越过山丘,我看到天空在向我招手

孙昌建

电影快结束的时候,有王力宏驾机欲撞向日本军舰的镜头,此时他的视线中出现了一片天空,一名战友正拉着一顶降落伞缓缓下降,这名战友实际上已经被日本飞行员锁定了射击目标……当我看到这一组镜头的时候,看懂了这部名叫《无问西东》的电影。我不仅能讲出王力宏饰演的沈光耀的原型是谁,也能讲出那名跳伞战友的原型,以及那一片云南的天空和杭州的天空到底有些什么不同。

这是因为我写了一本名叫《鹰从笕桥起飞》的非虚构作品,内容虽然只是中国空军抗战的鳞爪碎片,但背后却是一片又一片或硝烟弥漫或无比蔚蓝的天空。

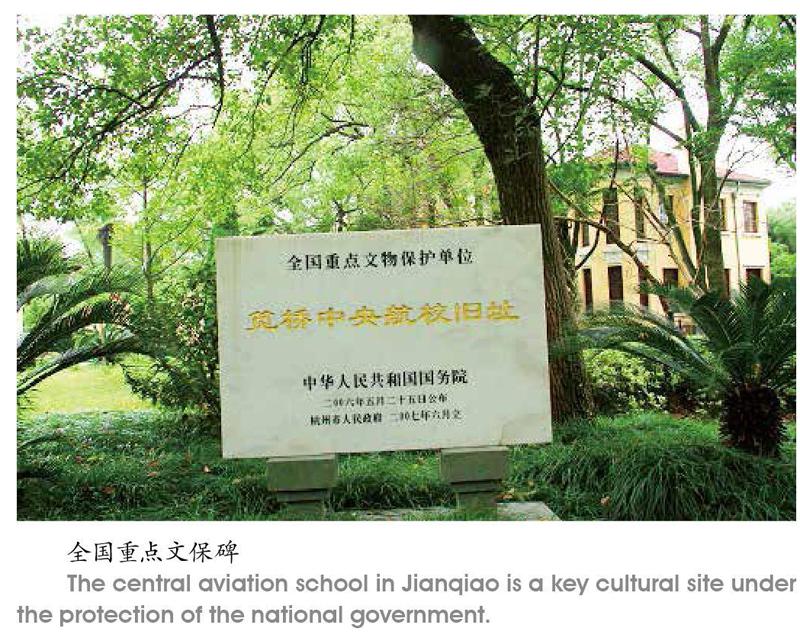

当时浙江档案馆有一批选题让我们去写,可以凭兴趣各自认领。我认领了“笕桥航校”的题目。因我之前先后淘过一本《笕桥英烈传》的同名影碟,想看看在版本和制式上有何异同,对此积累了一点兴趣。

几个月之后,在档案馆同志的帮助之下,我写成了关于笕桥中央航校的文章,在《都市快报》上发了4个版。一年后,一本叫《档案时空》的书在同事们的努力下也出版了。如果从工作的角度讲,我们的这个规定动作已经完成了。但是没想到,我竟然一头扎进了“笕桥航校”,且越走越远。我去了南京去了芷江去了腾冲,然后再去了台湾的冈山。我想获得更多的材料,我在台湾上网搜文史资料,发现我写笕桥航校的文字在那边的网上也都有,连我的小差错都原封不动地保留在那里,怎么让人不脸红呢?

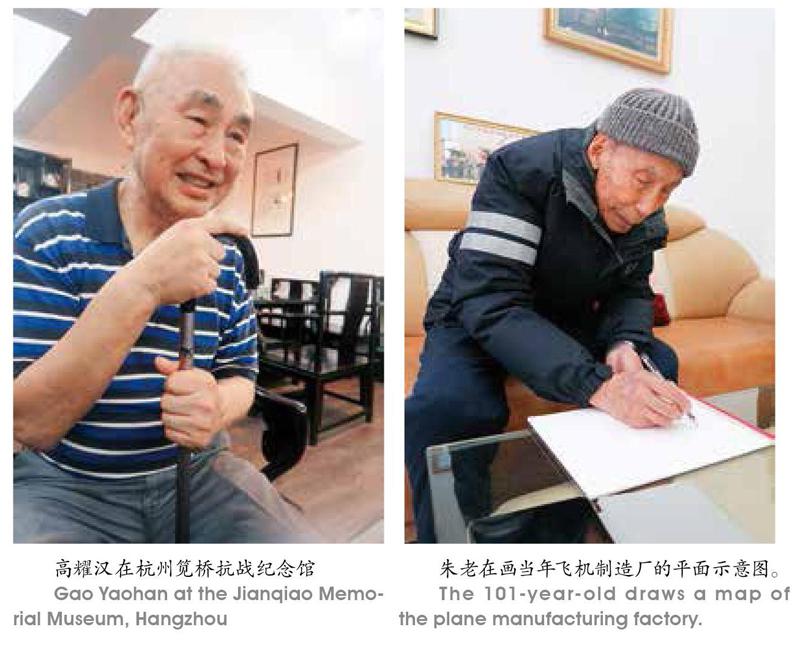

一开始我是相当孤陋寡闻的。我只知道笕桥有个航空学校,不知道一墙之隔还有个中央飞机制造厂。我在南京找到当年的学徒工、今年已经101岁的朱老先生,让他讲一讲他那个年代的生活,他眼里的航校战士。谁知他给我亲手绘了当年飞机厂的平面示意图,这是多么有意思的事情啊!两年后,在他百岁寿宴上,他率先起身致辞,祝在座的各位都要超过他,要长命百岁。去年秋天,他来杭州寻访他出生的地方,这让我们喜不自禁。8月14日那一天,他坚持自己一步一步走上南京航空烈士公墓的数百级台阶,手里拿着一束花,在烈日下站了半个多小时祭奠他的那些战友们。

话说杭州上空的“八一四”空战,之前我看到的材料上基本都是说我们打下了日本的6架飞机,我们却毫发无损。另一种表述是6比0完胜,但后来我看到在南京的航空纪念馆里说是4比0,有的地方又说是3比0……这可不是玩笑,怎么办呢?只有找更多的史料,找来自各方包括来自日本的史料,然后把这些史料一一列举出来,这样就可以自己判断了。后来我甚至看到有9比0的说法,还是在当年的空军最高长官、浙江临海人周至柔的文章中出现的。我跑到临海乡下去找他的故居,故居里真的没有什么了,但是找到了心就安了,正如我也在寻找他们说6比0乃至9比0的依据。

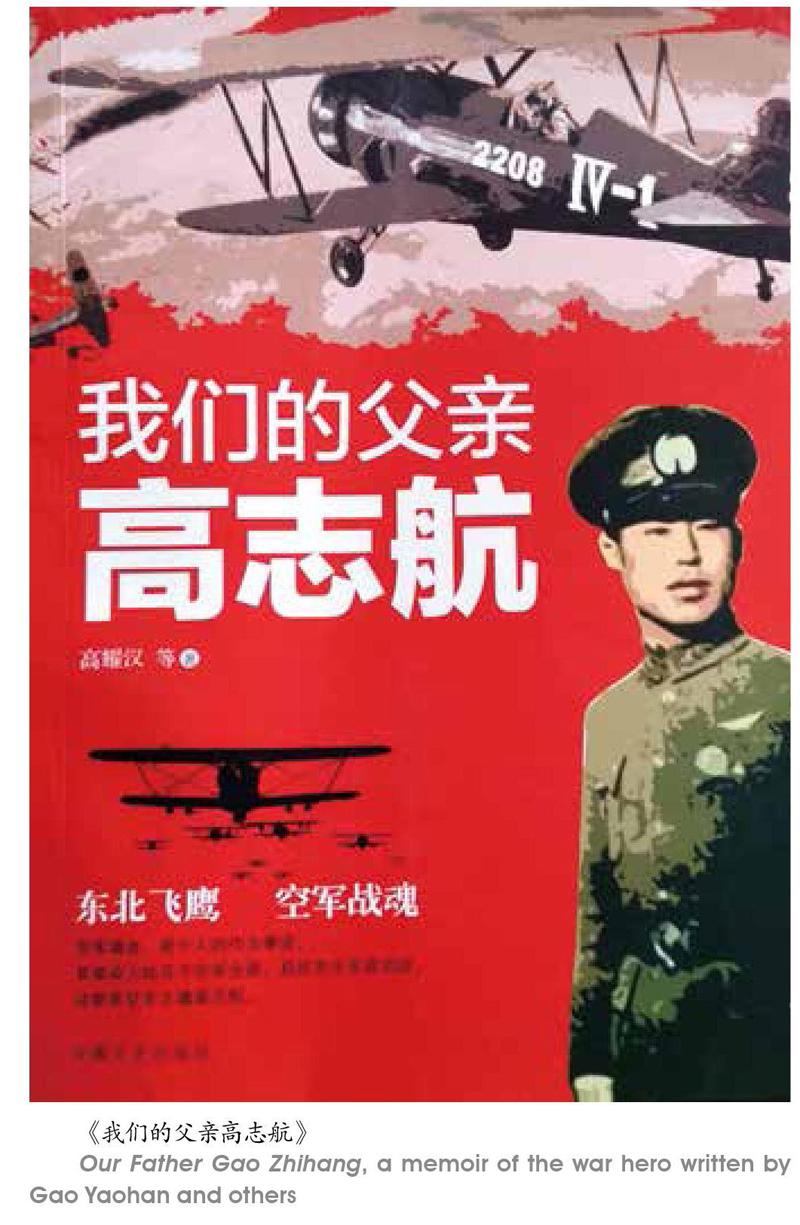

再比如高志航在“八一四”的第二天还在杭州上空跟日本人激战,又打下了敌机,但是他的手臂被日本飞行员用手枪射伤。我找到两本高志航的传记,一本说是左臂受伤,一本说是右臂受伤,到底是哪一只手臂?找到他在广济医院的照片,也看不清楚。包括我们的一些王牌飞行员,如刘粹刚到底打下了多少架日机,这在几种文本中也是不一样的。后来我才知道有时候是几个战友合力打下了一架,比如三个人同时开火的,但这样也只能说是击落了一架,而不能说是三架呀……我举这个例子只是想说明,如果你光写一个人一件事好像还不易出问题,但你要写一个团队,问题就出来了。你要给出一个答案,为了这个答案,你得找多少书啊,因为亲历者找不到了。

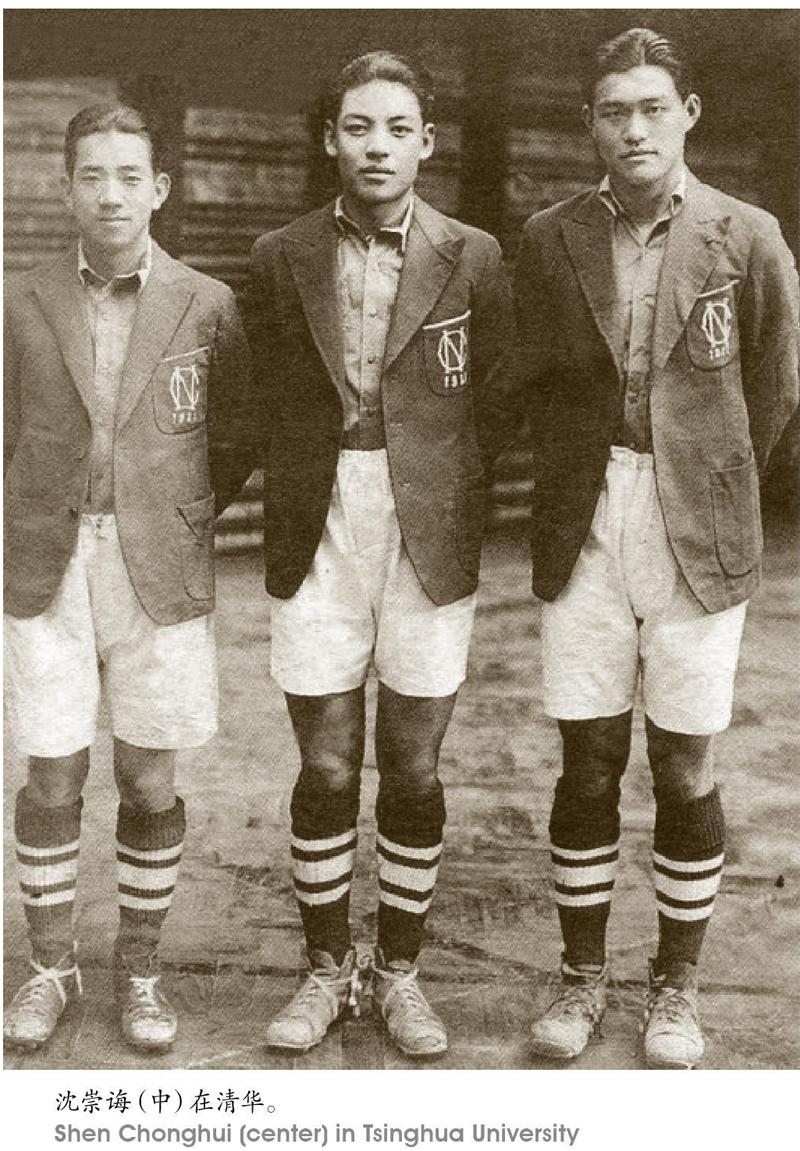

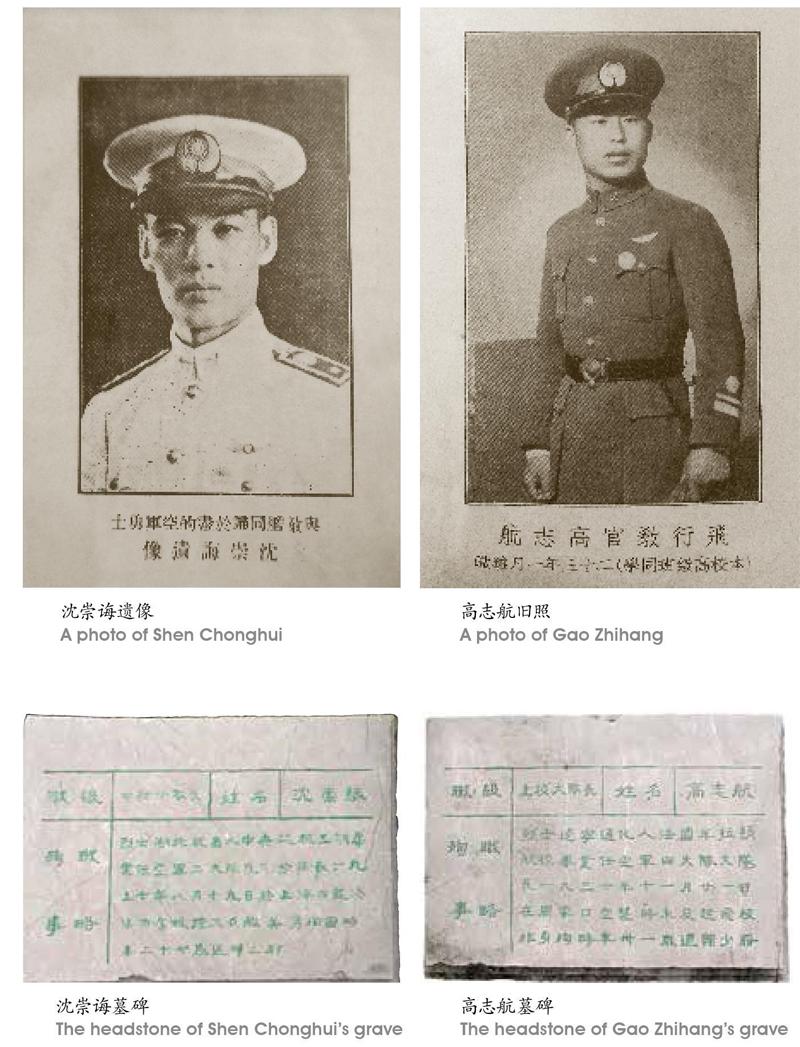

讲到电影《无问西东》中沈光耀的原型沈崇诲,我早就知道他是一名英雄,但那只是网上搜来的一点内容,不要说写书了,甚至都构不成一种谈资。2016年观看纪录片《冲天》时,我从浙江关爱抗战老兵志愿者吴缘那里知道了笕桥有一名收藏者在做航校的民间纪念馆,叫高建法,是笕桥本地人。于是我赶过去,为了去见大英雄高志航的儿子高耀汉。在那里竟然发现了沈崇诲他那班同学的纪念册,上面有他撰写的关于航校新生的调查报告,还有他的照片,后来又在三十年代的旧杂志《中国的空军》上发现了他的遗照。

我很早就在文字上看到過在杭州的梅东高桥有航校新生入伍训练营。那不就在杭州体育馆一带在我上班的地方吗?我从办公室的窗口望出去,可以看到沈崇诲们在操场上跑步。这个训练营到底在哪里?后因抗战全面爆发,笕桥航校也迁至云南。老杭州人都知道,这一带曾是清军的营盘,杭州沦陷后又曾是日本军队的营盘,民国时这体育场就是杭州飞机场的雏形,且也降落过飞机。后来杭州举办全国运动会,遂有了体育场路,并将大营盘一分为二,即一边是今天的体育场,一边是今天的体育馆……

当这些谜团被我一一破解的时候,我觉得我的快乐也跟“长命百岁”大约是相同的吧。

采访和写作很多时候也如同进入了山间,你本来是奔着什么大瀑布而去的,事实上可能连小龙湫都没有,但路边无名的野花却吸引住了你的眼光,然后再去网上搜索:这是什么花,这是什么草?南京的航空烈士陵园里,每一块墓碑都有一个故事,也都有多多少少的秘密,这些秘密有的在当年是公开的,有的直到今天还是秘密。比如说高志航的牺牲不是秘密,但他牺牲的消息是何时公布的?这直到今天我也还没有搞清楚,我想这就是我还暂时停不下来的原因之一。

俗话说踏破铁鞋无觅处,得来全不费功夫。踏破铁鞋是前提,而且有可能你踏遍青山之后人已经老了。我寻访抗战空军的第二代第三代,其中第三代中有不少也都比我年长了。我觉得最苦的是这些烈士们的后代,他们并不是说要为自己诉苦,而是要为他们的上一辈、为抗战老兵讨一个说法。

去年在南京参加纪念“八一四”空战80周年的活动时,我这一桌刚好有高志航留法同学的孙子和孙女在,还有一些起义投诚人员的子女,也有红色将领的子女,那种印象和感慨是我永远也不会忘的。当他们相逢一笑举起酒杯时,我突然又有了写作的冲动。

是啊,当年那些牺牲的空军战士太过年轻,平均年龄是23岁,他们就倒在抗战卫国的疆场上,有的瞬间就消失在天空中了。他们有的还没有成家,有的成家了也没有子女,不少有子女的则是遗腹子(女),这些子女今天最小的也70多岁了,实际上他们有的从没有见过自己的父亲。父亲只是在照片上,在文字的傳说里。在未亡人妻子那里,正如电视剧《一把青》中所讲的,飞行员的归零很简单,只是你的碎片,女人得去捡,你归零了,女人却要花一辈子的时间重新拼凑起来……这些抗战老兵的二代和三代,有的在做志愿者,比如在杭州的飞虎队员吴其轺的儿子吴缘可以说是倾其所有时间和精力都在为浙江的抗战老兵服务,这是令人感动和欣慰的。我的不少采访线索都是他提供的。

如果把时间坐标设定到抗战全面爆发的1937年,到今年已经81年过去了,当年的亲历者已经十分稀少了。我关注的又是空军,它的高牺牲率是人所皆知的。只能去寻找他们的第二代和第三代,活人找不到,只能去墓园里寻找碑文,这有不少后来也遭人为破坏,但所幸又有重修。

由于是在战争年代,空军的编队组织在当时也是军事机密,这使得当年的新闻报道有时也语焉不详。我看到关于沈崇诲牺牲的报道,最权威的是出自当年的空军刊物《中国的空军》,且不说年代久远字迹模糊,咬牙仔细读完发现那大半是散文诗风格,都是在歌颂其精神。今天的人提几个问题就会问倒我:他和同机战友的尸体有没有找到?被撞的出云舰到底受了多大的伤?他有没有女朋友?日本报纸有没有对此报道过?这恰恰都是我要去破解的。也许不能叫破解,只是去寻找,尽可能地去逼近或还原事实本身,无问西东,无问结果。这需要一种路径,一种方式,一种默默前行的勇气。

正如李宗盛在歌中所唱的:越过山丘,才发现无人等候。而我要说:越过山丘,我看到天空在向我招手。

At the end of the movie , Shen Guangyao (played by Leehom Wang) steers his plane towards the Japanese warship. At that moment, he sees his comrade parachuting from the sky into the shooting range of a Japanese pilot…

At that moment, I figured out what the film was trying to convey and realized who the prototypes of the characters were. At that moment, I could even tell the difference between the sky in Yunnan and that in Hangzhou.

The realization stemmed from , a non-fiction I had written a few years before. It all started from a writing project commissioned by Zhejiang Archives. I chose the Chinese air force as the subject just because of a movie I had happened to watch. The writing of a cycle of articles about the Jianqiao Central Aviation School in Hangzhou took several months to complete. The articles got published in a local daily newspaper, followed by a book released a year later. My share of the mission seemed to be completed, but it turned out to be the start of my ‘Jianqiao Expedition that has reshaped my mentality as a writer and story-teller.

To find more about the aviation school in Jianqiao, I went to Nanjing, Zhijiang, Tengchong and Gangshan (in Taiwan) in search of historical details and witnesses of the schools past. In Nanjing I met Mr. Zhu, who worked at the plane factory of the school when he was young. I came home with a sketch map of the school hand-drawn by the 101-year-old. Last year, the man visited Hangzhou to seek his roots. On August 14, he went to see his comrades resting in peace at the Nanjing Aviation Martyrs Cemetery, carrying a bouquet of flowers in his hands.

For me, the process of digging into the past to get to the root of the matter turned out to be more rewarding than the success of the writing project. In order to get as closer to the truth about the ‘8.14 air battle in Hangzhou in 1937 as possible, I went to try my luck in the former residence of Zhou Zhirou in the outskirts of Linhai, Taizhou. The result of the war was mentioned in one of his articles by the chief commander. There was nothing to see in the house, but I came home feeling like a puzzle was solved.

One of the heroes in the ‘8.14 battle was Gao Zhihang, whose arm got shot when he was combating the Japanese in the high air. To find out which arm of his was wounded, I went out of my way to find a picture that shows the man in a hospital in Hangzhou, although the picture fails to give a clear answer.

The more I dug into the war past of Hangzhou, the more questions I felt duty-bound to clarify and answer. There were numerous details to figure out. Without the help of the recounts of witnesses, all I could do was to look for needles in a bundle of hay. Whats more, writing about a team instead of an individual added a lot to the difficulty of the task.

The prototype of Shen Guangyao is Shen Chonghui, about whom I knew too little to write a brief introduction, not to mention a book. In 2016, I learned from a documentary about Gao Jianfa, a Jianqiao native who was at that time working on a museum dedicated to the aviation school. I visited him, in hope of meeting the son of one of the ‘8.14 heroes. Much to my surprise, in the mans place I found a yearbook that contained valuable information about Shen Chonghui and a picture of him.

The aviation school in Jianqiao relocated to Yunnan after Chinas war of resistance against Japanese aggression officially broke out. Looking out of the window of my working place on todays Tiyuchang Road in downtown Hangzhou, I can feel the historical weight of this part of Hangzhou as if I went through the war flames together with the aviation heroes. Where a section of Tiyuchang Road is today was once known as Big Barracks, a military base of the Qing Dynasty. It later served as a military airport in the Republican years and it was turned into a Japanese military camp after the fall of Hangzhou.

My Jianqiao Expedition has given me a lot. One of the things I have learned is, writing and meeting people feels like walking into the depths of the mountain to see waterfalls. One often winds up seeing nothing at all. However, it is not a wild goose chase, for nameless roadside flowers always turn out to be worth exploring and admiring. Behind every tomb at the martyrs cemetery in Nanjing, there is a story untold. Some of them will be known by the whole world; some will remain secrets forever.