春季黄、渤海中异戊二烯的浓度空间分布与海-气通量

吴英璀,李建龙,王 健,张洪海,杨桂朋,2

春季黄、渤海中异戊二烯的浓度空间分布与海-气通量

吴英璀1,李建龙1,王 健1,张洪海1*,杨桂朋1,2

(1.中国海洋大学化学化工学院,山东 青岛 266100;2.青岛海洋科学与技术国家实验室,海洋生态与环境科学功能实验室,山东 青岛 266071)

利用吹扫捕集-气质联用方法测定了2014年5月黄海、渤海所取海水样品中异戊二烯的含量,探讨了其分布特征、海-气通量及影响因素.研究结果表明:春季黄海、渤海海域表层海水中异戊二烯的浓度范围为6.02~32.91pmol/L,(平均值±标准偏差)为(15.39±4.98) pmol/L,在黄海中部海域出现浓度高值;表层海水中异戊二烯与叶绿素(Chl-)浓度有一定的正相关性(2= 0.2529,= 49,< 0.001),说明浮游植物生物量在异戊二烯生产和分布中发挥重要作用;春季黄海、渤海异戊二烯海-气通量的变化范围为0.78~192.43nmol/(m2·d),(平均值±标准偏差)为(24.08±30.11)nmol/(m2·d),表明我国陆架海区是大气异戊二烯重要的源.

异戊二烯;分布特征;海-气通量;黄海;渤海

非甲烷烃是大气中一类重要的痕量活性气体,是参与全球碳循环的重要物质.海洋作为大气中NMHCs的一个重要来源,其每年向大气的排放量约为2~50Tg C/a[1].进入大气中的NMHCs会与对流层中羟基自由基(OH)等发生反应,进而影响对流层的氧化能力,间接影响大气平衡[2-3].此外,NMHCs对于臭氧(O3)的产生与消除以及二次气溶胶的形成也具有非常重要的作用[4-7].异戊二烯作为NMHCs中含量最丰富、最重要的一种组成成分,对全球气候变化具有重要的影响[8].海水中异戊二烯的来源包括浮游植物产生[9]和直接合成[10-12]两种途径.另外表层海水中溶解有机物的光化学降解[13-15]也是海水中异戊二烯重要的非生物来源.异戊二烯一旦被产生,很容易被各种途径去除,如微生物消耗、光化学氧化[11,16]和释放到大气中去.然而,研究表明海-气扩散是海水中异戊二烯的主要去除途径[17-18],经估算由海洋释放至大气中的异戊二烯的年平均释放量可达0.31~1.09Tg C/a[1].因此,开展关于海水中异戊二烯生产、分布及海-气通量的研究对于更进一步认识全球碳循环及气候变化意义重大.

近年来,国外有关异戊二烯已开展大量研究,但调查区域多集中于大洋开阔海域,陆架、近岸海域研究甚少.目前,我国鲜见关于海洋异戊二烯的研究,只有李建龙等[19]对秋季黄海、渤海异戊二烯浓度分布等进行了初步探索.黄海、渤海作为西北太平洋的边缘海,二者相连并且充分交换,是世界上最具代表性的大陆架海区之一.该海区处于渤海沿岸流、黄海沿岸流、黄海暖流等综合作用区,复杂的水文条件会对海洋生源异戊二烯的生产、分布产生重要的影响.因此,本文对春季黄海、渤海表层海水中的异戊二烯的浓度空间分布和影响因素进行了研究,计算了异戊二烯的海-气通量,旨在了解春季黄海、渤海异戊二烯的空间分布特征,并讨论异戊二烯与环境因子的相互关系,以期为深入地认识中国海域生源异戊二烯的生物地球化学循环和气候效应具有重要的科学意义.

1 样品采集与分析

1.1 样品采集

于2014年5月2~ 20日(春季)搭载“东方红2号”科学调查船对中国黄海、渤海海域进行调查研究,调查站位如图1所示.本航次采样范围覆盖116°~128°E、30°~40°N之间的海域,包括52个站位.现场采用12-L Niskin Rosette采水器采集海水样品,水样引入120mL棕色试剂瓶,润洗2次.注入过程应避免气泡和涡流的存在,待水满溢出大约玻璃瓶体积的1/3后,滴加2滴饱和的HgCl2溶液以抑制生物活动和潜在的降解作用[20-21],用带聚四氟乙烯衬垫的铝盖压盖密封,在4℃条件下避光保存.研究表明,此条件下,样品可保存两个月以上[22],但为了分析结果的可靠性和准确性,采集的样品待返回陆地实验室应尽快完成测定.现场海水的温度、盐度等环境参数均由温盐深仪(CTD,Seabird 911plus,美国Sea-Bird Scientific公司)在采集海水时同步测定完成,同时现场气温、气压、风速等海洋气象参数是由船载的气象观测仪(Young公司,美国)进行测定.

图1 黄海、渤海海域调查站位

1.2 样品分析方法

利用吹扫捕集-气质联用方法分析天然海水中的痕量异戊二烯[23-24].分析过程如下:六通阀在捕集状态下,将100mL水样用气密性良好的注射器注入气提室,高纯N2鼓泡将水样中的异戊二烯吹出,先后经过装有无水Mg(ClO4)2的干燥管和装有固体NaOH的玻璃管分别进行干燥和CO2去除,后进入浸泡在液氮(-178℃)的不锈钢捕集管进行富集.富集过程结束后,关闭吹扫N2,将不锈钢捕集管迅速放入沸水(100℃)中加热解析,同时将六通阀切换到进样状态,用高纯He将解析出来的气体组分送入GC分离后,最后经MS检测分析.

1.3 叶绿素a (Chl-a)含量的测定

海水样品采集后,使用孔径0.70μm Whatman GF/F玻璃纤维滤膜在低压(<15kPa)条件下过滤300mL海水样品.过滤完成后,滤膜对折,并用锡纸包好冷冻(-20℃)保存[25].待回到陆地实验室后,采用荧光法[26]测定Chl-的含量.

1.4 海-气通量的计算方法

异戊二烯的海-气通量由如下公式计算:

=L· △

式中:为海-气通量,nmol/(m2·d);L为气体交换常数,m/d;

△= (W–H×I)

式中:W为表层海水中异戊二烯的浓度, pmol/L;I为异戊二烯分压;H为亨利常数,取2.67× 10-7mol/(L·Pa)[27].由于航次执行时的条件限制,没有同步测定大气中异戊二烯的浓度,因此本论文采用与调查海域纬度相近的日本近海海域测定的大气中异戊二烯的浓度(5×10-11)[28]对该航次的异戊二烯海-气通量进行估算.

L根据Wanninkhof[29]模型计算:

L= 2.778 × 10-6[0.312(C/ 660)-1/2]

式中:为水面上方10m处的风速,m/s;C为施密特常数,对于特定气体而言,C主要与物质的相对分子质量和水体温度等参数有关.

C根据Palmer and Shaw (2005)[30]计算:

C= 3913.15 – 162.13+ 2.672– 0.0123

式中:为海水温度,℃

采用Excel 2007软件进行数据计算及处理,采用ODV4、Surfer 11和Origin 8.0软件绘图.

2 结果与讨论

2.1 表层海水中异戊二烯的水平分布特征

春季黄海、渤海表层海水中盐度、温度、Chl-和异戊二烯的水平分布如图2所示.由图2可以看出,黄海海域海水的温度和盐度均呈现由东南向西北递减的趋势,这主要是由于来自黑潮水系的黄海暖流沿济州岛以西海域入侵黄海,导致黄海东部海域温度和盐度明显高于其他调查海域.此外因为受到鸭绿江、黄河、长江等陆源输入的影响,调查海域的盐度由近岸向远岸逐渐降低.春季黄海、渤海表层海水中Chl-的浓度变化范围介于0.38~3.74µg/L之间,(平均值±标准偏差)为(1.59±0.79)µg/L.Chl-浓度最高值(3.74µg/L)和次高值(3.70µg/L)分别出现在南黄海中央调查海域的H28和H23站位,由Chl-的水平分布图可以看出,在南黄海中央海域存在一Chl-浓度高值区,其浓度明显高于江苏、山东等近岸海域,如江苏近岸海域的H19 (1.05µg/L)站位、山东近岸海域的B07 (1.56µg/L)站位,这主要是由于调查期间南黄海中央海域处于春季藻华期,浮游植物细胞丰度较高[31],导致此区域Chl-的浓度较大.此外,5月(晚春)在偏南风的影响下,长江冲淡水开始由南向北偏转,将营养盐向黄海中南部输送[32],因此该区域充足的营养盐供给和适宜的海水温度促进浮游植物的生长,从而导致了该附近海域生产力水平比较高.

调查海域表层海水中的异戊二烯的浓度变化范围为6.02~32.91pmol/L,(平均值±标准偏差)为(15.39 ± 4.98) pmol/L.南黄海中央海域存在明显的异戊二烯浓度高值区,并且与Chl-的浓度高值区相对应,这可能与调查期间该海域存在较大范围的“藻华”事件有关.其中发生藻华站位的异戊二烯的浓度大多超过20pmol/L,并且异戊二烯的浓度最高值(32.91pmol/L)和次高值(30.25pmol/L)分别出现在南黄海的H28和H23站位,与Chl-的浓度高值一致,进一步说明研究海域的异戊二烯主要来源于浮游植物的直接释放[9,33-34].

2.2 异戊二烯与Chl-a之间的相互关系

海洋中的异戊二烯是由浮游植物、异养细菌和海草释放产生[28,35],其中浮游植物是主要的贡献者,其含量与调查区域初级生产力水平关系密切,而Chl-常被作为海洋浮游植物生物量的一个重要指标[36],能客观地反映调查区域的初级生产力水平.为探讨浮游植物与异戊二烯之间的关系,对2014年5月春季黄海、渤海调查海域表层海水中异戊二烯与Chl-进行相关性分析.如图3所示,春季黄海、渤海表层海水中异戊二烯与Chl-表现出一定的正相关关系(2= 0.2529,= 49,<0.001),表明浮游植物释放是海洋异戊二烯的重要来源,其浮游植物生物量对黄海、渤海海域异戊二烯的生产和浓度分布具有重要影响,这与Kurihara等[21]的研究结果一致.

由于调查海域范围内浮游植物种类及组成存在较大差异,不同浮游植物对异戊二烯和Chl-的生产贡献存在明显区别,从而导致异戊二烯与Chl-的相关性并不十分明显.此外,海区光照辐射条件、有机物的降解过程等因素[37]也会对异戊二烯产生一定的影响.

图3 黄渤海表层海水中异戊二烯与Chl-a之间的相关性

2.3 黄海、渤海海域表层海水中异戊二烯浓度的季节对比

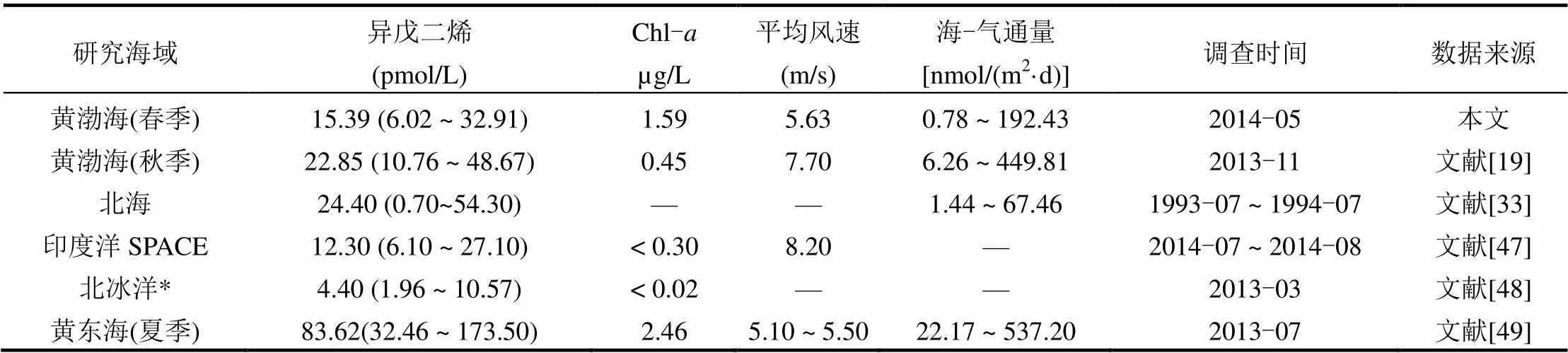

表1列出了不同海域表层海水中异戊二烯的浓度调查结果,显示异戊二烯在近海和大洋中普遍存在.由于不同调查海域浮游植物的生物量以及物种组成存在差异[13,33],导致海水中异戊二烯的浓度具有一定的差异性.从表1可以看出,浮游植物生物量较高(Chl-浓度较大)的陆架海域贡献出较高的异戊二烯浓度,说明浮游植物生物量对海区内异戊二烯浓度有重要影响.此外,对比春、秋两季黄海、渤海海域的调查结果,春季表层海水中异戊二烯的浓度(15.39±4.98)pmol/L明显低于秋季(22.85±10.82)pmol/L,但春季Chl-的平均浓度[(1.59±0.79)µg/L]却高于秋季[(0.45 ±0.25)µg/L],这可能是由于不同季节浮游植物的种类不同[13,33],对Chl-和表层海水中异戊二烯的贡献存在较大差异所致.研究表明,硅藻和甲藻是春季黄渤海表层海水中浮游植物群落的优势藻种[38-42],而且多种硅藻和甲藻都可以产生异戊二烯[11,43-44].春季黄渤海表层海水中的硅藻、甲藻种类低于秋季[45-46],即优势种在浮游植物丰度中的比例更高,但它们对异戊二烯的产量贡献可能却相对较低,这可能是春季黄渤海表层海水中Chl-浓度高于秋季,异戊二烯的浓度低于秋季的重要原因.然而,有关不同藻类对异戊二烯释放量影响的文献报道相对较少,因此在以后的研究中有待加强.

表1 不同海域表层海水中异戊二烯的海-气通量对比

注: “—”为未检测, SPACE:印度洋调查航次的第一航段(Science Partnerships for the Assessment of Complex Earth System Processes)北冰洋*: ACCACIA 1cruise.

2.4 异戊二烯的海-气通量

表1列出了不同海域的异戊二烯的海-气通量的调查结果,发现春季黄海、渤海的海-气通量介于(0.78~192.43)nmol/(m2·d)之间,(平均值±标准偏差)为(24.08±30.11)nmol/(m2·d);最大值出现在H01站位,风速(19.8m/s)也较大;最小值出现在B31站位,该站位的风速(1.2m/s)较低.该研究结果明显低于李建龙等[19]观测的秋季黄海、渤海的海-气通量平均值(91.62±109.75)nmol/(m2·d),这主要是由于秋季黄渤海表层海水中异戊二烯的平均浓度(22.85±10.52)pmol/L高于春季航次的调查结果(15.39±4.98)pmol/L.此外,秋季航次调查期间的风速(平均风速7.70m/s)较春季航次(平均风速5.63m/s)高,进而导致异戊二烯的海-气释放增加.将本研究结果与其他近岸海域[19,48]异戊二烯的海-气通量的研究结果进行比较,发现该调查海域的海-气通量与其它近岸海域相比结果相当且均为正值,这表明生产力水平较高的近岸陆架海域是大气中异戊二烯的重要来源之一[19].

3 结论

3.1 春季黄海、渤海的表层海水中异戊二烯在南黄海中央海域出现浓度高值区,其浓度明显高于江苏、山东近岸等海域,这应该是受到春季藻华的影响;

3.2 表层海水中异戊二烯与Chl-呈一定的正相关性,说明浮游植物在影响异戊二烯生产和分布中发挥重要作用;

3.3 春季黄海、渤海海域表层海水中的异戊二烯的海-气通量较大,且与其他近岸海域的海-气通量结果相当,表明近岸陆架海域是大气中异戊二烯的重要来源之一.

[1] Tran S, Bonsang B, Gros V, et al. A survey of carbon monoxide and non-methane hydrocarbons in the Arctic Ocean during summer 2010: assessment of the role of phytoplankton [J]. Biogeosciences Discussions, 2013,10(3):1909-1935.

[2] Pszenny A A P, Prinn R G, Kleiman G, et al. Nonmethane hydrocarbons in surface waters, their sea-air fluxes and impact on OH in the marine boundary layer during the first Aerosol Characterization Experiment (ACE 1) [J]. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 1999,104(D17):21785-21801.

[3] Hellen H, Hakola H, Laurila T. Determination of source contributions of NMHCs in Helsinki (60°N, 25°E) using chemical mass balance and the Unmix multivariate receptor models [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2003,37:1413-1424.

[4] Poisson N, Kanakidou M, Crutzen P J. Impact of non-methane hydrocarbons on tropospheric chemistry and the oxidizing power of the global troposphere: 3-dimensional modelling results [J]. Journal of Atmospheric Chemistry, 2000,36(2):157-230.

[5] Sahu L K, Lal S. Distributions of C2-C5NMHCs and related trace gases at a tropical urban site in India [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2006,40:880-891.

[6] Liakakou E, Bonsang B, Williams J, et al. C2-C8NMHCs over the Eastern Mediterranean:Seasonal variation and impact on regional oxidation chemistry [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2009,43: 5611-5621.

[7] Al Madhoun W A, Ramli N A, Yahaya A S, et al. Temporal distribution of non-methane hydrocarbon (NMHC) in a developing equatorial island [J]. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health, 2015:1-8.

[8] Zeng G, Pyle J A. Changes in tropospheric ozone between 2000 and 2100 modeled in a chemistry-climate model [J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2003,30(7):1392.

[9] Colomb A, Yassaa N, Williams J, et al. Screening volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emissions from five marine phytoplankton species by head space gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (HS-GC/MS) [J]. Journal of Environmental Monitoring Jem, 2008,10(3):325-30.

[10] Korhonen H, Carslaw K S, Spracklen D V, et al. Influence of oceanic dimethyl sulfide emissions on cloud condensation nuclei concentrations and seasonality over the remote Southern Hemisphere oceans: A global model study [J]. Journal of Geophysical Research, 2008,113(113):99-119.

[11] Milne P J, Riemer D D, Zika R G, et al. Measurement of vertical distribution of isoprene in surface seawater, its chemical fate, and its emission from several phytoplankton monocultures [J]. Marine Chemistry, 1995,48(3/4):237-244.

[12] 赵 静,张桂玲.大气和海水中非甲烷烃类的研究进展[J]. 浙江海洋学院学报(自然科学版), 2009,28(2):205-213.

[13] Shaw S L, Chisholm S W, Prinn R G. Isoprene production by Prochlorococcus, a marine cyanobacterium, and other phytoplankton [J]. Marine Chemistry, 2003,80(4):227-245.

[14] Kuzma J, Nemecekmarshall M, Pollock W H, et al. Bacteria produce the volatile hydrocarbon isoprene [J]. Current Microbiology, 1995,30(2):97-103.

[15] Druffel E R M, Williams P M, Bauer J E, et al. Cycling of dissolved and particulate organic matter in the open ocean [J]. Journal of Geophysical Research Oceans, 1992,97(C10):15639- 15659.

[16] Ratte M, Bujok O, Spitzy A, et al. Photochemical alkene formation in seawater from dissolved organic carbon: Results from laboratory experiments [J]. Journal of Geophysical Research Atmospheres, 1998,103(D5):5707-5717.

[17] Brian H, Meehye L, Robert T, et al. Ozone, hydroperoxides, oxides of nitrogen, and hydrocarbon budgets in the marine boundary layer over the South Atlantic [J]. Journal of Geophysical Research Atmospheres, 1996,1012(19):24221- 24234.

[18] Donahue N M, Prinn R G. Nonmethane hydrocarbon chemistry in the remote marine boundary layer [J]. Journal of Geophysical Research Atmospheres, 1990,95(D11):18387–18411.

[19] 李建龙,周立敏,张洪海,等.秋季黄海与渤海异戊二烯含量的分布及海-气通量[J]. 环境科学研究, 2015,28(7):1062-1068.

[20] Matsunaga S, Mochida M, Saito T, et al. In situ measurement of isoprene in the marine air and surface seawater from the western North Pacific [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2002,36:6051-6057.

[21] Kurihara M, Iseda M, Ioriya T, et al. Brominated methane compounds and isoprene in surface seawater of Sagami Bay: Concentrations, fluxes, and relationships with phytoplankton assemblages [J]. Marine Chemistry, 2012,134-135(8):71-79.

[22] 张洪海,李建龙,杨桂朋,等.吹扫捕集-气相色谱-质谱联用测定天然水体中异戊二烯的研究[J]. 分析化学, 2015,(3):333-337.

[23] Baker B, Johnson B C, Cai Z T, et al. Wet and dry season ecosystem level fluxes of isoprene and monoterpenes from a southeast Asian secondary forest and rubber tree plantation [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2005,39(2):381-390.

[24] Yang G P, Xiao-Lan L U, Song G S, et al. Purge-and-Trap Gas Chromatography Method for Analysis of Methyl Chloride and Methyl Bromide in Seawater [J]. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 2010,38(5):719-722.

[25] 孙 婧,张洪海,张升辉,等.夏季东海生源硫的分布、通量及其对非海盐硫酸盐的贡献[J]. 中国环境科学, 2016,36(11):3456- 3464.

[26] 张洪海,杨桂朋.胶州湾及青岛近海微表层与次表层中二甲基硫(DMS)与二甲巯基丙酸(DMSP)的浓度分布[J]. 海洋与湖沼, 2010,41(5):683-691.

[27] Chameides W L, Fehsenfeld F, Rodgers M O, et al. Ozone precursor relationships in the ambient atmosphere [J]. Journal of Geophysical Research Atmospheres, 1992,97(D5):6037–6055.

[28] Yokouchi Y, Li H J, Machida T. Isoprene in the marine boundary layer (Southeast Asian Sea,eastern Indian Ocean,and southern Ocean): comparison with dimethyl sulfide and bromoform [J]. Journal of Geophysical Research, 1999,104(7):8067-8076.

[29] Wanninkhof R. Relationship between wind speed and gas exchange over the ocean [J]. Journal of Geophysical Research Oceans, 1992,97(C5):7373-7382.

[30] Palmer P I, Shaw S L. Quantifying global marine isoprene fluxes using MODIS chlorophyll observations [J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2005,32(32):302-317.

[31] 胡好国,万振文,袁业立.南黄海浮游植物季节性变化的数值模拟与影响因子分析[J]. 海洋学报, 2004,26(6):74-88.

[32] 王保栋.黄海和东海营养盐分布及其对浮游植物的限制[J]. 应用生态学报, 2003,14(7):1122-1126.

[33] Broadgate W J, Liss P S, Penkett S A. Seasonal emissions of isoprene and other reactive hydrocarbon gases from the ocean [J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 1997,24(21):2675-2678.

[34] Lewis A C, Carpenter L J, Pilling M J. Nonmethane hydrocarbons in Southern Ocean boundary layer air [J]. Journal of Geophysical Research, 2002,36(20):3217-3229.

[35] Carpenter L J, Archer S D, Beale R. Ocean-atmosphere trace gas exchange [J]. Chemical Society Reviews, 2012,41(19):6473.

[36] 邹景忠,董丽萍,秦保平.渤海湾富营养化和赤潮问题的初步探讨[J]. 海洋环境科学, 1983,(2):45-58.

[37] Riemer D D, Milne P J, Zika R G, et al. Photoproduction of nonmethane hydrocarbons (NMHCs) in seawater [J]. Marine Chemistry, 2000,71(3):177-198.

[38] 孙 军,东 艳,徐 俊,等.1999年春季渤海中部及其邻近海域的网采浮游植物群落[J]. 生态学报, 2004,24(9):2003-2016.

[39] 刘素娟,李清雪,陶建华.渤海湾浮游植物的生态研究[J]. 环境科学与技术, 2007,30(11):4-6.

[40] 王 俊.黄海春季浮游植物的调查研究[J]. 渔业科学进展, 2001,22(1):56-61.

[41] 张 珊,冷晓云,冯媛媛,等.春季黄海浮游植物生态分区:物种组成[J]. 海洋学报:中文版, 2015,35(8).

[42] 田 伟.黄海中部春季浮游植物水华群落结构及演替[D]. 中国海洋大学, 2011.

[43] Moore R M, Oram D E, Penkett S A. Production of isoprene by marine phytoplankton cultures. Geophysical Research Letters, 1994,21(23):2507-2510.

[44] Mckay W A, Turner M F, Jones B M R, et al. Emissions of hydrocarbons from marine phytoplankton—Some results from controlled laboratory experiments [J]. Atmospheric Environment.

[45] 王 俊.渤海近岸浮游植物种类组成及其数量变动的研究[J].渔业科学进展, 2003,24(4):44-50.

[46] 刘述锡,樊景凤,王真良,等.北黄海浮游植物群落季节变化[J]. 生态环境学报, 2013,(7):1173-1181.

[47] Booge D, Schlundt C, Bracher A, et al. Marine isoprene production and consumption in the mixed layer of the surface ocean – A field study over 2oceanic regions [J]. Biogeosciences Discussions, 2017:1-28.

[48] Hackenberg, S. C, Andrews, S. J, Airs, R, et al. Potential controls of isoprene in the surface ocean [J]. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 2017,31(4).

[49] Li J L, Zhang H H, Yang G P. Distribution and sea-to-air flux of isoprene in the East China Sea and the South Yellow Sea during summer [J]. Chemosphere, 2017,178:291.

Spatial distribution and sea-to-air flux of isoprene concentration in the Yellow Sea and the Bohai Sea in spring.

WU Ying-cui1, LI Jian-long1, WANG Jian1, ZHANG Hong-hai1*, YANG Gui-peng1,2

(1.College of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266100, China;2.Laboratory for Marine Ecology and Chemistry and Environmental Science, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266071, China)., 2018,38(3):893~899

Isoprene concentrations were determined by gas chromatography with mass spectrum detector (GC-MSD) coupled with purge-and-trap system to study the spatial distribution as well as sea-to-air flux and influencing factors. The results showed that the concentrations of isoprene ranged from 6.02 to 32.91pmol/L in the surface seawater of the Yellow Sea and the Bohai Sea in spring, with an average of (15.39 ± 4.98) pmol/L. The highest concentration of isoprene was found in central Yellow Sea. A positive correlation was observed between isoprene and Chl-concentrations (2= 0.2529,= 49,< 0.001), suggesting that phytoplankton play an important role in the production and distribution of isoprene. The sea-to-air flux ranged from 0.78 to 192.43nmol/(m2·d), with a mean value of (24.08 ± 30.11) nmol/(m2·d). The study shows that the shelf seas of China might be an important source of isoprene.

isoprene;distribution;sea-to-air flux;Yellow Sea;Bohai Sea

X511,X55

A

1000-6923(2018)03-0893-07

吴英璀(1993-),女,山东东营人,中国海洋大学化学化工学院硕士研究生,主要从事海洋异戊二烯分布与通量的研究.

2017-08-07

国家重点研发计划项目(2016YFA0601301);国家自然科学基金(41306069);中国科学院海洋研究所海洋生态与环境科学重点实验室开放基金(KLMEES201602);中央高校基本科研业务费项目(201513049)

* 责任作者, 副教授, honghaizhang@ouc.edu.cn