Akkermansia muciniphila的分离培养及其在不同人群的定植比较研究进展

王 磊,姚 泓,彭永正,李嘉雯,吴希阳,*

(1.暨南大学理工学院食品科学与工程系,广东 广州 510632;2.南方医科大学珠江医院检验医学部,广东 广州 510515)

胃肠道作为肠道微生物的主要活动场所,其壁上覆盖着的黏膜既能吸收营养物质,又能抵御有毒物质和病原菌的危害,是机体重要的免疫屏障[1-3]。黏膜也称黏液层,分为内黏液层和外黏液层,主要由杯状细胞合成和分泌,组成成分多为黏蛋白,并且部位不同,黏蛋白的种类也有所变化[4-6]。内黏液层和上皮细胞紧密结合,难溶于水,几乎无菌群存在;外黏液层在胃肠道的活动中被不断降解和剥落,众多肠道菌群生活在此调节机体内稳态[7-9]。疣微菌门和变形菌门较好地定植在黏液层中[10],且瘤胃菌科和双歧杆菌也有一定的黏蛋白降解能力,在其降解的过程中互利共生[11]。黏液层和在其中生存的菌群相互作用对机体健康影响深远,黏蛋白的降解和生成的稳态或紊乱常常能反映肠道内环境状况,因此,分离、鉴定黏液层中的菌群、细究菌群特异性成为研究重点[12-14]。

2004年,Derrien等[15]利用猪肠黏蛋白作为选择培养基首次从人体粪便中分离出了Akkermansia muciniphila,用16S rRNA基因测序分析出其属于疣微菌门,后被归类Akkermansiaceae科。A. muciniphila在人类肠道普遍定植,肠道黏液层至少存在8 种不同的Akkermansia属[16-17],且不同属的A. muciniphila很可能同时定植在同一人的肠道中[18]。快速检测不同人群体内Akkermansia属种类和含量,对不同Akkermansia属的高效率分离和鉴定具有重大意义。

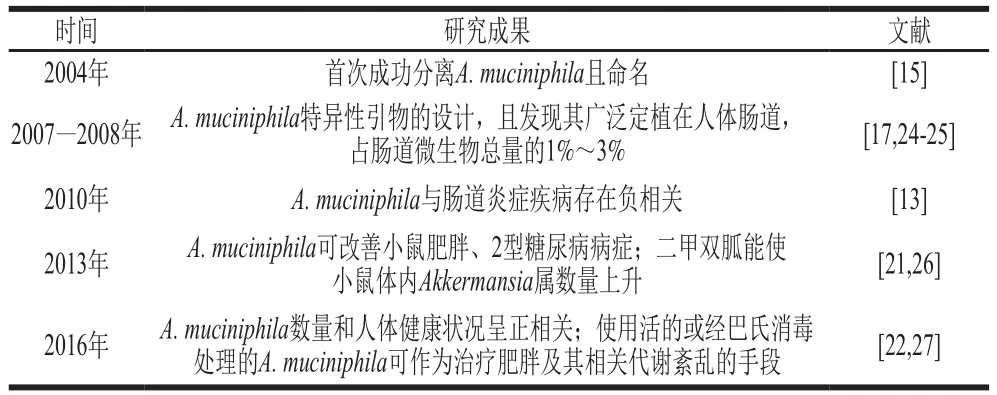

从人体粪便中首次分离出A. muciniphila已有10余年,但多数研究只是局限于A. muciniphila的生理特性,对于分子作用机制的探索还未出现。同时,分离方法的优化一直停滞不前,如何快速分离和分型一直是研究瓶颈。后工业化时代的饮食、生活方式和环境中物理和化学物质的变化,使肥胖和糖尿病发病率的逐年增加,也与肠道菌群息息相关[19-20]。目前也有研究成果显示A. muciniphila的数量与小鼠和人的肥胖、2型糖尿病等的发病率呈负相关[17,21-22],表1列举了A. muciniphila的主要研究进展,说明只有细究其培养条件,才能建立快速、准确的分离、纯化和鉴定技术,从不同宿主体内分离特异的Akkermansia属菌株,从而能够对其基因差异和生理生化功能进行比对。挑选出特异性菌株可以为后续的功能性研究和探索提供思路,用于机体胃肠道健康的研究。2016年,冯泽猛等[23]的综述里对A. muciniphila的定植环境、生理特性、对机体营养代谢的影响、与代谢性疾病及机体免疫相互作用等方面进行了总结。本文将侧重A. muciniphila的基因组信息及其分子生物学鉴定、分型技术、菌株分离与纯化过程,探讨现有的A. muciniphila的培养条件、分离和纯化方法的优缺点,了解人类与动物体内Akkermansia属的异同点,对比不同宿主之间定植的差异。

表1 A. muciniphila的研究进展Table 1 Milestones in A. muciniphila research

1 A. muciniphila的鉴定、分型和基因组信息

Akkermansiaceae为疣微菌门第Ⅱ科(Family II.Akkermansiaceae fam. nov.),Akkermansia属是科内唯一菌属,该属和其16S rRNA 极度相关的序列广泛存在于脊椎动物(如人、兔、小鼠和蟒蛇等)的肠道内[14]。Akkermansia属目前主要有A. muciniphila(2004年)和A. glycaniphila(2016年)2 个菌种被鉴定和分类,且A. muciniphila是疣微菌门中第一个被成功分离和鉴定的肠道菌[28],本文主要对人源A. muciniphila进行总结。

1.1 A. muciniphila的鉴定

菌种的鉴定技术主要为菌落形态分析、菌株生理生化实验以及分子技术等,A.muciniphila的鉴定主要是将三者进行联用,从而综合判断[15]。菌落形态主要从大小、色泽、形状以及是否存在荚膜等方面进行考察。A. muciniphila呈椭圆形,为非运动型的革兰氏阴性菌,单细胞长轴为0.6~1.0 μm,一般是单个或者成双菌落生长,极少是成群生长。在黏蛋白琼脂基础培养基上菌落呈现白色菌膜,菌落之间通过丝状结构相连接,单菌落大小约为0.7 mm[15]。挑选疑似目标菌,经过革兰氏染色后的镜检以及扫描电子显微镜观察,可以进行初步判断。

A. muciniphila在分别以葡萄糖、半乳糖、果糖、纤维二糖、N-乙酰葡萄糖胺、N-乙酰半乳糖胺和黏蛋白作为碳源的培养液中生长情况分别为微弱生长、不生长、不生长、不生长、微弱生长、微弱生长、最佳生长[15],且其主要细胞脂肪酸为4 类:C15:0(饱和直链)、反式C15:0(支链)、C15:03OH和C17:0,前3 类含量与A. glycaniphila相似[29]。A. muciniphila生理生化特性研究的不完全性(如氧损伤的影响)对鉴定过程造成了很大干扰。本课题组的前期成果发现,A. muciniphila在固体培养基上生长不稳定,这使其形态鉴定存在缺陷。基于纯培养技术的鉴定费时费力,需在分子和基因水平上进行分析来作为鉴定技术的补充。

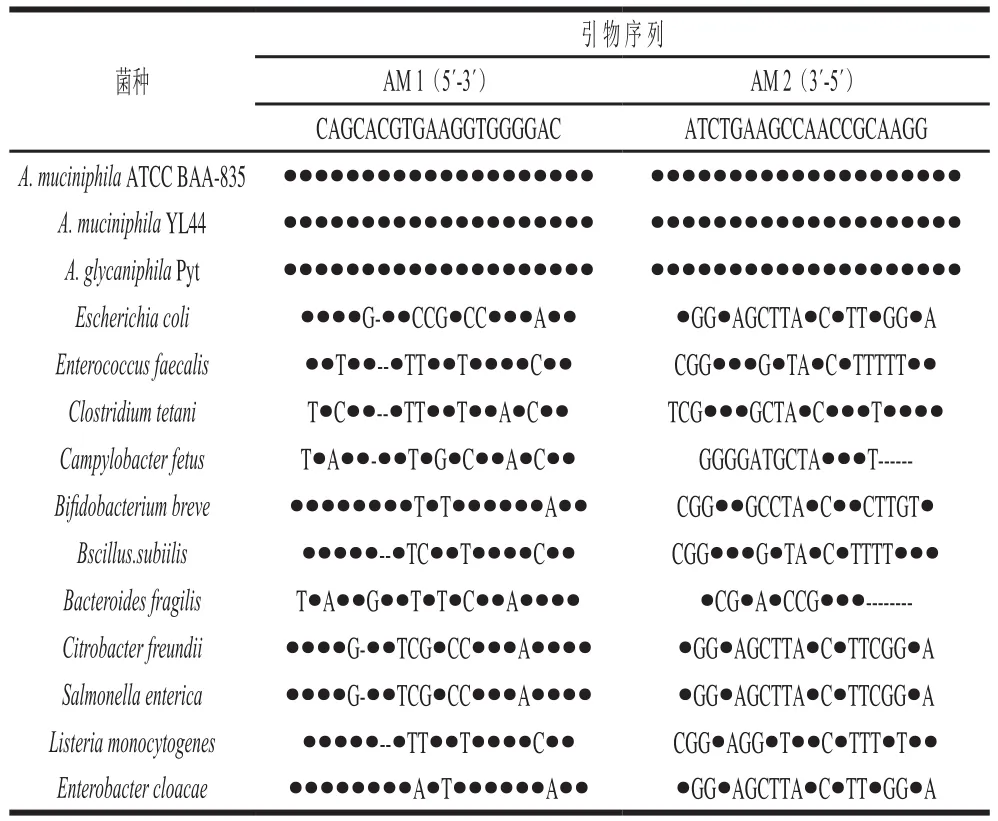

2004年,Derrien等[15]从A. muciniphila单菌落中提取DNA后用通用引物进行聚合酶链反应(polymerase chain reaction,PCR)扩增,纯化产物再进行16S rRNA基因序列测序,得到纯化产物长度为1 433 bp。经过序列比对得到与其99%相近的序列是未培养的肠道菌群,与疣微菌门中的Verrucomicrobium spinosum存在远缘关系(92%),之后归类于疣微菌门第Ⅱ科Akkermansiaceae[14-15],被鉴定为一种新的肠道菌群。2007年,Derrien等[24]设计出A. muciniphila的PCR特异性引物,产物片段为327 bp;Collado等[17]进一步验证了其特异性后用于A. muciniphila的定量PCR(quantitative PCR,qPCR)。2016年,Guo等[30]利用此特异性引物的PCR和qPCR定量能够较快确认人类肠道A. muciniphila的存在,并对其鉴定过程提供帮助。本实验室基于NCBI核酸数据库(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)中的Akkermansia属基因序列,通过分析可知,该特异性引物可以用于A.muciniphila和A. glycaniphila基因的扩增,见表2。因此这对引物无法直接特异性识别A. muciniphila,对其鉴定和定量都存在干扰。未来需要进一步优化反应条件或重新设计特异性引物,才能提高A. muciniphila的鉴定准确性。3 种技术的结合对于A. muciniphila的鉴定比较全面,但过程稍显繁琐,应随技术和设备的改进,开发快速、精准的鉴定技术。

表2 A. muciniphila特异性引物与Akkermansia属和其他细菌的16S rRNA基因的序列比对Table 2 Sequence alignment between A. muciniphila-specific primers and 16S rRNA genes of other Akkermansia bacteria and bacteria from other genera

1.2 A. muciniphila的分型

细菌的分型主要分为2大类:第一类是表型分型,根据血清型、噬菌体型、染色表现和生理生化实验等进行判断;第二类是分子分型,如脉冲场凝胶电泳技术、多位点序列分型、肠道细菌基因间保守重复序列(enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus,ERIC)和PCR联用技术分型等。

ERIC-PCR技术是基于肠道细菌基因组中非编码保守重复序列设计出特异性外向引物,扩增出不同细菌专属的指纹图谱用于进一步分型[31-32],目前关于A. muciniphila的分型主要依靠ERIC-PCR技术。2016年,Guo等[30]将分离出的22 株A. muciniphila使用ERIC-PCR技术分型,经过分析确认为12 种亚型,其中在3 人体内存在2 种不同的亚型,结果显示该技术存在较好的分型敏感度,这也是目前唯一关于A. muciniphila分型的报道。

1.3 A. muciniphila的基因组信息

A. muciniphila(ATCC BAA-835)的全基因组是由一条2 664 102 bp大小的环状染色体构成,总体GC含量为47.6%,存在2 176 种蛋白编码基因,整体编码能力为88.8%,1 408 种基因具有潜在功能性,768 种基因编码假定蛋白质,其中38 种蛋白质编码基因归类于假基因,共能编码61 种潜在的黏蛋白降解酶,但是缺少基因编码典型的黏膜结合域[15,18,33]。规律成簇的间隔短回文重复(clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats,CRISPR)基因位点负责在古细菌和细菌抵抗外源成分侵袭时表达可遗传的和适应性的天然免疫,ATCC BAA-835菌株基因组存在2 个CRISPR基因位点,正向重复序列大小分别为36、33 bp,重复次数分别为11 次和3 次,两者与9 个预测噬菌体序列相关,表明A. muciniphila在进化过程中频繁受细菌噬菌体的侵染[18,34-35],可能在黏液层中参与机体肠道屏障工作。

2015年,Caputo等[36]使用基于焦磷酸测序的罗氏454 Titanium系统结合鸟枪法以及5 kb双端测序技术对A. muciniphila Urmite进行基因组测序得出:A. muciniphila Urmite基因组草图大小为2 664 704 bp,仅存在56 个间隔,所有片段GC含量为54%~57%;超过80%的序列和ATCC BAA-835对应,其中2 192 个基因和ATCC BAA-835比对成功,52 个基因未在基因库中找到对应序列;通过抗生素抗性基因研究发现,存在8 种β-内酰胺酶类抗性基因,其中一种与万古霉素、氯霉素、甲氧苄啶、磺胺类和四环素抗性基因存在一定的联系。A. muciniphila基因组信息的缺乏使对其基因层次的探索研究难以进行,只有找出基因差异性和特异性才能更深入了解这类肠道优势菌在人体健康中扮演的角色。

2 A. muciniphila的分离、纯化和培养

各类组学技术能检测到不同菌群的多样性和功能性,但收集的信息只限于大分子(DNA、RNA和蛋白质)在微生态的作用,而需要探明某种菌株在体外环境中所表现的生理功能,就需分离纯菌株进行研究[37]。基因测序平台的飞速发展往往能检测到未分离或未培养的肠道菌,而相应的分离和培养技术却具有一定的滞后性。大多数成功分离出来的肠道菌一般是好氧菌或兼性厌氧菌,使用营养丰富的培养基或半组合培养基添加合适的碳源就能达到分离和培养的目的[28],而严格厌氧肠道菌分离和培养的难度大。1950年,Hungate[38]针对严格厌氧微生物设计出的培养技术给肠道微生物研究提供了巨大帮助,许多方法沿袭至今。A. muciniphila作为典型的肠道厌氧菌,其分离和纯化难度极大,学界逾20 年的研究,成功分离到的菌株十分有限,但培养扩增的方式不断有文献报道。

2.1 A. muciniphila的分离和纯化

2004年,Derrien等[15]总结Miller[39]和Hoskins[40]等的研究成果,将黏蛋白粉末进行纯化后制取高纯黏蛋白,作为A. muciniphila分离最关键的特异性碳源和氮源。配制基础液体培养基对新鲜、健康的高加索人粪便稀释液进行严格厌氧培养后,接种到黏蛋白固体基础培养基进行培养,使用软琼脂技术挑出目标菌进行数次纯化(整个过程保证严格厌氧环境),最后成功分离且证明为一种新的疣微菌门肠道革兰氏阴性菌,能够特异性降解黏蛋白作为能量大量增殖。

2016年,Guo等[30]将获取的172 份中国南方人群的粪便提取DNA用qPCR进行验证,选择含有A. muciniphila的阳性样品(Ct≤30),结合Derrien等[15]的分离方法进行前个两阶段的黏蛋白基础培养基选择性扩增。挑选黏蛋白固体基础培养基上的单菌落接种到添加了硫化钠和万古霉素的还原性巧克力培养基连续进行纯化后,最终成功分离得到22 株A. muciniphila,分为12 个亚型,首次从中国人群中分离A. muciniphila,为针对中国人群肠道菌群研究提供新的依据和思路。2012年,Hansen等[41]用万古霉素处理非肥胖性糖尿病小鼠,发现小鼠A. muciniphila的含量和丰度都有增长,且万古霉素常用来抑制革兰氏阳性菌的生长,有利于A. muciniphila的分离筛选。

2016年,Ouwerkerk等[29]从动物园中收集新鲜的网纹蟒蛇粪便,将0.2 g的网纹蟒蛇粪便稀释到含有0.5 g/L半胱氨酸盐酸盐的磷酸盐缓冲液中,利用流式细胞仪控制菌液浓度进行梯度稀释,再分别接种到黏蛋白固体基础培养基上。培养一段时间之后挑取单菌落再次接种到相同培养基上,重复操作,严格控制厌氧条件,直至得到纯化的A. glycaniphila菌株,这是首次从动物体内分离和纯化得到Akkermiansia属。2015年,Caputo等[36]用Lagier等[42]的培养组学方法对服用万古霉素或亚胺培南病人的粪便进行培养,宏基因组测序结果显示培养后的溶液中疣微菌门含量较多。但是Caputo等[36]参考Derrien等[15]的方法,在厌氧环境尝试分离其中的A. muciniphila,却以失败告终。说明A. muciniphila的起始存在的环境、选择性培养条件、操作方法等都可能对其分离和纯化产生很大影响。设计出巧妙的培养环境、优化分离和纯化方法最为关键,可以大大减少工作难度,提高分离效率。

2.2 A. muciniphila的培养

A. muciniphila在温度20~40 ℃和pH 5.5~8.0之间都能够生长,其中最佳温度是37 ℃、最佳pH值为6.5,需要严格厌氧生长(182 kPa、80% N2、20% CO2)。在以寡糖(葡萄糖、N-乙酰葡萄糖胺和N-乙酰半乳糖胺)为碳源的培养基中生长较为缓慢,在黏蛋白基础培养基中生长状况最好[15],黏蛋白基础培养基也是目前唯一的选择性培养基。2011年,van Passel等[18]将ATCC BAA-835接种到500 mL无氧黏蛋白(来自美国Sigma公司)液体基础培养基中,37 ℃过夜培养就可进行基因组DNA提取用于基因分析。2013年,Kang等[43]用黏蛋白液体培养基,在厌氧环境下(90% N2、10% CO2)培养出了可以达到后续实验要求的菌浓度。2015年,Reunanen等[44]用相同培养基(85% N2、10% CO2、5% H2)达到了同样的效果。将黏蛋白直接或纯化后配制成培养基都能成功培养A. muciniphila,但2 种培养基培养效果的比较还鲜有报道。2010年,Png等[45]从收集到的病人的膀胱液中提取和纯化黏蛋白,将其作为唯一碳源培养A. muciniphila。猪源黏蛋白是大多数报道中A. muciniphila培养基的关键成分,人源黏蛋白是第2种用于其培养的黏蛋白。未来尝试用其他种类黏蛋白培养A. muciniphila,比较培养效果,将会给探索黏蛋白和A. muciniphila的“特殊关系”提供证据。

脑心浸液肉汤(brain heart infusion broth,BHI)营养丰富,常用于菌种扩增,包括A. muciniphila的培养[15,46]。Shin[26]、Li Jin[47]、Ouwerkerk[29]以及Greer[48]等各自通过在BHI培养基中添加一定量的黏蛋白对A. muciniphila进行培养,发现能够满足其生长的营养要求,这种培养方式逐渐被推广。哥伦比亚肉汤培养基对A. muciniphila的培养也具有效果,Ganesh等[49]进行了验证。2016年,Plovier等[27]对黏蛋白基础培养基进行改造,用质量浓度16 g/L大豆蛋白胨、4 g/L苏氨酸以及25 mmol/L混合糖(葡萄糖、N-乙酰葡萄糖胺)来代替黏蛋白,结果发现能够达到相近的培养效果。

由以上可知,A. muciniphila在不含黏蛋白的培养基中也能生长,可能是环境选择让其使用其他碳源维持生存,而菌体是否出现变化有待探索。同时黏蛋白和其他碳源培养A. muciniphila的效果区别目前鲜有报道阐明,黏蛋白对其生长的特异性也亟待证明。A. muciniphila培养方式的不断探索对分离方法具有很大的指导意义,也能更好地进行体外实验和动物实验。

3 A. muciniphila在不同人群的定植比较

肠道菌群的多样性因个体差异(年龄、饮食和健康状况等)产生巨大的差距,且往往通过一种菌属的种类、数量和丰度等能够体现[50-52]。在不同年龄阶段,A. muciniphila的定植情况也具有一定的差异:年轻人粪便中A. muciniphila数量比老年人低,可能是老年人更注重身体健康,饮食较为平衡[22,30,53];中国百岁老人的A. muciniphila丰度明显弱于未满百岁人群[54],且欧洲成年人丰度较老年人更高[17];婴儿的丰度和定植率均低于成年人[17,30],但在一年内会达到成年人水平[17]。对年龄与A. muciniphila的相关性分析还需进一步研究,扩大样本量和优化检测技术是首要问题。

因地域不同,人群居住的环境和饮食结构存在差异,可能对一些菌群的定植存在影响:巴西人群A. muciniphila的定植率约79.17%[55],欧洲人群约为74.70%,而中国南方人群约为51.74%[30];A. muciniphila在澳大利亚的自闭症儿童粪便中的丰度较正常儿童低[16],而意大利[56]和美国[57]的自闭症儿童该菌群丰度比正常儿童要高。

肠道炎症疾病患者体内A. muciniphila的丰度较常人低[13,58-59],超重或肥胖人群以及Ⅱ型糖尿病患者体内A. muciniphila的数量、丰度都较常人低[60-61]。通过控制饮食、服用益生元和减肥手术等方式能够使A. muciniphila的数量、丰度升高[22,62],并且常锻炼的运动员肠道菌群的多样性更高,A. muciniphila数量明显高于肥胖和代谢异常的人群[63],说明合理饮食、作息规律以及适当锻炼可以使A. muciniphila数量和丰度保持在一个较高的水平,也间接证明A. muciniphila可作为衡量身体健康状况的潜在指标。

人类黏膜较为发达,Akkermansia属作为定植在宿主黏液层的肠道菌群,具有得天独厚的优势[33,37,64]。在正常饮食状态下,A. muciniphila可能会优先吸收食物中的营养而不是降解黏蛋白,其增殖较为平稳。受试人群主要食用膳食纤维为主的食物来限制卡路里的摄入(比正常生活状态下的饮食营养要低)并持续6 周后,宏基因组测序结果显示,相对于起始状态A. muciniphila的丰度较低[22],这说明A .muciniphila在不同物种体内定植表达和功能调控具有一定的差异,且不同个体肠道中定植的Akkermansia属可能不是A. muciniphila,发挥出的作用也有所不同。

4 结 语

Akkermansia属基因组信息的缺乏使其在肠道微生态和宿主机体健康的研究中长久被低估。A. muciniphila约占肠道微生物总量的1%~3%,是人体肠道中的优势菌群之一[17,25],而Akkermansia属的定量常用A. muciniphila的特异性引物进行分析。虽然A. muciniphila的特异性引物也能扩增A. glycaniphila基因序列,但可能无法识别Akkermansia属所有菌种,且A. muciniphila可能只占该属的一小部分,在一定程度上Akkermansia属在不同宿主上的定性或定量存在低估或偏差。目前关于A. muciniphila的研究成果中,其数量的增长或降低多数都是通过此对引物进行定量,而无法排除A. glycaniphila或其他Akkermansia属的干扰,对结果产生了一定误导。应合理、巧妙地利用现有资源,对现有分型的Akkermansia属进行基因水平上的分析,找到差异性和特异性,从而可以挑出具有特异性的Akkermansia属进行针对性的研究。A. muciniphila在人体内定植丰度与肥胖和Ⅱ型糖尿病常成负相关[65-66],而经过膳食或益生元补充等调控后,在改善机体健康的同时,A. muciniphila丰度也相应恢复甚至升高[21,25,67],可选择其在这类病症中作为肠道微生物的生物标记[68],因此A. muciniphila与健康息息相关。在精准医疗盛行的未来[69-71],通过结合这类技术,可以对与Akkermansia属相关的病症进行分析,针对目标菌种精准调控[72],甚至通过移植或服用目标菌株来改善机体健康。

A. muciniphila作为定植在黏液层中可特异性降解黏蛋白的肠道菌,与肠道健康紧密联系,但是鲜有证据直接证明其改善机体代谢。杯状细胞主要负责分泌大部分黏液层,黏液层在上皮细胞保留了高浓度的抑菌分子,且潘氏细胞分泌的防御素也充满在小肠黏液层的滤泡腺中,A. muciniphila在外黏液层中活动,在慢性病前期会放出信号,其数量和丰度也会降低,在中后期更加明显[22,33,60,68,73],这可能是因为在病症较为严重时高浓度抑菌物质和毒性物质充斥在周边,其生存环境较为恶劣。而在健康机体肠道黏液层中,A. muciniphila在分解黏蛋白时促进杯状细胞合成更多黏蛋白,二者相互促进[28,64],可能作为“友好因子”刺激杯状细胞始终保持活跃状态,调节机体肠道健康和加强肠道屏障。关于急性肠道疾病和A. muciniphila之间的联系还少出现报道,这可能是因为A. muciniphila在肠道中的潜在作用是抵抗机体慢性病,通过释放活性因子引起一系列机体反馈从而调控宿主健康。总之,Akkermansia属作为在宿主肠道中广泛定植的菌属,且目前还没有表现出任何致病性[33],应加快完善A. muciniphila的研究,早日将其列入安全益生菌的范畴,清晰分子作用机制,为人类健康助力。

[1] HONDA K, LITTMAN D R. The microbiota in adaptive immune homeostasis and disease[J]. Nature, 2016, 535: 75-84. DOI:10.1038/nature18848.

[2] MACKIE A R, ROUND A N, RIGBY N M, et al. The role of the mucus barrier in digestion[J]. Food Digestion, Research and Current Opinion, 2012, 3(1/2/3): 8-15. DOI:10.1007/s13228-012-0021-1.

[3] WILLIAMS C F, WALTON G E, JIANG L, et al. Comparative analysis of intestinal tract models[J]. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology, 2015, 6(1): 329-350. DOI:10.1146/annurevfood-022814-015429.

[4] BYRD J C, BRESALIER R S. Mucins and mucin binding proteins in colorectal cancer[J]. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews, 2004, 23(1/2):77-99. DOI:10.1023/A:1025815113599.

[5] MONIAUX N, ESCANDE F, PORCHET N, et al. Structural organization and classification of the human mucin genes[J]. Frontiers in Bioscience, 2001, 6: 1192-1206. DOI:10.2741/Moniaux.

[6] DEPLANCKE B, GASKINS H R. Microbial modulation of innate defense: goblet cells and the intestinal mucus layer[J]. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2001, 73(6): 1131S-1141S.

[7] MACKIE A R, ROUND A N, RIGBY N M, et al. The role of the mucus barrier in digestion[J]. Food Digestion, 2012, 3(1/2/3): 8-15.DOI:10.1007/s13228-012-0021-1.

[8] MEYER-HOFFERT U, HORNEF M W, HENRIQUES-NORMARK B,et al. Secreted enteric antimicrobial activity localises to the mucus surface layer[J]. Gut, 2008, 57(6): 764-771. DOI:10.1136/gut.2007.141481.

[9] JOHANSSON M E V, GUSTAFSSON J K, SJÖBERG K E, et al.Bacteria penetrate the inner mucus layer before inflammation in the dextran sulfate colitis model[J]. PLoS ONE, 2010, 5(8): e12238.DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0012238.

[10] KRAUS M, ÇETIN M, ARICIOĞLU F. The microbiota and gut-brain axis[J]. Journal of Mood Disorders, 2016, 6(3): 172-179. DOI:10.5455/jmood.20161004082122.

[11] BÄCKHED F, DING H, WANG T, et al. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2004,101(44): 15718-15723. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0407076101.

[12] JOHANSSON M E V, AMBORT D, PELASEYED T, et al.Composition and functional role of the mucus layers in the intestine[J].Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 2011, 68(22): 3635-3641.DOI:10.1007/s00018-011-0822-3.

[13] SOMMER F, BÄCKHED F. The gut microbiota-masters of host development and physiology[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2013,11(4): 227-238. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro2974.

[14] HEDLUND B P, DERRIEN M. Family II. Akkermansiaceae fam.nov[J]. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, 2010, 4: 809.DOI:10.1007/978-0-387-68572-4.

[15] DERRIEN M, VAUGHAN E E, PLUGGE C M, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a human intestinal mucin-degrading bacterium[J]. International Journal of Systematic & Evolutionary Microbiology, 2004, 54(5): 1469-1476. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.02873-0.

[16] WANG L, CHRISTOPHERSEN C T, SORICH M J, et al. Low relative abundances of the mucolytic bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila and Bifidobacterium spp. in feces of children with autism[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 77(18): 6718-6721. DOI:10.1128/AEM.05212-11.

[17] COLLADO M C, DERRIEN M, ISOLAURI E, et al. Intestinal integrity and Akkermansia muciniphila, a mucin-degrading member of the intestinal microbiota present in infants, adults, and the elderly[J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 73(23): 7767-7770.DOI:10.1128/AEM.01477-07.

[18] VAN PASSEL M W J, KANT R, ZOETENDAL E G, et al. The genome of Akkermansia muciniphila, a dedicated intestinal mucin degrader, and its use in exploring intestinal metagenomes[J]. PLoS ONE, 2011, 6(3): e16876. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0016876.

[19] SCHWARZ-ROMOND T. Microbiota: ‘bugging’ insights into metabolic regulation[J]. Molecular Metabolism, 2016, 5(9): Ⅳ-Ⅴ.DOI:10.1016/j.molmet.2016.07.006.

[20] WOTING A, BLAUT M. The intestinal microbiota in metabolic disease[J]. Nutrients, 2016, 8(4): 202-221. DOI:10.3390/nu8040202.

[21] EVERARD A, BELZER C, GEURTS L, et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls dietinduced obesity[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,2013, 110(22): 9066-9071. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1219451110.

[22] DAO M C, EVERARD A, ARON-WISNEWSKY J, et al.Akkermansia muciniphila and improved metabolic health during a dietary intervention in obesity: relationship with gut microbiome richness and ecology[J]. Gut, 2016, 65(3): 426-436. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308778.

[23] 冯泽猛, 包显颖, 印遇龙. 胃肠道黏液层中Akkermansia muciniphila的定殖及其与宿主的相互作用[J]. 中国农业科学, 2016, 49(8):1577-1584. DOI:10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2016.08.015.

[24] DERRIEN M. Mucin utilisation and host interactions of the novel intestinal microbe Akkermansia muciniphila[D]. Wageningen:Wageningen University, 2007: 53-130.

[25] DERRIEN M, COLLADO M C, BEN-AMOR K, et al. The mucin degrader Akkermansia muciniphila is an abundant resident of the human intestinal tract[J]. Applied & Environmental Microbiology,2008, 74(5): 1646-1648. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01226-07.

[26] SHIN N R, LEE J C, LEE H Y, et al. An increase in the Akkermansia spp. population induced by metformin treatment improves glucose homeostasis in diet-induced obese mice[J]. Gut, 2013, 63: 706-707.DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305370.

[27] PLOVIER H, EVERARD A, DRUART C, et al. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice[J]. Nature Medicine,2016, 23: 107-113. DOI:10.1038/nm.4236.

[28] DERRIEN M, BELZER C, VOS W M D. Akkermansia muciniphila,and its role in regulating host functions[J]. Microbial Pathogenesis,2016, 106: 171-181. DOI:10.1016/j.micpath.2016.02.005.

[29] OUWERKERK J P, AALVINK S, BELZER C, et al. Akkermansia glycaniphila sp. nov., an anaerobic mucin-degrading bacterium isolated from reticulated python faeces[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2016, 66(11): 4614-4620.DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.001399.

[30] GUO X, ZHANG J, WU F, et al. Different subtype strains of Akkermansia muciniphila abundantly colonize in southern China[J].Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2016, 120(2): 452-459. DOI:10.1111/jam.13022.

[31] WIKSTRÖM P, ANDERSSON A C, FORSMAN M. Biomonitoring complex microbial communities using random amplified polymorphic DNA and principal component analysis[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology,1999, 28(2): 131-139. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6941.1999.tb00568.x.

[32] VERSALOVIC J, KOEUTH T, LUPSKI J R. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 1991, 19(24): 6823-6831. DOI:10.1093/nar/19.24.6823.

[33] DERRIEN M, VAN PASSEL M W J, VAN DE BOVENKAMP J H B, et al. Mucin-bacterial interactions in the human oral cavity and digestive tract[J]. Gut Microbes, 2010, 1(4): 254-268. DOI:10.4161/gmic.1.4.12778.

[34] BARRANGOU R, FREMAUX C, DEVEAU H, et al. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes[J]. Science,2007, 315: 1709-1712. DOI:10.1126/science.1138140.

[35] VAN DER OOST J, JORE M M, WESTRA E R, et al. CRISPR-based adaptive and heritable immunity in prokaryotes[J]. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 2009, 34(8): 401-407. DOI:10.1016/j.tibs.2009.05.002.

[36] CAPUTO A, DUBOURG G, CROCE O, et al. Whole-genome assembly of Akkermansia muciniphila sequenced directly from human stool[J]. Biology Direct, 2015, 10(1): 1-11. DOI:10.1186/s13062-015-0041-1.

[37] BELZER C, DE VOS W M. Microbes inside-from diversity to function: the case of Akkermansia[J]. The ISME Journal, 2012, 6(8):1449-1458. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2012.6.

[38] HUNGATE R E. The anaerobic mesophilic cellulolytic bacteria[J].Bacteriological Reviews, 1950, 14(1): 1-49.

[39] MILLER R S, HOSKINS L C, MILLER R. Mucin degradation in human colon ecosystems. fecal population densities of mucin-degrading bacteria estimated by a ‘most probable number’ method[J].Gastroenterology, 1981, 81(4): 759-765.

[40] HOSKINS L C, AGUSTINES M, MCKEE W B, et al. Mucin degradation in human colon ecosystems. isolation and properties of fecal strains that degrade ABH blood group antigens and oligosaccharides from mucin glycoproteins[J]. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 1985, 75(3): 944-953. DOI:10.1172/JCI111795.

[41] HANSEN C H F, KRYCH L, NIELSEN D S, et al. Early life treatment with vancomycin propagates Akkermansia muciniphila, and reduces diabetes incidence in the NOD mouse[J]. Diabetologia, 2012, 55(8):2285-2294. DOI:10.1007/s00125-012-2564-7.

[42] LAGIER J C, ARMOUGOM F, MILLION M, et al. Microbial culturomics: paradigm shift in the human gut microbiome study[J].Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 2012, 18(12): 1185-1193.DOI:10.1111/1469-0691.12023.

[43] KANG C S, BAN M, CHOI E J, et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from gut microbiota, especially Akkermansia muciniphila, protect the progression of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis[J]. PLoS ONE,2013, 8(10): e76520. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0076520.

[44] REUNANEN J, KAINULAINEN V, HUUSKONEN L, et al.Akkermansia muciniphila adheres to enterocytes and strengthens the integrity of the epithelial cell layer[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2015, 81(11): 3655-3662. DOI:10.1128/AEM.04050-14.

[45] PNG C W, LINDÉN S K, GILSHENAN K S, et al. Mucolytic bacteria with increased prevalence in IBD mucosa augment in vitro utilization of mucin by other bacteria[J]. American Journal of Gastroenterology,2010, 105(11): 2420-2428. DOI:10.1038/ajg.2010.281.

[46] SHEN J, TONG X, SUD N, et al. Low-density lipoprotein receptor signaling mediates the triglyceride-lowering action of Akkermansia muciniphila in genetic-induced hyperlipidemia[J]. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis & Vascular Biology, 2016, 36(7): 1448-1456.DOI:10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307597.

[47] LI Jin, LIN Shaoqiang, VANHOUTTE P M, et al. Akkermansia Muciniphila protects against atherosclerosis by preventing metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in Apoe−/−mice[J]. Circulation, 2016, 133(24): 2434-2446. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019645.

[48] GREER R L, DONG X, MORAES A C F, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila mediates negative effects of IFNγ on glucose metabolism[J]. Nature Communications, 2016, 7: 13329-13339.DOI:10.1038/ncomms13329.

[49] GANESH B P, KLOPFLEISCH R, LOH G, et al. Commensal Akkermansia muciniphila exacerbates gut inflammation in Salmonella typhimurium-infected gnotobiotic mice[J]. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(9):e74963. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0074963.

[50] CLAESSON M J, CUSACK S, O’SULLIVAN O, et al. Composition,variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2011,108(Suppl 1): 4586-4591. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1000097107.

[51] TIIHONEN K, OUWEHAND A C, RAUTONEN N. Human intestinal microbiota and healthy ageing[J]. Ageing Research Reviews, 2009,9(2): 107-116. DOI:10.1016/j.arr.2009.10.004.

[52] GERRITSEN J, SMIDT H, RIJKERS G T, et al. Intestinal microbiota in human health and disease: the impact of probiotics[J]. Genes &Nutrition, 2011, 6(3): 209-240. DOI:10.1007/s12263-011-0229-7.

[53] BIAGI E, NYLUND L, CANDELA M, et al. Through ageing, and beyond:gut microbiota and inflammatory status in seniors and centenarians[J]. PLoS ONE, 2010, 5(5): e10667. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0010667.

[54] WANG F, YU T, HUANG G, et al. Gut microbiota community and its assembly associated with age and diet in Chinese centenarians[J].Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2015, 25: 1195-1204.DOI:10.4014/jmb.1410.10014.

[55] TYAKHT A V, KOSTRYUKOVA E S, POPENKO A S, et al. Human gut microbiota community structures in urban and rural populations in Russia[J]. Gut Microbes, 2013, 4(3): 2469-2476. DOI:10.1038/ncomms3469.

[56] DE ANGELIS M, PICCOLO M, VANNINI L, et al. Fecal microbiota and metabolome of children with autism and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified[J]. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(10): e76993.DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0076993.

[57] KANG D W, PARK J G, ILHAN Z E, et al. Reduced incidence of prevotella and other fermenters in intestinal microflora of Autistic children[J]. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(7): e68322. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0068322.

[58] VIGSNÆS L K, BRYNSKOV J, STEENHOLDT C, et al. Gramnegative bacteria account for main differences between faecal microbiota from patients with ulcerative colitis and healthy controls[J]. Beneficial Microbes, 2012, 3(4): 287-297. DOI:10.3920/BM2012.0018.

[59] PAPA E, DOCKTOR M, SMILLIE C, et al. Non-invasive mapping of the gastrointestinal microbiota identifies children with inflammatory bowel disease[J]. PLoS ONE, 2012, 7(6): e39242. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0039242.

[60] QIN J, LI Y, CAI Z, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes[J]. Nature, 2012, 490: 55-60.DOI:10.1038/nature11450.

[61] ZHANG H, DIBAISE J K, ZUCCOLO A, et al. Human gut microbiota in obesity and after gastric bypass[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2009, 106(7): 2365-2370. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0812600106.

[62] CLARKE S F, MURPHY E F, O’SULLIVAN O, et al. Exercise and associated dietary extremes impact on gut microbial diversity[J]. Gut,2014, 63: 1838-1839. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306541.

[63] DERRIEN M, VAN BAARLEN P, HOOIVELD G, et al. Modulation of mucosal immune response, tolerance, and proliferation in mice colonized by the mucin-degrader Akkermansia muciniphila[J].Frontiers in Microbiology, 2011, 2: 166. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2011.00166.

[64] PREIDIS G A, AJAMI N J, WONG M C, et al. Composition and function of the undernourished neonatal mouse intestinal microbiome[J]. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 2015, 26(10):1050-1057. DOI:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.04.010.

[65] KARLSSON C L J, ÖNNERFÄLT J, XU J, et al. The microbiota of the gut in preschool children with normal and excessive body weight[J].Obesity, 2012, 20(11): 2257-2261. DOI:10.1038/oby.2012.110.

[66] LIU F, LING Z, XIAO Y, et al. Dysbiosis of urinary microbiota is positively correlated with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Oncotarget,2017, 8(3): 3798-3810. DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.14028.

[67] CANDELA M, BIAGI E, SOVERINI M, et al. Modulation of gut microbiota dysbioses in type 2 diabetic patients by macrobiotic Ma-Pi 2 diet[J]. The British Journal of Nutrition, 2016, 116(1): 80-93.DOI:10.1017/S0007114516001045.

[68] YASSOUR M, MI Y L, YUN H S, et al. Sub-clinical detection of gut microbial biomarkers of obesity and type 2 diabetes[J]. Genome Medicine, 2016, 8(1): 1-14. DOI:10.1186/s13073-016-0271-6.

[69] COLLINS F S, VARMUS H. A new initiative on precision medicine[J]. New England Journal of Medicine, 2015, 372(9): 793-795. DOI:10.1056/NEJMp1500523.

[70] JAMESON J L, LONGO D L. Precision medicine-personalized,problematic, and promising[J]. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey,2015, 70(10): 612-614. DOI:10.1056/NEJMsb1503104.

[71] ASHLEY E A. The precision medicine initiative: a new national effort[J]. JAMA, 2015, 313(21): 2119-2120. DOI:10.1001/jama.2015.3595.

[72] WU M, MCNULTY N P, RODIONOV D A, et al. Genetic determinants of in vivo fitness and diet responsiveness in multiple human gut bacteroides[J]. Science, 2015, 350: aac5992. DOI:10.1126/science.aac5992.

[73] MCGUCKIN M A, ERI R, SIMMS L A, et al. Intestinal barrier dysfunction in inflammatory bowel diseases[J]. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 2008, 15(1): 100-113. DOI:10.1002/ibd.20539.