哲学仅仅是比科学难懂吗?

By+David+Papineau

W hats the purpose of philosophy? Alfred North Whitehead characterized it as a series of footnotes to Plato.1 You can see his point. On the surface, we dont seem to have progressed much in the two and a half millennia since Plato wrote his dialogues. Todays philosophers still struggle with many of the same issues that exercised the Greeks. What is the basis of morality? How can we define knowledge? Is there a deeper reality behind the world of appearances?

Philosophy compares badly with science on this score. Since science took its modern form in the 17th century, it has been one long success story. It has uncovered the workings of nature and brought untold benefits to humanity. Mechanics and electromagnetism underpin the technological advances of the modern world, while chemistry and microbiology have done much to free us from the tyranny of disease.2

Not all philosophers are troubled by this contrast. For some, the worth of philosophy lies in the process, not the product. In line with Socrates dictum—“The unexamined life is not worth living”—they hold that reflection on the human predicament is valuable in itself,3 even if no definite answers are forthcoming. Others take their lead from Marx—“The philosophers have only interpreted the world. The point, however is to change it”—and view philosophy as an engine of political change, whose purpose is not to reflect reality, but disrupt it.

Even so, the majority of contemporary philosophers, myself included, probably still think of philosophy as a route to the truth.

According to the “spin-off” theory of philosophical progress, all new sciences start as branches of philosophy, and only become established as separate disciplines once philosophy has bequeathed them the intellectual wherewithal to survive on their own.4

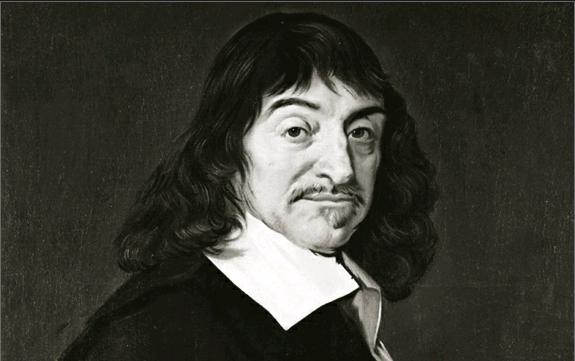

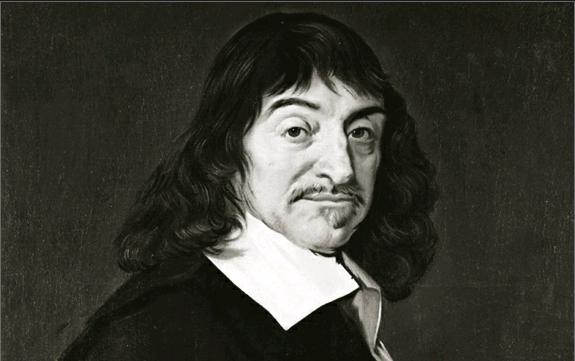

There is certainly something to this story. Physics as we know it was grounded in the 17th-century “mechanical philosophy” of Descartes5 and others. Similarly, much psychology hinges on associationist principles first laid down by David Hume, and economics grew out of doctrines first developed by thinkers who called themselves philosophers.6 The process continues into the contemporary world. During the 20th century, both linguistics and computer science broke free of their philosophical moorings7 to establish themselves as independent disciplines.

According to the spin-off theory, then, the supposed lack of progress in philosophy is an illusion. Whenever philosophy does make progress, it spawns a new subject, which then no longer counts as part of philosophy. In reality, philosophy is full of progress, but this is obscured by the constant renaming of its intellectual progeny8.endprint

What about those areas where we still seem to be struggling with the same issues as the Greeks? Philosophy hasnt outsourced everything to other university departments, and still retains plenty of its own questions to exercise its students. The trouble is that it doesnt seem to have any definite answers. When it comes to topics like morality, knowledge, free will, consciousness and so on, the lecturers still debate a range of options that have been around for a long time.

No doubt some of the differences between philosophy and science stem from the different methods of investigation that they employ. Where philosophy hinges on analysis and argument, science is devoted to data.

Given this contrast, it is scarcely surprising that philosophers disagree more than scientists. Data are data. If you are shown some experimental findings, well, there you are. But arguments have loopholes. So there is always plenty of room for philosophers to take issue with each other, where scientists by contrast have to accept what they are told.

Questions of physics and chemistry can always be settled by experimental investigation, whereas empirical methods get no grip on morality and free will.9 The problem is that, even though we have all the experimental results we could want, we cant figure out a coherent theory to accommodate them.10 Philosophical problems arise within science as well as outside it.

Philosophical issues typically have the form of a paradox11. People can be influenced by morality, for example, but moral facts are not part of the causal order. Free will is incompatible with determinism,12 but incompatible with randomness too. We know that we are sitting at a real table, but our evidence doesnt exclude us sitting in a Matrix-like13 computer simulation. In the face of such conundrums, we need philosophical methods to unravel our thinking.14 Something is amiss, but we arent sure what. We need to catalogue our assumptions, often including those we didnt know we had, and subject them to15 critical analysis.

This is why philosophical problems can arise in scientific subject areas too. Scientific theories can themselves be infected by paradox. Altruism16 cant possibly evolve, but it does. Here again philosophical methods are called for. We need to figure out where our thinking is leading us astray, to winnow through our theoretical presuppositions and locate the flaws.17endprint

It should be said that scientists arent very good at this kind of thing. They are much happier with what Thomas Kuhn called “normal science”, working within “paradigms”of settled assumptions and techniques that allow them to focus on issues that can be settled experimentally.18 When they are faced with a real theoretical puzzle, most scientists close their eyes and hope it will go away.

Perhaps there is more progress in philosophy than at first appears, even apart from the spin-off disciplines. On the surface it may look as if nothing is ever settled. But behind the appearances, philosophy is by no means incapable of advancing.

哲學的目的是什么?阿尔弗雷德·诺斯·怀特海德认为,哲学无非是柏拉图哲学的注脚。你能明白他的意思。表面上看,在柏拉图《对话录》之后的2,500年里,哲学并没有取得多大进步。千年前困扰希腊哲人的问题如今依旧让哲学家感到头疼。比如:道德的基础是什么?如何定义知识?世间万物的表象下是否深藏着一个真相?

在这一点来说,哲学比科学差了不少。自17世纪起,现代意义上的科学就已成形,并开始书写它漫长的成功史。科学揭示了自然的运作方式,为人类带来无尽的福祉。机械和电磁学推进了现代社会的科技进步,化学和微生物学让我们免受疾病的暴力侵袭。

并非所有哲学家都为这一悬殊对比而烦恼。一些哲学家认为,哲学的价值在于探索的过程,而非结果。古希腊哲学家苏格拉底有句名言:“未经审视的人生不值得过”,赞同苏格拉底的这些哲学家认为对人类困境的思索本身就是可贵的,即便这样的思索得不出确切的答案。还有一些哲学家以马克思的名言为导向——“哲学家只是解释世界,而问题在于改变世界”,认为哲学是政治变革的引擎,其目的并非反映现实,而是干预现实。

即便如此,大多数当代哲学家,包括我在内,仍然认为哲学是通往真理之径。

根据哲学发展的“副产品”理论,所有新兴科学一开始都是哲学的分支,只有哲学赐予它们足够的知识能力后才能靠自己生存,成为一门独立学科。

这么说当然不是空穴来风。我们所熟知的物理学是基于17世纪笛卡尔和其他哲学家的“机械论哲学”。同样,当代心理学的许多理论都是依靠大卫·休谟最早提出的联想原则,经济学也是从自称为哲学家的思想家们所研究出的规则中发展出来的。这一进程持续到当今社会。20世纪,语言学和计算机科学也脱离哲学范畴,成为了独立学科。

根据“副产品”理论,哲学领域看似发展缓慢其实只是一个幻觉。哲学的每一次进步都孵化出一门新学科,随即脱离哲学而独立存在。其实,哲学一直在前进,只是它的进步被其知识成果经常性的重命名所掩盖了。

那么,那些曾经困扰希腊哲人,现在仍然在困扰我们的领域呢?哲学并没有把所有问题都转嫁给大学其他院系,而是保留了许多问题让哲学系学生来开动脑筋。问题是对于这些问题,哲学上并没有明确的答案。在谈到道德、知识、自由意志、意识等话题时,讲师们争论的仍然是由来已久的内容。

毫无疑问,哲学和科学之间的一些差异源于它们探索问题时采取的不同方法。哲学强调分析和论证,科学看重数据。

考虑到这一对比,哲学家比科学家更容易彼此产生分歧就不足为奇了。科学靠数据说话。如果你有实验数据,好吧,听你的。但是论证会有漏洞。因此,哲学家有足够的空间来互相质疑,而相比之下,科学家则只能接受实验数据。

物理和化学问题总能用实验研究解决,然而经验主义的方法对道德和自由意志却行不通。因为尽管我们有一切想要的实验结果,却找不到一个通俗的理论来解释它。哲学问题产生于科学之内,也产生于科学之外。

哲学问题通常以悖论的形式存在。比如,人们会被道德所影响,但是道德事实却不遵循因果顺序。自由意志与宿命论不兼容,但与随机性也不兼容。我们知道自己坐在一张真实的桌子旁,但我们的数据并不排除自己其实是坐在一个像《黑客帝国》里那样的虚拟世界中。面对这样的难题,我们需要哲学方法来揭开思维之谜。我们总觉得哪里出了问题,却又不敢肯定。所以,我们需要为假想归类,通常包括那些我们并不知其存在的东西,然后对它们进行批判性分析。

这就是为什么哲学问题也会出现在科学领域。科学理论本身会被悖论影响。利他主义本不可能发展,而实际上却发展了。因此这里需要再次诉诸哲学方法。我们要找出思维在何处偏离了轨道,剔除理论假想,找到问题所在。

需要指出的是科学家并不擅长这类事情。科学家更乐意研究托马斯·库恩所说的“常规科学”,在既定设想和方法的“范式”内工作,以便集中研究可以用实验来解决的问题。当科学家面临真正的理论难题时,绝大多数人会闭上眼睛,祈祷问题自行消失。

或许哲学的进步比最初看起来的要大,即使不算它的“副产品”学科。表面上看,哲学似乎什么问题也没有解决。但在表象之下,哲学绝不是无力前进的。endprint

1. Alfred North Whitehead: 阿尔弗雷德·诺斯·怀特海德(1861—1947),英国数学家、哲学家,“过程哲学”的创始人;Plato: 柏拉图(427BC—347BC),古希腊伟大的哲学家,也是整个西方文化最伟大的哲学家和思想家之一。他和老师苏格拉底、学生亚里士多德并称“希腊三贤”。

2. underpin: 加强,巩固;tyranny: 暴虐,专横。

3. dictum: 名言,格言;predicament:// 困境,窘况。

4. spin-off: 副产品;bequeath: 遗赠,遗留;wherewithal: //(某一特定用途的)必要资金,必要手段。

5. Descartes: 勒内·笛卡尔(Rene Descartes, 1596—1650),法国著名哲学家、物理学家、数学家,有“近代哲学之父”、“解析几何之父”之称。

6. hinge on: 依……而定,取决于;David Hume: 大卫·休谟(1711—1776),苏格兰哲学家,是苏格兰启蒙运动以及西方哲学史中的重要人物;doctrine:教条,学说。

7. mooring: (绳、链等)系船用具,系泊装置。

8. progeny: // 后代,后续事物。

9. empirical: 以科学实验为依据的,经验主义的;get a grip on: 理解,掌握。

10. coherent: (陈述)条理清楚的,易于理解的;accommodate: 使适应,使相符。

11. paradox: 悖论,自相矛盾的人或事。

12. incompatible: 不相容的,矛盾的;determinism: 决定论,宿命论。

13. Matrix: 指电影《黑客帝国》里的虚拟世界“矩阵”(The Matrix)。影片中人类生活在这个完全沉浸式的虚拟现实中,并认为这就是真实世界。

14. conundrum: // 令人迷惑的难题,复杂难解的问题;unravel: 阐释,说明。

15. subject to: 使经受,使遭受。

16. altruism: 利他主义,指无私地为他人的福利着想、认为别人的幸福快乐比自己的更重要的行为。

17. lead sb. astray: 把某人引入歧途;winnow:筛选,遴选;presupposition: 预先假定(的事)。

18. Thomas Kuhn: 托马斯·库恩(1922—1996),美国科学史家、科学哲学家,代表作有《哥白尼革命》和《科学革命的结构》;paradigm: // 范式。

阅读感评

∷秋叶 评

原文中讨论的哲学与科学的关系,令笔者联想到大约60年前英国物理化学家兼小说家C. P. 斯诺提出的“两种文化”的概念,用以描绘他所见的科学与文学之间的分野。1959年5月,斯诺在剑桥作了一个讲座,题目是《两种文化与科学革命》,后来又据此出版了同名书籍。斯诺的著名论断是“所有西方社会的知识生活都日益分裂成两个处于顶端的团体”,即科学家与文学研究者。斯诺大致将当时的“相互之间无法理解的鸿沟”归咎于研究文学的那一类人。他断言,这些知识分子对于自己不懂热力学第二定律一点都不感觉害臊尴尬。然而问一位科学家“你读过莎士比亚的作品吗”,显然会让他大失颜面。斯诺认为社会科学家们能够形成“第三种文化”。大约三十多年前,美国出版代理人约翰·布罗克曼套用“第三种文化”的概念来描绘进化生物学家、心理学家与神经学家,因为在他看来,这些以人为主要研究对象的科学家“向我们呈现了生活的深层意义”,并在“塑造他们那一代思想”的能力方面超越了文学艺术家们。诚然,至少在西方,自16世纪开始的科学革命呈现了持续不断、日积月累的发展历程。也是自那时起,科学在西方逐渐成为了占支配地位的知识实践,同时以人们未曾预见的方式改变这个世界,并解决人类的一系列问题。与此相对,斯诺认为,20世纪的进步正在受到来自诗人与小说家漠然态度的阻碍。英国数学家、哲学家怀特海德(Alfred N. Whitehead)更是把古希腊以后的哲学研究说成只是“给柏拉图做注脚(a series of footnotes to Plato)”,似乎这25个世纪的哲学研究都无法跨越其《对话录》的高峰,这与现代意义上科学发展不断获得重大发现与发明的一般规律形成了鲜明的对比。

然而,我们知道,虽然科学与哲学追求的都是真理,但两者在追求真理之路上的侧重点与所采用的方式方法并不完全相同,常有物质与精神及客观世界与主观世界的分野。因此,它们之间实在难以作机械的比较,更无法“一决高下”。“哲学”在人类社會中自有其价值与贡献,更是人类不可或缺的知识与传统。在古希腊语中,“philosophia”是“爱智慧(love of wisdom)”的意思。在英国历史上写下浓墨重彩一笔的阿尔弗雷德大帝(Alfred the Great, 849—899)曾亲手制订了一个教育普通人和神职人员的读书计划,因为他认为“没有比智慧更重要的东西了”。

哲学有自己永恒的主题,如原文中提到的“道德的基础”、“知识的定义”、“自由意志与理念”,以及“表象与真相的关系”等等。其实,这些正是欧洲文艺复兴时期所标举的“人文主义”的核心内容,也正是18世纪英国诗人亚历山大·蒲柏(Alexander Pope)所想的“对人类彻底的研究是对人本身的研究”。自柏拉图以来直至当代哲学家福柯与德里达,不断地对上述问题予以叩问与阐释,但迄今为止似乎并未达成什么共识,更看不到哲学统一的前景。科学的倾向和形而上学的倾向并存,存在主义的主观性与实证主义的客观性互不相让,众说纷纭、各立门户是哲学领域中的普遍现象。科学的推进靠实验与数据的客观标准与实证规范,而哲学却是由大脑的“智慧”决定,靠个人的阐释、分析甚至偏爱,在因果关系与逻辑上都难以做到无懈可击,自然也就允许见仁见智了。其实人文学术的特点概莫如此。好在人文学术的推进,并不像政治外交那样,常需要“思想统一”或达成“共识”作为问题解决的基础。原文说“哲学的价值在于过程,而非结果”,“思考本身比确切的答案更有价值”,此言不谬。

有人说,文学让人浪漫,历史让人厚重,哲学让人深刻。如果从另一角度来看,我们会发现,文学乃人生百态的临摹与再现,是对人情感的训练;历史因其提供的大图景与纵深视角,是对睿智生活的训练,而哲学即为对人理性思维的训练。这三种训练所造就的能力相得益彰,使得人生更有价值。我们必须承认,在很大程度上由于科学的发展,20世纪给大约一半的人类带来了前所未有的物质繁荣,但遗憾的是,随之而来的并非是与其相应的社会的更加安全和稳定。笔者相信,人文学科可以对整个人类的繁荣与幸福作出贡献,因为“精神”层面的关注会使生活更有价值。但同时也需指出,倘若缺乏理性思维与分析深度,人类会付出沉重代价,因为倘若“理性沉睡,群魔乱舞”!endprint