气候变化背景下野生动物脆弱性评估方法研究进展

李 佳, 刘 芳, 张 宇, 薛亚东, 李迪强

中国林业科学研究院森林生态环境与保护研究所,国家林业局森林生态环境重点实验室,北京 100091

气候变化背景下野生动物脆弱性评估方法研究进展

李 佳, 刘 芳, 张 宇, 薛亚东, 李迪强*

中国林业科学研究院森林生态环境与保护研究所,国家林业局森林生态环境重点实验室,北京 100091

脆弱性评估是研究气候变化影响野生动物的重要内容,识别野生动物脆弱性,是适应和减缓气候变化影响的关键和基础。开展气候变化背景下野生动物的脆弱性评估工作,目的是为了确定易受气候变化影响的物种和明确导致物种脆弱性的因素,其评估结果有助于人类认识气候变化对野生动物的影响,为野生动物适应气候变化保护对策的制定提供科学依据。对野生动物而言(物种),脆弱性是物种受气候变化影响的程度,包括暴露度、敏感性和适应能力三大要素。其中,暴露度是由气候变化引起的外在因素,如温度、降雨量、极值天气等;敏感性是受物种自身因素影响,如种间关系、耐受性等;适应能力是物种通过自身调整来减小气候变化带来的影响,如迁移或扩散到适宜生境的能力、塑性反应和进化反应等。对近期有关气候变化背景下野生动物脆弱性评估方法予以综述,比较每种评估方法所选取指标的差异,总结在脆弱性评估中遇到的不确定性指标的处理方法,以及脆弱性评估结果在野生动物适应气候变化对策中的应用。通过总结野生动物脆弱性评估方法,以期为气候变化背景下评估我国野生动物资源的脆弱性提供参考方法。

气候变化;脆弱性;暴露度;敏感性;适应性保护对策

气候变化是国际社会普遍关注的重大全球环境问题,联合国政府间气候变化专门委员会(IPCC)第5次评估报告指出,全球气候变暖这一不可否认的事实,人类活动是导致近百年来全球普遍增温的主要原因,在过去的100多年间(1880—2012年),气温上升了约0.85℃,尤其是近60多年,气温升高了0.72℃[1]。人类活动所引起的温室气体增加以及由此造成的全球气候变暖和对全球生物多样性的影响越来越引起人们的关注[2- 3]。

全球气候变暖对生物多样性产生了很大的影响。大量观测事实表明,气候变暖对物种地理分布[4- 5]、种群动态[6- 7]、物候特征(包括产卵期、迁徙期、迁徙距离等)[8- 9]、进化[10- 11]等方面产生深刻影响,且这些影响在未来将会变得更加剧烈[12- 13]。如果气候变暖的趋势得不到有效的遏制,温度升高2℃(升高2℃被联合国气候变化公约组织(UFCCC)定义为“危险”温度[14]),全球将有15%─35%物种灭绝[15],这无疑将会给生物多样性的保护带来严峻挑战。尽管气候变化对生物灭绝程度和速度的预测存在一定的争议,但气候变暖加速生物灭绝的现状和趋势已经被广泛证实[16- 17]。目前,在全球气候变化背景下,如何制定有效的生物多样性保护对策,已成为政府、生态学家和民众普遍关注的热点问题。

脆弱性评估是研究气候变化影响野生动物的重要内容,识别野生动物脆弱性,是适应和减缓气候变化影响的关键和基础,国际上IPCC、国际自然保护联盟(IUCN)等相关组织以及美国、欧盟等国家正在开展这方面的研究,通过开展气候变化背景下野生动物的脆弱性评估工作,提出建立野生动物适应气候变化的科学对策,最终为人类能有效应对气候变化和野生动物保护提供强有力的依据[3,18- 21]。在我国,气候变化背景下野生动物脆弱性评估工作,已被《生物多样性保护战略与行动计划(2011—2030年)》列为未来20年优先行动计划[22]。然而,目前该领域研究还处于探讨、介绍的层面,评估方法认识还不足[23]。为此,本文对近期国外有关气候变化背景下野生动物脆弱性评估方法予以综述,以期为气候变化背景下评估我国野生动物资源的脆弱性提供方法参考。

1 脆弱性的概念

IPCC对脆弱性进行了较为完整的定义,认为脆弱性是指系统易于遭受或没有能力去应对气候变化引起的负面影响的程度,包括系统暴露度、敏感性和适应能力三大要素[24]。暴露度是系统遭受气候变化胁迫的程度,敏感性是系统被气候变化胁迫改变的程度,适应能力是系统通过调整来适应气候变化的能力。通常来讲暴露度和敏感度的增大,会加剧系统的脆弱性;适应能力的增强则会降低系统的脆弱性[25]。对野生动物而言(物种),脆弱性是物种受气候变化影响的程度,同样包括暴露度、敏感性和适应能力三大要素[26- 27]。敏感性是受物种自身因素影响,如生态学、生理学、生活史、行为、基因多样性、种间关系等[28- 29];暴露度是由气候变化引起的外在因素,如温度、降雨量、极值天气等直接影响因素,以及气候变化改变物种栖息环境、植被结构和组成、海平面上升等间接影响因素[29- 31];适应能力是物种通过自身调整来减小气候变化带来的影响,如迁移或扩散到适宜生境的能力、塑性反应和进化反应等[32- 33]。

2 脆弱性评估的意义

评估物种脆弱性,是为其制定有效的气候变化适应对策提供科学依据[30]。脆弱性评估主要解决两个问题:(1)确定易受气候变化影响的物种;(2)明确导致物种脆弱性的因素[28]。脆弱性评估有利于科研人员和管理决策者理解气候变化的影响,了解物种脆弱性分布、脆弱性成因,同时制定相应的适应性保护策略,从而增强物种的适应能力。因此,脆弱性评估工作被认为是一切适应气候变化对策制定的开始[30]。

3 脆弱性评估方法

目前,气候变化背景下野生动物脆性评估是一个比较新的研究领域,评估方法不多,现有文献中有关气候变化的野生动物脆弱性评估方法归纳为三类,生物气候包络模型评估、机理性生态位模型和脆弱性指数评估[27,30,34]。

3.1 生物气候包络模型评估

基于空间生态位理论发展起来的生物气候包络模型(Bioclimate envelope)是评估物种脆弱性的方法之一,通过模型能获得较准确的物种分布范围,并能预测未来物种分布的变化[35- 38]。物种是否脆弱性主要通过对比物种现今潜在分布区和未来预测分布区的变化,如果物种未来预测分布区大范围缩减,或者未来分布区与当前潜在分布区重叠较少,则表明气候变化对物种影响较大[39- 41]。Lawler等利用模型预测气候变化对2954种脊椎动物的影响,结果表明至少有10%的物种将会消失,且90%的物种分布区系将会发生变化[42];Sinervo等预测,到2080年气候变化将会导致墨西哥20%的蜥蜴种类灭绝[43];Pearson等利用模型分析气候变化对36种美国特有两栖类和爬行类的影响,在不考虑气候变化情景下,到2100年,只有少于1%的物种将会灭绝,而考虑CO2排放较高情景下,将有28%的物种会灭绝[44];生活在海洋中的生物同样面临着气候变化的影响,Poloczanska等对全球1735种洋海生物进行研究,发现81%—83%的物种分布、物候、群落组成、丰富度等发生显著变化[45]。类似结果如澳大利亚的树袋熊(Phascolarctoscinereus)[46]、太平洋海象(Odobenusrosmarusdivergens)[47]、喜马拉雅山的雪豹(Pantherauncia)[48]、中国的大熊猫(Ailuropodamelanoleuca)[37,49- 50],气候变化可能导致这些物种未来适宜栖息地面积大量缩减,加快物种灭绝的速度。当然,气候变化并非总是导致物种栖息地减少,有些物种可能得益于气候变暖,导致其种群扩散,如华夏粗针蚁(Pachycondylachinensis)[51]、美国的牛蛙(Ranacatesbeiana)[52]、欧洲的葛氏鲈塘鳢(Perccottusglenii)[53]等物种,预测有可能在全球或局域扩散的趋势。模型能准确预测物种分布范围,然而简单利用模型预测物种未来分布变化来评估物种脆弱性,这种评估方法有其不足和局限性[40,54]。模型主要考虑气候因素,经常会忽略掉一些重要的生物或非生物因素,如物种对环境因素的耐受性、物种间相互作用、迁移和进化能力、地理异质性等,这无疑将会影响模型的预测能力[40]。

3.2 机理性生态位模型评估

基于物种野外观察(如种群动态、迁移等)和实验(如生理耐受性)发展而来的模型,如种群生存力分析、生理耐受阈值和迁移模型等,总称为机理性生态位模型,同样被用于评估物种脆弱性[27,30,55]。机理性生态位模型主要通过分析未来气候变化背景下物种灭绝的概率、物种对各因子的生理耐受范围、物种是否迁移、土地利用变化等信息,来评物种脆弱程度[27]。Naveda-Rodríguez等结合物种分布模型和漩涡模型(Vortex model)分析安第斯秃鹰(Culturgryphus)种群灭绝风险,认为生境丧失是该物种面临的最大威胁[56];Jenouvrier等认为气温变暖将会是导致栖息在南极洲帝企鹅(Aptenodytesforesteri)种群生存力下降[57]。基于生理耐受性的脆弱性评估方法认为动物对环境因子的生理耐受范围限制了物种的分布[58],如大部分变温动物主要分布在低洼热带雨林[59]、栖息在海洋中的变温动物将向极地和赤道扩张分布[60],而一些地方特有或岛屿昆虫类限制在海拔较低的区域[61];Schloss等利用物种迁移能力来评估气候变化背景下西半球兽类脆弱性,认为气候变化速率超出许多兽类迁移速率,西半球将会有39%的兽类无法通过自身扩散来适应气候变化[62]。机理性生态位模型要求对各物种的基本信息非常准确,如生理耐受范围、物种迁移能力、种群动态、种群结构等,而这些信息往往不易确定,需要开展大量的研究工作[27,63]。

3.3 脆弱性指数评估

自杀是一种复杂的社会现象,研究者可以从多个方面来理解和考察。在进化心理学的框架下,de Catanzaro(1991)提出的适应器理论激发了众多的研究,值得感兴趣的研究者予以关注。不过,这一理论依然还需要更多研究的检验,而感兴趣的研究者可以在未来着重考虑以下几个方面。

脆弱性指数利用物种敏感性、暴露度和适应能力等指标,通过给每个指标打分来评估物种脆弱度,是目前全球气候变化背景下野生动物脆弱性评估使用最普遍的方法[30]。脆弱性指数需整合大量的物种信息,如物种分布、种群动态、生活史、生理、以及模型预测等[55,64]。大量信息可以通过已发表文献、文学报道、实验、野外观察、以及从网站下载气候数据等途径获取[30,55,65]。为简化这些工作,许多研究人员和机构开发了一些框架或系统来更有效的评估物种脆弱性。

3.3.1 CCVI指数

CCVI指数(Climate Change Vulnerability Index, CCVI)由美国自然保护组织-自然服务开发,自然服务建立了北美生物多样性数据平台,并开发了基于该数据库的脆弱性指数评估,旨在用来评估未来50年内气候变化背景下北美地区物种脆弱性,是目前脆弱性评估中使用最多的一种方法[54,64,66]。CCVI指数由以下4部分组成:(1)预测评估区域在未来气候变化下的直接暴露度(如温度升高、湿度变化等指标);(2)预测评估区域由气候变引起的间接暴露度(如海平面上升);(3)物种敏感性因素(如生理耐受幅度、种间关系等指标);(4)物种对气候变化的适应(模型预测未来适宜生境变化等指标)。Tuberville等利用CCVI指数评估气候变化对美国东南部沙丘生态区域117种两栖和爬行类动物的影响,结果表明该区域46.2%的物种将变得中等脆弱级别以上,只有14.5%的物种保持稳定[34];类似结果如栖息在加州内华达山脉168种鸟类中有16个物种将变得中等脆弱,1个物种极度脆弱,生活在高山或水栖鸟类比其它生境中的鸟类更容易受到气候变化的影响[67];兽类如美洲狮(Pumaconcolor)不脆弱、凯鹿(Odocoileusvirginianusclavium)比较脆弱、冈比亚巨囊鼠(Cricetomysgambianus)中等脆弱[68]。目前,CCVI指数并没有被广泛应用于脆弱性评估,主要原因在于该指数在研发时许多指标(如暴露度等指数),主要针对栖息在北美地区的物种,研究区域受到限制,然而该指数提供了非常全面的评估指标,值得其他地区在评估物种脆弱性时借鉴。

3.3.2 CCVA评估框架

CCVA评估框架(Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment, CCVA)由IUCN研发,由3部分组成:(1)敏感性:ⅰ)生境专一性;ⅱ)生理耐受幅度;ⅲ)依赖环境诱因(如产卵日期、迁移时间等);ⅳ)依赖种间相互作用;ⅴ)稀有性;(2)适应能力:ⅰ)迁移能力;ⅱ)进化能力;(3)暴露度:ⅰ)温度变化;ⅱ)降雨量变化。综合敏感性、暴露度和适应能力,评估物种面对未来气候变化的脆弱性[69- 70]。物种敏感性和暴露度较高,而适应能力较低,其脆弱度较高[69]。Foden等采用CCVA框架对全球鸟类、两栖类和珊瑚类进行脆弱性评估,气候变化将会导致全球6%—9%鸟类、11%—15%两栖类和6%—9%珊瑚变得高度脆弱,且这些物种将会有灭绝的风险[71]。类似评估如非洲中东部28%两栖类、20%鸟类、6%淡水鱼类、30%兽类和42%爬行类,气候变化将会导致这些物种变得非常脆弱,其中5种两栖类、4种鸟类、5种淡水鱼类和1种爬行类由于受到气候变化的影响,将会有灭绝的风险[72]。CCVA评估方法比较容易掌握,但该方法针对全球物种,评估指标要充分考虑全球普遍可行性,因此,可能会忽略一些很有价值的评估指标。

3.3.3 EPA脆弱性评估框架

由美国环境保护局(Environmental Protection Agency, EPA)研发了一个框架来评估气候变化背景下受威胁或濒危物种脆弱性[73]。EPA框架由4个模块组成,模块1由11个当前面临压力指标组成(如种群数量大小和分布范围变化、生活繁殖史等非气候变化影响因素);模块2由10个气候变化影响指标组成(如极值天气);模块3整合模块1和模块2,最终评估濒危物种面对未来气候变化的脆弱性;模块1和模块2每个指标都给出一个可信度评分,模块4则综合模块1和模块2可信度评分,评估最终结果的可信度。利用EPA框架评估金颊黑背林莺(Dendroicachrysoparia)、斑点林鸮(StrixOccidentalislucida)、格雷厄姆山红松鼠(TamiasciurusHudsonicusgrahamensis)等濒危物种脆弱性[73- 74];Moyle等通过修改部分EPA指标评估美国加利福尼亚州本土和外来入侵鱼类脆弱性,结果表明82%的本地鱼类和19%外来入侵鱼类被评估为较高脆弱,并且认为气候变化将会显著地改变该区域鱼类群系[75];Gardali等结合CCVI指数和EPA框架,对加利福尼亚州濒危鸟类进行脆弱性评估,然后整合该地区鸟类濒危级别与脆弱程度,得出应该针对该区域哪些鸟类采取优先保护行动[65]。EPA框架评估过程相对简单,主要针对于研究较为充分的濒危物种,其评估结果可信度较高,但也正是因为评估对象仅仅为濒危物种,导致其评估物种较少。

3.3.4 SVAS评估系统

SAVS评估系统(A System for Assessing Vulnerability of Species to Climate Change, SAVS)由美国国家林业局以问卷的形式调查气候变化对陆生脊椎动物的影响[76]。问卷表由气候变化影响物种栖息地、生理、物候、以及种间关系4部分组成。该系统评价准则:脆弱性高的物种,抵抗力较弱;脆弱低的物种,抵抗力较强[76]。研究人员利用SAVS对美国新墨西哥洲117种脊椎动物评估,认为未来气候变化将会对该区域物种生境、物候、生理等方面产生强烈影响,许多物种未来将会变得高度脆弱,如索诺兰叉角羚(AntilocapraAmericanasonoriensis)和沙漠龟(Gopherusmorafkai)等,种群数将会明显下降[77- 78]。

3.3.5 SIVVA评估指数

由气候变化引起的海平面上升对生物多样性的间接影响同样受到关注。Reece和Noss参照IUCN红色名录、NatureServe物种保护级别、以及CCVI等评估方法,研发出一套只适合评估气候变化背景下沿海低洼区域物种脆弱度的指数,称之为SIVVA指数(Standardized Index of Vulnerability and Value, SIVVA)[79]。SIVVA指数增加了如经济价值、侵蚀度、盐度等指标,使其更加符合栖息在沿海低洼区域物种的特点。目前,SIVVA评估方法仅用于佛罗里达洲低洼区野生动植物脆弱性评估,Reece等对该区域300种动植物进行脆弱性评估,认为气候变化引起的海平面上升影响该区域的生物多样性,应该对迈阿密蓝蝶(Cyclargusthomasibethunebakeri)、凯鹿等物种采取优先保护措施[80]。同时,相比于栖息在其它生境中的同类物种,栖息在佛罗里达洲礁岛上的部分濒危物种由于适应能力较差和迁移限制,无法适应气候变化带来影响,将会有灭绝的风险,且认为成功保护的可能性较低[81]。

4 脆弱性指数评估指标

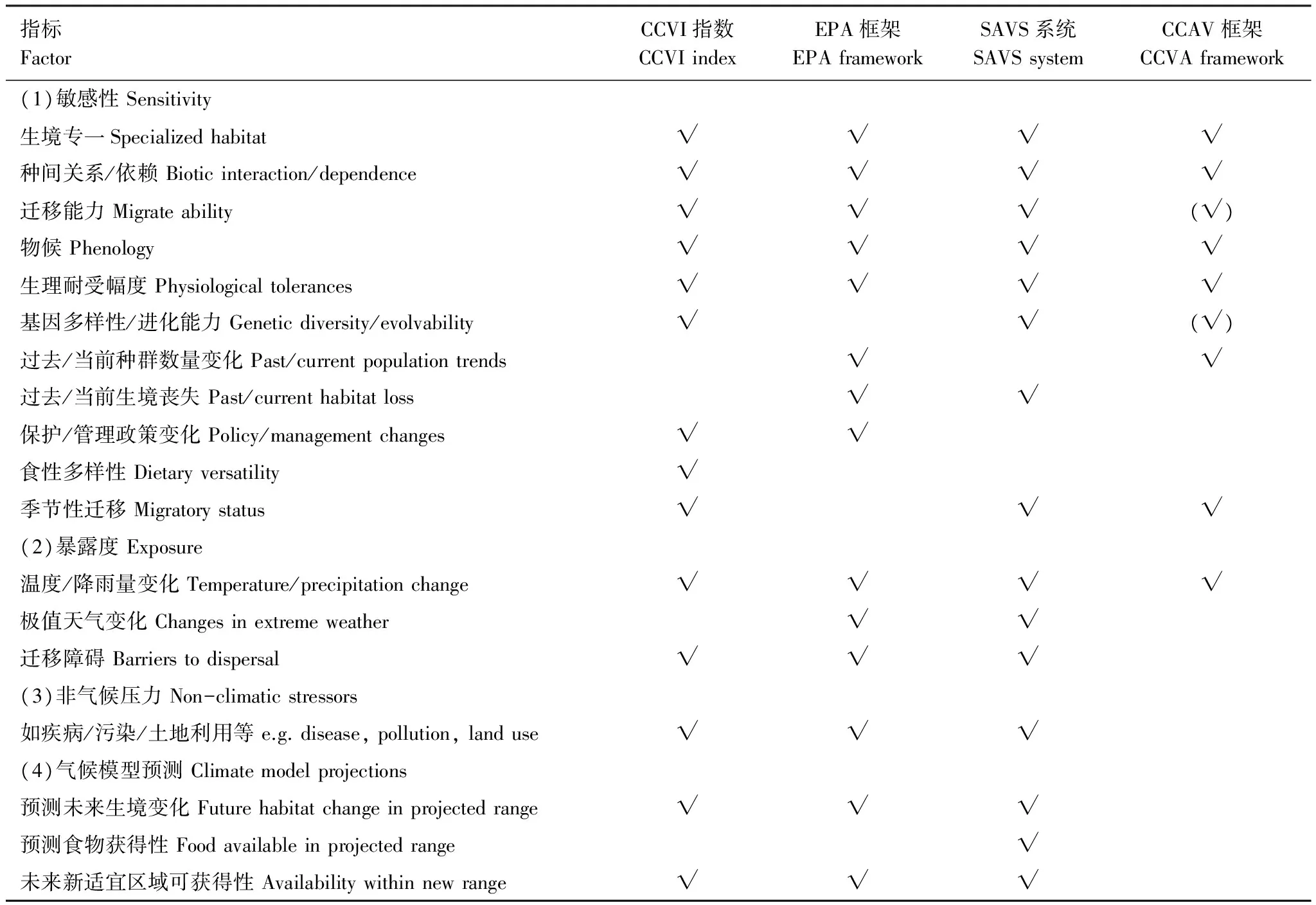

气候变化影响涉及野生动物的方方面面,采用哪些指标来衡量其脆弱性还没有一个明确的标准[34]。利用敏感性、暴露度和适应能力作为评估指标,是所有方法的共同点[26,76]。然而,每种评估方法所选取的指标存在一定的差异,本文总结CCVI指数、CCVA框架、EPA框架、以及SAVS系统所使用的指标[30,64,71,73,76](表1)。总结以上脆弱性指数评估方法,将评估指标归纳为敏感性、暴露度、非气候压力和气候模型预测4类。敏感性指标主要包括生境专一、种间关系、迁移能力、物候、生理耐受幅度、基因多样性、季节性迁移、种群动态变化、生境变化、保护管理措施、食性多样性等;物种对以上指标较为敏感,则气候变化将会对其产生较大影响,如生境高度专一的物种,如果其所依赖的生境受到气候变化较大的影响,物种可能会面临着较大的灭绝风险;又如高度依赖人类保护和管理的物种,其命运比那些不依赖的物种更容易受到气候变化的影响。暴露度主要包括温度和降雨量变化、极值天气、迁移障碍等指标;评估区域如果未来温度升高幅度较大,降雨和干旱模式不断变化,可预见极端天气事件频繁发生,将会对该区域物种产生重大影响;如果人类工程或自然存在的障碍阻隔了物种的迁移路线,将会近一步加剧物种的脆弱性。非气候因素,如评估区域当前存在疾病传播、环境污染、人为干扰等因素影响,同样会加剧物种的脆弱性。气候模型预测主要包括未来适宜生境变化、适宜生境的可获得性、食物可获得性等指标;利用模型预测气候变化对物种的影响,预测结果为提出物种的适应性保护对策提供参考依据。指标的使用具有灵活性,针对不同区域、不同物种脆弱性评估,所选取的指标也存在差异,在进行评估时,应该筛选出符合该区域物种特点的评估指标[34,65,75]。

脆弱性评估最大的挑战在于指标信息的可获得性,只有少数受人类关注的物种研究较为充分,大部分物种的基础信息匮乏,如物候变化、生理反应、模型预测等,缺乏足够的信息去完成全面的评估[26,34]。然而,气候变化对生物多样性的影响速度快,等收集完物种的全部信息,其生境可能已经丧失,甚至存在濒临灭绝的风险[26,75]。因此,对于基础信息有限的物种,评估其脆弱性时通常采取以下方法对相关信息进行估计:(1)参照与其密切相关的同类物种信息[26];(2)参考已发表的文献、文学报道、实验或野外观察数据[30,55,65];(3)采用专家小组意见[73];(4)一些信息如生理耐受幅度,可采用物种在评估区域已经历的历史温度或降雨量变化替代[64,82];(5)部分信息如基因多样性、生态学进化等,只能不充分的理解[26,73]。CCVI指数在处理信息不足时,如敏感性指标,只需满足其中10条,评估结果就有效[64];EPA框架中的指标可以灵活使用,应根据评估物种的实际情况出发选择指标,或补充一些该框架没有考虑到的指标[75]。每种评估方法在对物种进行评估时,会考虑指标信息的不确定性,对其获取信息的可信度进行评分,评估物种脆弱程度的可信度。值得注意的是,气候变化是一个及其复杂的科学问题,其中的不确定性是客观存在的,脆弱性评估并不需要考虑非常精确的定值,其评估结果代表物种近似的脆弱级别[75]。

表1 不同评估方法气候变化脆弱性指标

(√): CCVA框架定义为适应能力

5 脆弱性评估结果的应用

脆弱性评估主要目的是为了提出适应性保护对策,减缓气候变化给野生动物带来的不利影响[55]。本文将脆弱性评估结果的应用其及相应的保护对策总结为以下几点:(1)明确物种脆弱性因素:在制定适应性保护对策时,必需掌握物种当前面临的压力(即主要威胁因子),才能制定适宜的对策,可借鉴脆弱性评估结果,即物种面对当前压力的敏感性[28,73]。通过对物种脆弱性评估,使管理决策者能够通过修改保护对策来适应不断变化的情况,采取如长期系统监测、减小人为干扰、加强外来物种入侵监测等措施,并制定相关规划、政策、制度和措施,来减小物种面临的威胁[55,83-84];(2)确定脆弱物种:脆弱性评估能很好的筛选出优先保护物种,筛选出那些不能通过自身扩散或进化能力来适应气候变化的物种[78],这些物种需要借助人类的干预措施来消除气候变化带来的不利影响,如采取构建生态廊道等适应性保护对策,来减小脆弱物种交流及扩散的阻碍[31];(3)评估生境脆弱区:利用模型预测物种当前和未来适宜生境变化,找出气候变化会导致适宜生境丧失或降级的区域(即脆弱区域)[85],在脆弱区域采取生境恢复、加强管理以及长期监测等保护策施,防止生境丧失或降级[86- 87];(4)寻找庇护所:利用模型预测物种当前和未来适宜生境变化,找出适宜生境没有发生变化的区域,或当前不适宜生境在未来转化为适宜生境的区域,这些区域将会成为野生动物躲避未来气候灾害的庇护所,需加强这些区域的监督与管理,同时规划野生动物迁移到庇护所的生态廊道,减小其迁移阻障[88- 89];(5)评估保护区成效性:利用空缺分析(Gap analysis)来评估已建立的自然保护区是否能够覆盖到物种当前和未来适宜生境[2,90],采取调整保护区或建立新的保护区等措施,提高保护区间的联通性和整体保护能力[91- 92];(6)IUCN分类依据:气候变化背景下物种脆弱性评估结果被IUCN作为在红色名录中受威胁等级分类依据,将有助于评估物种受到国际社会的关注,对物种的保护工作起到一定的促进和推动作用[93]。

6 结语

由于气候变化的不确定性,以及人类对野生动物认知的局限性,很多问题还无法完全明白,但大量证据都表明气候变化确实在发生,尤其是近年来极端气候事件频繁发生[94],迫切需要探寻气候变化与野生动物的关系,以便更好的应对气候变化带来的不利影响,缓解气候变化给野生动物带来的危害[95- 96]。我国动物资源非常丰富,地域分布广泛,气候变化正影响着我国野生动物是毋庸置疑的[97- 98],如已观察到气候变暖加速我国鸟类区系变化[99]、改变昆虫类和两栖类春季和秋季物候[100]、可能诱导鼠灾暴发[101- 102]、导致物种局部消失[103]。我国开展气候变化背景下野生动物脆弱性评估工作主要利用模型测物种未来适宜生境的变化,且大部分研究对象针对单一物种,如大熊猫[49- 50]、雪豹[89]、野骆驼(Camelusferus)[104]、川金丝猴(Rhinopithecusroxellana)[105]、黑脸琵鹭(Plataleaminor)[106]、黑头噪鸦(Perisoreusinternigrans)[107]、四川山鹧鸪(Arborophilarufipectus)[108]等,少数研究针对多个物种,如鸟类[96]、两栖类[109]、有蹄类[110]。虽然模型预测能准确评估出物种在哪些区域脆弱,但仅仅局限于大尺度上的影响(如气候、地形等非生物因子),而忽略了在小尺度上的影响(如物种间相互作用、耐受范围、生活史等生物因子),而往往局部的气候灾害带来的影响可能更加深远[111-112]。因此,在对物种进行脆弱性评估时,建议将气候变化、物种自身的生物学特性以及模型预测等信息进行综合考虑,有助于充分认识气候变化对野生动物的影响,为野生动物适应气候变化保护对策的制定提供更加合理的科学依据。

总体来讲,我国在开展气候变化背景下野生动物脆弱性评估这方面的研究相对较少,在制定野生动物保护对策时,大多数仅仅只考虑物种当前面临的压力,忽略气候变化未来可能带来的影响,适应气候变化对策也同样仅局限于概念,没有形成有效的技术[23]。基于此,建议我国科研人员和管理决策者从以下几方面进一步研究,提出长期有效的适应性保护对策来减小气候变化对野生动物的危害。第一,建立长期系统的野生动物监测计划(如种群动态、物候、地理分布范围等),为野生动物脆弱性评估工作提供数据支持;第二,基于国内当前对野生动物基础信息的了解程度,还无法建立起像北美自然服务组织那样如此全面的生物多样性数据库,但可以尝试以自然保护区尺度来建立数据平台,并实现数据共享;第三,加强气候变化监测研究,提高气候变化预测能力,并建立预防极端气候灾害对野生动物影响的机制;第四,学习和引进新的脆弱性评估方法,建立气候变化背景下野生动物脆弱性评估的指标体系,能有效地评估未来气候变化情景下我国野生动物的脆弱程度;第五,开展野生动物对气候变化适应过程和能力分析,如物种迁移能力和进化能力,为适应性保护对策提供理论和技术支持;第六,完善野生动物的适应性管理方式,加强宣传教育,减少人为因素加剧气候变化给野生动物带来的危害。

[1] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate change (IPCC). Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC, 2014: 151.

[2] Bellard C, Bertelsmeier C, Leadley P, Thuiller W, Courchamp F. Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecology Letters, 2012, 15(4): 365- 377.

[3] Cramer W, Yohe G W, Auffhammer M, Huggel U, Molau U, Da Sliva Dias M A F, Solow A, Stone D A, Tibig L. Detection and attribution of observed impacts // Field C B, Barros V R, Dokken D J, Mach K J, Mastrandrea M D, Bilir T E, Chatterjee M, Ebi K L, Estrada Y O, Genova R C, Girma B, Kissel E S, Levy A N, MacCracken S, Mastrandrea P R, White L L, eds. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspect. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 2014: 979- 1037.

[4] Chen I C, Hill J K, Ohlemüller R, Roy D B, Thomas C D. Rapid range shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science, 2011, 333(6045): 1024- 1026.

[5] Ancillotto L, Santini L, Ranc N, Maiorano L, Russo D. Extraordinary range expansion in a common bat: the potential roles of climate change and urbanisation. The Science of Nature, 2016, 103(3/4): 15- 15.

[6] Auer S K, Martin T E. Climate change has indirect effects on resource use and overlap among coexisting bird species with negative consequences for their reproductive success. Global Change Biology, 2013, 19(2): 411- 419.

[7] Yan C, Stenseth N C, Krebs C J, Zhang Z B. Linking climate change to population cycles of hares and lynx. Global Change Biology, 2013, 19(11): 3263- 3271.

[8] Yang L H, Rudolf V H W. Phenology, ontogeny and the effects of climate change on the timing of species interactions. Ecology Letters, 2013, 13(1): 1- 10.

[10] Charmantier A, Gienapp P. Climate change and timing of avian breeding and migration: evolutionary versus plastic changes. Evolutionary Applications, 2014, 7(1): 15- 28.

[11] Koen E L, Bowman J, Murray D L, Wilson P J. Climate change reduces genetic diversity of Canada Lynx at the trailing range edge. Ecography, 2013, 37(8): 375- 762.

[12] Rinawati F, Stein K, Lindner A. Climate change impacts on biodiversity-the setting of a lingering global crisis. Diversity, 2013, 5(1): 114- 123.

[13] Urban M C. Accelerating extinction risk from climate change. Science, 2016, 348(6234): 571- 573.

[14] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Adoption of the Paris agreement. Report No. FCCC/CP/2015/L.9/Rev.1. 2015. http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf.

[15] Thomas C D, Cmeron A, Green R E, Bakkenes M, Beaumont L J, Collingham Y C, Erasmus B F N, de Siqueira M F, Grainger A, Hannah L, Hughes L, Huntley B, van Jaarsveld A S, Midgley G F, Miles L, Ortega-Huerta M A, Peterson A T, Phillips O L, Williams S E. Extinction risk from climate change. Nature, 2004, 427(6970) 145- 148.

[16] Malcolm J R, Liu C R, Neilson R P, Hansen L, Hannah L. Global warming and extinctions of endemic species from biodiversity hotspots. Conservation Biology, 2006, 20(2): 538- 548.

[17] Pereira H M, Leadley P W, Proença V, Alkemade R, Scharlemann J P W, Fernandez-Manjarrés J F, Araújo M B, Balvanera P, Biggs R, Cheung W W L, Chini L, Cooper H D, Gilman E L, Guénette S, Hurtt G C, Huntington H P, Mace G M, Oberdorff T, Revenga C, Rodrigues P, Scholes R J, Sumaila U R, Walpole M. Scenarios for global biodiversity in the 21st century. Science, 2010, 330(6010): 1496- 1501.

[18] Levinsky I, Skov F, Svenning J C, Rahbek C. Potential impacts of climate change on the distributions and diversity patterns of European mammals. Biodiversity and Conservation, 2007, 16(13): 3830- 3816.

[19] Arribas P, Abellán P, Velasco J, Bilton D, Millán A, Sánchez-Fernández D. Evaluating drivers of vulnerability to climate change: a guide for insect conservation strategies. Global Change Biology, 2012, 18(7): 2135- 2146.

[20] Foden W B, Butchart S H M, Stuart S N, Vié J C, Akçakaya H R, Angulo A, DeVantier L M, Gutsche A, Turak E, Cao L, Donner S D, Katariya V, Bernard R, Holland R A, Hughes A F, O′Hanlon S E, Garnett S T,ekerciolu C H, Mace G M. Identifying the world′s most climate change vulnerable species: a systematic trait-based assessment of all birds, amphibians and corals. PLoS One, 2013, 8(6): e65427.

[21] Oppenheimer M M, Campos M, Warren R, Birkmann J, Luber G, O′Neill B, Takahashi K. Emergent risks and key vulnerabilities // Field C B, Barros V R, Dokken D J, Mach K J, Mastrandrea M D, Bilir T E, Chatterjee M, Ebi K L, Estrada Y O, Genova R C, Girma B, Kissel E S, Levy A N, MacCracken S, Mastrandrea P R, White L L, eds. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspect. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 2014: 1039- 1099.

[22] 环境保护部. 中国生物多样性保护战略与行动计划. 北京: 中国环境科学出版社, 2011.

[23] 吴建国, 吕佳佳, 艾丽. 气候变化对生物多样性的影响: 脆弱性和适应. 生态环境学报, 2009, 18(2): 693- 703.

[24] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate change (IPCC). Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007: 976- 976.

[25] Gallopin G C. Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Global Environmental Change, 2006, 16(3): 293- 303.

[26] Williams S E, Shoo L P, Isaac J L, Hoffmann A A, Langham G. Towards an integrated framework for assessing the vulnerability of species to climate change. PLoS Biology, 2008, 6(12): 2621- 2626.

[27] Foden W B, Pacifici M, Hole D. Chapter 2. Setting the scene // Foden W B, Young B E, eds. IUCN SSC guidelines for assessing species′ vulnerability to climate change. Version 1.0. Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No.59. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK, 2016: 5- 11.

[28] Glick P, Stein B A, Edelson N A. Scanning the Conservation Horizon: A Guide to Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment. Washington, D. C: National Wildlife Federation, 2011.

[29] Dawson, T P, Jackson S T, House J I, Prentice I C, Mace G M. Beyond predictions: biodiversity conservation in a changing climate. Science, 2011, 332(6025): 53- 58.

[30] Rowland E L, Davison J E, Graumlich L J. Approaches to evaluating climate change impacts on species: a guide to initiating the adaptation planning process. Environment Management, 2011, 47(3): 322- 337.

[31] Stein B A, Glick P, Edelson N A, Staudt A. Climate-Smart Conservation: Putting Adaptation Principles Into Practice. Washington, D. C: National Wildlife Federation, 2011.

[32] Nicotra A B, Beever E A, Robertson A L, Hofmann G E, O′Leary J. Assessing the components of adaptive capacity to improve conservation and management efforts under global change. Conservation Biology, 2015, 29(5): 1268- 1278.

[33] Beever E A, O′Leary J, Mengelt C, West J M, Julius S, Green N, Magness D, Petes L, Stein B, Nicotra A B, Hellmann J J, Robertson A L, Staudinger M D, Rosenberg A A, Babij E, Brennan J, Schuurman G W, Hofmann G E. Improving conservation outcomes with a new paradigm for understanding species′ fundamental and realized adaptive capacity. Conservation Letters, 2016, 9(2): 131- 137.

[34] Tuberville T D, Andrews K M, Sperry J H, Grosse A M. Use of the NatureServe climate change vulnerability index as an assessment tool for reptiles and amphibians: lessons learned. Environmental Management, 2015, 56(4): 822- 834.

[35] Pearson R G, Dawson T P. Predicting the impacts of climate change on the distribution of species: are bioclimate envelope models useful? Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2003, 12(5): 361- 371.

[36] Elith J, Graham C H, Anderson R P, Dudík M, Ferrier S, Guisan A, Hijmans R J, Huettmann F, Leathwick J R, Lehmann A, Li J, Lohmann L G, Loisell B A, Manion G, Moritz C, Nakamura M, Nakazawa Y, Overton J M M, Peterson A T, Phillips S J, Richardson K, Scachetti-Pereira R, Schapire R E, Soberón J, Williams S, Wisz M S, Zimmermann N E. Novel methods improve prediction of species′ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography, 2006, 29(2): 129- 151.

[37] Songer M, Delion M, Biggs A, Huang Q Y. Modeling impacts of climate change on giant panda habitat. International Journal of Ecology, 2012, 2012: 108752.

[38] Lawler J J, Shafer S L, Bancroft B A, Blaustein A R. Projected climate change impacts for the amphibians of the Western Hemisphere. Conservation Biology, 2010, 24(1): 38- 50.

[39] Thuiller W, Lavorel S, Araújo M B. Niche properties and geographical extent as predictors of species sensitivity to climate change. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2005, 14(4): 347- 357.

[40] Heikkinen R K, Luoto M, Leikola N, Pöyry J, Settele J, Kudrna O, Marmion M, Fronozek S, Thuiller W. Assessing the vulnerability of European butterflies to climate change using multiple criteria. Biodiversity and Conservation, 2010, 19(3): 695- 723.

[41] Kane A, Burkett TC, Kloper S, Sewall J. Virginia′s Climate Modeling and Species Vulnerability Assessment: How Climate Data Can Inform Management and Conservation. Reston, Virginia: National Wildlife Federation, 2013.

[42] Lawler J J, Shafer S L, White D, Kareiva P, Maurer E P, Blaustein A R, Bartlein P. Projected climate-induced faunal change in the western Hemisphere. Ecology, 2009, 90(3): 588- 597.

[43] Sinervo B, Mendez-de-la-Cruz F, Miles D B, Heulin B, Bastiaans E, Cruz M V S, Lara-Resendiz R, Martínez-Méndez N, Calderón-Espinosa M L, Meza-Lázaro R N, Gadsden H, Avila L J, Morando M, De La Riva I J, Sepulveda P V, Rocha C F D, Ibargüengoytía N, Puntriano C A, Massot M, Lepetz V, Oksanen T A, Chapple D G, Bauer A M, Branch W R, Clobert J, Sites J W Jr. Erosion of lizard diversity by climate change and altered thermal niches. Science, 2010, 328(5980): 894- 899.

[44] Pearson R G, Stanton K T, Shoemaker M E, Aiello-Lammens M E, Ersts P J, Horning N, Fordham D A, Raxworthy C J, Ryu H Y, McNees J, Akçakaya H R. Life history and spatial traits predict extinction risk due to climate change. Nature Climate Change, 2014, 4(3): 217- 221.

[45] Polocazanska E S, Brown C J, Sydeman W J, Kiessling W, Schoeman D S, Moore P J, Brander K, Bruno J F, Buckley J B, Burrows M T, Duarte C M, Halpern B S, Holding J, Kappel C V, O′Connor M I, Pandolfi J M, Parmesan C, Schwing F, Thompson S A, Richardson A J. Global imprint of climate change on marine life. Nature Climate Change, 2013, 3(10): 919- 925.

[46] Adams-Hosking C, Grantham H S, Rhodes J R, McAlpine C, Moss P T. Modeling climate-change-induced shifts in the distribution of the koala. Wildlife Research, 2011, 38(2): 122- 130.

[47] MacCracken J G, Garlich-Miller J, Snyder J, Meehan R, Meehan R. Bayesian belief network models for species assessments: An example with the pacific walrus. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 2013, 37(1): 226- 235.

[48] Forrest J L, Wikramanayake E, Shresha R, Shrestha R, Areendran G, Gyeltshen K, Maheshwari A, Mazumdar S, Naidoo R, Thapa G J, Thapa K. Conservation and climate change: Assessment the vulnerability of snow leopard habitat to treeline shift in the Himalaya. Biological Conservation, 2012, 150(1): 129- 135.

[49] Fan J T, Li J S, Xia R, Hu L L, Wu X P, Li G. Assessing the impact of climate change on the habitat distribution of the giant panda in the Qinling Mountains of China. Ecological Modelling, 2014, 274: 12- 20.

[50] Li R Q, Xu M, Wong M H G, Qiu S, Li X H, Ehrenfeld D, Li D M. Climate change threatens giant panda protection in the 21st century. Biological Conservation, 2015, 182: 93- 101.

[51] Bertelsmeier C, Guénard B, Courchamp F. Climate change may boost the invasion of the Asian needle ant. PLoS One, 2013, 8(10): e75438.

[52] Ficetola G F, Maiorano L, Falcucci A, Dendoncker N, Boitani L, Padoa-Schioppa E, Miaud C, Thuiller W. Knowing the past to predict the future: land-use change and the distribution of invasive bullfrogs. Global Change Biology, 2010, 16(2): 528- 537.

[53] Reshetnikov A N, Ficetola G F. Potential range of the invasive fish rotan (Perccottusglenii) in the Holarctic. Biological Invasions, 2011, 13(12): 2967- 2980.

[54] Young B E, Hall K R, Byers E, Gravuer K, Hammerson G, Redder A, Szabo K. Rapid assessment of plant and animal vulnerability to climate change // Brodie J, Post E, Doak D, eds. Wildlife Conservation in A Changing Climate. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. 2012: 129- 150.

[55] Pacifici M, Foden W B, Visconti P, Watson J E M, Butchart S H M, Kovacs K M, Scheffers B R, Hole D G, Martin T G, Akçakaya H R, Corlett R T, Huntley B, Bickford D, Carr J A, Hoffmann A A, Midgley G F, Pearce-Kelly P, Pearson R G, Williams S E, Willis S G, Young B, Rondinini C. Assessing species vulnerability to climate change. Nature Climate Change, 2015, 5(3): 215- 225.

[56] Naveda-Rodríguez A, Vargas F H, Kohn S, Zapata-Ríos G. Andean Condor (Vulturgryphus) in Ecuador: Geographic distribution, population size and extinction risk. PLoS One, 2016, 11(3): e0151827.

[57] Jenouvrier S, Caswell H, Barbraud C, Hollan M, Stroeve J, Weimerskirch H, Cohen J E. Demographic models and IPCC climate projections predict the decline of an emperor penguin population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106(6): 1844- 1847.

[58] Overgaard J, Kearney M R, Hoffmann A A. Sensitivity to thermal extremes in AustralianDrosophilaimplies similar impacts of climate change on the distribution of widespread and tropical species. Global Change Biology, 2014, 20(6): 1738- 1750.

[59] Huey R B, Kearney M R, Krockenberger A, Holtum J A M, Jess M, Williams S E. Predicting organismal vulnerability to climate warming: roles of behaviour, physiology and adaptation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2012, 19(1596): 1665- 1679.

[60] Sunday J, Bates A E, Dulvy N K. Thermal tolerance and the global redistribution of animals. Nature Climate Change, 2012, 2(9): 686- 690.

[61] Lancaster L T. Widespread range expansions shape latitudinal variation in insect thermal limits. Nature Climate Change, 2016, 6(6): 618- 621.

[62] Schloss C A, Nuez T A, Lawler J J. Dispersal will limit ability of mammals to track climate change in the Western Hemisphere. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2012, 109(22): 8606- 8611.

[63] Morin X, Thuiller W. Comparing niche-and process-based models to reduce prediction uncertainty in species range shifts under climate change. Ecology, 2009, 90(5): 1301- 1313.

[64] Young B E, Byers E, Hammerson G, Frances A, Oliver L, Treher A. Guidelines for Using the NatureServe Climate Change Vulnerability Index (Release 3. 0). Arlington, VA: NatureServe, 2015.

[65] Gardali T, Seavy N E, DiGaudio R, Comrack L A. A climate change vulnerability assessment of California′s at-risk bird. PLoS One, 2012, 7(3): e29507.

[66] Young B E, Dubois N S, Rowland E L. Using the climate change vulnerability index to inform adaptation planning: lessons, innovations, and next steps. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 2014, 39(1): 174- 181.

[67] Siegel R B, Pyle P, Thorne J H, Holguin A J, Howell C A, Stock S, Tingley M W. Vulnerability of birds to climate change in California′s Sierra Nevada. Avian Conservation and Ecology, 2014, 9(1): 7- 7.

[68] Dubois N, Caldas A, Boshoven J, Delach A. Integrating Climate Change Vulnerability Assessments Into Adaptation Planning: A Case Study Using the NatureServe Climate Change Vulnerability Index to Inform Conservation Planning for Species in Florida. Washington D. C: Defenders of Wildlife, 2011.

[69] Foden W, Mace G M, Vié J C, Angulo A, Butchart S, DeVantier L, Dublin H, Gutsche A, Stuart S N, Turak E. Species susceptibility to climate change impacts // Vié J C, Hiton-Taylor C, Stuart S N, eds. The 2008 review of the IUCN Red List of threatened species. Switzerland: IUCN Gland, 2008.

[70] Foden W B, Young B E. IUCN SSC guidelines for assessing species′ vulnerability to climate change. Version 1. 0. occasional paper of the IUCN species survival commission No. 59. Cambridge. UK and Gland, Switzerland: IUCN Species Survival Commission, 2016: X+114pp.

[71] Foden W B, Butchart S H M, Stuart S N, Vié J C, Akçakaya H R, Angulo A, DeVantier L M, Gutsche A, Turak E, Cao L, Donner S D, Katariya V, Bernard R, Holland R A, Hughes A F, O′Hanlon S E, Garnett S T,ekerciolu C H, Mace G M. Identifying the world′s most climate change vulnerable species: a systematic trait-based assessment of all birds, amphibians and corals. PLoS One, 2013, 8(6): e65427.

[72] Carr J A, Outhwaite W E, Goodman G L, Oldfield T E E, Foden W B. Vital but Vulnerable: Climate Change Vulnerability and Human Use of Wildlife in Africa′s Albertine Rift. Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 48. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: IUCN, 2013: Xii+224.

[73] U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). A Framework for Categorizing the Relative Vulnerability of Threatened and Endangered Species to Climate Change (External Review Draft). Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2009.

[74] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Final Recovery Plan for the Mexican Spotted Owl (Strixoccidentalislucida), first revision. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. New Mexico, USA: Albuquerque, 2012: 413- 413.

[75] Moyle P B, Kiernan K D, Crain P K, Muiones R M. Climate change vulnerability of native and alien freshwater fishes of California: a systematic assessment approach. PLoS One, 2013, 8(5): e63883.

[76] Bagne K E, Friggens M M, Finch D M. A System for Assessing Vulnerability of Species (SAVS) to Climate Change. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR- 257. Fort Collins, CO. U. S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 2011: 28- 28.

[77] Bagne K E, Finch DM. Vulnerability of Species to Climate Change in the Southwest: Threatened, Endangered, and Risk Species at the Barry M. Goldwater Range, Arizona. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR- 257. Fort Collins, CO: U. S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 2012: 139- 139.

[78] Friggens M M, Finch D M, Bagne K E, Coe S J, Hawksworth D L. Vulnerability of species to climate change in the Southwest: terrestrial species of the middle Rio Grande. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR- 306. Fort Collins, CO. U. S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 2013: 191- 191.

[79] Reece J S, Noss R F. Prioritizing species by conservation value and vulnerability: a new index applied to species threatened by sea-level rise and other risks in Florida. Natural Areas Journal, 2014, 34(1): 31- 45.

[80] Reece J S, Noss R F, Oetting J, Hoctor T, Volk M. A vulnerability assessment of 300 species in Florida: threats from sea level rise, land use, and climate change. PLoS One, 2013, 8(11): e80658.

[81] Benscoter A M, Reece J S, Noss R F, Brandt L A, Mazzotti F J, Romaach S S, Watling J I. Threatened and endangered subspecies with vulnerable ecological traits also have high susceptibility to sea level rise and habitat fragmentation. PLoS One, 2013, 8(8): e70647.

[82] Addo-Bediako A, Chown S L, Gaston K J. Thermal tolerance, climatic, variability and latitude. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2000, 267(1445): 739- 745.

[83] Jiang G S, Ma J Z, Zhang M H, Stott P. Multiple spatial-scale resource selection function models in relation to human disturbance for moose in northeastern China. Ecological Research, 2009, 24(2): 423- 440.

[84] Jeschke J M, Strayer D L. Usefulness of bioclimatic models for studying climate change and invasive species. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2008, 1134(1): 1- 24.

[85] Carvalho S B, Brito J C, Crespo E J, Possingham H P. From climate change predictions to actions-conservation vulnerable animals groups in hotspots at a regional scale. Global Change Biology, 2010, 16(12): 3257- 3270.

[86] Hole D G, Huntley B, Arinaitwe J, Butchart S H M, Collingham Y C, Fishpool L D C, Pain D J, Willis S G. Toward a management framework for networks of protected areas in the face of climate change. Conservation Biology, 2011, 25(2): 305- 315.

[87] Beechie T, Imaki H, Greene J, Wade A, Wu H, Pess G, Roni P, Kimball J, Stanford J, Kiffney P, Mantua N. Restoring salmon habitat for a changing climate. River Research and Applications, 2013, 28(8): 939- 960.

[88] Ashcroft M B. Identifying refugia from climate change. Journal of Biogeography, 2010, 37(8): 1407- 1413.

[89] Li J, McCarthy T M, Wang H, Weckworth B V, Schaller G B, Mishra C, Lu Z, Beissinger S R. Climate refugia of snow leopards in high Asia. Biological Conservation, 2016, 203: 188- 196.

[90] Belle E M S, Burgess N D, Misrachi M, Arnell A, Masumbuko B, Somda J, Hartley A, Jones R, Janes T, McSweeney C, Mathison C, Buontempo C, Butchart S, Willis S G, Baker D J, Carr J, Hughes A, Foden W, Smith R J, Smith J, Stolton S, Dudley N, Hockings M, Mulongoy J, Kingston N. Climate change impacts on biodiversity and protected area in West Africa, Summary of the main outputs of the PARCC project, Protected area resilient to climate change in West Africa. Cambridge, UK: UNEP-WCMC, 2016.

[91] Hannah L, Midgley G, Andelman S, Araujo M, Hughes G, Martinez-Meyer E, Pearson R, Williams P. Protected area needs in a changing climate. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 2007, 5(3): 131- 138.

[92] Gross J, Watson J, Woodley S, Welling L, Harmon D. Responding to Climate Change: Guidance for Protected Area Managers and Planners. IUCN WCPA Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. XX. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN, 2015.

[93] Foden W, Akçakaya R. Chapter 7. The IUCN Red List and Climate Change Vulnerability // Foden W B, Young B E, eds. IUCN SSC Guidelines for Assessing Species′ Vulnerability to Climate Change. Version 1. 0. Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 59. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK, 2016: 57- 58.

[94] 科学技术部社会发展科技司, 中国21世纪义程管理中心. 适宜气候变化国家战略研究. 北京: 科学出版社, 2011.

[95] Wu X P, Lin X, Zhang Y, Gao J J, Guo L, Li Z S. Impacts of climate change on ecosystem in priority areas of biodiversity conservation in China. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2014, 59(34): 4668- 4680.

[96] Li X Y, Clinton N, Si Y L, Liao J S, Liang L, Gong P. Projected impacts of climate change on protected birds and nature reserves in China. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2015, 60(19): 1644- 1653.

[97] 蒋志刚. 保护生物学原理. 北京: 科学出版社, 2014.

[98] Shen Z H, Ma K P. Effects of climate change on biodiversity. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2014, 59(34): 4637- 4638.

[99] 杜寅, 周放, 舒晓莲, 李一琳. 全球气候变暖对中国鸟类区系的影响. 动物分类学报, 2009, 34(3): 664- 674.

[100] Ge Q S, Wang H J, Rutishauser T, Dai J H. Phenological response to climate change in China: a meat-analysis. Global Change Biology, 2015, 24(1): 265- 274.

[101] Jiang G S, Liu J, Xu L, Yu G R, He H L, Zhang Z B. Climate warming increases biodiversity of small rodents by favoring rare or less abundant species in a grassland ecosystem. Integrative Zoology, 2013, 8(2): 162- 174.

[102] Jiang G, Zhao T, Liu J, Xu L, Yu G, He H, Krebs C J, Zhang Z. Effects of ENSO-linked climate change and vegetation on population dynamics of sympatric rodent species in semiarid grasslands of Inner Mongolia, China. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 2011, 89(8): 679- 691.

[103] 马瑞俊, 蒋志刚. 全球气候变化对野生动物的影响. 生态学报, 2005, 25(11): 3061- 3066.

[104] 杨海龙. 库姆塔格沙漠地区野骆驼栖息地分析及气候变化影响[D]. 北京: 中国林业科学研究院, 2011.

[105] Luo Z H, Zhou S R, Yu W D, Yu H L, Yang J Y, Tian Y H, Zhao M, Wu H. Impacts of climate change on the distribution of Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecusroxellana) in Shennongjia area, China. American Journal of Primatology, 2014, 77(2): 135- 151.

[106] Hu J H, Hu H J, Jiang Z G. The impacts of climate change on the wintering distribution of an endangered migratory bird. Oecologia, 2010, 164(2): 555- 565.

[107] Lu N, Jing Y, Lloyd H, Sun Y H. Assessing the distributions and potential risks from climate change for the Sichuan Jay (Perisoreusinternigrans). The Condor, 2012, 114(2): 365- 376.

[108] Lei J C, Xu H G, Cui P, Guang Q W, Ding H. The potential effects of climate change on suitable habitat for the Sichuan hill partridge (Arborophilarufipectus, Boulton): Based on the maximum entropy modelling. Polish Journal of Ecology, 2014, 62(4): 771- 787.

[109] Duan R Y, Kong X Q, Huang M Y, Varela S, Ji X. The potential effects of climate change on amphibian distribution, range fragmentation and turnover in China. PeerJ, 2016, 4(10): e2185.

[110] Luo Z H, Jiang Z G, Tang S H. Impacts of climate change on distributions and diversity of ungulates on the Tibetan Plateau. Ecological Applications, 2015, 25(1): 24- 38.

[111] Suggitt A J, Gillingham P K, Hill J K, Huntley B, Kunin W E, Roy D B, Thomas C D. Habitat microclimates drive fine-scale variation in extreme temperatures. Oikos, 2011, 120(1): 1- 8.

[112] Franklin J, Davis F W, Ikegami M, Syphard A D, Flint L E, Flint A L, Hannah L. Modeling plant species distributions under future climates: how fine scale do climate projections need to be? Global Change Biology, 2013, 19(2): 473- 483.

Overviewofmethodsforassessingthevulnerabilityofwildlifetoclimatechange

LI Jia, LIU Fang, ZHANG Yu, XUE Yadong, LI Diqiang*

InstituteofForestryEcology,EnvironmentandProtection,ChineseAcademyofForestry,KeyLaboratoryofForestEcologyandEnvironmentofStateForestryAdministration,Beijing100091,China

In order to mitigate the widely recognized and harmful impacts of climate change on wildlife, it is imperative to assess the vulnerability of species to future climate change and to adopt adaptive conservation strategies. Assessments of climate change vulnerability make two essential contributions to adaptation planning, including the identification of species that are likely to be most strongly affected by climate change and the identification of underlying mechanisms that make these species vulnerable. Here, we define climate change vulnerability as the extent to which wildlife species will be affected by climate change, considering exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity, which we respectively define as extrinsic factors that will result from climate change (e.g., increasing temperature and precipitation and extreme weather), intrinsic species traits (e.g., biotic interactions and physiological tolerances), and the degree to which species are able to reduce or avoid the adverse effects of climate change through dispersal and plastic ecological or evolutionary responses. In this review, we describe the different methods used for assessing the vulnerability of wildlife to climate change, as well as the corresponding data requirements, and then address the uncertainty factors in each method and describe the importance of vulnerability assessments in designing adaptive climate change-related conservation strategies. The purpose of this review is to provide a reference for assessing the vulnerability of wildlife to climate change in China.

climate change; vulnerability; exposure; sensitivity; adaptation conservation strategies

国家科技支撑计划项目(2013BAC09B02);自然保护区生物标本资源共享子平台项目(2005DKA21404)

2016- 07- 30; < class="emphasis_bold">网络出版日期

日期:2017- 06- 01

*通讯作者Corresponding author.E-mail: lidq@caf.ac.cn

10.5846/stxb201607301564

李佳, 刘芳, 张宇, 薛亚东, 李迪强.气候变化背景下野生动物脆弱性评估方法研究进展.生态学报,2017,37(20):6656- 6667.

Li J, Liu F, Zhang Y, Xue Y D, Li D Q.Overview of methods for assessing the vulnerability of wildlife to climate change.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2017,37(20):6656- 6667.