patients at 12 months.

Figure 1: Preoperative (A) and postoperative 3- (B), 6-month (C), and 1-year (D) health-related quality of life scores.

Table 2: ASES scores measured over time a

Hanusch et al.19conducted a prospective study with a sample of 24 patients with large or massive rotator cuff tears, with a mean age of 60 years. Patients were evaluated using the Constant scale,finding a preoperative mean score of 36 points,and postoperative mean score of 68 points. Unlike our study,this study showed a lower functional outcome, however, our study did not evaluate massive rotator cuff tears, which is already reported as a risk factor for poor functional outcome.20

Vastamäki et al.21conducted a retrospective study in which 416 patients with a rotator cuff tear repaired by an open technique were evaluated over a 16-year period,finding that 88 patients developed a postoperative frozen shoulder that required a new intervention; this incidence is much higher than in our study, however, our follow-up time and sample size are lower, which may explain these differences.

Table 4: Relationship beetween categorical variables

Mejía-Salazar et al.22conducted a study comparing the functional outcomes obtained between open and arthroscopic repair of rotator cuff tears with a focus on supraspinatus tear.A total of 32 patients underwent open repair, with a majority of women, with a mean age of 61 years and a mean follow-up time of 68 weeks, as in our study, the right shoulder was the most affected. They found a better functional outcome in the arthroscopic group; however, the total scores for each group are not reported, making it impossible to compare with our study.

Connelly et al.23conducted a retrospective study evaluating the quality of life and functional outcomes of patients with massive rotator cuff tears. The total sample consisted of 22 patients, predominantly male, with a mean age of 62.6 years and a mean follow-up time of 14 months. The Constant and Oxford scales were used to assess shoulder function,finding good results in 68% of the patients. The SF12 was used to assess quality of life,finding that in the physical and emotional component the patients were below the norm, but vitality and mental health were above the norm. Unlike our study,these authors reported a predominance of males, with lower functional and quality of life scores, which can be explained by the fact that they only studied massive rotator cuff tears,which were excluded from our study.

Baysal et al.24conducted a cohort study similar to ours, with a sample of 88 patients, with a follow-up time of up to 5 years,to assess the quality of life and functional outcomes after open rotator cuff repair. In this study they used the ASES scale for functional evaluation (as well as our study), in addition to the Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index (WORC). The mean age of the patients was 54 years. They found 35% of small tears, 42%medium tears and 11% large tears. Regarding the ASES scale, they found a mean preoperative score of 55.4, and 90.6 at 12 months,similar to our study. Regarding quality of life, 96% of the patients reported to be very satisfied or satisfied, while 3% reported to be fairly satisfied and 1% not satisfied. As in our study, no correlation was found between tear size with functional outcomes and quality of life. Unlike our study, all patients were submitted to the same rehabilitation protocol after surgery.

Saraswat et al.20conducted a 10-year follow-up study of Baysal's cohort,24finding that, at 10 years, the functional outcome and health related quality of life remained similar,although some of the patients were lost at follow-up.

CONCLUSION

Open repair of rotator cuff tears remains a valid and effective option, despite the current trend of arthroscopic repair,obtaining satisfactory results at around 6 months after surgery.

To our knowledge, this is thefirst study that seeks the correlation of the tear pattern with the functionality and the quality of life, although no correlation was found. We consider that the improvement of pain is the most important part for obtaining the results reported in this study. Finally,we also consider that there is an opportunity to perform a better study, in which open and arthroscopic repairs are compared, in which the repair method used (tendon-tendon,bone-tendon, and anchor use) is taken into consideration,and in which all patients are submitted to the same rehabilitation protocol after surgery.

There are some limitations in this study. First, even though this paper proves that open repair of rotator cuff tears is a safe an effective treatment method, it does not prove open repair is better than an arthroscopic repair, to do that, large multicenter randomized clinical trials need to be performed,as well as cost-effectiveness studies. Second, like the fact that massive rotator cuff tears were not evaluated, and the follow-up period is only of one year. The surveys used could be considered a limitation as well, given the fact that they are subjective in nature, and HRQoL surveys are generic instead of joint-specific, which could bias the results.

Author contributions

JGA was responsible for the study design, analysis, and writing of the paper. OMP was responsible for study implementation. JLV, JMGG,and ACV were responsible for study implementation and data collection. RTG conducted statistical analysis. All authors approved thefinal version of the paper for publication.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Financial support

This study was funded by Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, No.FIS/IMSS/PROT/EXORT/11/002. The funding source had no role in study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, writing or deciding to submit this paper for publication.

Research ethics

All procedures involving human participants in studies were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This paper was registered in the Ethics Committee platform at our hospital with the number R-2011-3401-43 CLIS 3401, and authorization number AA45-CCM-SCA. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Data sharing statement

Individual participant data (including data dictionaries) that underlie the results reported in this article, after deidentification (text, tables,fi gures, and appendices) are available. Study Protocol, Analytic Code and Clinical Study Report are shared. The data become available at www.figshare.com immediately following publication with no end date for researchers who wishes to access the data.

Plagiarism check

Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review

Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Shar eAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially,as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under identical terms.

REFERENCES

1. Clayton RA, Court-Brown CM. The epidemiology of musculoskeletal tendinous and ligamentous injuries. Injury. 2008;39:1338-1344.

2. Piitulainen K, Ylinen J, Kautiainen H, Häkkinen A. The relationship between functional disability and health-related quality of life in patients with a rotator cuff tear. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:2071-2075.

3. Neer CS. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:41-50.

4. Khan M, Simunovic N, Provencher M. Cochrane in CORR®: surgery for rotator cuff disease (review). Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:3263-2069.

5. Holmes RE, Barfield WR, Woolf SK. Clinical evaluation of nonarthritic shoulder pain: Diagnosis and treatment. Phys Sportsmed. 2015;43:262-268.

6. Whittle S, Buchbinder R. In the clinic. Rotator cuff disease. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:ITC1-15.

7. Cofield RH. Subscapular muscle transposition for repair of chronic rotator cuff tears. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1982;154:667-672.

8. Karas V, Hussey K, Romeo AR, Verma N, Cole BJ, Mather RC. Comparison of subjective and objective outcomes after rotator cuff repair.Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2013;29:1755-1761.

9. Burkhart SS, Lo IK. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:333-346.

10. Chahal J, Mall N, MacDonald PB, et al. The role of subacromial decompression in patients undergoing arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Arthroscopy. 2012;28:720-727.

11. Kolk A, Wolterbeek N, Auw Yang KG, Zijl JA, Wessel RN. Predictors of disease-specific quality of life after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair.Int Orthop. 2016;40:323-329.

12. Schmidt S, Vilagut G, Garin O, et al. Reference guidelines for the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey version 2 based on the Catalan general population. Med Clin (Barc). 2012;139:613-625.

13. Richards RR, An KN, Bigliani LU, et al. A standardized method for the assessment of shoulder function. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3:347-352.

14. Michener LA, McClure PW, Sennett BJ. American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Standardized Shoulder Assessment Form, patient selfreport section: reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2002;11:587-594.

15. Zhaeentan S, Von Heijne A, Stark A, Hagert E, Salomonsson B. Similar results comparing early and late surgery in open repair of traumatic rotator cuff tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:3899-3906.

16. Goutallier D, Postel JM, Radier C, Bernageau J, Zilber S. Long-term functional and structural outcome in patients with intact repairs 1 year after open transosseous rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2009;18:521-528.

17. Clavert P, Le Coniat Y, Kempf JF, Walch G. Intratendinous rupture of the supraspinatus: anatomical and functional results of 24 operative cases. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2016;26:133-138.

18. Papadopoulos P, Karataglis D, Boutsiadis A, Fotiadou A, Christoforidis J, Christodoulou A. Functional outcome and structural integrity following mini-open repair of large and massive rotator cuff tears: A 3-5 year follow-up study. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2011;20:131-137.

19. Hanusch BC, Goodchild L, Finn P, Rangan A. Large and massive tears of the rotator cuff: functional outcome and integrity of the repair after a mini-open procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:201-205.

20. Saraswat MK, Styles-Tripp F, Beaupre LA, et al. Functional outcomes and health-related quality of life after surgical repair of full-thickness rotator cuff tears using a mini-open technique: A concise 10-year follow-up of a previous report. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:2794-2799.

21. Vastamäki H, Vastamäki M. Postoperative stiff shoulder after open rotator cuff repair: a 3- to 20-year follow-up study. Scand J Surg 2014;103:263-270.

22. Mejía-Salazar CR, Sierra-Pérez M, Ruiz-Suárez M. Functional evaluation of the supraspinatus tendon repair comparing mini-open and open techniques. Acta Ortop Mex. 2016;30:191-195.

23. Connelly TM, Shaw A, O’Grady P. Outcome of open massive rotator cuff repairs with double-row suture knotless anchors: case series. Int Orthop. 2015;39:1109-1114.

24. Baysal D, Balyk R, Otto D, Luciak-Corea C, Beaupre L. Functional outcome and health-related quality of life after surgical repair of fullthickness rotator cuff tear using a mini-open technique. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1346-1355.

Clinical Trials in Orthopedic Disorder2018年1期

Clinical Trials in Orthopedic Disorder2018年1期

- Clinical Trials in Orthopedic Disorder的其它文章

- Information for Authors - Clinical Trials in Orthopedic Disorders (CTOD)

- A newfixation and reconstruction method versus arthroscopic reconstruction for treating avulsion fracture at the tibial insertion of the knee posterior cruciate ligament: study protocol for a nonrandomized controlled trial and preliminary results

- Total hip arthroplasty via the direct anterior approach versus lateral approach: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial

- Effects of balance training prior total knee replacement surgery: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial

- Evaluation of a computer-assisted orthopedic training system for learning knee replacement surgery:a prospective randomized trial