日本小孩为何能独自上学?

By+Selena+Hoy

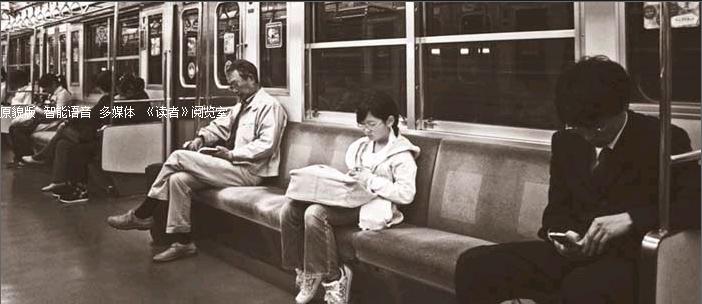

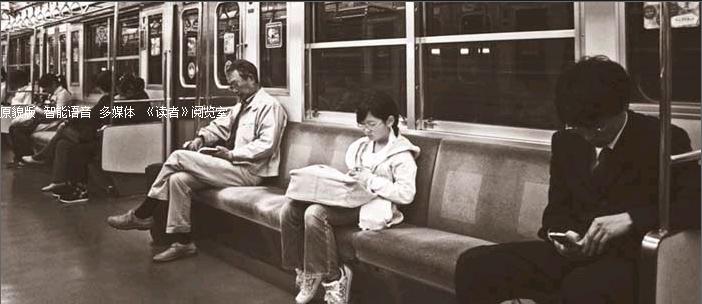

Its a common sight on Japanese mass transit: Children troop through train cars,1 singly or in small groups, looking for seats. They wear knee socks, polished patent-leather shoes, and plaid jumpers, with wide-brimmed hats fastened under the chin and train passes pinned to their backpacks.2 The kids are as young as six or seven, on their way to and from school, and there is nary a guardian in sight.3

A popular television show called Hajimete no Otsukai, or My First Errand, features children as young as two or three being sent out to do a task for their family.4 As they tentatively make their way to the greengrocer or bakery, their progress is secretly filmed by a camera crew.5 The show has been running for more than 25 years.

KaKaito, a 12-year-old in Tokyo, has been riding the train by himself between the homes of his parents, who share his custody6, since he was nine. “At first I was a little worried,” he admits, “whether I could ride the train alone. But only a little worried.” Now, he says, its easy. His parents were apprehensive7 at first, too, but they went ahead because they felt he was old enough, and lots of other kids were doing it safely.

“Honestly, what I remember thinking at the time is, the trains are safe and on time and easy to navigate8, and hes a smart kid,”Kaitos stepmother says. “I took the trains on my own when I was younger than him in Tokyo,” She recalls. “We didnt have cellphones back in my day, but I still managed to go from point A to point B on the train. If he gets lost, he can call us.”

What accounts for9 this unusual degree of independence? Not self-sufficiency, in fact, but “group reliance,” according to Dwayne Dixon, a cultural anthropologist who wrote his doctoral dissertation on Japanese youth.10 “[Japanese] kids learn early on that, ideally, any member of the community can be called on to serve or help others,” he says.

This assumption is reinforced at school,11 where children take turns cleaning and serving lunch instead of relying on staff to perform such duties. This “distributes labor across various shoulders and rotates expectations,12 while also teaching everyone what it takes to clean a toilet, for instance,”Dixon says.

Taking responsibility for shared spaces means that children have pride of ownership and understand in a concrete way the consequences of making a mess, since theyll have to clean it up themselves.13 This ethic14 extends to public space more broadly (one reason Japanese streets are generally so clean). A child out in public knows he can rely on the group to help in an emergency.

Japan has a very low crime rate, which is surely a key reason parents feel confident about sending their kids out alone. But small-scaled urban spaces and a culture of walking and transit use also foster safety and, perhaps just as important, the perception of safety.15

“Public space is scaled so much better—old, human-sized spaces that also control flow and speed,”16 Dixon notes. In Japanese cities, people are accustomed to walking everywhere, and public transportation trumps car culture;17 in Tokyo, half of all trips are made on rail or bus, and a quarter on foot. Drivers are used to sharing the road and yielding to pedestrians and cyclists.18

Kaitos stepmother says she wouldnt let a nine-year-old ride the subway alone in London or New York—just in Tokyo. Thats not to say the Tokyo subway is risk-free. The persistent problem of women and girls being groped, for example, led to the introduction of women-only cars on select lines starting in 2000.19 Still, many city children continue to take the train to school and run errands in their neighborhood without close supervision20.

By giving them this freedom, parents are placing significant trust not only in their kids, but in the whole community. “Plenty of kids across the world are self-sufficient,” Dixon observes. “But the thing that I suspect Westerners are intrigued by [in Japan] is the sense of trust and cooperation that occurs, often unspoken or unsolicited.”21

1. mass transit: 公共交通;troop: 成群結队地走。

2. knee sock: 半筒袜,及膝袜;polished: 擦亮的;patent-leather: 漆皮;plaid: 带格子图案的;jumper: 套头毛衫;widebrimmed: 宽边的;train pass: 火车通行证;pin to: 固定,别在……上。

3. nary:〈口〉(通常后接a或an)一个也没有的;guardian: 监护人。

4. errand: 差事,节目名称“My First Errand”的意思是“我第一次上街买东西”;feature: v. 由……主演。

5. tentatively: 尝试性地;greengrocer: 蔬菜水果商贩;film: v. 拍摄;camera crew: 摄制组。

6. custody: 抚养权。

7. apprehensive: 担心的,恐惧的。

8. navigate: 导航,引路。

9. account for: 解释,说明……的原因。

10. self-sufficiency: 自给自足,自我满足;group reliance: 团体依靠;anthropologist: 人类学家;doctoral dissertation: 博士论文。这里是说日本小孩的这种独立并非出于自身,而是由于全社会的保护。

11. assumption: 假设;reinforce: 强化。

12. 这给每个孩子都分了工,让他们轮换着完成任务。distribute: 分配;rotate: 轮换。

13. 在共享空间里承担起责任意味着孩子有一种主人翁的自豪感,而且也清楚地知道把事情搞砸的后果,因为他们必须自己收拾残局。concrete: 具体的,确实的。

14. ethic: 道德规范。

15. 但是城市区域小、人们倾向于步行以及习惯利用公共交通出行也增加了安全度,或者同样重要的,增强了人们的安全感。foster: 培养,促进;perception: 知觉,感受。

16.(日本)公共空间的大小也更为合适——那些年头已久的、只能容纳行人的区域也控制住了交通流速。scale: v. 改变……的大小。

17. be accustomed to: 习惯于;trump: 胜过,这里指公共交通工具比私家车多。

18. yield to: 屈从于,让步于,这里指让路;pedestrian: 行人;cyclist: 骑自行车的人。

19. persistent: 反复出现的;grope: 猥亵,摸;women-only car: 女性专用车厢,是为了保护女性不受性骚扰;select line: 专线,专列。

20. close supervision: 密切监督,严密监护。

21. suspect: 猜想;intrigue: 使好奇,使感兴趣;unsolicited: 主动提供的。

阅读感评

“自己走路去上学”,这在上世纪七八十年代的中国是再正常不过的事了。记得我的小学离家至少有两三站的距离,那个时代小地方没有什么公交,除了第一天由我爸爸陪同步行去上学外,直至毕业我都是自己走着去的。到了中学,离家距离也不近,地形环境还更复杂些,记得须沿着没有护栏的河堤走一段,再跨过一座同样没有栏杆的石桥,也从未有家人接送。但三十余年后的今天,小学生独自去上学,不用说在大城市,即便在小城镇,恐怕也已基本绝迹,甚至还有中学生每天需要人接送。

因此,当今六七岁的日本孩子居然还能像我们那代人一样独自走着去上学,而且成为日本街头常见的一景,就让人感到惊讶了。当然,这里的“走着(walk)”未必就是完全徒步,更多的情况可能是两头几百米步行,中间更长的路须搭乘公交或城铁等。笔者今年五月份在日本第二大城市大阪的街头,就常看见清晨有许多学生自己或步行或骑车去上学,下雨天也是如此。文章中说日本两三岁的小孩有时还被家人派去水果蔬菜店或面包房买东西,这让我想起自己小时候也曾为父母干过类似的事情,尤其是在他们做饭烧菜的当儿常被差到街上打酱油。文中还提到,东京一个12岁的离异家庭的孩子,从九岁起就能自己坐火车来往于父亲与母亲家,更是让人觉得有些不可思议。

对于日本孩子的这种“孤胆英雄”作风,我们往往会归结于其家庭、学校教育中对于其独立性的培养。然而本文却说,“这种超常独立程度的来由,事实上并非出于自足(self-sufficiency),而是因为有团体依靠(group reliance)”。也就是说,并非因为日本孩子的能力超强,而是有集体这座大靠山让其无所畏惧。中国传统上也是讲求集体精神轻个人主义的,但在实践中却几乎倒了个个儿。文章说,日本孩子从小就知道,社会里的任何一个成员都能被招来为他人服务或帮助他人。这种观念是“为共同的空间承担责任”(taking responsibility for shared spaces),通过他们在学校里参与打扫、帮助供应午餐等轮换活动逐渐养成。笔者想起,前些年在上海、广州等一些大城市的火车站,向路人问路要先交钱,说是“有偿问询服务”。后来,我们的社会又流行起“不同陌生人交谈”的“文化”,尤其是妇女与儿童要特别小心。在这样的公共空间里行走,投过来的都是贪婪与不信任的眼光,当然是没有什么安全感的。诚然,世界各地有独立能力的孩子有的是,但日本父母如此放心让孩子独自在城市里行走,恐怕很大程度上确实是出于某种心照不宣的集体信任感与社会帮扶度,也就是原文中所说的“group reliance”。

文章中还提到,营造安全环境,除了“犯罪率低”外,还需有一些必备的“硬件”与“软件”,如日本的“小规模的城市空间”(small-scaled urban spaces)与“徒步与采用公共交通的文化”(a culture of walking and transit use)。据笔者理解,前者指的是城市的公共空间设计非常人性化,也就是说街道不会太宽,所有路口都设置便于行人优先通行的标志。这不仅充分考虑到了人流与车流的速度,還让机动车驾驶者习惯与行人及骑行者分享道路或者给后者让道,而非以高人一等的姿态与后者抢道甚至逼迫后者为其让道,至少这些都给人以安全感。后者指的是日本人已把步行以及使用公共交通当做生活的一部分和出行的首选。

反观我们周边的情形,每周五下午及周日傍晚,北京一些学校周边一公里左右的范围内总是挤满了车,为的是接孩子回家过周末及送孩子来上学。笔者的几位中年女性同事都苦于没时间好好备课做学问,原因竟都是得陪着孩子上各种培训班。这些父母宁可忍受交通拥堵、无处合法停车的种种麻烦,也要接送陪伴孩子。这一方面是父母爱的奉献,另一方面也体现了一种无奈心理,即对于独自行动的孩子安全的恐惧。其中一部分原因是可以理解的,但我们似乎也不应忘记这样一个道理:“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself”(我们唯一需要恐惧的是恐惧本身)——富兰克林·罗斯福。