Some progress on understanding the Phanerozoic granitoids in China

To Wng, Ying Tong, Xio-xi Wng, Jin-ren Mo, Hong-rui Zhng, He Hung, Shn Li, b,Lei Guo, Jin-jun Zhng

a Key Laboratory of Deep-Earth Dynamics, Ministry of Natural Resources, Beijing 100037, China

b Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing 100037, China

c Key Laboratory of Metallogeny and Mineral Assessment of Ministry of Natural Resources, Institute of Mineral Resources, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing 100037, China

d Nanjing center, China Geological Survey, Nanjing 210016, China

A B S T R A C T

There are large volumes of the Phanerozoic granitoid rocks in China and neighboring areas. In recent years, numerous new and precise U-Pb zircon ages have been published for these granitoids, and define many important magmatic events, such as ca. 500 Ma granitoid events in the West Junggar, Altai orogens in the NW China, and Qinling orogen in the central China. These ages accurately constrain the time of important Early Paleozoic, Late Paleozoic, Early Mesozoic and Late Mesozoic magmatic events of the northern, central, western, southern and eastern orogenic Mountains in China. There occur various types of granitoids in China, such as calc-alkaline granite, alkali granite, highly-fractionated granite, leucogranite,adakite, and rapakivi granite. Rapakivi granites are not only typical Proterozoic as in the North China Craton, but were also emplaced during Paleozoic and Mesozoic in the Kunlun-Qinling orogen, a part of the China Central Orogenic Belt (CCOB). Nd-Hf isotopic tracing and mapping show that granitoids in the southern Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB) in China (or the Northern China Orogenic Belt) are characterized predominantly by juvenile sources.The juvenile crust in this orogenic domain accounts for over 50% by area, distinguishing it from other orogenic belts in the world, and those in central (e.g., Qinling), southwestern and eastern China. Based on a large amount of new age data, a preliminary granitoid and granitoid-tectonic maps of China have been preliminarily compiled, and an evolutionary framework of Phanerozoic granitoids in China and neighboring areas has been established from the view of assembly and breakup of continental blocks. Research ideas on granitoid tectonics has also been proposed and discussed.

Keywords:

Granitoids

Zircon age

Spatial-temporal distribution

Radiogenic isotopes

Orogen

1. Introduction

The term “granitoids” mentioned in this paper is generalized, referring to granitoid rocks. This is the most widespread rock type in the Earth’s continental crust and is distinct on Earth compared to other planets, and it is also the most remarkable characteristic of the continental crust. Granitoids form in various geodynamic settings, and record information on magma-formation and emplacement, tectonics, mineralization, crust-mantle interaction, and continental growth as well as on assembly and breakup of continental blocks. Granitoids are one of the most important objects for the study of continental geodynamics.

China, and Asia as a whole, is one of the largest areas with granitoid occurrences on the earth, and large volumes of granitoids developed from Archean to Cenozoic and in various tectonic settings. These granitoids are closely related to the tectonic evolution and are sites of important mineralization (Hong DW et al., 2007). In recent years, research on the origin and evolution of granitoids in China has made remarkable progress and it is impossible to completely cover all achievements in this review. Therefore, this paper only summarizes some research progress on Phanerozoic granitoids, allowing the reader to better understand and get some characteristics and new data on granitoids in China.

2. Geochronological framework and spatial-temporal evolution of large granitoids areas

During the last decade or so, one of the outstanding ach-ievements in granite research was the large amount of high precision zircon ages. These resulted in revision and rebuilding of granite chronology and magmatic evolution models in critical areas of orogens in China and surrounding areas, revealing the processes of magma formation and evolution of large granitoids areas.

2.1. Granitoids in the southern Central Asian Orogenic Belt of China

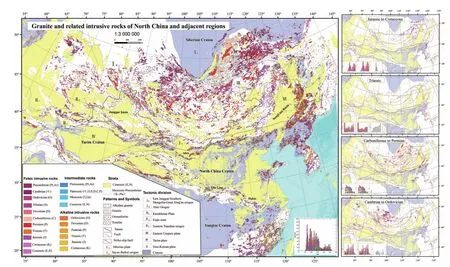

The Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB) is characterized by voluminous granitoids. In the southern CAOB of China, also known as the Northern Orogenic Belt, many new zircon ages have been obtained and provide a basis for reconstructing the spatial-temporal evolution of granitoid magmatism (Fig.1. Wang T et al., 2017a).

In many areas of the southern CAOB, such as the Altai,Junggar, and east-north Tianshan, Early Palaeozoic (500-400 Ma, especially 500-460 Ma) magmatic events have been recognized, resulting in revision of the orogenic evolution. For example, granitoids in the Altai were previously regarded as having formed primarily during Late Paleozoic, and the Altai orogenic belt was interpreted as a Late Paleozoic orogenic belt. However, recent studies show that most granitoids formed during the Early-Middle Paleozoic (470-360 Ma, peak at ca. 400 Ma, Wang T et al., 2006, 2010). These granitoids are mainly of calc-alkaline I-type and formed in a subduction or accretionary tectonic setting. At the southern margin of the Altai orogen, Late Paleozoic (290-270 Ma) I-type and I-A type granitoids were emplaced in a post-accretionary setting(Tong Y et al., 2014). Additionally, many Triassic I- and/or IA type granitoids and some Jurassic granitoids were newly identified, including pegmatites and mafic dikes, indicating that Mesozoic magmatism existed in the northern Xinjiang and Beishan areas, providing new data for Mesozoic geological and metallogenetic settings (Wang T et al., 2014).

Granitoids with 300-270 Ma mainly occur in the western Junggar. However, the new discovery of about 500 Ma granitoids has changed our understanding of the region, previously based on Late Paleozoic granitoids (Chen JF et al., 2010; Han BF et al., 2011). These data reveal an Early Paleozoic accretion event along the southern margin of the CAOB. In the Beishan area, 470-425 Ma granitoid were emplaced in a continental-arc setting, whereas 425-380 Ma granites formed in a collisional and subduction-accretionary setting. Furthermore,290-270 Ma granites were generated in a continental margin or intraplate setting, and 290-270 Ma granites intruded in a post-orogenic setting (Li S et al., 2012, 2013a,b).

A nearly Paleozoic continental-arc has been identified along the northern margin of the Tarim Craton, providing new evidence for the South Tianshan Ocean having been subducted to the south (Qin Q et al., 2016). A large number of Permian granites, mostly A-types, have been identified in the southern Tianshan, with the characteristics of stitching plutons (Han BF et al., 2011). This magmatism shows a westward directed scissors-like closure of the Paleo-Asian Ocean,becoming younger from east to west (Huang H et al., 2015).In the northern Alxa region, granitoids emplacement occurred at 441-321 Ma and 301-248 Ma. The Permian magmatism was dominated by mixed source, and occurred in a subduction setting (Shi XJ et al., 2014; Zhang JJ et al., 2016). The tectonic setting may be also related to a mantle plume as proposed by Dan W et al. (2014).

Voluminous granitoid rocks occur in the northeast China.They were previously considered to have formed in the Proterozoic-Paleozoic, but numerous new U-Pb zircon ages show that most of these rocks were emplaced in Mesozoic(Wu FY et al., 2011; Xu WL et al., 2013). Many of them intruded during the Late Mesozoic (145-110 Ma), and some during the Early Mesozoic (Triassic), such as the granitoids identified in the Erguna area (Tang J et al., 2014). On the other hand, new ages also confirm the existence of Paleozoic granitoids (500-400 Ma), which may be products of subduction-accretion and collision within the Paleo-Asian Ocean (Xu B et al., 2013; Ge WC et al., 2015).

2.2. Granitoids in the China Central Orogenic Belt

The China Central Orogenic Belt (CCOB) is located in central China and composed of the Kunlun, Altyn-Tagh, Qinling, Tongbai and Dabie orogens or mountains. A growing numbers of geochronological data show that granitoids in the CCOB were mainly generated during the Proterozoic, Paleozoic, Early Mesozoic and Late Mesozoic (Fig.1). In the Qinling orogenic belt, Neoproterozoic granitoids were emplaced during three phases, 979-911 Ma, 894-815 Ma, and 759-711 Ma, corresponding to strongly deformed S-type (Granite gneiss), weakly deformed I-type and undeformed A-type granites. These magmatic phases occurred in a syn-collision(979-911 Ma), post-collision (894-815 Ma), and intraplate(759-711 Ma) settings, respectively. They may be a reflection of amalgamation of ancient continental blocks (Wang Q et al.,2005; Wang XX et al., 2013a, 2015a,b). The Neoproterozoic granitoids also occur in the northern Qaidam basin, the Altyn-Tagh and the northern Kunlun of the western CCOB.

Fig. 1. Comparative chart between granitoids in North China, Central-Asia and the China Central Orogenic Belt. ( after Wang XX et al., 2016, spatial-temporal evolution framework of Phanerozoic granitoids in some important mineralization zones, tectonic setting, and metallogenetic meaning, from China Geological Survey).

In the areas of the northern Qaidam basin, Altyn-Tagh,northern Kunlun, Qinling, and Tongbai orogenic belts, ca.500-400 Ma granitoids are also found (Wu CL et al., 2009,Wang T et al., 2009, 2013a). In particular, the ca. 500 Ma S-type granites in the northern Qinling area are consistent with the time of ultra-high-pressure metamorphism (Wang T et al.,2009). Granitoids in the Qinling orogenic belt were emplaced during three phases, at 507-470 Ma, 460-422 Ma, and 415-400 Ma, respectively, accounting for subduction, syn-collisional, and post-collisional settings (Wang T et al., 2009,2013a). The geochronology and geochemical study of granitoids in the northern Qilian and the northern boundary of the Qaidam basin, and a study of the relationship between these and high pressure/ultra-high pressure metamorphism shows that the Paleozoic granitoids at the northern boundary of the Qaidam basin were mainly emplaced during five phases: (1)460-475 Ma, 440-450 Ma, 395-410 Ma, 370-385 Ma, and 260-275 Ma, in response to ocean crust subduction, continental subduction, collision and plate exhumation, respectively(Wu FY et al., 2004). Among these, 450 Ma rapakivi granites at the northern boundary of the Qaidam basin constitute some of the rarest Paleozoic orogenic rapakivi granites in the world(Wang T et al., 2013b). Granite studies in the northern Qilian area show that the North Qilian Ocean was subducted to the south and to north simultaneously during the Early Paleozoic(Wu FY et al., 2011). Granitoids in the south Altyn-Tagh were emplaced during five phases (Wu CL et al., 2016): (1) >460 Ma, A-type granites, formed in a subduction setting; (2)450-435 Ma, high-K calc-alkaline I-type granites, generated in a post-collisional setting; (3) 411-400 Ma, A-type granites,relate to adjustment after collision; (4) 350-343 Ma S-type granites, are related to the Tethys compressive structures; (5)characteristic I-type granites intruded at 265 Ma, possibly related to movement along the Altyn-Tagh fault. Kang L et al.(2016) divided Early Paleozoic granitoids at southern boundary of the Altyn-Tagh into four groups: (1) > 500 Ma,as characteristic of mafic-ultramafic magmatism and O-type adakites, having formed in a subduction setting; (2) 450-470 Ma I-type and S-type granites are characteristic of syn-exhumation magmatism after slab break off; (4) 420-385 Ma,with A-type compositions, having formed during post-collisional extension during. In general, the Altyn-Qilian orogenic belt basically formed during a post-collisional phase in the Late Ordovician, but orogenic magmatism at about 400 Ma still occurred in areas around Dunhuang, indicating a different evolutionary history from the CCOB in the Early Paleozoic and late Paleozoic (Wang N et al., 2017). Early Mesozoic granitoids in the CCOB are widely distributed, and magmatism becomes younger from west to east (Fig. 1). In general,this magmatism can be divided into two phases in the Qinling orogenic belt. The early phase (250-235 Ma) is primarily dominated by I-type granites such as quartz diorites and granodiorites. Granodiorites and monzonitic granites are the main rock types emplaced during the late phase and show characteristic of I-, I-A and A-type granites; where rapakivi granites are also found. The early phase may have been related to subduction, whereas the late phase was generated in a post-collisional setting (Zhang HR et al., 2013a,b; Wang XX et al.,2013a, 2015). Additionally, an increasing number of Triassic(240-210 Ma) granites have been identified in the eastern Kunlun orogen (Ren HD et al., 2016).

Late Mesozoic granites in the CCOB mainly occur in the eastern part, known as the eastern Qinling belt, and include two magma phases: 160-130 Ma and 120-100 Ma, reflecting an evolution trend from I-type via a transitional I-A-type, to an A-type. This is consistent with the magmatic evolution trend in the Yanshanian in eastern China and may belong to the extensive magma belt along the west Pacific margin(Wang XX et al., 2013a, 2015). Ca.160-120 Ma granites were also identified in the western part of the Kunlun Mountains.

2.3. Mesozoic granitoids in southern China and along the southeastern coast of China

For a long time, domestic and foreign researchers have carried out many studies on the granitoids in eastern China,especially Mesozoic granitoids in South China. These Mesozoic granitoids were emplaced during early and late Mesozoic phases, corresponding to the Indosinian and Yanshanian movement

2.3.1. Early Mesozoic (Indosinian) granitoids in South China

Indosinian granitoids in South China consist of different types and have variable ages and origins. They occur in several belts, divided into the Vietnam-Hainan Island, South China inland, Wuyi-Yun Kaishan Mountain, Zhejiang coast-Taiwan,and Sulu-South Korea belts (Mao JR et al., 2011, 2013a,b,c).The Vietnam-Hainan Island granitoids are also divided into early (253-239 Ma) and late (239-211Ma) generations. The early-generation granitoids consists of gneissic garnettourmaline granite, two mica granite, and high potassium calc-alkaline granodiorite-monzogranite-granite. The lategeneration granitoids consist of alumina-rich A-type granite and syenite. Granitoids in the South China inland and Wuyi Mountain belts formed during early (243-233 Ma) and late phases (224-204 Ma). The early phase is characterized by crustal-sourced A-type granites, and the late phase resulted from crust-mantle mixing generating I-type monzogranite and granodiorite (Chen CH et al., 2011; Mao JR et al., 2011,2013a,b,c). Granitoids in the Zhejiang coastal zone are composed of aegirine quartz syenite and alkaline granite (235-215 Ma) (Sun Y et al., 2011; Mao JR et al., 2013a,b,c). The Sulu-South Korea belt includes quartz-syenites (215±5 Ma, Yang JH et al., 2005).

Liu H et al.(2016) divided the Mesozoic magmatic rocks in South China into "two zones and four belts", revealing that magmatic activity in South China had the characteristics of multi-block aggregation and multi-directional compressionextension. The two zones are a Triassic granite area and a middle Jurassic granite area, and the four belts consist of three compression-extensional volcano-intrusive rock belts, and an extensional volcano-intrusive rock belt. They are the Qinzhou-Hangzhou Bay (J2-K1), the middle-lower reaches of the Yangtze River (J3-K1), the southeastern Coast of China, and the Nanling belt. Amongst these, the Triassic granite zone has two age peaks (243-233 Ma and 224-204 Ma). In the Nanling belt there are 200-180 Ma basic-ultrabasic rocks and alkali basalt, high titanium basalt-rhyolite bimodal volcanic rocks,and A-type granites and kohalaite syenite (Li XH et al., 2003;Ye HM et al., 2013), which are products of post-Indosinian activity. Therefore, the Triassic granites zone and the Nanling-belt magmatic rocks belong to the Paleo-Tethys tectonic system.

2.3.2. Late Mesozoic (Yanshanian) granitoids in South China

Zhao XL et al.(2017) divided the Mesozoic intrusive rocks in the eastern part of the Qin-Hang belt into three generations:175-151 Ma adakitic quartz diorite- granodiorite, 150-136 Ma I-S type granites, and 133-123 Ma A2-type granites. The ages of a quartz diorite porphyry and a granodiorite-porphyry of the Chuankeang-Tongshan plutons in northeastern Jiangxi Province are 175-172 Ma (Zhao XL et al., 2017), and the A2-type granite has an age of 133-124 Ma (Li ZL et al., 2013),showing characteristics of "scissor-type" migration to the ocean.

In the middle Jurassic granite area, about half of all granites occur in South China. The rock types are mainly crustalsourced S-type monzogranite and biotite granite, accompanied by K-feldspar granite, two-mica granite, and granodiorite,whose ages range between 170 Ma and 155 Ma (Mao JR et al., 2013a,b,c).

The ages of Cretaceous volcano-intrusive rocks on the southeastern coast of China are concentrated in two generations: 145-12 Ma and 120-85 Ma (Mao JR et al., 2013a,b,c).Li JH et al.(2014) ascribed these rocks to two tectonic-thermal events at 145 Ma and 136-86 Ma, respectively, and two extension events occurred after 145-137 Ma compression, at 136-118 Ma and 107-86 Ma, respectively.

The volcano-intrusive rocks (not including the Ningzhen Mountains) in the middle -lower reaches of the Yangze River(J3-K1) are divided into three generations (Zhou TF et al.,2012): (1) 145-136 Ma high-K calc-alkaline dacite-rhyolite volcanic-intrusive rocks, adakite-like rocks, and copper-iron deposits; (2) 135-127 Ma trachyandesites and trachytes of the kohalaite series, and copper-gold deposits; (3) 126-123 Ma phonolites of the alkaline series, syenites, A -type granites and iron deposits. Wang T et al. (2014) divided the mineralization into four generations: 145-140, 142-135, 135-125 and 110-100 Ma. The youngest generation consists of adakite that is closely related to copper-iron deposits in the Ningzhen area,emphasizing a 15 Ma time interval between its emplacement and bimodal volcanic rocks and A-type granites of the Ningwu area. Liu H et al. (2016) investigated Yanshanian igneous rocks in these areas, such as the eastern part of the Qin-Hang belt, the middle Jurassic granite zone, and the southeastern coast of China that belong to the Paleo-Pacific tectonic system. It is implied that granitoids in the middle-lower reaches of the Yangtze River may be the result of complexities caused by interaction between the Paleo-Asian and Paleo-Pacific tectonic systems.

Zhai MG et al.(2016) compared Mesozoic magmatic rocks from the North China Craton (NCC), the Korean Peninsula(KP) and Japan (JP). The results show that (1) Triassic granite chronology, petrology and geochemistry in the NCC, KP and JP are similar, which may reflect similar settings; (2) Jurassic granites with ages of 175-157 and 157-135 Ma occur in the NCC, whereas granitoids in the KP are mainly 190-170 Ma in age, and 160-135 Ma granites are rare in both the KP and JP; (3) the subduction system of the Paleo-Pacific plate is about 130-120 Ma in age, whereas 90-60 Ma granitoids are mainly developed in the southwestern KP, and all over JP.

2.4. Granitoids in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau

The Qinghai-Tibetan plateau granitoids have attracted global attention. Research progress on granitoids in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau includes the following: (1) many new isotopic age data have been reported; (2) a new geochronology framework has been established, and (3) a tectonic and granitoid map of the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau and adjacent area has been completed (Mo XX et al., 2013). Granitoids in the Songpan-Ganzi area in the central-northern part of the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau mainly intruded during 228-204 Ma, and consist of various types such as high-K alkali granite, adakitic rocks, A-type granite and I-type granite (Zhang HF et al.,2007a,b; Yuan C et al., 2010; Chen Q et al., 2017). The association of A-type and adakitic granitoids suggests an extension environment of formation. However, several different geodynamic models were proposed for their formation, including back-arc, slab rollback (Ding L et al., 2013; Sigoyer et al., 2014; Zhang LY et al., 2014), slab break-off (Chen Q et al., 2017), and lithosphere delamination (Zhang HF et al.,2007a,b; Yuan C et al., 2010).

Emplacement of granitoids in the northern Qiangtang area is mainly occurred during three main phases: Late Permian to Early and Middle Triassic, Late Triassic and Cenozoic. The Late Permian-Early Triassic granitoids include the Tuotuohe quartz syenite porphyry (254 Ma, Zhang HR et al., 2010) and the Jitang granitic gneiss (249-237 Ma, Hu PY et al., 2014).They are related to subduction and closure of the Longmucuo-Shuanghu part of the Paleo-Tethyan Ocean (Yang TN et al.,2011; Zhang HR et al., 2013a,b). Late Triassic granitoids formed during 228-200 Ma and resulted from southward subduction of the Ganzi-Litang part of the Paleo-Tethyan Ocean(Yang TN et al., 2012; Zhang HR et al., 2013; Zhang HR et al., 2017). Paleocene adakitic granites have recently been found in the northern Qiangtang area, suggesting that there was thickened crust in this region at the beginning of the Cenozoic (Zhang JJ et al., 2015).

There is an E-W trending Late Triassic granite belt (224-202 Ma) in the middle section of the Qiangtang area. These rocks along the Longmucuo-Shuanghu suture zone formed by partial melting of continental crust during collision (Peng TP et al., 2015; Liu H et al., 2016; Tao Y et al., 2014; Li GM et al., 2015; Lu L et al., 2017). A set of granitic gneisses with ages of 488-467 Ma intruded into the southern Qiangtang area(e.g. Zhao ZB et al., 2014). These magmatic rocks can also be found in the Baoshan area to the south (Liu S et al., 2009),providing important evidence to constrain the early Paleozoic evolution in this area.

Voluminous Cretaceous to Cenozoic granitoids were reported from the Lhasa Block (Chung SL et al., 2005; Mo XX et al., 2005; Chiu et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2009) and record the evolution of the Neo-Tethyan Ocean and subsequent continental collision. Numerous granitoids with older ages have been reported recently such as Jurassic (Chiu HY et al., 2009;Ji WQ et al., 2009; Chu MF et al., 2006; Zhu DC et al., 2008),Triassic (Zhang HF et al., 2007a,b; Ji WQ et al., 2009), Permian (Zhu DC et al., 2009, 2010), and even Neoproterozoic(787-748 Ma, Hu DG et al., 2005). These data provide new perspective and form a basis for understanding the tectonic evolution of the Lhasa Block.

Granitoids in the Himalaya area are mainly composed of Neoproterozoic to early Paleozoic granitic gneiss (553-459 Ma) and Cenozoic leucogranite (44-2 Ma). The former was interpreted to reflect Pan-African events in the Himalayan region ( Booth et al., 2004; Singh and Kumar, 2005). The latter is considered to be the product of partial melting of crustal rocks ( Zeng LS et al., 2009), with fluid-absent and fluidfluxed melting of muscovite (Zeng LS and Gao LE, 2017;Gao LE et al., 2017). Recent studies provide new interpretations and petrogenetic models ( Zeng LS et al., 2009; Wu FY et al., 2015; Gao L et al., 2017), emplacement mechanisms(Zhang JJ et al., 2012) and tectonic models (Liu ZC et al.,2017) for these Cenozoic leucogranites.

3. Construction of granitoid plutons and granitoid structure

3.1. Construction of granitoid pluton

The granitoids problem is ultimately a geological problem. To study granitoids, we should first consider it as a geological body and then carry out detailed geological mapping.In the early 1:200000 geological mapping, the granitoid pluton (or batholith) is divided by the rock facies, which is considered as the product of cooling crystallization. But then the mapping and research (e.g. a unit and super-unit method in the 90 s) have revealed that different lithologies of a granite pluton (component difference or structure difference) are the different intrusive episodes or the product of magma mixing.

Therefore, in nature, most plutons are granitic complex,which has characteristics of multiple magma aggregation and episodic growth. The formation and growth a pluton can be summarized as central, eccentric, lateral, irregular patterns.The former can be regarded as non-polar or unidirectional growth (no migration of emplacement centers), and the latter four belong to polar or directional growth that may provide structural kinematics information (Wang T et al., 1999). For example, the largest Paleozoic Huichizi granitoid pluton in the central Qinling has set up three super units (series) and nine units, revealing a growth process of the eastward migration of the emplacement center (Wang Q et al., 2005).

In addition, detailed mapping and precise dating can be used to describe the formation and construction process of a pluton and its time scale. Some complex plutons can be formed in several million years (Glazner AF et al., 2004).Whether the analytical level can accurately determine the time scale of an instantaneous massive granite batholith (e.g., one Ma or several Ma), which requires continuous exploration. It has been shown that the instantaneous formation of a massive granite batholith (magma flare-up) should have been a reflection of a structural or tectonic movement. For example, the magmatic emplacement within 52-51 Ma in the collisional magma zone of the Qinghai-Tibet plateau is likely to be the response of (about 53 Ma) Neo-Tethys ocean break-off (Zhu DC et al., 2013). Some of the large granite belts may have been built at a slower rate, some of which might have gone through hundreds of millions of years (Myr).

On the basis of all this information, the formation process and spatial-temporal migration of the giant granite belt is also revealed, to analyze the regional dynamics. For example, the NW migration of Mesozoic magmatic belt in South China and later SE migration may be related to slab subduction (Li ZX and Li XH, 2007) and slab retreat (Zhou XM et al., 2006).The Gangdise magma belt (80–40 Ma) in the Qinghai-Tibet plateau migrated first from south to north and then from north to south, revealing subduction and slab retreat dynamics (Mo XX, 2011; Zhu DC et al., 2013). The orogen-parallel migration of the magma emplacement is believed to be the result of the ocean scissor-like closure and subduction-collisional orogeny (Huang H et al., 2015). The Early Cretaceous extension of the Gangdise continental arc in the southern part of Tibet,may be the result of trench retreating and strong corner flow of mantle in the front of arc, during the northward subduction of the Neo-Tethys ocean (Zeng LS and Gao LE, 2017)

3.2. Emplacement mechanism and deformation of granitoid plutons

Emplacement mechanism of granitoid plutons and their space problem have always been a difficulty questions to be answered. Chinese researchers have also explored this aspect.For example, some researchers have studied the diapirism emplacement mechanism on the Fangshan pluton (He B et al.,2009). The forceful emplacement of granitoid plutons can also occur in the extension environment, e.g., plutons that are emplaced during the formation of a metamorphic core complex(Wang T et al., 2002). In fact, in most cases, the emplacement mechanism of a pluton is complex, such as the threemember complex emplacement mechanism (Wang T et al.,2000), which also helps understand the problem of emplacement space.

In addition, some researchers also discussed emplacement mechanism of regional granite plutons. For example, Feng Zuohai studied the regional structure characteristics of the South China granitoids and their emplacement mechanisms,revealing the Jurassic Guposhan-Huashan incremental growth mechanism (Feng Z et al., 2012). Liu Hongsheng studied the emplacement mechanism of the Jurassic granite in South China. In addition, the application of magnetic fabric measurement to explore the emplacement mechanism was also carried out ( Liu HS, 2017).

The granitic pluton is one of the best structural markers,and its shape and deformation degree can be used as the regional kinematic indicator. Many plutons with unsymmetrical pattern may reflect local or regional shear structure kinematics and dynamics. For example, the σ-shaped Shangnan pluton in the north Qinling indicates the sinistral shearing along the Shangdan suture (Wang T et al., 2005).

The accurate dating of structural deformation has been a difficult problem in structural geology, especially for multistage deformations and high temperature deformation.According to the relationship between plutons and regional structure, we can determine pre-tectonic pluton, syn-tectonic pluton and the post-tectonic pluton. Based on the zircon dat-ing of these plutons, the formation age (not the deformation age) can be determined, and then the deformation ages can be constrained. So, the determination of the relationship between the large-scale pluton and the tectonics, and the precise dating can be used to more accurately determine the deformation time. For example, by the cutting relationship of strong deformation, weak deformation, and non-deformation granitoid plutons and zircon dating of these plutons, the ductile deformation time of themylonites in the metamorphic core complex in the NE Asia werebe determined, that is, the early extension(150-145 Ma), peak extension (145-130 Ma), late extension(130-120 Ma) (Wang T et al., 2012).

4. Types of granitoids, metallogenesis and tectonic environment

Chinese granitoid is not only widely distributed, but also includes various types, some of which have distinct characteristics and special meanings.

4.1. Alkali Granite

As a special type of granite, typical alkaline dark minerals,such as aegirine, aegirine-augite, arfvedsonite and sodium amphibole are characterized as alkaline granite. Alkaline granites are well developed in the China and distributed along the fault zones, forming more than dozen alkaline granite belts(Zhao ZH et al., 2003). Early studies focused on rock assemblages, mineral composition, geochemistry and isotope characteristics (Zhao ZH and Zhou LD et al., 1994; Hong DW et al., 1994). In recent two decades, the high precision U-Pb zircondating has significantly improved the geochronology research of alkaline granites. In some key areas, new identifying alkaline granites are helpful to determine the spatial and temporal distribution of the alkaline rock belts and their petrogenesis and background.

4.1.1. Spatial-temporal distribution of the alkaline granites in China

A large number of Permian (299-260 Ma) alkaline granites were identified in the southern margin of the Central Asian Orogenic belt and the northern margin of the North China -Tarim cratons, forming two giant Permian alkaline granite belts (Altai - East Junggar - south Mongolia - north Inner Mongolia - north of Heilongjiang province, the southern margin of Tianshan -Tarim -Alax-northern margin of North China craton), providing key evidence for determining the evolution of Paleo-Asian Ocean and the relationship with Mongolian-Okhotsk Ocean. In addition, early Mesozoic alkaline granite belts were developed in the north margin of North China craton (Yan GX et al., 2000; Yang TN et al., 2012). Recently,early Devonian alkaline rocks also have been identified in this belt (Wang T et al., 2012).

In the China Central Orogenic Belt, volume pre-Mesozoic alkaline granites were identified. Such as, several Paleozoic(420-400 Ma) alkaline granites (Xu T et al., 2017) were determined in the western Qinling- north Qilian, and new Proterozoic (686-650 Ma) alkaline granites were determined in the south Qinling-Dabie-Sulu (the margin of Yangtze Craton) (Zhang JJ et al., 2012; Wang T et al., 2017a,b),providing evidences for discussing the early evolution of Qinling orogenic belt and north Yangtze.

In the central of South China, several Cretaceous alkaline granites (137-86 Ma, Wang Q et al., 2005) were identified and formed two parallel northeast late Mesozoic alkaline granite belts in South China (Xu XS, 2008).

4.1.2. Petrogenesis and setting

Alkaline granites have different genetic types, and alkaline granite in China also have different petrogenesis in different regions. The alkaline granites on the north of the North China-Tarim cratons are believed to be related to mantle-driving source, such as young accretion or metasomatic mantle(Niu XL et al., 2016). But most alkaline granites in South China and North China carton are considered as the magma mixing of crust and mantle (Wang T et al., 2015).

Most of the alkaline granites in China are formed in a post-orogenic extension setting, such as the giant Permian alkaline granite belt in the southern margin of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt (Hong DW et al., 2004; Han BF et al., 2011;Tong Y et al., 2015). Many alkaline granites are formed in the intraplate rift environment, such as the Triassic alkaline granites in the north margin of Tarim-North China cratons (Yang TN et al., 2012), and a large number of late Mesozoic rift alkaline granites of northeast China, North China, especially the area of Taihang (Wu FY et al., 2011; Yang TN et al., 2012). Whereas, others believe that some alkaline granites formed with subduction, such as Neoproterozoic alkaline granites in the west margin of Yangtze Craton (Zhao XF et al., 2008) and Cretaceous alkaline granites in South China (Wang T et al., 2005).

Alkaline granite magmatism is closely related to mineralization, especially with Au-Cu and W-Sn deposits (Zhao ZH et al., 2002). The W-Sn deposits related to alkaline granite mostly distribute in South China and Qinghai-Tibet plateau.The rare earth deposits with alkaline granite were also well distributed in these areas, and often associated with highlyfractionated granite

4.2. Highly fractionated granites

Highly fractionated or highly evolved granites generally include less dark minerals with low color rate. They are mostly located in the center of pluton, and most of them are coeval with granite aplite and pegmatite (Wu FY et al., 2017).The composition of materials is dominated by quartz, K-feldspar and albite (or plagioclase), whose typical characteristics are amazonite, tourmalinite, lepidolite, and lithium muscovite,with a tetradeffect. Highly fractionated or highly evolved granitoids have very little outcrops in Xinjiang, China, such as No.3 pegmatite dyke of Altay, Xinjiang (Yin R et al., 2013).They are mainly distributed in northeast China, South China,and the Himalaya. The highly fractionated granites in northeast China is mainly formed in the late Mesozoic (Jahn BM et al., 2001; Wu CL et al., 2004; Wu FY et al.,2017), accompanied with amounts of alkaline (A-type) granites, alkaline rocks(Jahn BM et al., 2001; Wu FY et al., 2011). The highly fractionated granites in South China are mostly developed with dozens of plutons (Zhao ZH et al., 2002; Chen B et al., 2014),which is the greatest feature of widespreadMesozoic granites in South China (Li XH et al., 2007). Many leucogranites in the Himalaya Mountains are also highly fractionated granites( Wu FY et al., 2015; Wang T et al., 2017a.b; Zeng LS and Gao LE, 2017). Synchronous A-type granites or alkaline granites are not found, showing the differences with the above two formers, representing a different genetic mechanism with them (Wu FY et al., 2017).

The highly fractionated granitoids have obvious unique mineral composition, whose associated minerals mainly include W, Sn, Nb, Ta, Li, Be, Rb, Cs and REE etc., such as the Nb-Ta, W-Sn, W-Mo deposits of South China, the Te-Pb-Zn-Au deposits and the Fe-Cu deposits of the Himalaya. Leucogranites should be the main targets when searching for these similar metal deposits in future.

The origin of highly fractionated granitoids is controversial. In recent years, some domestic and overseas researchers suggested that there is nothighly fractionated granite in the world (Glazner AF et al., 2004). The main reason is that the granite magma is high SiO2, high viscosity, and contains many crystallized minerals and similar density, making the crystallization different. Moreover, the conclusive evidence of crystals deposit has not yet been found in the field. But, the field observation, the mineral composition and change of composition in the micro scale by microscope, and geochemical data show that granite magma can be differentiated(Breiter K et al., 2013; Wu FY et al., 2017). The differentiation caused by the flow may be the main reason for the variation of the magmatic composition of the granites. This is definitely noteworthy.

4.3. Leucogranite

There are two world-renowned leucogranite belts developing in the Himalayan region of the southern Tibetan Plateau.The south belt, which is known as High Himalayan leucogranite belt, is mainly distributed along the South Tibetan detachment system (STDS), and the north belt is located in the Tethys Himalaya which is known as the Tethys Himalayan leucogranite belt. Leucogranite consists of quartz, K-feldspar,plagioclase, biotite (<5%), muscovite, tourmaline, and garnet in different proportion; moreover, it can be classified into three major rock-types including two-mica granite, luxulianite, and garnet-granite. Traditionally, Himalayan leucogranite was considered as purely low crustal melting granite. Recently, Wu FY et al.(2015) pointed out that this kind of granite probably evolved from high-temperature granitic magma and is likely to be highly-fractionated granite, which can be divided into three stages, Proto-Himalayan (44-26 Ma), Neo-Himalayan (26-13 Ma) and Post-Himalayan (13-7 Ma). The first stage corresponds to the continent-continent collision orogeny, which was caused by the convergence of Indian Plate and Asian Plate; the other two stages correspond to the uplift of Tibetan Plateau and related to the delamination of thickened Himalayan - Tibetan Plateau collisional orogenic belt. However, Zeng LS and Gao LE(2017) considered that leucogranite in Himalayan orogenic belt is probably a product of the partial melting of pelite including two types of partial melting: water-fluxed partial melting of muscovite (Type-A)and partial melting of muscovite dehydration (Type-B). Recent studies indicate that Himalayan leucogranite has a great metallogenic potential for rare metals and it can possibly become an important rare metallogenic belt in China. Furthermore, the investigation and research should be strengthened on rare metal mineralization in this region, in order to provide a theoretical basis for rare metal mineral resources in China(Wang T et al., 2017a,b).

4.4. Adakitic granitoids

The study of adakites and adakitic rocks can be considered to be thriving in China. However, there are still debatable understandings regarding adakite, adakitic rocks and their significance. Chinese geologists proposed that a genetic model of partial melting of delaminated lower crust and lithospheric delamination (Xu JF et al., 2014) and magma mixing(Chen B et al., 2013). Zhang HR et al. (2015) discussed some experimental studies of adakite and considered that the most important truth about adakitic is garnet existing in the source region while plagioclase not existing. The most important feature is high pressure. Wang Q et al. (2006) addressed the genetic relationship between ore deposit of porphyry Cu-Mo-Au and adakite or adakitic rocks. In addition, it is emphasized that adakite and adakitic rocks can be considered as metallogenic parent rock of porphyry Cu-Mo-Au deposit. Chung SL et al. (2003) revealed that there exists a E-W Miocene (10-26 Ma) adakitic rock belt in Gangdise area, and it has also been pointed out that this belt is a product of lower crust melting.

Due to the development of the concept of adakite since it was proposed, new ideas were expanded regarding the exploring depth (pressure) of magma and evaluating the relationship between granite composition and crustal thickness. According to this, further granite classification attempt by pressure was proposed (Zhang HR et al., 2015), which can be considered as a definitely worth studying. It is necessary to pay attention to the petrogenesis of adakitic rock is various, for example, magma mixing (Chen B et al., 2013). Therefore, in order to explore magma original depth and evaluate crustal thickness, the first thing to do is to eliminate other possible petrogenesis and find out the particular adakitic rock, which is related to pressure and crustal thickness (Profeta L et al., 2015).

4.5. Rapakivi granite

Rapakivi granites are special type of granites, characterized by Proterozoic age, rapakivi texture, anorogenic setting and A-type granites, and they mainly occur in the cratons of the Northern Hemisphere. This kind of typical Proterozoic rapakivi granites also occur in the North China Craton (Yu JH et al., 1996), and many studies have been done on them(Rämö TO et al., 1995;Yang JH et al., 2005; Zhang HF et al.,2007a,b). Recent studies have revealed emplacement sequence of the different rock types in the rapakivi pluton, and the processes of magmatic evolution and crystallization conditions (Wang T et al., 2017a,b).

More and more studies show that similar rapakivi granites can also occur in the Phanerozoic orogenic belts. Significantly the Proterozoic, Paleozoic and Mesozoic rapakivi granites were identified in the China Central Orogenic System(CCOS), it is first time to recognize three-stage rapakivi granites in one orogenic belt. Here are major processes on the study of those granites (Lu XX et al., 1996, 1998; Xiao QH et al., 2003; Wang XX et al., 2008, 2013a, b, 2015a,b).

The Proterozoic rapakivi granites (1797-1763 Ma), occur in the Paleozoic North Qaidam orogen, western segment of the CCOS (Xiao QH, 2003; Wang T et al., 2015), and they are approximately 60 Ma older than other the Proterozoic rapakivi granites (1715-1682 Ma) found in North China Craton. However, their ages are consistent with those of most rapakivi granites in the Northern Hemisphere (such as Mazur(about 1750 Ma) and Korosten rapakivi (1790-1760 Ma) in the southeast of Eastern Europe). Moreover, those rapakivi granites are similar with those in the Northern Hemisphere in geochemistry and tectonic setting.Therefore, they also are a member of the giant rapakivi granite belt in the Northern Hemisphere, and later was involved in the Paleozoic orogenic belt (Wang T et al., 2015). It is notable that the isotopic composition of those rapakivi granites are similar to that of rapakivi granites in the North China Craton, which suggests they both have similar sources and implying part of the basement of the western CCOS similar to that of the NCC. This provides new data to solve the dispute on the basement origin in the western segment of the CCOS, The Palaeozoic rapakivi granites (about 433 Ma) also occur in the Paleozoic North Qaidam orogen, western segment of the CCOS. They are the first Paleozoic rapakivi granites found in an orogenic belt in China and emplaced in a post-collisional setting. Magmatic enclaves often found in the rapakivi granites. The rapakivi granites and enclaves have the similar age and Nd isotopic composition but different Hf isotopic compositions, showing magma mixing (Wang XX et al., 2013a).

The Mesozoic rapakivi granites (210-220 Ma) are located in Qinling and Kunlun orogenic belts (Lu XX et al., 1996,1998). The granites have rapakivi texture similar to the typical rapakivi texture, but their geochemical characteristics slightly differ from the typical one; therefore, these rapakivi granites can be called rapakivi-texture granites or orogenic rapakivi granites (Wang XX et al., 2003).

Mesozoic rapakivi granite (210-220 Ma) is developing in Qingling and Kunlun orogenic belts (Lu et al., 1996; 1998).This rapakivi develops the same or similar rapakivi texture with typical rapakivi, but the geochemical characteristics slightly differ; therefore, this rapakivi can be called rapakivitexture granite or orogenic rapakivi (Wang XX et al., 2003).

Origin of rapakivi texture is still an unsolved problem in petrology. Generally, the formation of this texture is related to the change of temperature, pressure or composition during magmatic crystallization (Haapala and Rämö OT, 1999). The origin of rapakivi texture of the Phanerozoic rapakivi granites in the CCOS is considered as the result of abnormal rise of magma temperature and composition change caused by basic magma injected into acidic magma which leads to the melt of alkali feldspar phenocryst and plagioclase crystallized on periphery (Wang XX et al., 2008)

4.6. Relationship between granitic genetic type and metallogenesis

The relationship between granitic magmatism and metallogenetic process has been synthetically and deeply studied by Chinese researchers. A large-scale metal metallogenesis associated with Mesozoic magmatism, particularly Yanshanian magmatism, occurred in eastern China, which is the most significant Mesozoic metallogenetic event in the world and istermed as “Mesozoic Metallogenic Explosion” (Hua RM and Mao JW, 1999; Pei RF et al., 2008). Mao JW et al. (2008)compiled the spatial-temporal distribution and types of major ore deposits forming in the Mesozoic metallogenic events in South China and pointed out the relationship between these events with granite magmatic events. The late Triassic minerogenetic series is W-Sn-Nb-Ta (tungsten-tin-niobium-tantalum); the middle-late Jurassic minerogenetic series can be further divided into 170-160 Ma porphyry-skarn-type Cu deposits and 160-150 Ma W-Sn polymetallic deposits associated with coeval granites; the main peak period of Cretaceous metallogenesis is 100-90 Ma, and main minerogenetic series are epithermal silver-gold deposit and W-Sn-Cu polymetallic deposit associated with granite. Chen J et al. (2008) summarized the features of late Jurassic granite mineralization in Nanling area, and classified the W-Sn-Nb-Ta-bearing granites into three main types: W-bearing granite (containing tungsten), W-Sn-bearing granite, and Nb-Ta-bearing granite;moreover, it was suggested that each type has distinct evolutional characteristics and the mineralization was closely related to the evolutionary history. The petrogenetic and metallogenetic features of intracontinental porphyry deposits in the Middle-Lower Yangtze River Mineralization Belt were summarized by Zhou TF et al.(2016) and it was pointed out that this belt was formed during the Yanshanian intracontinental orogenesis. Porphyry magmatism and related mineralization happened predominately during the period of 149-105 Ma. In particular, porphyry-skarn mineralization mainly occurred in the early stage (149-135 Ma) and the late stage (123-105 Ma),and typical porphyry mineralization occurred in the middle stage (133-125 Ma).

The Indosinian granitoids, including adakite, calc-alkaline granite, high potassium-calc-alkaline granite, alkaline rock, rapakivi have a widespread occurrence in Qinling. The most economically important Indosinian ore deposits recently found include carbonate dykes-type, orogenic-type and por-phyry-type molybdenum deposits, Carlin-type or Carlin-like,orogenic-type and porphyry-/breccia pipe-type gold deposits,and orogenic-type silver-dominant polymetallic deposits, suggesting a great prospecting potential of Indosinian ore deposits (Chen CH et al., 2010).

Extensive Cenozoic magmatism-mineralization occurred in the Sanjiang-Tethys Orogen. Hou ZQ et al.(2011) reviewed the petrogenetic and metallogenic characteristics of a number of significant porphyry Cu-(Mo)-(Au) deposits in the eastern Tethyan metallogenic domain. They widely occur in a variety of non-arc settings, varying from post (late)-collisional transpressional and extensional environments to intracontinental extensional environments related to orogenic and an orogenic processes. It was proposed that key factors that generate hydrous fertile magmas are most likely crust/mantle interaction processes at the base of thickened lower-crust in non-arc settings, and that breakdown of amphibole in thickened lower crust (e.g., amphibole eclogite and garnet amphibolite) during melting is considered to release fluids into the fertile magmas, leading to an elevated oxidation state and higher H2O content necessary for development of porphyry Cu-Mo-Au systems. Himalayan leucogranites were the product of crustal anatexis. The petrogenesis, mineral assemblies and mineralization of the Himalayan leucogranites were systematically studied by Wu FY et al.(2015), Wang T et al.(2017a,b) and Zeng LS and Gao LE(2017) , and it was suggested that the Himalayan leucogranites is commonly related to the rare-metal (Nb-Ta-Be-Sn) mineralization and have a great prospecting potential.

The understandings of differentiation process, the interaction between melt, fluid and minerals during late magmatic stages and their roles in enrichment and mineralization of oreforming elements in representative ore-forming granites have been further strengthened. For example, according to the study of Yang TN et al. (2011) and Yang WB et al.(2014) regarding melt inclusions and zircons in Baerzhe Zr-REE-Nbbearing alkaline Granite, the magmatic-hydrothermal process and its significance for rare metal mineralization were described in detail. Li GM et al.(2015) carried out in situ EPMA and LA-ICP-MS analyses on micas in the Yashan W-Nb-Tabearing granitic pluton, in the Yichun area, South China. The results suggested that the enrichment and mineralization of Ta-Nb occurred in the late magmatic stage, while the mineralization of W was related to the interaction of hydrothermal fluids with previously existing micas. Ling HF (2011) reported their new understanding on the sources of uranium and origin of hydrothermal fluids of granite-type uranium deposits in South China. They proposed that the existence of hydrothermal fluids with high oxygen fugacity, which was ultimately originated from meteoric water and could leach uranium from U-rich granites, is the key factor of the formation of granite-type hydrothermal uranium deposits. In terms of such deposits in South China, Indosinian U-rich peraluminous leucogranites were the main source of uranium, and late Yanshanian tectonic extension as well as dyke magmatism provided the heat and the fissure system in these granites, resulting in infiltrating, cycling and leaching uranium from the granites of meteoric water.

5. Tracing granitoid source, deep crust architecture and crustal Growth

5.1. Methods for tracing Source

In recent years, more and more isotopic studies have been applied to determine the granite source. In the past twenty years, several chemical separation procedures for whole rock Hf and zircon Hf isotopes, and laser-ablation zircon Hf analysis procedures have been developed in some domestic laboratories (Wu FY et al., 2007) summarized the principle and application of Hf isotope, which significantly promoted Hf isotope studies of granite. Due to the advantages of Hf isotope analysis, including simple analysis procedure, convenient analysis, low cost, and easy acquisition of in-situ information,zircon Hf isotope study has gradually become a common method in granite study, and plays an important role on granite source research. In-situ zircon O isotope is a recently new analytical method, which plays a significant role in analyzing and discussing the contribution of surface materials (waterrock reaction under low temperature/high temperature).

According to the Nd isotope studies on the Phanerozoic granite in northern Xinjiang, all the granites in this area,which formed in different periods, are characterized by juvenile sources. This indicates that this area is one of the most significant Phanerozoic crust growth area on earth, which is different from the general Phanerozoic crustal origin for granite with negative εNd(t) values in the world. The granite in the northern Xinjiang generally has a positive εNd(t) value similar to the depleted mantle, which is not restricted by time, tectonic setting, and genetic type. Therefore, it proposed that significant continental crust growth occurred in Central Asia Orogenic Belt during the Phanerozoic. The continental crust growth is different from the lateral growth near the subduction zone which is related to the subduction process, and it is probably achieved by magmatism. In addition, this process is an important mechanism of continental crust growth in some area (Jahn BM et al., 2000a, b; Wu FY et al., 2000; Hong DW et al., 2004; Han BF et al., 1997, 2006, 2012; Chen B and Jahn BM, 2004).

In a recent summary of isotopic data of the Phanerozoic granites in the middle-east of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt, Wang T et al. (2017a,b) classified the sources of granite in Central Asian Orogenic Belt into four types: (1) juvenile crust source, characterized by young Nd-mode age (0.8-0.2 Ga), positive εNd(t) value (0 to +8), and positive εHf(t) value,mainly distributed in the Altai (Wang T et al., 2009), the eastern and western Junggar region, the southern Great Khingan and adjacent area (Yang QD et al., 2017); (2) slightly-mixed source, characterized by slightly old Nd-mode age (1.0-0.8 Ga), εNd(t) value around 0, and slightly old Hf-mode age (1.0-0.6 Ga); (3) mixed source, where obvious features of mixed source area and isotopes are shown, characterized by older Nd-mode age (1.6-1.0 Ga), lower εNd(t) value (-10 to 0), older Hf-mode age (2.0-1.2 Ga), and a εHf(t) value (-15 to +7) that varies widely. The granite in the Altai region can be consid-ered as a typical example; (4) ancient source, characterized by very old Nd-mode age (2.8-1.6 Ga), very low εNd(t) value (-23 to -6), very old Hf-mode age (3.0-1.6 Ga), and a εHf(t) value (-20 to -5). These granites are mainly exposed to some Precambrian micro-continental-segments or old terrains, which are formed by recycling crustal materials (Wang T et al., 2017a).

5.2. Deep crustal composition and growth

The issue regarding the deep crustal composition and growth of continental crust is one of the most fundamental and significant scientific problems in geoscience. Central Asia is the most prominent region of Phanerozoic continental crust growth in the world (Jahn BM et al., 2000a, b). Chinese researchers have conducted a large number of valuable researches (Han BF et al., 1997, 2006, 2012; Wu FY et al.,2000; Hong DW et al., 2004; Chen B and Jahn BM,2004;Xiao QH et al., 2009; Wang Q et al., 2006; Sun M et al.,2009).

How to evaluate the amount of crust growth is controversial (Kröner A et al., 2014, 2017). Regional isotopic mapping can be considered as a method to address this issue. For example, in the Altai region, according to the Nd isotope mappingof granite, the amount and method of crust growth can be clearly revealed by estimating the distribution, composition and architecture features of deep old and juvenile crust (Wang T et al., 2009). In the Great Xing’an, four isotopic provinces of Nd depleted mantle model ages can be determined by the granite isotope mapping, and the estimated juvenile continental crust accounts for approximately 65% (Fig. 2; Yang QD et al., 2017).

Xiao QH et al. (2009) discussed the relationship between granitoids and continental crust growth by using the granitoids of the Altai, East Kunlun, North China Yanshan, northeast China and Nanling Mountains as examples, and proposed five types of continental crust growth in China (the Altai, East Kunlun, northeast China, Yanshan, and Nanling Types), which forms a basic way for the Phanerozoic continental crust growth in China.

Regional isotopic mapping can also reveal the spatial and temporal distribution of different mineral resources. For instance, three different isotope zones were indicated by Nd-Hf isotopic mapping of granites in East Qinling, which can limit the distribution of molybdenum polymetallic minerals (Fig. 4;Wang YF et al., 2014).

According to the zircon Hf isotopic mapping of the Gangdise granitiods, Hou ZQ et al. (2015) figured out that the distribution of Cu-Zn deposits is controlled by juvenile crust,whereas the distribution of Pb-Zn deposits are limited by old crust. Some Australian scholars are trying to figure out the restriction of the deep material composition on mineralization by using isotope mapping of metallogenic belt. The results provide a typical example of the study on mineralization and deep process of orogenic belt.

In addition, in order to provide new ideas and research examples for the detection of deep crustal materials, revealing the major differences of the deep crustal composition between the key areas of the Northern and China Central Orogenic Belts and proposing a new marker for identifying the types of orogenic belts such as accretionand collision and the division of development and evolution are both necessary, which can be accomplished by isotope mapping.

A new feasible approach is to explore the material composition of the deep crust by statistical analysis of the information recorded by the captured/inherited zircon (Captured Zircon Mapping) in granite and related intrusive rocks (Fig. 3;Zhang JJ et al., 2015). More studies indicated that captured/inherited zircon can provide important information on magma events “hiding” in the deep continental crust and material composition.Such information can expand the understandings of deep crust, which is beneficial to understanding the composition of deep material, dividing tectonic units and exploring continental crust evolution. For example, the mapping work of captured zircon was carried out in the northern margin of Alxa Block, and it was found that the tectonic boundary between the Alxa block and the Central Asian Orogenic Belt is the Chaganchulu Ophiolite belt instead of the Engewusu Ophiolite belt, which was traditionally believed(Zhang JJ et al., 2015).

Fig. 2. An isotopic mapping of granitoids in the eastern part of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt, revealing basement composition ( after Yang QD et al., 2017).

Fig. 3. Cartoon showing the distribution of the oldest age (207Pb/206Pb > 1000 Ma and 206Pb/238U < 1000 Ma) for xenocrystic/inherited zircons within igneous rocks from the Alxa and its nearby regions (a); and Section across Hf crustal model age maps for xenocrystic/inherited zircons and igneous rocks of the southern CAOB and the ZS and YNH zones (b). This carton indicates that the boundary between the Central Asian Orogenic Belt (CAOB) and the northwestern margin of Alxa block should be near the Qagan Qulu ophiolite belt (after Zhang JJ et al., 2015).

6. Genesis and setting of large granitoid provinces (continental growth and deformation)

6.1. Carboniferous-Permian granitoids in the Central Asian Orogenic Belt

A large number of granitoids are developed in the Central Asian Orogenic Belt (Jahn BM et al., 2004; Wu FY et al.,2011), and most of them formed in Carboniferous-Permian time, which are widespread in a planar distribution (Wang T et al., 2017a). Most Carboniferous-Permian granitoids were emplaced in the western part of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt, such as the Altai, East and West Junggar, and Tianshan-Beishan regions. At the same time, these granitoids are accompanied by numerous contemporaneous volcanic rocks,making up of a Large Igneous Province (Xia LQ et al., 2012).The existence of this large igneous province can be further proved by the development of Tarim mantle plume (Zhang HR et al., 2013b, Li ZL et al., 2011), Permian plutons (Han BF et al., 2006), and large volumes of Permian dykes warms.They also provide key evidences for determining the closure of the Paleo-Asia Ocean in the northern Xinjiang region before Permian.

A mass of Carboniferous-Permian granitoids are also distributed in the east part of the southern CAOB, Inner Mongolia and northeast China, but they show different characteristics. Carboniferous granitoids in this area have some similar features, but Permian granitoids in different regions in this area show different characteristics (Wang T et al., 2017a,b).Volume early-middle Permianpost-orogenic alkaline granites(A-type) distribute in the northern of Inner Mongolia, while the early Permian granitoids in the south Inner Mongolia and north margin of North China Craton are more characterized as arc granite. Until late Permian, few A-type granites emplaced in the south (Zhao XL et al., 2017), and the granitic magmatic properties started to change significantly during late Permian which indicates that the Paleo-Asia Ocean in this area probably closed later than that of north (at Middle-Late Permian).

In a region, the Carboniferous-Permian granitoids in south part of CAOB seem to gradually become younger eastward along the main suture zone, which indicates that the eastward closure of the Paleo-Asia Oceanas a scissor-way (Wang T et al., 2017a). Additionally, recent studies suggested that the Carboniferous-Permian granitoids in the east of CAOB are not only formed during the evolution of Paleo-Asia Ocean,but also formed in a subduction setting of the Mongolia-Okhotsk Ocean. These Carboniferous-Permian granitoids in the Central Asian Orogenic Belt are the products of dual tectonic settings.

6.2. Late Mesozoic granitoidsin Northeast Asia

Large volumes of late Mesozoic (Jurassic and Cretaceous)granitoids are widespread in Northeast Asia (Fig. 4). In recent years, their spatial-temporal distribution was able to be determined by zircon dating.The Early-Middle Jurassic granites are parallel to the Okhotsk tectonic belt and are characterized by a magmatic migration toward the southeast. These granitoids are probably influenced by the Okhotsk tectonic system (Wang T et al., 2015). The Cretaceous granites,however, are mainly distributed in the NE direction, indicating a migration toward the Pacific Ocean, controlled by the Paleo-Pacific Ocean (Wu FY et al., 2011;Xu WL et al., 2013;Wang T et al., 2017a). The superposition evidence of these two dynamic systems can be provided by this distribution.

Fig. 4. The distribution map of large-scale Late Mesozoic granitoids in the Northeast Asia.

According to available geochemical data of these major elements, characteristics of granitic magma from the Jurassic to the Cretaceous change from a high-K calc-alkaline to a high-K calc-alkaline-shoshonitic, from I-type to highly fractionated I-type and A-type, and from high Sr/Y values to low Sr/Y values (Wang T et al., 2015). This evolution provides further evidence for the large-scale Northeast Asian crustal extension and thinning in the world. These findings also provide new evidence for the Yanshanian metallogenic explosion. The crust changed from thickening to extension and thinning can be evidenced by magma evolution, combined with the Cretaceous metamorphic core complex and the development of the extensional basin (Wang T et al., 2012).

Overall, in Northeast Asia, and particularly in the west of the Songliao Basin, the formation of Early-Middle Jurassic granite is probably related to the closure of the Mongolia-Okhotsk Ocean and its related effects. Moreover, the far-field effects of the subduction of the Paleo-Pacific plate superposed in the east of Songliao Basin (Wang T et al., 2012). During the Early Cretaceous, the Mongol-Okhotsk orogenic belt started to extension and collapse, and superposition of the backarc extension of the Paleo-Pacific Ocean.The whole of northeast Asia became an extension system in which voluminous Cretaceous granites were formed. Based on the studies of the large-scale Cretaceous granites in the southern part of the Great Xing’an Range, large-scale Cretaceous magma can be considered as a result of the upwelling and upward propaga-tion of fluid which was caused by the trapped oceanic slab in the mantle transition zone.

6.3. Genesis and tectonic settingof Mesozoic granitoidprovince in south China

6.3.1. Genesis and settingof the Early Mesozoic granite

Mao JR et al. (2014) pointed out that Indosinian granitoids in South China can be considered as a product of the multi-block convergence and multi-direction compression-extension.The A-type granite-syenite group (239-221 Ma) could have been formed after the collision between the Sibumasu Block and the Indosinian Block at the Hainan Island.However, the A-type granite and aegirine-augite syenite association (232-215 Ma) along the coast eastern Zhejiang (Sun Y et al., 2011; Li S et al., 2012 ; Mao JR et al., 2013c) could have been formed after the collision between the Paleo-pacific plate and Eurasian Plate. The typical gabbro-granite-orthoclase-alkaline A-type granite group in the Sulu-Korea region (219-208 Ma) could have been formed after the collision between the North China Plate and the Yangtze Plate. In the South China Inland and Wuyi-Yunkai Mountain belts, the ages of the rock formations gradually get younger from the south to the north. This can be considered as a result of the compressive stress that was transferred from the south to the north in wake of the collision between the Indosinian Block and the South China Plate. Recently, most studies arrived at the same understandings on the formation of Indosinian granite and the dynamic tectonic background of the multi-blocks convergence and multi-direction compression-extension(Wang XX et al., 2013a,b; Chen CH et al., 2011; Mao JR et al., 2014).

6.3.2. Genesis and setting of the Late Mesozoic granite

A series of long-term studies on Mesozoic granite in five provinces of southeastern China was carried out by a research team at Nanjing University (Zhou XM et al., 2000, 2006,2007). The major results include: (1) Establishment of a twostage subduction-extension model of the genesis of Mesozoic granite, illustrations of the transformational relationship between the Tethys-Pacific tectonic regions, and determination of the tectonic background of the Mesozoic extension in Cathaysia Block; (2) Revealing the “material source” relationship between the granite genesis, the mantle-curst interaction and magma mixing, and its related “heat source” problem; (3)Emphasizing the importance of the magmatic-hydrothermal process to the W-Sn rare metal mineralization. The above studies have solved the key scientific issues of Mesozoic granite genesis in Cathaysia Block, while developing the basic metallogenic theory of the granite, and rebuilding the Mesozoic tectonic framework for Southern China. These studies provided the basic geological basis for the strategic layout of the search for Metallic minerals.

In addition, Li ZX and Li XH (2007) proposed a flat subduction and separation model to explain the formation background of the voluminous Mesozoic granitoids in South China. Zheng YF et al. (2013) emphasized that the magma originated from the Precambrian crust of the orogenic belt and the mantle lithosphere, along with the magma activity influenced by the subduction/recession of the Pacific Plate, can be considered as the reconstruction of the paleo-continental margin material under the new continental tectonic background.Jiang YH and Wang GC (2016) and Xia Y et al.(2016) further determined the mechanism of multiple subduction/recessions of the Paleo-Pacific plate. Liu H et al., (2016) concluded that the middle Jurassic (175 ± 5 Ma) granite was formed under tectonic background of Plate subducting approximately from south to north.

During the Cretaceous time (approximately 120 Ma) the Paleo-Pacific Plate's subducted westward forward, and in the middle of the Cretaceous (85 ± 5 Ma), South China had become a passive continental margin (Chen CH et al., 2010), and at the same time, the roughly contemporary the Guangdong-Fujian-Zhejiang coast and eastern Taiwan had completely different tectonic settings. The former was aextensional intraplate setting, and the latter can be considered as an extruded arc-land collision environment. This multi-stage subduction also lead to the accumulation of multi-stage magma and other elements (W, Sb, Sn, and Fe), which resulted in that the formation of a massive magmatic mineralization system (Sun WD et al., 2013). Sun WD et al.(2013) pointed out that the lower reaches of the Yangtze River may had experienced the oceanic ridge subduction or plate separation in the Late Mesozoic period, which lead to the mineralization of A1-type and A2-type granites.

The comparison and summary of the characteristics and background of Mesozoic granitoids in the eastern China were accomplished by Li XH et al., (2003), Yang JH et al., (2005)and Wu FY et al., (2012). Their results are mentioned below:(1) The geochronology of the Yanshanian granites in northeast China, North China, and South China can be divided into Early-Middle Jurassic (Early Yanshanian) and Early Cretaceous periods (Late Yanshanian); (2) Yanshanian granites are characterized by I-differentiation-type and A-type, a differentiation from the other typical areas in the world; (3) Early Yanshanian granites in the northeast China and North China were formed under the extruded tectonic background of plate subduction, and the Early Yanshanian granites in South China were related to the crust re-melting caused by the extension of lithosphere or the underplating of mantle magma.

The above results reveal the unique geodynamic process of the formation of Yanshanian granite in eastern China,which can provide a new constraint for further mineral exploration related to different types of granite in eastern China. Besides, it has enriched the scientific connotation of granite in many fields, such as the formation of granite and the evolution of the mainland. These studies also enriched the reputation and influence of the Chinese scientists that were promoted.

7. Framework of evolution of granitoids in China and their settings of continental assembly and breakup

Previous studies have summarized the general situation of granitoids (Hong DW et al., 2007), and some spatial-temporal distribution maps of granitoids have been compiled. Recently, rock assemblages and tectonic facies and setting of granitoids were revealed by Granite Geotectonic Map of China (Deng JF et al., 2016), which can be considered as an important progression on the combination of granite mapping and tectonic research.

According to the measurements and the collection of 7000 new zircon ages, a Digital Granite Map of Main Orogenic Belt and the Granite Map of China were compiled (Fig. 5).From the view of continent assembly and breakup, comparisons and comprehensive analysis of orogenic granitoids in Central Asia, Central Chin, Circum-Pacific and the Tibetan plateau were conducted. Moreover, the characteristics and development processes of granitoids under the Paleo-Asian ocean system, the Paleo-Pacific system, and the Tethys ocean system were explained, along with evidence that can be used for exploring Asian tectonic evolution, especially for the study on assembly and breakup of continent.

The characteristics of granitic magma evolution and their related tectonic evolution in the four major orogenic belts(systems) (CAOB, CCOB, Tethys, and West-Pacific tectonic orogenic systems) were further explained. For example, it was revealed that the overall Paleozoic granitic plutons in the CAOB migrated and evolved from the north to the south.However, the Late Paleozoic granitoids are distributed with large areas, showing coeval and multiple tectonic setting. In the China Northern Orogenic Belt (southern CAOB), the spatial-temporal evolution characteristics of the Permian granite in Southern Tianshan reveal the scissor-like closure process of the Paleo-Asian Ocean from east to west (Huang H et al.,2015). The inward migration of the Permian-Triassic magmatic rocks in the Mongol-Okhotsk region obtained from numerous data analyses can be considered as a record of roll-back of the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean (Wang T et al., 2017a). The extent and influence of this tectonic setting in the Permian can be determined by this progress. Besides, the Southeast migration of magma is a reflection of the Paleo-Asian Ocean system. Another progress is the summary of the characteristics of the Triassic granite in Central Asia and the division of five magma belts, which reveal the two stages of evolution (calcalkaline to high-K calc-alkaline- alkaline) and various settings from the Okhotsk margin to the Altai intra-plate settings(Li ZL et al., 2013). The magmatic evolution and migration,and the effect of stagnant lab on the magma source in the Permian-Triassic at the southern margin of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt was revealed, providing new evidence for the final closure timing of the Paleo-Asian Ocean in the Solonker-Xar Moron tectonic belt (Li S et al., 2016). During the Late Mesozoic, the evolved characteristics from the Jurassic contraction-related granite to the Cretaceous extension-related reveal the superposition of Mongolia- Okhotsk and the Paleo-Pacific tectonic systems. In the China Central Orogenic Belt,the spatial-temporal evolutions of granite in the Neoproterozoic, Paleozoic, Early Mesozoic, and Late Mesozoic were determined, in response to subduction to collision evolution(Wang XX et al., 2013a,b; 2016).

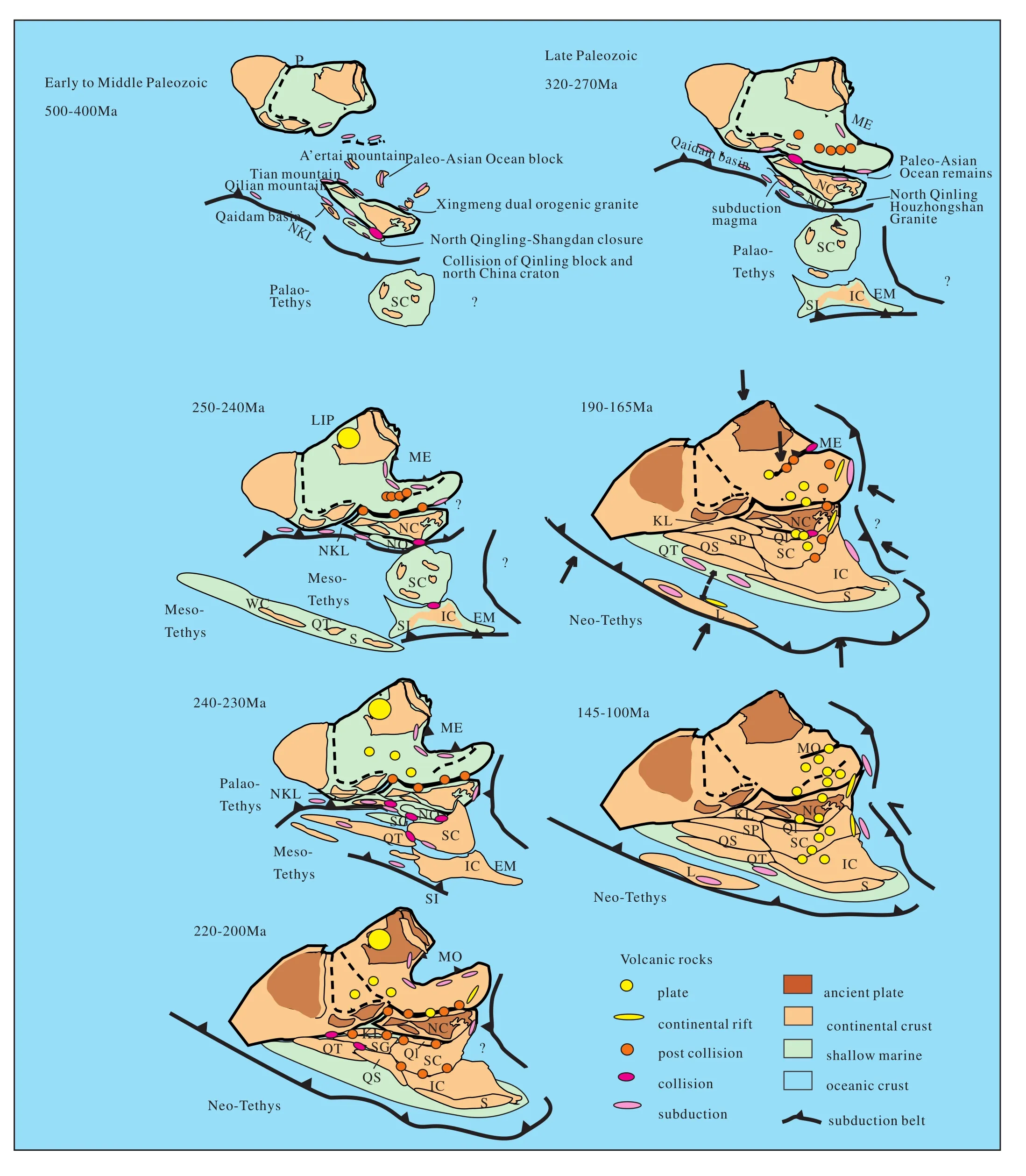

The similarities and differences, and spatial-temporal evolution of granites in the northern and central orogenic belts, were compared and analyzed, revealing the processes of simultaneous subduction and closure in the Paleozoic Paleo-Asian Ocean and the Paleo-Tethys Ocean. Various tectonic settings for the Paleozoic and Early Mesozoic granite belts could be demonstrated from the perspective of the Northeast Asia continental assembly (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. A map of Asia Mesozoic granite and related intrusive rocks (modified from Wang T et al., 2014).

Based on the summary of spatial-temporal evolution of various orogenic granites, the major granitic magma events and related tectonic settings in China were preliminary summarized. According to the digital maps, the basic framework of tectono-magmatic evolution in China and even Asia was described. Tectonic evolution and composition characteristics of the deep crust in the Paleozoic, Early Mesozoic (Triassic),and Late Mesozoic (Jurassic, Cretaceous) can be preliminarily summarized. Further discussion can be carried out on evolution and the tectonic setting of Mesozoic granite in Asia and the assembly and breakup of Chinese continent.

In the Neoproterozoic, granite belts were mainly distributed in the Yangtze Block, the CCOB, and the surrounding area of the Tarim Block. The age of the contraction-related granite belt is 1000-900 Ma and 850-700 Ma represents the age of the extension-related granite belt, in response to assembly and breakup of Rodinia supercontinent. In the Qinling Mountains, the strongly-deform S-type granite (960-900 Ma) is evolved from weakly-deform I-type to non-deform A-type, revealing the convergence setting from the collision to post-collision (Wang XX et al., 2013a,b).

In the Early-middle Paleozoic, the accretion and closure process of the Paleo-Asian Ocean can be reflected by the Early-middle Paleozoic granite in the CAOB. The setting of the late Paleozoic granites in Northern China may be a complex, with the oceanic and continental setting coexisting, accompanied by development of the mantle plume. Moreover,both intraplate granite and continent-marginal granite have developed in this area. In the Central Orogenic System, the late Paleozoic-Early Mesozoic granite is a product of the subduction and closure of the Paleo-Tethys Ocean.

In the Early Mesozoic, granitoids could be classified into two stages: 250-230 Ma and 230-200 Ma, respectively. The early granitoids was formed in the subduction of the Meso-Tethys and Mongolia-Okhotsk Ocean. The later granitoids are related to the collision between the North-South China continents and Indochina blocks with the Yangtze block, suggesting that the final amalgamation of the China and adjacent continents were completed in 220-200 Ma. According to the integrated results mentioned above, from the perspective of the spatial-temporal evolution of Asian Mesozoic granite, the framework of Mesozoic assembly in China and the adjacent continents can be outlined (Fig. 6). This contributes to the discussion of the assembly of the China block and adjacent continents, as well as the reconstruction of Pangea (Wang XX et al., 2013a,b). The response of the final assembly can be indicated by the granite belts in the entire Chinese (and adjacent)continents, possibly revealing the hysteresis of the assembly of Pengea with the China.

Fig. 6. The formation and evolution of Mesozoic-Paleozoic granites in China and adjacent areas, and the relationship of the continental assembly process (modified from Wang T et al., 2014; assembly process is referenced by Wan TF and Zhu H, 2007; Metcalfe I, 2013; Stampfli GM et al., 2013). The Paleo-Asian Ocean and Proto-Tethys Ocean were on the both sides of the Paleozoic-Mesozoic the Tarim, Alxa, and North China Craton. The Central Asian Orogenic Granite Belt was formed by the subduction and accretion of the Paleo-Asian Ocean. The China Central Orogenic Belt was formed by the subduction of the Proto-Tethys and Meso-Tethys and the collision of multiple blocks such as the China block, etc. ME: Mongolia-Okhotsk; NC: North China Craton; SG: Songpan-Ganzi; SC: South China Block; KL: Kunlun; NKL: North Kunlun; NQ: North Qinling; WC: West Cimmerian; SQ: South Qiangtang; I: Indochina Block; L: Lhasa Block; SL: Simao; S: Sibumasu Block;EM: East Malaya Block.

In the late Mesozoic, granites were mainly distributed in the eastern part of Asia and Tibetan Plateau, controlled by the three dynamic systems of the Mongolia-Okhotsk Belt, the Pacific Ocean, and the Neo-Tethys. Voluminous Late Mesozoic granites in eastern China are influenced by the Mongolian-Okhotsk belt to north and the Paleo-Pacific Ocean to south.Overall, the features of the granitoids were changing from Jurassic compression thickening to Cretaceous extension thinning (Wang T et al., 2015).

8. Granitoid tectonics

A granitoid pluton can be regarded as a tectonic marker or geological body, and abundant tectonic information can be extracted from it to explore and solve some geotectonic problems. Therefore, granitoid tectonics, such as its connotation,research idea, research content, and development direction, is proposed here based on the above studies (Wang T et al., 2017a).