Meta-analysis of the Eff i cacy and Safety of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) in the Treatment of Depression

Yanyan WEI, Junjuan ZHU, Shengke PAN, Hui SU, Hui LI, Jijun WANG

1. Introduction

Depression is a clinically common form of mental illness characterized by depressive mood and / or loss of interest and accompanied by mental disease with somatic and neurophysiological symptoms.[1]WHO reports that depression is one of the major risk factors for years of disability.[2]It is predicted that by 2020,depression will jump from 4th place to the 2nd leading cause of global burden of disease.[3]The pathogenesis of depression in not yet clear, and the treatment for depression is still mainly pharmaceutical; however,many patients treated with pharmacotherapy do achieve ideal outcomes. There still remains a significant portion of patients (20%-30%) who despite having received sufficient dosage and completed the prescribed course of treatment still do not see a total alleviation of depressive symptoms. Although new antidepressants continue to emerge, the side effects of medication therapy are still not completely avoidable.[5]

With the development of imagining technology,research findings show that patients with depression may have organic brain damage. This phenomenon indicates that the pathology of depression is probably related to organic brain damage. Fortunately, thanks to the introduction of a series new techniques in neural modulation, advancements have been made in the treatment of depression. Among these modulation techniques is repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Developed in the mid 1980s, the technique is a bio-stimulation that affects and changes the function of the brain. By making use of the time varying magnetic fi eld to act on the cerebral cortex and creating an induced current in the cerebral cortex that alters the action potential of cortical neurons, rTMS is a biological stimulation that affects brain metabolism and neuronal electrical activity. Based on the mechanism of TMS, the induced pulses of current can depolarize neurons and when applied repetitively (an approach known as rTMS) can modulate cortical excitability through altering the parameters of stimulation[6]to repair white brain matter or neurologic damage, thus attaining therapeutic effects.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation can be divided into high-frequency stimulation (5-20Hz)and low-frequency stimulation (≤1Hz). Depending on the frequency, the high frequencies can increase cortical excitability, and the low-frequency suppresses excitability.[7]Recently, rTMS and fMRI (functional magnetic resonance image, fMRI) were combined to identify cognitive-related brain areas[8-10]responsible for executing cognitive tasks. And with the development of technology, deep transcranial magnetic stimulation has gradually become an effective treatment for mental illness[11,12]Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation has been shown to be effective for the treatment of affective disorders such as depression in many randomized controlled studies,[13]but most of the sample size in these studies was relatively small.As a result, general consistent conclusions cannot be drawn across these studies.[14]Clinicians and patients believe that rTMS is a way to treat depression, but there is still a need for more evidence to support the determination of optimal parameter settings for treating depression. Thus, in this study, we compare the efficacy of antidepressants combined with rTMS treatment versus sham controlled rTMS in treating patients with depression.

2. Methods

2.1 Literature screening and retrieval strategy

In this study, we used the keywords: “抑郁”(depression)and “经 颅 磁 刺 激 ”(TMS) to retrieve articles from the Chinese databases: Chinese National Knowledge infrastructure (CNKI), Wang Fang Data, and China Science and Technology Journal Database (CSTJ); and used the keywords: “depress*”, “transcranial magnetic stimulation”, “TMS”, “rTMS” to retrieve from the following English language databases: Embase, PubMed,the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, PsycInfo. We searched for Randomized Control Trials (RCTS) that study the efficacy and safety of rTMS in the treatment of depression, with the date of publication on or before 5 January 2017.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This study included the randomized sham controlled studies of the efficacy and safety of RTMS in the treatment of depression and evaluated the efficacy and safety of the combination of RTMS and antidepressants in the treatment of depression.

2.2.1 Objective of study

All subjects that participated in the study groups were classified according to one of the following psychiatric diagnostic standards: International Classification of Diseases (ICD)[15], Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)[16], or the third edition of the Chinese Mental Illness Diagnostic Standard (CCMD-3).[17]

2.2.2 Included study types

The included studies were randomized controlled trials in which the study group used rTMS intervention and the control group used rTMS sham coils or flipped stimulation coils at a certain angle to achieve the sham stimulus effect. In the outcome, the extent of improvement and side effects in the patients with depression was measured. The research program design types are as follows: ① left high frequency stimulation VS. left high frequency sham stimulation;② right low frequency stimulation VS right low frequency sham stimulation; ③ left high frequency stimulation (combined with medication treatment)VS left high frequency pseudo-stimulation (combined with medication treatment); ④ right low-frequency stimulation (combined with medication treatment) VS right low-frequency sham stimulation (combined with medication treatment / psychotherapy).

2.2.3 Exclusion criteria

Studies with the following contents were excluded:

(1) Experimental studies using animals; (2) senile depression, postpartum depression, post-traumatic stress disorder with depression; (3) review and case report studies; (4) repeatedly published studies; (5)improvement of non-depressive symptoms, such as,changes in cortical excitability, change in cerebral hemodynamic characteristics, or cognitive functions etc. at treatment outcome as the primary outcome indicators; (6) using blank control as controlled group or studies involving electroconvulsive therapy; (7) studies with unspecified randomization methods and crosssectional design were excluded.

2.3 Literature screening and data extraction

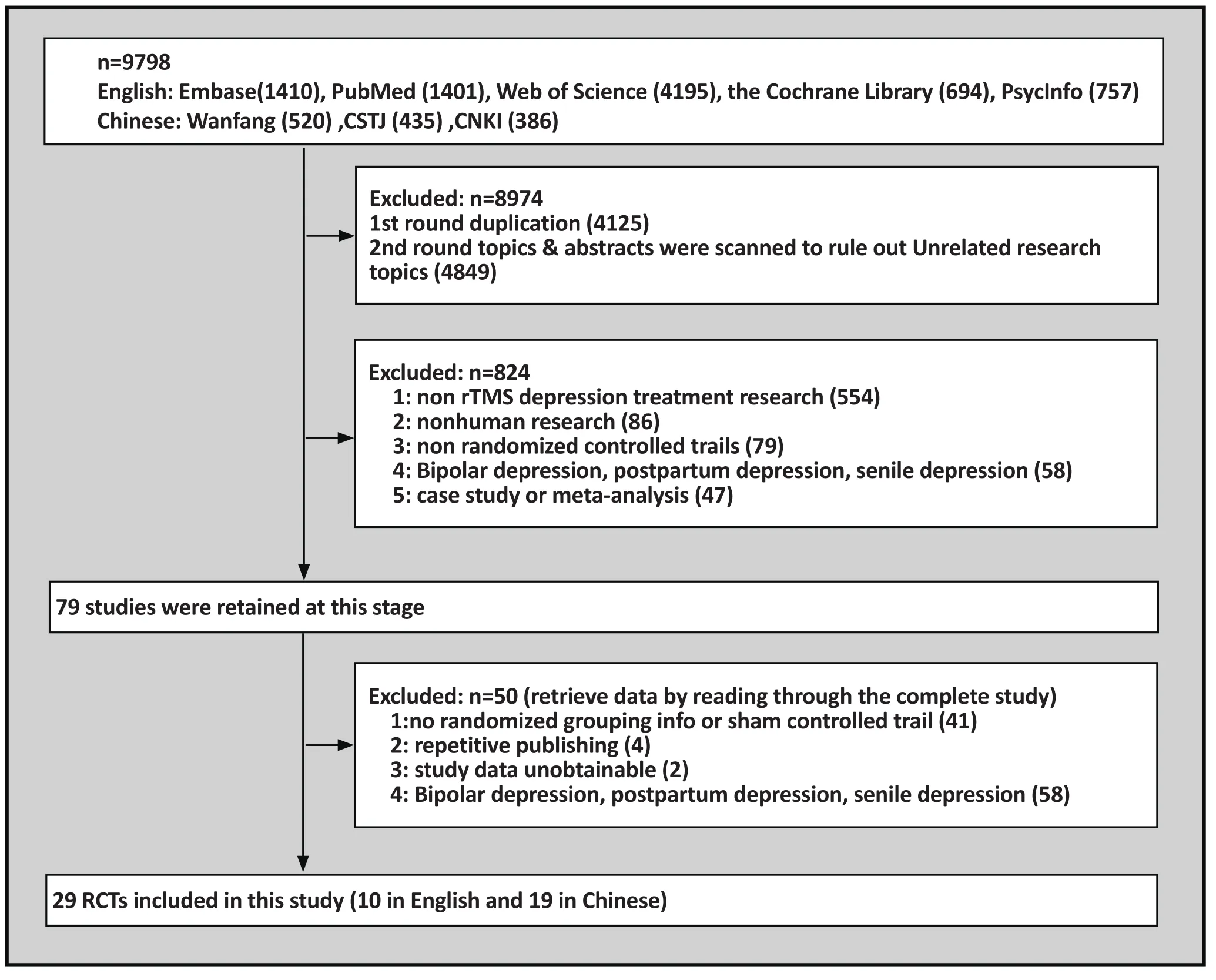

Two researchers used the same inclusion and exclusion criteria to screen the literature retrieved from the electronic databases. We used the following screen and extraction process: (1) Check for duplicates from the retrieved articles. (2) Titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles were separately screened by two researchers to exclude those articles unrelated to this study. (3) the full text of remaining articles was read to further screen out articles according to listed inclusion and exclusion criteria. (4) Any disagreements about whether articles shoul be included or excluded were discussed among the two researchers, in the case where no consensus could be reached, a third senior research was consulted to make the final determination (see Figure 1 for study fl owchart). The included information extraction form was developed by Wei Yanyan. The two researchers extracted the research data separately, and the extracted information included categories such as study authors, year of publication, sample size, true stimulus frequency, stimulus site, stimulus intensity (%of resting motor threshold), sham stimulation mode,and treatment cycle.

Figure 1. Literatures screening flowchart

2.4 Risk of Bias assessment

A risk of bias assessment was carried out for all RCTs included in this study according to the guidelines put forth by the Cochrane Collaboration Network. The assessment mainly includes the following seven aspects:(1) random sequence generation (selection bias); (2)allocation concealment (selection bias); (3) Blinding of the subjects and the researcher (implementation bias); (4) Blindness of measurement of outcomes(measurement bias); (5) Integrity of the results(attribution bias); (6) Selective reporting of outcomes(reporting bias); (7) Other bias. All risky information included in this study was evaluated separately by two investigators and was discussed and agreed to by a third researcher in cases of disagreement.

2.5 Outcome Measures

Primary outcome measures: Assessment of efficacy of rTMS in treating the depressive symptoms of patients with depression

The outcome measures included in this study were score assigned with 1st priority in the study: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) scores measured before and afer the intervention, Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score before and afer the intervention of rTMS as the second priority score,and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score change before and afer rTMS intervention as the third priority score.

Secondary Outcome Measures: Improvement in overall function, side effects, safety, and tolerability of treatment.

To assess the improvement of overall function of patients with depression after rTMS intervention, we used mainly the scores of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale(BPRS) and Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)scores to calibrate the change. Safety was assessed by comparing the differences in adverse reactions between the two groups. The comparison included the general adverse reactions such as headache, nausea, and insomnia and serious adverse reactions such as epilepsy.The acceptability of rTMS treatment was compared by the dropout rate between the two groups during the treatment courses.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Revman 5.3 statistical sofware, and heterogeneity was assessed using the χ 2 test. When all studies met the statistical homogeneity(p> 0.1, I2<50%), we used the fixed effects model for Meta-analysis of the treatment effect and side effects;otherwise, we employed the random effects model for Meta-analysis and took the source of heterogeneity into consideration. For the combined effect analysis, we used Standardized Mean Deviation (SMD), Relative Risk (RR)and its 95% CI. The fi nal calculated result was shown in the Forest Plot. Cochrane was used for risk assessment and funnel plot for observing publication bias. At the same time, Stata12.0 linear regression method was designated to detect funnel chart symmetry.

3. Results

3.1 Literature screening process

Using the search strategy specified in above, we retrieved from 5 English databases and 3 Chinese databases a total of 9798 related articles. Endnote Document Management Software was used for exclusion screening, and the following studies were excluded based on the following: duplicate study- 4,125 studies; articles with irrelevant research purposes- 4,849 studies; did not meet inclusion criteria- 824 studies;unknown process in grouping or without randomized sham controlled trials- 45 studies; and repeatedly published- 2 studies[18,19]and duplicate reports from the results of 2 master’s theses.[20,21]In addition, a study was excluded because only the lowest, highest, and median scores for the Hamilton Depression Inventory score for TMS interventions were given, leaving the mean and standard deviation unspecified as well as the side effects and dropout rate unreported.[22]In the end 29 articles were included in this systematic review.[18,23-50]

3.2 Characteristics of included studies

All subjects included in this study were diagnosed with depression with one of the following diagnostic criteria:DSM-IV, CCMD-3, or ICD-10. Three studies were with the subjects that met the diagnostic criteria for refractory depression, and in many cases, the parameters setting in the rTMS treatment were the high-frequency stimulus applied on the left hemisphere. Four of the studies used 1 Hz of low-frequency stimulus over the right hemisphere,[24,28,31,43]and in a 2010 article, the stimulus frequency 5 Hz and 20 Hz were utilized alternately to perform interventions,[26]but to reach equilibrium with the sham controlled group, the subjects included in the sham control were also equally distributed using the frequencies of 5 Hz and 20 Hz. In Xie et al. (2015) 30%resting motor threshold was used, the intensity of the stimulation in all other studies was controlled within the range of 80%-120% of resting motor threshold. In all the included studies, the shortest treatment period was 2 weeks, and the longest was 8 weeks. Twelve studies used sham coil as a means[18,29,31-35,44,46,47,49,50]to setup the sham controlled group; in the remaining studies,the coil was rotated 45, 90, or 180 degrees to achieve the effect of sham therapy, but in George et al., how the sham stimulus control was achieved was not specif i ed.[36]

During the entire course of rTMS treatment, all subjects maintained the original type or dose of medication therapy or received a specific dose of medication therapy afer a period of evaluation.

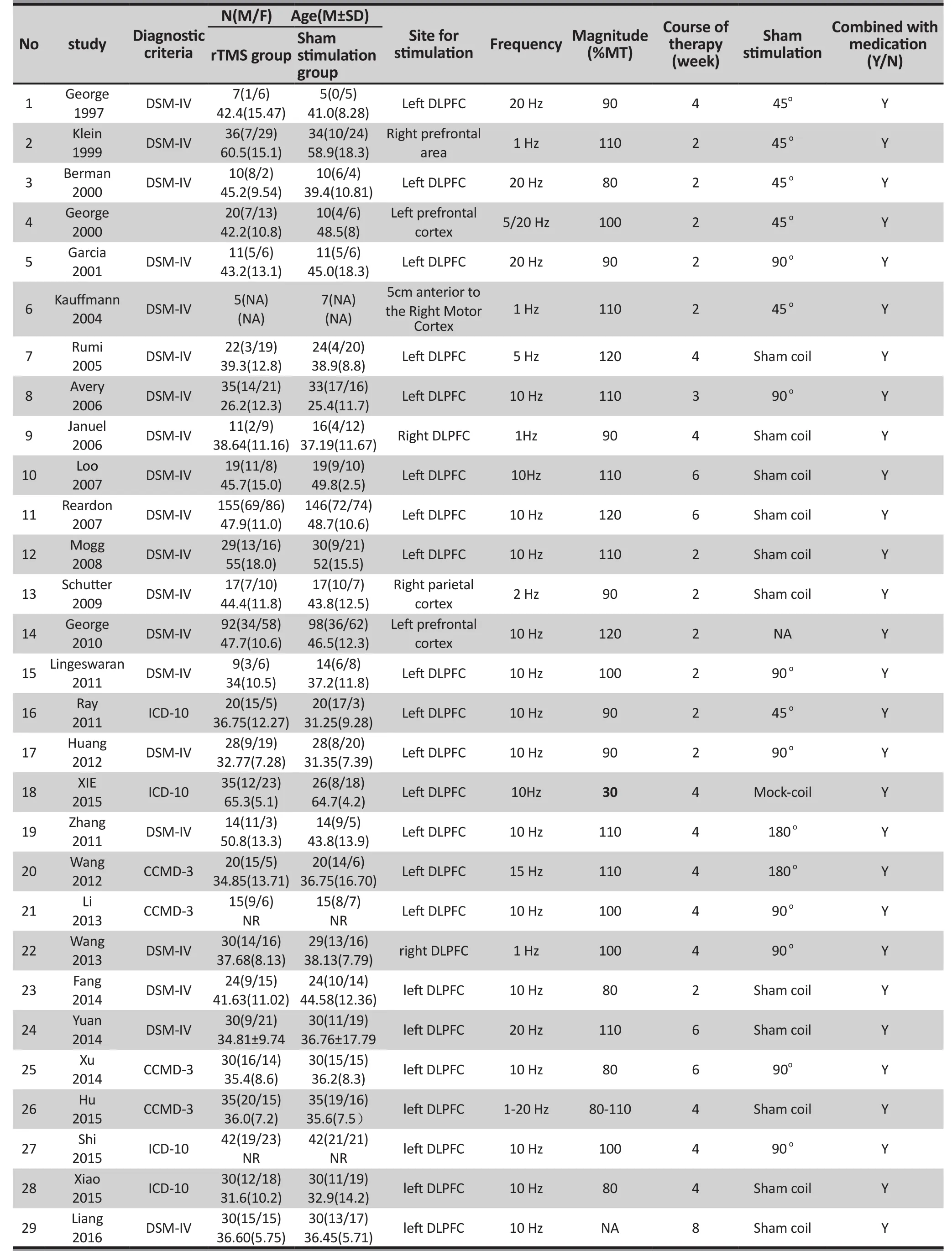

Table 1. Basic information of the included studies

3.2.1 Quality of the included studies

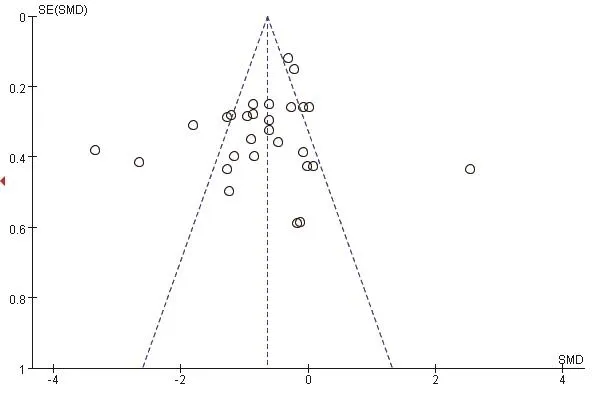

In the literature screening process, the studies with unspecified conditions for randomized grouping or with high risk in random grouping were excluded;therefore, in quality assessment of the included studies(see figure 2), all the included studies were presented with conditions depicting the randomized grouping and were rated as “Low risk”. Five studies qualified their randomized allocation concealment,[30,34-37]and the selection bias was rated as “Low risk.” 11 studies used blind methodology with their experimenters and researchers[18,25,27,29,30,32-34,36,37,43]and performance bias was rated as “Low risk.” One study was selective in reporting their results,[27]the reporting bias was rated as “High risk”. Studies with unclear information were rated as having “Unclear risk”. Figure 3 is a funnel plotthat incorporates the trials studying the efficacy of the therapy that uses medication combined with rTMS in the treatment of depression. The existence of an asymmetrical trend may due to publication bias or other causes.

Figure 2. Risk of bias assessment of 29 included studies based on Cochrane Collaboration tool

Figure 3. Funnel plot to identify the presence of potential publication bias in 29 included studies on rTMS combined with antidepressant medication in treating depression

3.3 Treatment effect

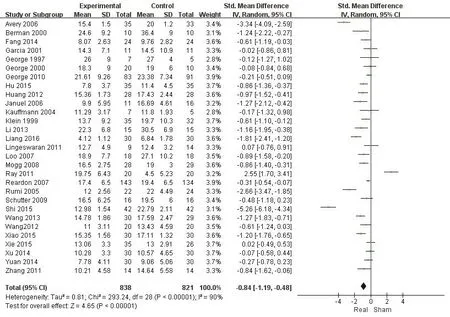

Of the 29 included studies, the primary outcome measures were the Hamilton Depression Symptom Inventory (HAMD) score before and after the intervention with 6 studies using 21 items on the HAMD scale; 3 studies using 24 items on the HAMD scale; and the remaining studies using 17 items on the HAMD scale. The heterogeneity of the included studies was high (χ2= 293.24, I2= 90%); therefore, the random effects model was used for meta-analysis. The results show that efficacy of the rTMS combined with antidepressant therapy in treatment of depression is significantly higher than the sham stimulation group(SMD = -0.84, 95% CI: -1.19 ~ -0.48), and the difference was statistically significant (Z = 4.65, p< 0.01) See Figure 4. According to the GRADE score, as the main outcome measure, i.e. the improvement in symptoms of depression in rTMS interventions, the overall quality level of evidence is “moderate” as shown in Table 2.

3.4 Subgroup analysis

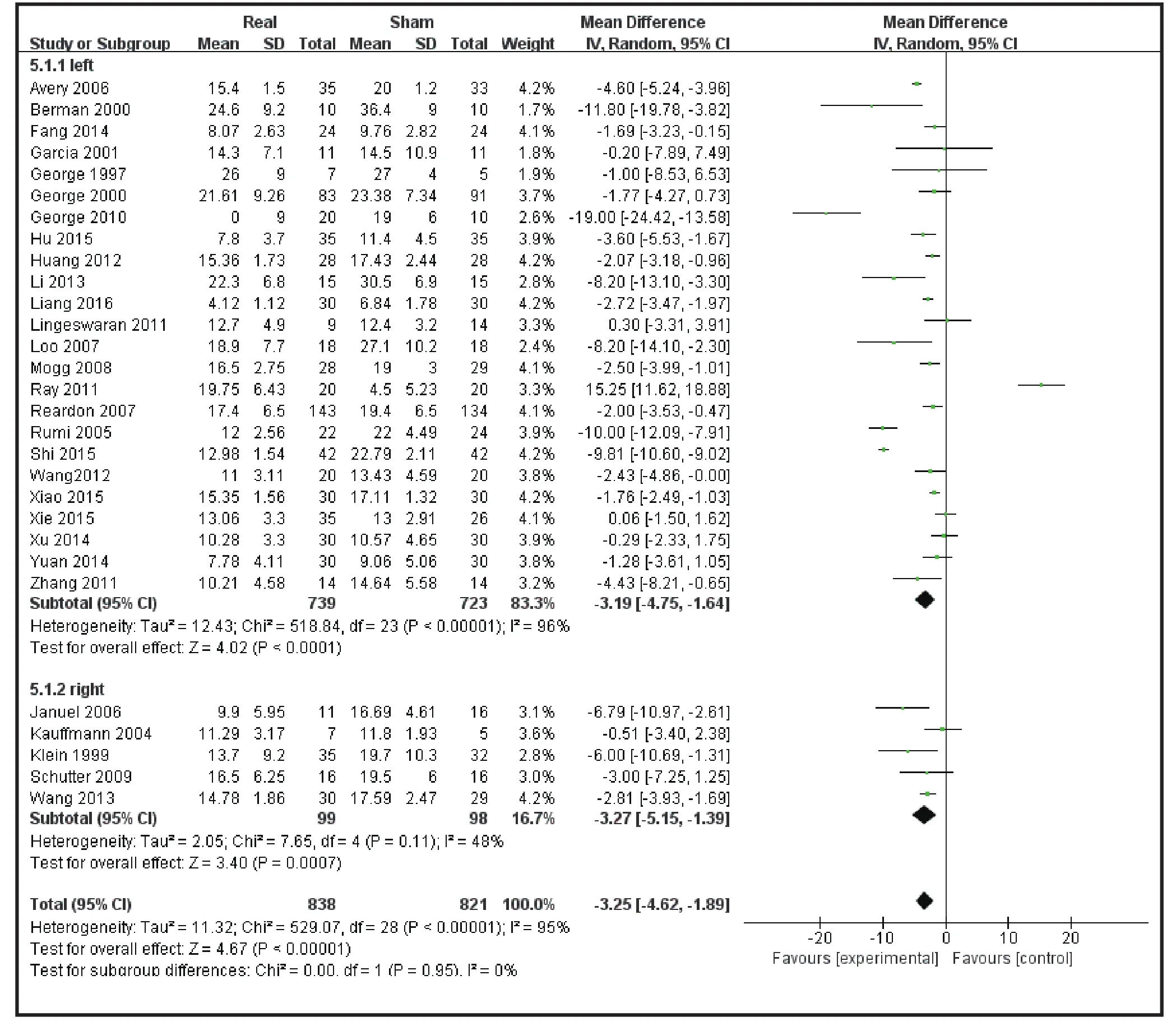

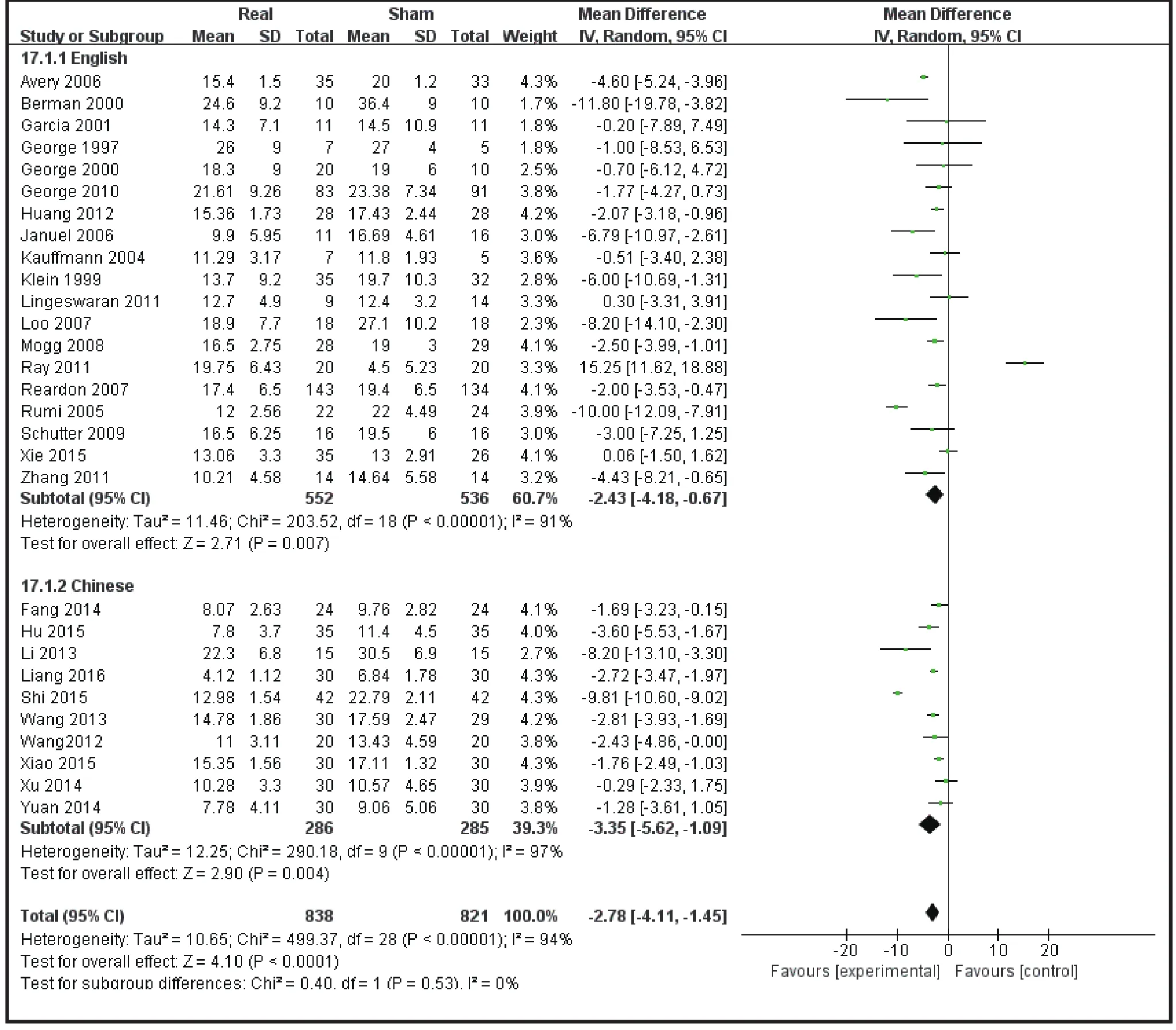

According to the sites of stimulation (the left hemisphere and right hemisphere) the studies are divided into subgroups. The results of subgroup analysis were χ2= 518.84, I2= 96% and χ2= 7.65, I2= 48%. The heterogeneity results were χ2= 529.07, I2= 95%, p<0.01(see Figure 5), suggesting greater heterogeneity with the left hemisphere stimulation site. According to the administered frequencies of stimulation the studies were divided into two groups: a group with highfrequency stimulation >1 Hz and a group with lowfrequency stimulation ≤1Hz, and the sub-group analysis results were χ2= 489.56, I2= 95% and χ2= 7.65, and I2=61% respectively. The combined heterogeneity results were χ2= 499.37 and I2= 94%, p<0.01 (see Figure 6).Subgroup analyzes were performed according to the duration of the treatment course (i.e. treatment course≤4 weeks and> 4 weeks). The subgroup analysis results were χ2= 471.26, I2= 95% and χ2= 9.62, I2= 58% Post hoc heterogeneity resulted in χ2= 502.28, I2= 94%, p<0.01 (see Figure 7). Subgroup analyzes were performed over the differences between studies published in Chinese-language journals and studies published in English-language journals. The subgroup analyzes showed χ2= 203.52, I2= 91%, χ2= 290.18, and I2= 97%,respectively. The combined heterogeneity was χ2=499.37, I2= 94%, p <0.01 (see Figure 8).

Figure 4. Meta-analysis forest plot showing efficacy of rTMS combined with antidepressant medication treatment versus sham control treatment in treating depression

Table 2. GRADE quality of evidence assessment of individual outcome indicators for the efficacy of rTMS combined with antidepressant medication therapy in the treatment of depression

Figure 5. Subgroup analysis forest plot of stimulation on the left hemisphere versus stimulation on the right hemisphere

Figure 6. Forest plot of subgroup analysis of high frequency stimulation vs low frequency stimulation

3.5 Heterogeneity Meta-regression

Given that heterogeneity may be due to the differences in the severity, age, and prescript stimulations parameters of the subjects, linear regression was used to assess the relationship between heterogeneity and baseline depression, age of participants, and stimulation parameters. Baseline HAMD scores, intensity of stimulation, frequency of stimulation, and stimulation regimens were included as factors in the regression model to assess the effect on heterogeneity. Baseline HAMD scores and regression analysis of age alone showed P values of 0.993 and 0.142, suggesting that the severity and age of patients with baseline depression were not a contributing factor to heterogeneity. Then the stimulation intensity, stimulation frequency and stimulation treatment course were included in the regression model to get the p value of 0.052, 0.536 and 0.047 respectively. The intensity and stimulation treatment course may be related factors causing heterogeneity. Among the two factors, when the course of treatment was put into the regression model, that explained 12.8% of the variation in heterogeneity.

3.6 Meta-analysis of adverse reactions

None of the included studies reported serious adverse effects. Twenty of the studies reported their subjects experienced slight discomfort including: headache, pain in the stimulation site, muscle tension, dizziness, lossof interest et cetera. Of the 690 subjects in the true stimulation treatment group, 319 reported discomfort,and 108 of 663 subjects in the sham controlled group reported discomfort. The included studies were statistically homogenous (χ2= 25.60, p= 0.06, I2=38%), thus a statistical analysis using the fixed effects model was performed. The results showed that rTMS combined with antidepressants in the treatment of depression has a higher incidence rate of side effects,RR = 1.96, 95% CI: 1.47 ~ 2.61. (Figure 9)

Figure 7. Forest plot showing Subgroup analysis of course of treatment≤4 weeks VS course of treatment>4 weeks

3.7 Meta-analysis of dropout rate

Twelve included studies reported participant withdrawal, and meta-analysis of the withdrawal cases data was performed. The results showed good homogeneity among the studies (χ2= 6.76, p = 0.82, I2=0), and were analyzed using the fixed effects model.There were no significant differences between the two groups (27 cases in the stimulus group and 22 cases in the sham controlled group), the difference was not statistically significant (RR = 1.27, 95% CI: 0.75-2.12, Z =0.89).

4. Discussion

4.1 Main findings

Although pharmacotherapy is still the most commonly used treatment for depression, rTMS treatment for patients with refractory depression is an available option. The results of this study show that rTMS treatment of depression has a higher incidence rateof side effects, because the included studies use selfreporting methods to collect data on side effects from the subjects and seldom use scales for quantitative assessment. Also, the side effects disappeared shortly a fer treatment.

Figure 8. Forest plot showing subgroup analysis of efficacy in English studies vs the efficacy in Chinese Studies

Although there are many meta-analyzes on the efficacy of rTMS in the treatment of depression, most of them are confined to the English literature. The present study focused on the efficacy of rTMS versus the sham control in the treatment of depressive symptoms.Compared with the previous meta-analyses, this study has larger sample size that consists of 29 studies and a total sample size of 1659 subjects and included Chinese literature, of which 10 studies were randomized controlled trials published in Chinese, and the sample size of 571 cases in these Chinese studies accounted for a certain percentage of the total sample size. The quality of evidence of GRADE for the primary outcome measure(treatment effect) was “moderate,” and the study of rTMS in combination with drug therapy for depression requires further improvement in the quality of studies;side effects and dropout rates to show the acceptability of using rTMS to treat patients with depression.

4.2 Limitations

Although all enrolled studies employed randomized grouping and blind methods in evaluation, the study outcomes show that heterogeneity among the included studies was high. Heterogeneity was analyzed by using regression model and subgroup analysis, etc. The stimulus frequency, stimulus intensity and duration oftreatment courses were set to the regression model,and the results showed that duration of the treatment course may be one of the factors causing heterogeneity.Similarly, there may be other factors, such as the subjects’ course of disease and number of stimulus train, determining heterogeneity.

Figure 9. Forest plot showing side effects of rTMS combined with antidepressant medication treatment for depression

4.3 Implications

Treatment combined rTMS with antidepressants pharmacotherapy is an important option for clinicians in treating depression. Especially for some refractory cases of depression, rTMS is a feasible option for consideration. However, affecting the treatment,there are many parameters, such as the intensity of the stimulus, frequency of the stimulus train, the site for stimulation, or even the course of treatment.Testing and optimizing these parameters settings and as much as exploring the maintenance effect of rTMS afer treatment still depends on the yet to come representative randomized clinical trials.

Acknowledgement

Thank Jiang Jiangling and Zhu Yikang for their guidance on data analysis of this study.

Funding statement

Shanghai Jiao Tong University Medical Crossing Project (YG2016QN42), Shanghai Municipal Health and Family Planning Commission Research Project(20174Y0013,20134282) National Natural Science Foundation of China (81671332), Shanghai Science and Technology Commission Medical guidance topics(16411965000)

Conflicts of interest statement

All authors claim no conflict of interest related to this article.

Authors’ contribution

Wei Yan Yan was responsible for the literature search;Zhu Junjuan, Pan Shengke, Su Hui were responsible the literature screening; Wei Yanyan, Zhu Junjuan, Pan Shengke, Su Hui were responsible for the data retrieval;Wei Yan Yan and Zhu Junjuan were responsible for the bias assessment; Wei Yan Yan and Zhu Junjuan were responsible for the statistical analysis and writing of this paper; Wang Jijun was responsible planning and guidance on this paper.

1. Doris A, Ebmeier K, Shajahan P. Depressive illness.Lancet. 1999; 354(9187): 1369-1375. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03121-9

2. Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ.Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors,2001: systematic analysis of population health data.Lancet. 2006; 367(9524): 1747-1757. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9

3. Brown P. The global burden of disease. A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020.Summary. Boston Massachusetts Harvard University School of Public Health. 1990; 3(9): 1308-1314

4. Rush AJ, Thase ME, Dube S. Research issues in the study of difficult-to-treat depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(8): 743-753. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00088-X

5. Can OD, Osmaniye D, Demir Ozkay U, Saglik BN, Levent S, Ilgin S, et al. MAO enzymes inhibitory activity of new benzimidazole derivatives including hydrazone and propargyl side chains. Eur J Med Chem. 2017; 131: 92-106.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.03.009

6. Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A. Technology insight: noninvasive brain stimulation in neurology-perspectives on the therapeutic potential of rTMS and tDCS. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007; 3(7): 383-393.doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncpneuro0530

7. Morellini N, Grehl S, Tang A, Rodger J, Mariani J, Lohof AM,Sherrard RM. What does low-inten 10.1002/hbm.22339 sity rTMS do to the cerebellum? Cerebellum. 2015; 14(1):23-26.doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12311-014-0617-9

8. Julian JB, Ryan J, Hamilton RH, Epstein RA. The Occipital Place Area Is Causally Involved in Representing Environmental Boundaries during Navigation. Curr Biol.2016; 26(8): 1104-1109. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.02.066

9. Ahdab R, Ayache SS, Brugieres P, Farhat WH, Lefaucheur JP.The Hand Motor Hotspot is not Always Located in the Hand Knob: A Neuronavigated Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Study. Brain Topogr. 2016; 29(4): 590-597. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10548-016-0486-2

10. Ahdab R, Ayache SS, Farhat WH, Mylius V, Schmidt S,Brugieres P, Lefaucheur JP. Reappraisal of the anatomical landmarks of motor and premotor cortical regions for image-guided brain navigation in TMS practice. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014; 35(5): 2435-47. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22339

11. Paz Y, Friedwald K, Levkovitz Y, Zangen A, Alyagon U,Nitzan U, et al. Randomised sham-controlled study of highfrequency bilateral deep transcranial magnetic stimulation(dTMS) to treat adult attention hyperactive disorder(ADHD): Negative results. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2017;2017: 1-6.doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15622975.2017.1282170

12. Levkovitz Y, Isserles M, Padberg F, Lisanby SH, Bystritsky A, Xia G, et al. Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depression: a prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial. World Psychiatry.2015; 14(1): 64-73.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/wps.20199

13. Zhang J, Cui M, Wu Y, Song H, Zhai C, Deng J, et al. [The effect of low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with duloxetine in treatment of depression]. Zhongguo Shen Jing Jing Shen Ji Bing Za Zhi.2015; 41(5): 288-292. Chinese

14. Aguirre I, Carretero B, Ibarra O, Kuhalainen J, Martinez J,Ferrer A, et al. Age predicts low-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation efficacy in major depression. J Affect Disord. 2011; 130(3): 466-469. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.038

15. Organization WH. The ICD-10 Classif i cation of Mental and Behavioural Disorders-Diagnostic Criteria for Research.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993

16. Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.4th ed. Washington DC: APA; 1994

17. Chinese Medical Association Psychiatry Branch. China Classif i cation and Diagnostic Criteria of Mental Disorders,3rdEdition (Mental Disorders); 2001

18. Fang M, Reng YP, Liu H, Zhou F, Wang G. [The treatment of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with Pa Rossi Dean on major depressive disorder]. Shou Du Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2014; 35(2): 194-199. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1006-7795.2014.02.011

19. Ray S, Nizamie SH, Akhtar S, Praharaj SK, Mishra BR, Zia-Ul-Haq M. Efficacy of adjunctive high frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of lef prefrontal cortex in depression: A randomized sham controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2014; 156: 247-247. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.027

20. Zhang YM. [The control study of low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of depression (thesis)]. Nanchang: Medical College of Nanchang University; 2010. Chinese

21. Fang M. [A randomized double-blind control study of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with Pa Rossi Dean in the treatment of major depressive disorder (thesis)]. Beijing: Capital Medical University; 2008.Chinese

22. Concerto C, Lanza G, Cantone M, Ferri R, Pennisi G, Bella R, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with drug-resistant major depression: A six-month clinical follow-up study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2015;19(4): 253-259. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/13651501.2 015.1084329

23. George MS, Wassermann EM, Kimbrell TA, Little JT, Williams WE, Danielson AL, et al. Mood improvement following daily lef prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with depression: A placebo-controlled crossover trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1997; 154(12): 1752-1756. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/ajp.154.12.1752

24. Klein E, Kreinin I, Chistyakov A, Koren D, Mecz L, Marmur S,et al. Therapeutic efficacy of right prefrontal slow repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in major depression:a double-blind controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry.1999; 56(4): 315-320. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.71.4.546

25. Berman RM, Narasimhan M, Sanacora G, Miano AP,Hoffman RE, Hu XS, et al. A randomized clinical trial of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47(4): 332-337. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00243-7

26. George MS, Nahas Z, Molloy M, Speer AM, Oliver NC, Li XB, et al. A controlled trial of daily left prefrontal cortex TMS for treating depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(10): 962-970. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01048-9

27. Garcia-Toro M, Pascual-Leone A, Romera M, González A,Micó J, Ibarra O, et al. Prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as add on treatment in depression.J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001; 71(4): 546-548. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.71.4.546

28. Kauffmann CD, Cheema MA, Miller BE. Slow right prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation as a treatment for medication-resistant depression: A double-blind,placebo-controlled study. Depress Anxiety. 2004; 19(1): 59-62. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/da.10144

29. Rumi DO, Gattaz WF, Rigonatti SP, Rosa MA, Fregni F, Rosa MO, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation accelerates the antidepressant effect of amitriptyline in severe depression: A double-blind placebo-controlled study.Biol Psychiatry. 2005; 57(2): 162-166. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.029

30. Avery DH, Holtzheimer PE, Fawaz W, Russo J, Neumaier J, Dunner DL, et al. A controlled study of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in medication-resistant major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2006; 59(2): 187-194.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.003

31. Januel D, Dumortier G, Verdon CM, Stamatiadis L, Saba G, Cabaret W, et al. A double-blind sham controlled study of right prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): Therapeutic and cognitive effect in medication free unipolar depression during 4 weeks. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006; 30(1): 126-130.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.016

32. Loo C K, Mitchell PB, Mcfarquhar TF, Malhi GS, Sachdev PS. Sham-controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of twice-daily rTMS in major depression. Psychol Med.2007; 37(3): 341-349. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291706009597

33. O’reardon JP, Solvason HB, Janicak PG, Sampson S, Isenberg KE, Nahas Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: A multisite randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2007; 62(11): 1208-1216. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.018

34. Mogg A, Pluck G, Eranti SV, Landau S, Purvis R, Brown RG,et al. A randomized controlled trial with 4-month follow-up of adjunctive repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the left prefrontal cortex for depression. Psychol Med.2008; 38(3): 323-333. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707001663

35. Schutter DJ, Laman DM, Van Honk J, Vergouwen AC,Koerselman GF. Partial clinical response to 2 weeks of 2 Hz repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to the right parietal cortex in depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol.2009; 12(5): 643-650. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1461145708009553

36. George MS, Lisanby SH, Avery D, Mcdonald WM, Durkalski V, Pavlicova M, et al. Daily left prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy for major depressive disorder: A sham-controlled randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010; 67(5): 507-516. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.46

37. Lingeswaran A. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in the Treatment of depression: A Randomized,Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Trial. Indian J Psychol Med. 2011; 33(1): 35-44. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.85393

38. Ray S, Nizamie SH, Akhtar S, Praharaj SK, Mishra BR, Zia-Ul-Haq M, et al. Efficacy of adjunctive high frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of left prefrontal cortex in depression: A randomized sham controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2011; 128(12): 153-159.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.027

39. Zhang XH, Wang LW, Wang JJ, Liu Q, Fan Y. [Adjunctive treatment with transcranial magnetic stimulation in treatment resistant depression:a randomized,doubleblind,sham-controlled study]. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry.2011; 23(1): 17-24. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2011.01.005

40. Huang ML, Luo BY, Hu JB, Wang SS, Zhou WH, Wei N, et al.Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in combination with citalopram in young patients with fi rst-episode major depressive disorder: a double-blind, randomized, shamcontrolled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012; 46(3): 257-64.doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0004867411433216

41. Wang Z, Wang HN, Chen YC, Wang HH, Zhang YH, Xi M,et al. [High frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as adjuvant treatment of venlafaxine in the treatment of depression]. Lin Chuang Jing Shen Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2012; 22(3): 188-190. Chinese

42. Li J, Lin WC, Liang L, Wang HK. [Clinical Study on rTMS and Mirtazapine in the Treatment of Treatment-Resistant Depression]. Lin Chuang Yi Xue Gong Cheng. 2013; 20(7):785-786. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1674-4659.2013.07.0785

43. Wang LN, Pan F, Li YF. [Effects of low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on treatment-resistant depression and cognitive function]. Zhongguo Kang Fu Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2013; 28(6): 544-548. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1001-1242.2013.06.012

44. Qi GC. [Efficacy of high frequency rTMS combined with duloxetine in the treatment of depression]. Jing Shen Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2014; 27(6): 455-457. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1009-7201.2014.06.019

45. Xu ZP, Tang LY, Deng LH, Song ZW. [Inf l uences of fl uoxetine plus rTMS on efficacy and cognitive function of depression patient]. Lin Chuang Xin Shen Ji Bing Za Zhi. 2014; 20(4):82-84. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1672-187X.2014.04.030-0082-04

46. Xie M, Jiang W, Yang H. Efficacy and safety of the Chinese herbal medicine shuganjieyu with and without adjunctive repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS)for geriatric depression: a randomized controlled trial.Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2015; 27(2): 103-110. doi:http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.214151

47. Hu YL, Wu SY. [Influences of escitalopram plus repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on the therapeutic effect and cognitive function of fi rst-episode depression patients].Lin Chuang Xin Shen Ji Bing Za Zhi. 2015; 21(6): 78-80.Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1672-187X.2015.06.026-0078-03

48. Shi YM, Xu XM, Sun HJ, Jin HQ, Hao CJ. [Clinical Study on rTMS and duloxetine in the Treatment of Treatment-Resistant Depression]. Xian Dai Yang Sheng. 2015; 9:57-59. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1671-0223.2015.09.044

49. Xiao CX, Zhong WW, Nuerbiya MMTM, Chen JY.[Clinical Effect of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation on Mild to Moderate Depressive Disorder].Shi Yong Xin Nao Fei Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2015; 10:69-71. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1008-5971.2015.10.018

50. Liang WF, Xiao XM, Mo ZC, Jiang LD. [Effect of rTMS Assisted With Agomelatine on HAMD Score, Quality of Life and Adverse Reactions of Adult Patients With First-episode Depression]. Neimenggu Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2016; 48(8): 897-900. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.16096/J.cnki.nmgyxzz.2016.48.08.001

- 上海精神医学的其它文章

- Comparisons of Superiority, Non-inferiority, and Equivalence Trials

- Analysis of Family Functioning and Parent-Child Relationship between Adolescents with Depression and their Parents

- CHN2 Promoter Methylation Change May Be Associated With Methamphetamine Dependence

- The Relationship between the Lifestyle of the Elderly in Shanghai Communities and Mild Cognitive Impairment

- Status Investigation of Outpatients Receiving Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT) in Shanghai from 2005 to 2016

- Senile Depression with Somatization Symptoms and Insomnia is Diagnosed as Multiple System Atrophy: A Case Report