立陶宛建筑之木

鲁塔·莱塔奈特/Rūta Leitanaitė

尚晋 译/Translated by SHANG Jin

无论怎样引人注目的技术创新手段运用到蓝图和工地上,有些传统建筑材料都不会退出历史的舞台,木材就是其中之一。人们甚至会注意到,木材与新发明结合在一起时,会在当代建筑上获得越来越丰富的多样性。因此,木材倍受建筑师青睐是由于它适合大胆、因地制宜的建筑创作,而住户喜欢它是因其本身的温暖、舒适和自然。

在立陶宛建筑的历史长河中,木材有着令人信服的地位,对于一个反复提出的问题尤其如此,“如果说我们拥有的一切几乎都是从西欧抄袭和改造来的巴洛克、苏联巨构建筑和典型项目以及千篇一律的玻璃摩天楼,那什么才是立陶宛的本土建筑?”在追溯立陶宛建筑特色起源的道路上,若是忽视了民族木建筑、木庄园以及数百年来改变了立陶宛景观和城市风貌的公共建筑和住宅,那就是不可饶恕的。

立陶宛各时期和各类型木建筑的特色是什么?文化、环境、社会因素和技术的发展给木建筑的演变带来了怎样的影响?木材在立陶宛当代建筑中作为建筑材料和审美手段的情况如何?

本文简要地介绍了立陶宛木建筑不同寻常的多样性,并考察了木建筑最具代表性、最独特的实例。

在研究者克里斯蒂娜·施陶佩特看来,立陶宛一直是以森林著称的。在历史上的各个时期,立陶宛的林地面积占比为20%~55%,适宜的气候条件形成了大量阔叶林和针叶林。选择木材作为建筑材料是因为缺少石材及其他合适的建筑材料。与欧洲其他地方的趋势不同,立陶宛在13世纪成为独立国家之初,木建筑就是主流。木材被用于防御工事、住宅和宗教建筑。后来随着城镇的扩张和国家经济状况的改善出现了大量砖建筑。

20世纪之前的大部分木建筑,都是由非专业人士设计和建造的。由于木作传统流传广泛,并且这种艺术和工艺代代相传,所以不乏能造出高品质建筑的专家:几乎每个男人都会木工。立陶宛各地最古老的木建筑(民族特色农场、村庄和历史最久的教堂)在表达上各有千秋。不过,随着时间的流逝,新的建筑技术出现,各种时尚开始席卷全国。

1萨莫吉希亚农场,卡特那村/A samogitian homestead,Kartena village (图片来源/Source: 立陶宛露天博物馆/Open-air Museum of Lithuania)

2奥克施泰提亚的村落/A Village in Aukštaitija(摄影/Photo:OAML)

3苏瓦凯加一个有取水井的谷仓/Suvalkija, a thrashing barn and a well with a sweep(图片来源/Source: Vinksupiai Vil, Sakiai Reg.)

时间与不利的历史变迁(战争、火灾、工业化)摧毁了立陶宛大部分木建筑遗产。20世纪下半叶,历史记忆的延续暂时被截断,木建筑的传统近乎消失,木建筑也不再流行。

如今在立陶宛,木建筑遗产作为立陶宛文化和特色的重要组成部分,正在国家和地方各层面的计划以及欧盟的资助下进行复兴。尽管如此,修复木建筑遗产并进行保护是非常昂贵的。除此之外,能完成历史木建筑高标准修复的技术人才也十分短缺。

民族建筑(基于拉莎·贝尔塔希乌特博士 文)

在立陶宛,乡村文化直到二战以前都是主流。80%的人住在农村,延续着木作数百年的传统。全国各地有着形形色色的建筑,其差别不仅在于体积和比例,还有施工和建造的技术。

农场是农作的一个单位,它包括一小块土地和住宅,以及所有的农房、院子、花园、果园和小型建筑。在历史的长河中涌现出各种精心设计的农场建筑。

立陶宛西部的特色在于不经规划的村庄(有最古老的建筑)星罗棋布,阡陌交通,漫山遍野。萨莫吉希亚地区(图1)的农场十分宽敞,2~3个院子,几汪池水,郁郁葱葱。在农场中间,最重要的建筑包围着主院:住宅、粮仓、地窖。在院子中间曾有一棵百年橡树,后来改成一个装饰性的木十字架或木柱龛。这座住宅将典型的院子与农家院隔开。牲口棚略远,而打谷仓、谷棚和干草仓更远。

在这座住宅的中央曾有一个开放式灶台。1000年前,牲口在冬天会和主人一起住在屋里。萨莫吉希亚的新型住宅里保留了开放式灶台,随着时间的变迁成了住宅中间宽大的封闭烟囱。

奥克施泰提亚(东立陶宛,图2)的村庄大多有一条街道贯穿其中,各家都有一条狭长的土地。这源于16世纪西欧村庄的模式。由于地块狭长,建筑布局必须尽可能方便、经济。地块的形状规整,相互并列成排,街道两侧均有建筑:住宅和谷仓在一侧,外屋在另一侧。

19世纪末以前的奥克施泰提亚住宅保留了简单的结构,由3个大小相似的空间组成。家庭的日常生活在有采暖的主空间,住宅的另一端留给客人。这两部分都可以由无采暖的中央门廊到达。直到19世纪中叶,大多数住宅都没有烟囱,开放的炉中冒出的烟熏着住户。

20世纪之交,这些村庄被分解为一个个农场。在苏瓦凯加(西南地区,图3),建筑围着宽敞的长方形院子布置。这个院子又被栅栏分为典型区和工作区。这里有果园和花园,院子中间有一口井,牲口棚旁边还有一个水池。农场有若干排树。立陶宛人不喜欢严整的形式,所以在农场的布置上会努力追求个性。即使在按长方形平面新建的农场上也经常能看到不规则排布的建筑,或是随意布局的绿植。

立陶宛农场的主要特征是良好的空间组织。主院周围是大小相似的建筑。更大的建筑盖在较远的地方,以避免侵占院子的空间。小的外屋围着一个较小的院子。这种大小比例营造出许多怡人的空间。

住宅有5~10个房间。最重要的房间位于建筑的各端,而在中部靠近厨房和门廊的地方增加了更多房间。它们往往还有一个通向室外的独立出口。20世纪初,富农的住宅还有一个带加高阁楼、夹层和两层前厅的芒萨屋。农宅的平面几乎为正方形,并逐渐接近城市住宅。

村庄最主要的变化发生在二战后。农民被迫迁入集体农村宿舍,而古老的村庄和家庭经营的农场被破坏。极少数农场得以幸存,而那些都在森林或不适合农业的偏远地区。目前《遗产名录》中有43座村庄和受保护的个体农场及其建筑。

No matter what impressive technological innovations take on the blueprints and construction sites, some of the traditional construction materials do not concede their positions; wood being one of them. One could even notice that wood, combined with new inventions, gains more and more versatility in contemporary architecture. Therefore, wood is preferred by the architects because its suitability for bold architectural improvisations and, by the users – because of inherent warmth, cosiness, and naturalness.

In the context of history of Lithuanian architecture, wood has a cogent role. Especially, when it comes to a repeated question: "What is indigenous Lithuanian architecture, if almost everything we have is copied and altered baroque from Western Europe,soviet megastructures and typical projects and uniform glass skyscrapers? "While searching for the origins of the identity of Lithuanian architecture, it would be irremissible to ignore ethnographic wooden architecture, wooden manors, public and residential buildings which evolution gradually altered landscape and cityscape of Lithuania through the past centuries.

What feature are characteristic of Lithuanian wooden building of various periods and types?What influence did cultural, environmental, social factors and the evolution of technology have on the changes in wooden architecture? What is the status of wood, as construction material and aesthetic tool, in Lithuanian contemporary architecture?

This article presents in a concise manner the extraordinary variety of wooden architecture in Lithuania, examining the most characteristic and most distinctive examples of wooden architecture.

According to a researcher Kristina Štaupaitė,Lithuania has always been known for its forests. At different periods in its history, Lithuania's wooded land surface has ranged from 20% to 55%. Favourable climatic conditions allowed the formation of broadleaved and coniferous forests. The choice of wood as a building material was determined by the lack of stone and other suitable material for construction.Differently from the tendency in other parts of Europe, in Lithuania from the very beginnings as an independent state in the 13th century wooden architecture was dominant, wood being used for the construction of defensive, residential and sacral buildings. Brick buildings began to proliferate later,with the expansion of towns and an improvement in the state's financial circumstances.

The greater part of wooden architecture up to the 20th century was designed and built by non-professionals. Since the traditions of wooden construction were especially widespread and this art and craft was handed down from generation to generation, there was no shortage of specialists able to build buildings of a high quality: almost every man knew how to work with wood. The expressions of the oldest wooden architecture (on ethnographic farmsteads, in the villages, and the oldest churches)in the various regions of Lithuania were different.However, with the passage of time, newer building technologies, one might say - fashions, began to spread throughout all of the country.

Time and unfavourable historical changes (wars,fires, industrialisation) destroyed most of Lithuania's heritage of wooden architecture. In the second half of the 20th century, occupation, the development of historical memory was curtailed, the traditions of wooden architecture almost died out, and the popularity of wooden architecture declined.

Today in Lithuania, the heritage of wooden architecture, as a significant part of the culture and identity of Lithuania, is being revived by means of various programmes on a state and local level, as well as with the support of EU funds. All the same,restoring the heritage of wooden architecture and protecting it is expensive, and, besides that, there is a shortage of skilled people, able to restore the historical wooden buildings to a high standard.

Ethnographic architecture (based on the text by Dr. Rasa Bertašiūtė)

In Lithuania up to World War II rural culture dominated with about 80% of the population living in the countryside and maintaining the centuriesold tradition of wooden construction. Specific types of buildings emerged in various parts of the country,differing not only in their volume, proportions, but also in their construction and building technology.

A farmstead is a farming unit, comprised of a plot of land together with the residential house and all the farm buildings, yards, gardens, orchards and smallscale architecture. In the flow of history various types of planned farmstead structures developed.

Characteristic of West Lithuania were the villages(the oldest in their structure) that without any plan came to be dotted haphazardly throughout the region with an irregular network of streets and farmsteads freely spread out in the landscape. In Samogitia region(Fig. 1), the farmsteads were spacious, with 2-3 yards,several ponds, and with abundant greenery. In the centre of the farmstead around the main yard the most important buildings were located: the residential house, the barns, cellars. In the middle of the yard there would have been a hundred-year-old oak tree which was later replaced by a decorative wooden cross or a wooden column shrine. The residential house separated the representative yard from the farmyard. The animal sheds were set at a distance, and the threshing barns together with sheds and the hay barns were set further away.

In the centre of the house there used to be an open hearth. Ten centuries ago, during the winters,animals would live in the house together with their masters. In the newer type of house in Samogitia the open hearth survived, which over time became a spacious closed chimney in the centre of the house.

In Aukštaitija (East Lithuania, Fig. 2) villages with a single street running through it and a narrow strip of land belonging to each family predominated,copying the model of 16th century Western European villages. The plots were narrow and the buildings had to be laid out as conveniently and economically as possible. The plots of land were of a regular shape and were positioned in rows next to one another with the buildings on both sides of the street: the residential houses and barns on one side and the outbuildings on the other.

The residential house in Aukštaitija up to the end of the 19th century preserved the simple structure,consisting of three similar sized spaces. The everyday life of the family took in the main heated space, the other end of the house was set aside for guests. One could access both parts through the unheated central porch. Up to the middle of the 19th century most of the houses had no chimney, bathing the residents in a smoke, coming from an open furnace.

A r o u n d t h e t u r n o f t h e 2 0 t h c e n t u r y, t h e

v i l l a g e s w e r e b r o k e n u p i n t o i n d i v i d u a l f a r m s t e a d s.I n S u v a l k i j a (S o u t h W e s t r e g i o n, F i g. 3), t h e b u i l d i n g s w e r e p o s i t i o n e d a r o u n d a s p a c i o u s r e c t a n g u l a r y a r d,w h i c h w a s d i v i d e d i n t o t h e r e p r e s e n t a t i v e a n d w o r k z o n e s b y f e n c e s. A n o r c h a r d a n d f l o w e r g a r d e n w e r e p l a n t e d, a w e l l d u g i n t h e m i d d l e o f t h e y a r d, a n d t h e r e w a s a p o n d b y a n a n i m a l s h e d. A f a r m s t e a d w o u l d h a v e s e v e r a l r o w s o f t r e e s. L i t h u a n i a n s d i d n o t l i k e s t r i c t l y r e g u l a r f o r m s, s o i n l a y i n g o u t a f a r m s t e a d t h e r e w a s a s t r i v i n g f o r i n d i v i d u a l i t y. E v e n i n t h e n e w f a r m s t e a d s b u i l t t o a r e c t a n g u l a r p l a n, o n e c o u l d o f t e n s e e f a r m b u i l d i n g s l a i d o u t i n i r r e g u l a r l y o r g r e e n e r y p l a n t e d t o a l o o s e p a t t e r n.

庄园建筑(基于达莱·普如凯尼内博士文)

在近500年的历史中 (从15世纪-20世纪初),庄园都是立陶宛政治、经济和文化活动的枢纽,而庄园农业是经济的基础。受过良好教育、踌躇满志的自由贵族统治着国家,他们是公共和宗教建筑的委托项目和资金的主要负责人。通过庄园,技术创新、进步的建造技术和全球性建筑思想传到了国家最遥远的地方。这些创新与当地传统融合在一起,成为立陶宛特色的组成部分,并影响了城乡文化。

贵族占人口的6%~7%,目前立陶宛约有4000处庄园。由于木头作为建筑材料十分方便、廉价而且易得(从庄园所属的森林中), 木建筑就成了主流。庄园木建筑在17世纪中叶达到黄金时代,建造它们的是显赫的地主和国王。然而,立陶宛在17~20世纪失去了其最早、尤为丰富而有原创性的木遗产。

通常庄园位于优美的自然环境中。大的庄园最多曾有40座建筑。最大的庄园有果园,最有钱的贵族会在庄园所属的小镇或村庄建造教堂(带家族陵墓)。

主要建筑上的细节达到了无以复加的地步。领主府、仆人房、粮仓、藏宝室、厨房、地窖或冰窖,以及马厩——都代表着主人的财富。房前的开敞空间突出了住宅的显赫地位,从18世纪末起又装点了花池或花圃。

室内外装饰风格以巴洛克时期、19世纪的新古典主义和折中主义的全球性建筑风格为主。

19世纪末,最大的一批庄园被改造为进步农场;然而,1863年的起义及后续的社会变革导致小贵族走向贫穷。1926年的土地改革加快了变卖庄园,并迁入城市的步伐。1940年代,庄园及其文化环境遭到废弃。

如今庄园木建筑正经历着复兴。国家和私人业主将它们修复,并按当代需求进行改造。不过,木建筑依然没有得到像砖建筑一样的重视。

宗教建筑(基于克里斯蒂娜·施陶佩特 文)

立陶宛宗教建筑只能从它成为天主教国家的1387年后谈起。最早的木教堂形象非常朴素,并模仿砖建筑的特征。专业和民间建筑之间的区别一目了然。事实上,民族特色和当时的本土精神在民间建筑上表现得最为突出。教堂的建造者大多不为人知,而赞助人和建筑工程负责人却名垂青史。

今天立陶宛保留着265座木教堂。最古老的建于17世纪下半叶,而木教堂的黄金时代是18世纪。当时89%在建的教堂都是木建筑。

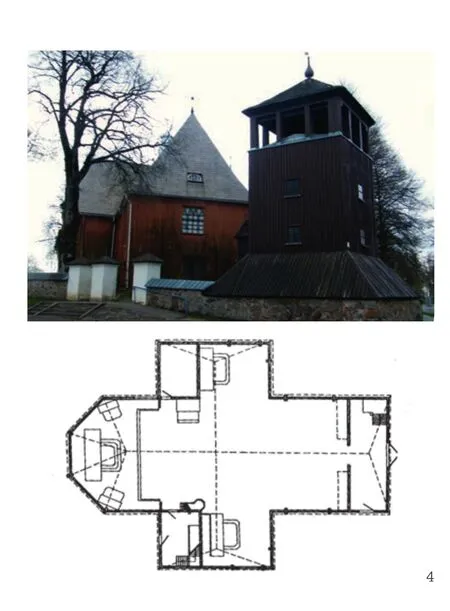

立陶宛有两个民族地区最能看到特别的建筑特征。在萨莫吉希亚(立陶宛西北部)可以看到一系列原汁原味的巴洛克风格木教堂。它们都属于殿堂型,单中殿,接近希腊十字形;有高高的双坡顶,与墙等高。雄伟的表达形式和硕大的比例是巴洛克教堂的典型特征,主立面上有许多小塔,还有侧廊和屋顶的中央横档(图4)。在奥克施泰提亚(立陶宛东北部),教堂是按拉丁十字平面建造的,有一个或3个中殿,屋顶要矮得多。它们的形象更加轻盈,主立面更窄,通常进行垂直划分,而在室内有前厅和唱诗区。

教堂的室外以实用和质朴为特征,而室内的巴洛克风格造型则让人惊叹不已。室内布置着绚烂多彩的绘画。中间华丽的巴洛克——洛可可风格祭坛上满是绚烂的镂雕,深受世人喜爱。

19世纪,立陶宛大部分领土都被沙俄占领,教堂的资金支持因意识形态而枯竭,木教堂的数量也随之减少。由于工厂制造的零件和加工材料的使用,民族差异也被消除了。

20世纪之交发生了剧变。社会意识改变,务农人员的生活得到改善,专业化建造的砖教堂开始取代木教堂。老教堂被拆除,新的砖建筑取而代之。20世纪木教堂的困境成了难题。二战后,立陶宛并入苏联,教堂在社会中的地位一落千丈。许多教堂因利用不当、保护不力,原真性遭到严重破坏。

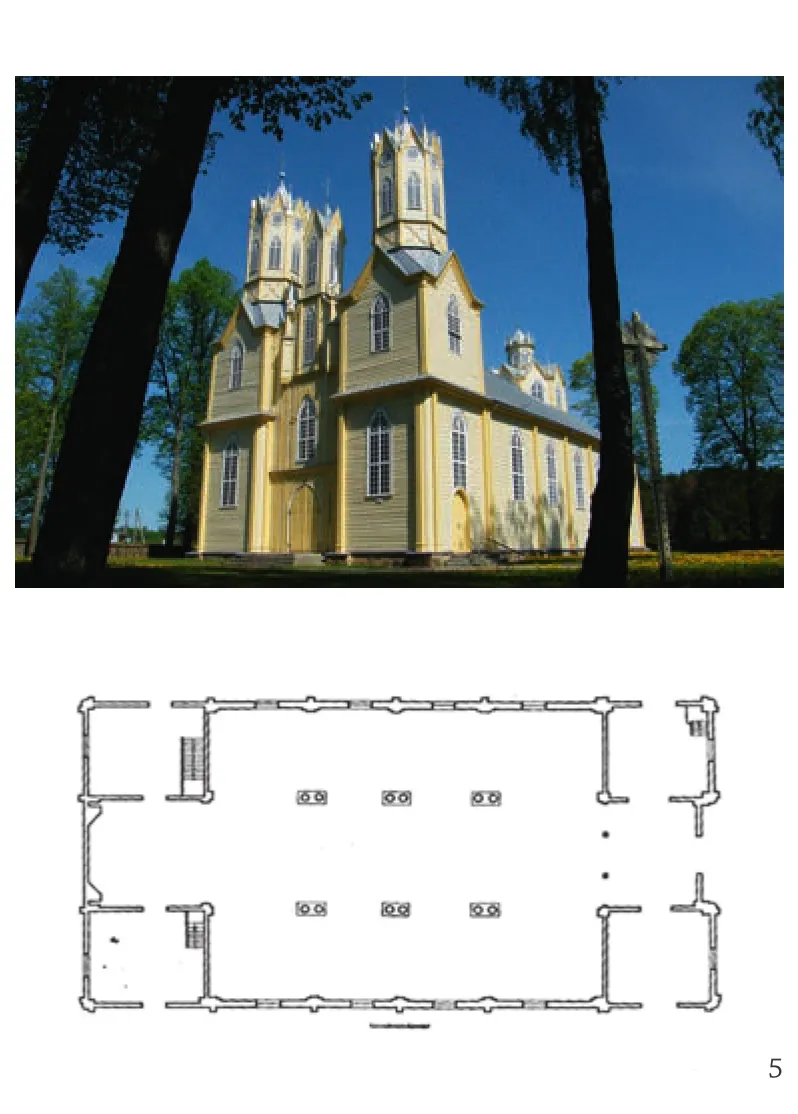

然而,还有一些独具特色的木宗教典型建筑得以保存。其中之一就是内马朱奈圣使徒彼得和保罗教堂(图5)。这座带有鲜明新哥特造型的木教堂是浪漫主义时代艺术思想的代表。专业的工匠根据建筑师托马什·蒂谢茨基的设计建造了这座教堂。室内是由当地雕刻家和艺术家布置的,所以本土风格元素显而易见。长方形的平面源于古典主义传统。圣坛上方巨大的穹顶、带双塔的主立面和室内则呼应着巴洛克传统。在立陶宛浪漫主义时期,新哥特式砖建筑大行其道,并衍生出多种形式。但就木建筑而言,这座教堂是现存的孤例。

4 普拉特利艾圣使徒彼得和保罗教堂/The Plateliai Church of the Holy Apostilles Peter and Paul

5内马朱奈圣使徒彼得和保罗教堂/The Nemajūnai Church of the Holy Apostilles Peter and Paul

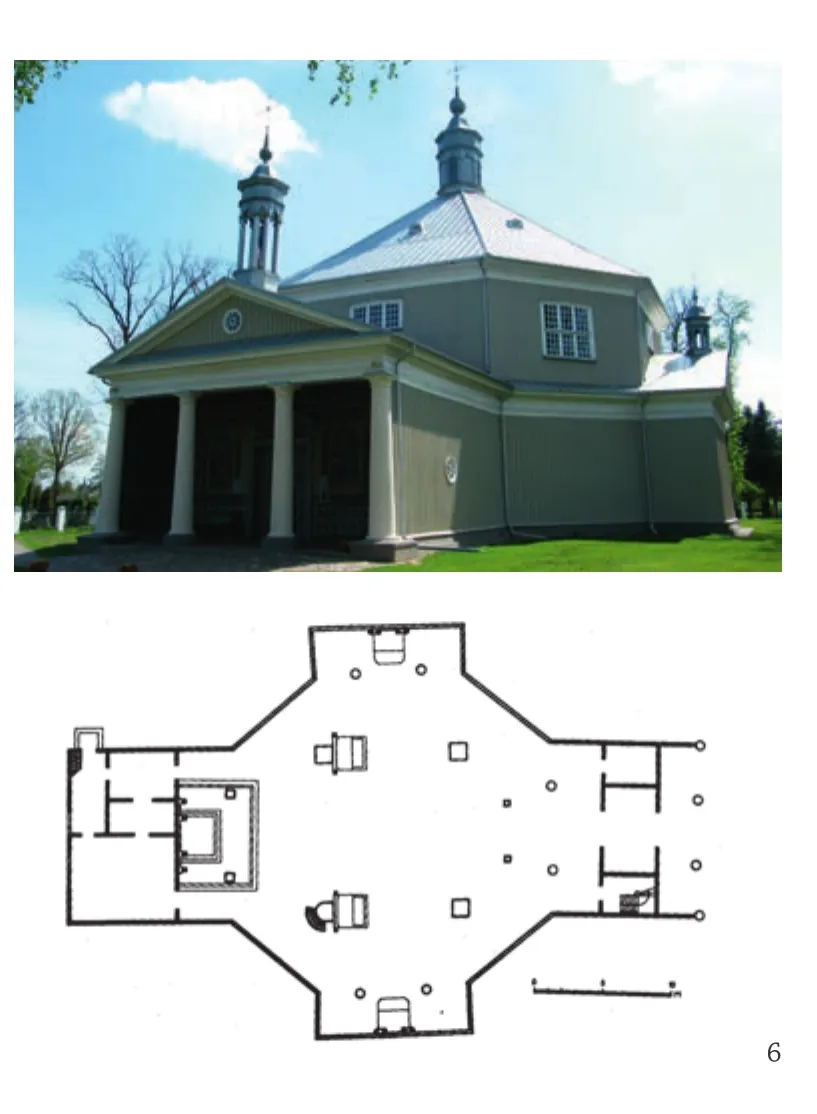

6格里什卡布迪斯显圣教堂/The Griškabūdis Churches of the Transfiguration(4-6摄影/Photos: Arvydas Kumpis, 线图/Plans: From the book A. Jankeviciene, Lithuanian wooden churhes, chapels and bell towers)

格里什卡布迪斯显圣教堂(图6)是立陶宛仅存的按古典主义传统建成的多边形木教堂。它是一个宽大的八边形,带长方形的门廊和环柱廊——圣器室,侧边还有许多小礼拜堂。八边形的观景楼立在金字塔形的屋顶和附属楼上。主立面上有四根多立克柱的门廊,墙上装饰着彩画——立陶宛仅存的实例。大量新古典主义建筑元素是通过幻象和彩画来表现的。室内因最令人难忘的一个历史主义时期祭坛组熠熠生辉——5座新古典主义和新巴洛克风格祭坛。另一侧是精美的巴洛克晚期和洛可可风格的风琴(1804),这是立陶宛该时期最珍贵的乐器。

The main feature of Lithuanian farmsteads was the good organisation of space. The main yard had buildings of a similar size positioned around it. Larger buildings were built a little further away in order not to encroach on the yard space. The small outbuildings were clustered around a smaller yard. This size ratio created spaces of a pleasant aspect.

The residential house consisted of 5-10 rooms.The most important rooms were located at the ends of the building, while in the central part, next to the kitchen and porch, more rooms were added, often with a separate exit to the outside. At the beginning of the 20th century the houses of wealthy peasants were added a mansard room with a heightened loft, a mezzanine, and a two-storey antechamber. The plan of a rural dwelling became almost square in shape and gradually began to resemble a city residence.

The most significant changes in the villages took place after World War II. With the peasants forced to move to the collective farm settlements, the old villages and family-run farms were destroyed. Very few farmsteads survived, and those were the ones in forests or in out of the way locations, inconvenient for agriculture. At present in the List of Heritage Properties there are 43 villages, as well as protected and individual farmsteads together with their buildings.

Manor architecture (based on the text by Dr. Dalė Puodžiukienė)

For almost five centuries (15th to the beginning of the 20th c.) the manor was the hub around which Lithuania's political, economic and cultural activities revolved, with manorial agriculture being the basis of the economy. Free, well-educated and ambitious noblemen ruled the State and were in the main responsible for the commissioning and funding of public and sacral buildings. It was through the manor estates that technical innovations, progressive building techniques and cosmopolitan architectural ideas reached the furthest outposts of the country.Those innovations, mingled with local traditions,became an integral part of Lithuania's identity and influenced rural and urban culture.

The nobility made up about 6%-7% of the population. There were about 4000 estates on the current territory of Lithuania and since wood as a building material was convenient, cheap and easily obtainable (from the woods that belonged to the manors), timber buildings dominated. Wooden manorial architecture reached its golden age in the middle of the 17th century, when they were built by important landlords and the king. However, the earliest, particularly rich and original wooden heritage of Lithuania was lost during 17th-20th centuries.

Usually the manors were located in a beautiful natural environment. Large estates used to have up to 40 buildings. The biggest estates had an orchard, and the richest noblemen used to build a church (with a family mausoleum) in the small town or village that belonged to the manor.

The main buildings were built with the utmost attention to detail. The residence of a lord, the house for servants, the granaries, treasure-house, kitchen,cellar or icehouse, and the stables – they all represented the wealth of the owners. The importance of the residential house was accentuated by a open space in the front of it, which, from the end of the 18th century,was adorned with flower-beds or a parterre.

The cosmopolitan architectural styles of the Baroque period, Neoclassicism and the eclectic styles of the 19th century were dominant in both exterior and interior décor.

At the end of 19th century, the largest manors were transformed into progressive farms; however,the 1863 uprising and the social transformations of that followed resulted in the impoverishment of smaller noblemen. The tendency of selling the manors and moving to the cities was accelerated by the land reform of 1926. The 1940s the Soviet government swept away the intelligentsia and the landlords;therefore the manors and their cultural environment were abandoned.

Today wooden manor buildings are experiencing a renaissance. The state and private owners are restoring and adapting them to contemporary needs.However, wooden buildings still do not get as much attention as brick ones.

Sacred architecture (based on the text by Kristina Štaupaitė)

One can only talk about Lithuanian sacral architecture from 1387 when Lithuania became a Catholic country. The first wooden churches were aesthetically simple, replicating the features of brick churches. The differences between professional and folk architecture could be plainly seen. As it happens, it is in folk architecture that ethnographical characteristics and the local spirit of the time are best revealed. The church builders themselves most often remained unknown, the patrons and persons in charge of the building work being mentioned in the records.

Today there are 265 wooden churches left in Lithuania. The eldest ones were built in the second half of the 17th c., but the golden age of wooden churches was the 18th century. At that time, 89% of all the churches being built were wooden.

There are two ethnographical regions in Lithuania where specific architectural features can be best discerned. In Samogitia (the north-western part of Lithuania) one can find an entire network of authentic wooden Baroque-style churches. All of them are of the hall type, with a single nave, almost of a Greek cross form with a high two-pitch or hip roof, level with the height of the walls. A monumental expression and massive proportions were typical of Baroque churches, featuring small towers above the main facade, the side naves and the roof's central crosspiece (Fig. 4). In Aukštaitija (the north-eastern part of Lithuania), the churches were built according to the Latin cross plan, with one or three naves and a considerably less high roof. They were lighter in appearance, the main facades narrower, quite often vertically divided, while inside one had an antenave and choir areas.

The exterior of the churches was characterised by function and modesty, while the interior amazed one with impressive Baroque-style forms. The interior was decorated with colourful painting. Imposing central altars of a Baroque-Rococo-style composition,abundantly enriched by flamboyant, openwork carvings, were popular.

In the 19th century, with the greater part of the territory of Lithuania under the occupation of the Tsarist Russian Empire financial support for churches waned for ideological reasons, and the number of wooden churches declined accordingly. Because of the use of factory-manufactured parts and processed materials, there was a levelling-out of ethnographical differences.

Huge transformations took place at the turn of the 20th century when with a change in the mentality of society and with improvements in the lives of people working in the agricultural sector,professionally-built brick churches began to displace wooden ones. The old churches were demolished and replaced by new ones in brick. The predicament of wooden churches in the 20th century was problematic. After World War II, when Lithuania was annexed by the USSR, the role of the Church in society was seriously diminished. A great deal of harm was done to the authenticity of the churches because of their inappropriate use and the failure to protect them properly.

However, there are several unique examples of wooden sacral architecture preserved. One of those is the Nemajūnai Church of the Holy Apostilles Peter and Paul (Fig. 5). The wooden church with expressive neo-Gothic forms became the embodiment of the artistic ideas of the epoch of Romanticism.Professional craftsmen built the church according to the project by the architect Tomasz Tyszecki, while the interior was fitted out by local sculptors and artists, therefore elements of indigenous décor are obvious. The rectangular plan was created according to traditions of Classicism, whereas the substantial cupola above the presbytery, the main two-tower facade and the interior echo the traditions of the Baroque. During the epoch of Romanticism in Lithuania examples of brick neo-Gothicism were very widespread and took on various forms but as regards wooden architecture this church is the sole such object still surviving.

19-20世纪城市中的住宅和公共建筑(基于英格丽达·韦柳特,阿斯塔·拉什凯维丘捷博士 文)

不少常见的类型或城市木建筑都是不同凡响的。比如城市住宅:通常以侧立面临街,一层高,按长向住宅设计建造,上为双坡锡屋顶。主人住在房子的一部分里,并将其他部分出租。

农场类住宅也建在小镇中,并延伸到郊区,吸收在乡村为主流的民间建筑传统。它们与街道距离更远,有花园,通常只住一户。这些单层的长方形住宅有时会加高,以便做出夹层和带芒萨顶的阁楼,以及带玻璃窗的凉廊。

在更大的城镇里,带4个或更多出租屋的公寓开始涌现。它们通常为2层,呈长方形,双坡顶,几乎没有装饰,有时带玻璃门廊和阳台。

在自然环抱之中的更大城镇,其郊区在不断拓展,特别是温泉小镇。它们引以为豪的别墅以丰富多样的建筑方案而闻名(图7)。这些别墅往往都造型不对称,有小塔楼、凉廊、门廊、断口芒萨顶、用于装饰的风格化涡卷,以及小塔楼亮丽的盔型盖顶。沙俄建筑对维尔纽斯别墅的建造产生了最大的影响,波兰扎科帕内风格的元素在一战后广为流传。这里还能发现摩尔风格和立陶宛民间建筑的元素。在德鲁斯基宁凯的温泉小镇还可以看到俄国、瑞士、波兰及其他欧洲温泉的影响。在考纳斯,国家风格是举足轻重的,而在克莱佩达地区可以看出德国建筑的传统。

更为复杂的形式通常出现在小庄园建筑上(图8)。另一方面,避暑别墅更为简单,适应度假者的各种需求,并抛弃了奇异的装饰。在温泉度假地,最重要的公共聚集场所就是用于休闲的疗养院(温泉小镇的主要建筑,图9)。

很多木建筑的布局都很简单,它的图纸是由所谓的“绘图员”完成的。不过,也有著名建筑师设计的项目。

7建筑师费利克萨斯·维兹巴拉斯1932年为作曲家尤奥扎斯·格鲁奥迪斯设计的别墅图/ The composer Juozas Gruodis villa by architect Feliksas Vizbaras, 1932(摄影/Photo: I.Veliute)

8瓦茨洛瓦斯·米赫涅维丘斯住宅/Vaclovas Michnevičius House(摄影/Photo: A.Raskeviciute)

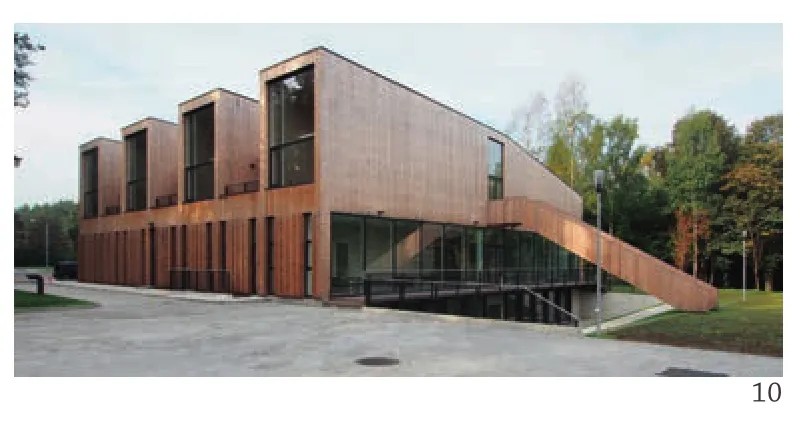

10奥德留斯·安布拉萨斯建筑事务所设计的鲁珀特艺术教育中心,2013年建造,建筑师奥德留斯·安布拉萨斯,维尔马·阿多莫尼特,明道加斯·雷克莱蒂斯/ Rupert Art and Education centre by Audrius Ambrasas architects, 2013,arch. Audrius Ambrasas, Vilma Adomonytė, Mindaugas Reklaitis(摄影/Photo: 奥德留斯·安布拉萨斯建筑事务所/Audrius Ambrasas Architects

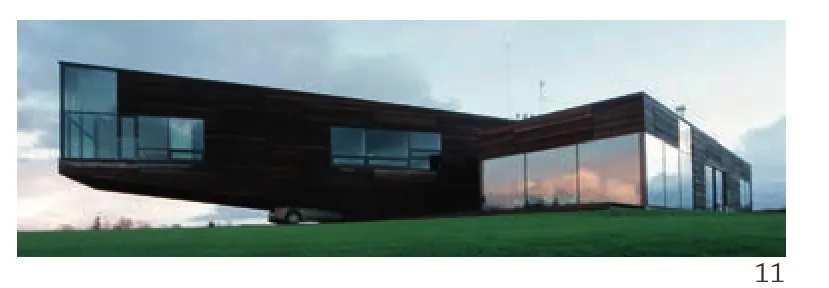

11金陶塔斯·纳特克维丘斯事务所设计的乌特里艾住宅,2006年建造,建筑师金陶塔斯·纳特克维丘斯,里马斯·阿多迈蒂斯,雷蒙达斯·巴布劳斯卡斯/House in Utriai by G. Natkevicius & Co, 2006, arch. Gintautas Natkevičius,Rimas Adomaitis, Raimundas Babrauskas(摄影/Photo:R.Urbakavičiaus)

12阿克 吐里建筑 事务所设 计的维尔 纽斯住 宅,2013年建 造,建筑师米 尔达·雷 克维米契 内,阿尔 达·蒂 尔维凯特 ,卢卡斯·雷克 维丘斯/House in Vilnius by Aketuri architektai, 2013,arch. Milda Rekevičienė, Alda Tilvikaitė, Lukas Rekevičius(摄影/Photo: Norbert Tukaj)

13奥德留斯·安布拉萨斯建筑事务所设计的别墅G,2014年建造,建筑师奥德留斯·安布拉萨斯,维尔马·阿多莫尼特,达留斯·尤斯克维丘斯/Villa G by Audrius Ambrasas architects, 2014,arch. Audrius Ambrasas, Vilma Adomonyte, Darius Juskevicius.

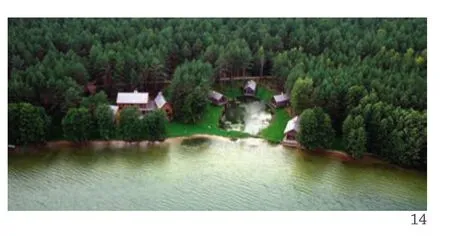

14Arches事务所设计的纳克奇季比斯度假屋,2010年建造,建筑师阿纳斯·利奥拉,罗兰达斯·利奥拉,埃德加·涅斯基斯,留陶拉斯·内克罗修斯,卢卡斯·拉任斯卡斯/Resort Nakcižibis by Arches, 2010, arch. Arūnas Liola,Rolandas Liola, Edgaras Neniškis, Liutauras Nekrošius, Lukas Lažinskas (摄影/Photo: R.Urbakavičiaus)

15Erdvės norma事务所设计的“海、沙、风”别墅,2009年建造,建筑师金特拉斯·普里科基斯,阿斯塔·普里科基耶涅,因加·蒂奎塞特,安德留斯·韦卢蒂斯;木窗花艺术家:马里乌斯·约努蒂斯/The Villa"Sea. Sand. Wind" by Erdvės norma, 2009,arch. Gintras Prikockis, Asta Prikockiene, Inga Tikuisyte, Andrius Velutis; wooden tracery artist: Marius Jonutis(摄影/Photo:Simonas Prikockis)

当代建筑

在立陶宛建筑中使用木材,从1990年代再度流行起来。木材,在历史上曾作为廉价、方便的材料用来快速建造房屋,而在当代建筑中又呈现出多样化的形象。

在立陶宛1990年恢复独立并归还私有财产之后,很多立陶宛人都梦想成真了——拥有一座带土地的独户住宅。对苏联时期破坏家园环境的行径感到厌倦的人们,在为自家的个性和舒适努力,而这通常离不开传统建筑的形式和自然材料。建筑中的木材(尤其是完成面)越来越受欢迎。

在当代专业化建筑上,木材不再被视为最廉价的材料,而被用来打造与众不同的形象和高品质的环境(图10)。因此,木材的外观和耐久度愈发重要。材料的质量及其加工方式,还有营造和建筑方案的精细施工越来越受重视。木材通常用于可见的位置,在完成面和装修上(其他材料主要用于施工,图11)。木材是一种千变万化的材料,并在最新的立陶宛建筑中创造出一种当代形象(图12),而使用木材的新技术(如胶合板)更有助于表达的多样化(图13)。

当代立陶宛建筑师作品的特点之一是关注并尊重文脉。大部分当代木建筑出现在木材纹理和色彩可与之融为一体的自然环境中并非巧合(图14)。使用传统材料的灵感不仅源于自然——木材被用在希望与传统建筑相结合的地方(图15)。由于天然的特性和“暖人”的形象,木材在娱乐设施上备受青睐。

□(本文中的信息和图片出自展览“立陶宛建筑之木”。该展览在立陶宛文化委员会的支持下,由立陶宛建筑师协会主办(策展:鲁塔·莱塔奈特)。展览作者:拉萨·贝尔塔希乌特博士(民族建筑:村庄、农场)、达莱·普如凯尼内博士(庄园)、克里斯蒂娜·施陶佩特(宗教建筑)、英格丽达·韦柳特和阿斯塔·拉什凯维丘捷博士(19世纪至20世纪初立陶宛城镇木建筑)、鲁塔·莱塔奈特(立陶宛当代木建筑)。对于本文中所用的图片,我们致谢:立陶宛露天博物馆、考纳斯市博物馆、总档案员办公室、维尔纽斯大学图书馆、手稿部、肖利艾·奥施洛斯博物馆、立陶宛庄园数据库、文化遗产中心、遗产保护图书馆。建筑师事务所和摄影师:A.Raškevičiūtė, I. Veliutė, A. Bartišiūtė-Janušienė, A. Kumpis, V.Gužienė, D. Puodžiukienė, R. Bertašiūtė, A. Jankevičienė, R.Urbakavičius, L. Garbačauskas, N. Tukaj, S. Prikockis等。)

The Griškabūdis Church of the Transfiguration(Fig. 6), is the only surviving polygonal wooden church built in the Classicist tradition in Lithuania.It is of a spacious octagonal shape with rectangular annexes of a porch-portico and a presbytery-sacristy,as well as small side chapels. Octagonal belvedere towers rise above the pyramid-shaped roof and annexes. The main facade is made up of a portico with four Doric columns, the walls of which are decorated with polychromatic painting, the only example of its kind in Lithuania. The proliferation of neo-Classicist architectural elements are created by the use of illusionist and polychromatic painting. The interior is graced with one of the most impressive altar ensembles of the epoch of Historicism - five neo-Classicist and neo-Baroque0style altars. On the other side there is an ornate late Baroque and Rococo-style organ (1804), one of the most valuable instruments of that time in Lithuania.

Residential, public buildings in the cities in 19th-20th centries (based on the text by dr. Ingrida Veliute and Asta Raškevičiūtė)

Several common types or urban wooden architecture can be distinguished. These would be:urban residential dwellings, usually with the side facade turned to the street, one storey tall, built to an elongated house design, covered with a tin dualpitched roof. The owner, who lived in one part of the house, would rent out the other parts.

Expanding out to the suburbs, taking on the traditions of folk architecture dominant in the countryside, farmstead-type houses were built in the towns. They were built further away from the street, with gardens, usually meant for one family.The one-storey high, rectangular-shaped houses were sometimes given extra height by having a mezzanine and an attic with a mansard roof, as well as a glazed veranda.

In the larger towns rented houses began to proliferate with 4 or more apartments for rent.They usually had two storeys, were rectangular in shape, covered with a dual-pitched roof, had minimal decoration, sometimes glazed porches, and balconies.

The developing suburbs of larger towns surrounded by nature and in particular the spa towns could boast of their villas, distinguished by the great variety of architectural solutions used (Fig. 7).The villas were usually asymmetrical in shape, with turrets, verandas, porches, mansard roofs with a broken contour, stylised volutes used for decoration,and the sleek helmet-type coverings of the turrets.Tsarist Russian architecture had the greatest influence on the construction of Vilnius villas, and elements of the Polish style (of Zakopane) became prevalent after World War I. One can also find elements of the Moorish-style and Lithuanian folk architecture. In the spa town of Druskininkai one can see the influence of Russian, Swiss, Polish and other European spas. In Kaunas the national style was important, while in the territory of Klaipėda one can discern the traditions of German architecture.

More complicated forms were frequently to be found in the architecture of smaller manor houses(Fig. 8). Summer houses, on the other hand, were simpler, adapted to the needs of holidaymakers and dispensed with the use of fancy decor. In the spa resorts the most important public gathering place was the Kurhaus (the principal building in a spa town, Fig.9) intended for entertainment.

Many of the wooden buildings had a simple layout, the drawings being prepared by so-called'draughtsmen'. However, there were also projects by very well-known architects.

Contemporary architecture

Wood in Lithuanian architecture became popular again in the last decade of the 20th century.Historically used as a cheap and convenient material for the speedy construction of buildings, wood in contemporary architecture has a versatile image.

After the restoration of Lithuania's independence and the restitution of private property in 1990, many Lithuanians were able to fulfil their dreams - to have a single-family house with a plot of land. Tired after the destruction of the environment in which they lived during the Soviet period, people strove for individuality and comfort in their houses, and this was often connected to the traditional forms and natural materials of traditional architecture. Wood in architecture (particularly as regards the finish) became increasingly more desirable.

In contemporary professional architecture wood is no longer perceived as the cheapest of materials but is being used to create a distinctive image and an environment of a high quality (Fig. 10). For this reason, the appearance and durability of wood are becoming important. A lot of attention is being paid not only to the quality of the material and the way it is worked but also to the construction, as well as the meticulous implementation of architectural solutions. Wood is most often used where it can be seen - in the finish and fittings (other materials being predominantly used in construction) (Fig. 11). It is a very versatile material and in the newest examples of Lithuanian architecture wood is used to create a contemporary image (Fig. 12), while the the new technologies in the use of wood (e.g. plywood) serve to contribute to the variety of expression (Fig. 13).

One of the features of the work of contemporary Lithuanian architects is the attention and respect paid to context. It is no coincidence that most of contemporary wooden architecture may be found in the natural environment where the texture and colour of wood are an intrinsic part (Fig. 14). The use of a traditional material is inspired not just by nature - wood is used where one wants to create a connection with traditional architecture (Fig. 15).Because of its natural quality and its "warm" image,wood is especially favoured in recreational facilities.□ (The information and pictures, used for this article, is a part of an exhibition "Wood in Lithuanian architecture". The exhibition was organised by Architects Association of Lithuania (curator: Rūta Leitanaitė), supported by the Council for Culture of Lithuania. The authors of the exhibition: dr. Rasa Bertašiūtė (ethnographic architecture: villages,farmsteads), dr. Dalė Puodžiukienė (manorial estates), Kristina Štaupaitė (sacral architecture), dr.Ingrida Veliūtė and Asta Raškevičiūtė (the wooden architecture of Lithuanian towns from the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century), Rūta Leitanaitė (contemporary wooden architecture in Lithuania). For the pictures used in the article we are grateful to: Open air museum of Lithunia, Kaunas City museum, Office of the Chief Archivist, Vilnius University library, Manuscripts department, Šiauliai Aušros museum, Database of Lithuanian Manors,Centre of Cultural Heritage, Library of Heritage protection, architects'offices and photographers: A.Raškevičiūtė, I. Veliutė, A. Bartišiūtė-Janušienė, A.Kumpis, V. Gužienė, D. Puodžiukienė, R. Bertašiūtė,A. Jankevičienė, R. Urbakavičius, L.Garbačauskas, N. Tukaj, S. Prikockis and others.)