Early Enteral Combined with Parenteral Nutrition Treatment for Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: Effects on Immune Function, Nutritional Status and Outcomes△

Ming-chao Fan, Qiao-ling Wang, Wei Fang, Yun-xia Jiang, Lian-di Li, Peng Sun, and Zhi-hong Wang*

Early Enteral Combined with Parenteral Nutrition Treatment for Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: Effects on Immune Function, Nutritional Status and Outcomes△

Ming-chao Fan1, Qiao-ling Wang2, Wei Fang1, Yun-xia Jiang3, Lian-di Li1, Peng Sun4, and Zhi-hong Wang5*

1Department of NeurologicalIntensive Care Unit,4Department of Neurosurgery,5Department of Geriatric Medicine, the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao, Shandong 266003, China2Community Medical Service Center of Shuiqinggou Street, Qingdao, Shandong 266042, China3Nursing school, Medical College of Qingdao University, Qingdao, Shandong 266003, China

enteral nutrition; parenteral nutrition; severe traumatic brain injury; immune function; complication

Objective To compare the conjoint effect of enteral nutrition (EN) and parenteral nutrition (PN) with single EN or PN on immune function, nutritional status, complications and clinical outcomes of patients with severe traumatic brain injury (STBI).

Methods A prospective randomized control trial was carried out from January 2009 toMay 2012 in Neurological Intensive Care Unit (NICU). Patients of STBI who met the enrolment criteria (Glasgow Coma Scale score 6~8; Nutritional Risk Screening≥3) were randomly divided into 3 groups and were admi- nistrated EN, PN or EN+PN treatments respectively. The indexes of nutritional status, immune function, complications and clinical outcomes were examined and compared statistically.

Results There were 120 patients enrolled in the study, with 40 pationts in each group. In EN+PN group, T lymthocyte subsets CD3+%, CD4+%, ratio of CD3+/CD25+, ratio of CD4+/CD8+, the plasma levels of IgA, IgM, and IgG at 20 days after nutritional treatment were significantly increased compared to the baseline(=4.32-30.00,<0.01), and they were significantly higher than those of PN group (=2.44-14.70;<0.05,or<0.01) with exception of CD4+/CD8+, higher than those of EN group (=2.49-13.31,<0.05, or<0.01) with exceptions of CD3+/CD25+, CD4+/CD8+, IgG and IgM. For the nutritional status, the serum total protein, albumin, prealbumin and hemoglobin were significantly higher in the EN (=5.87-11.91;<0.01) and EN+PN groups (=6.12-13.12;<0.01) than those in PN group after nutrition treatment. The serum prealbumin was higher in EN+PN group than that in EN group(=2.08;<0.05). Compared to the PN group, the complication occurrence rates of EN+PN group were significantly lower in stress ulcer (22.5%. 47.5%;2= 8.24,<0.01), intracranial infection (12.5% vs 32.5%;2= 6.88,<0.01) and pyemia (25.0%. 47.5%;2= 6.57,<0.05). Compared to the EN group, the complication occurrence rates of EN+PN group were significantly lower in aspirated pneumonia (27.5%. 50.0%;2= 6.39,<0.05), hypoproteinemia (17.5%. 55.0%;2= 18.26,<0.01) and diarrhea (20.0%. 60.0%;2= 20.00,<0.01). The EN+PN group also had significant less length of stay in NICU (=2.51, 4.82;0.050.01), number of patients receiving assisted mechanical ventilation (2= 6.08, 12.88;<0.050.01) and its durations (=3.41, 9.08;<0.050.01), and the death rate (2=7.50, 16.37;<0.050.01) than those of EN or PN group.

Conclusion Early EN+PN treatment could promote the recovery of the immune function, enhance nutritional status, decrease complications and improve the clinical outcomes in patients with severe traumatic brain injury.

Chin Med Sci J 2016; 31(4):213-220

EUROLOGICALpatients with severe traumatic brain injury (STBI) are at high risk for develo- ping nutrition-related complications due to primary injury and secondary injury cascade that ensues.1The STBI patients are metabolic hyperactivity and in stringent state.2Immunological function, especially cellular immune function which induces anti-infection capability, was depressed in most of STBI patients.1, 3-6One of important reasons may be lack of enough nourishment intake due to the state of unconsciousness for a long time. Malnutrition not only delays neurofunctional recovery and depresses organism immunity, but also induces some grave complications,which could increase the mortality and prolong hospitalization of STBI.7-8Nutritional support, which may improve neurological outcome of brain injury, has been considered as an important issue in trauma care in the past three decades, but its timing and route have not been well established.9Nutrition for STBI patients could be provided by both parenteral and enteral route, and the latter is commonly considered as a better choice for critically ill patients. The benefit of enteral nutrition (EN) on mucosal integrity and the prevention of enterogenic infection may well explain the superiority of EN over parenteral nutrition (PN).5, 10However, STBI patients may not tolerate enteral feeding well and regurgitant pneumonia may occur commonly.11Early EN has an important influence on nonspecific cellular immunity and specific cellular immunity.4EN intolerance generally manifests itself in the form of increased gastric residuals, gastro- oesophageal reflux, vomiting, abdominal distention and diarrhea.3Due to the restricted speed and dose of enteral feeding and thereafter insufficient energy delivery, a combined approach of EN and PN may be the best choice for nutrition treatment.

In this prospective randomized control trial, we compared the treatment effect of EN, PN and EN+PN on immune function, clinical complications and outcomes of patients with STBI in Neurological Intensive Care Unit (NICU).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design and patients enrollment

This single centric prospective and observational rando- mized control trial was carried out from January 2009 toMay 2012 in NICU. Consecutive eligible patients were assigned to EN group, PN group and EN+PN groups randomly according to the sequence of their assigned hospital record number. This study had been approved by the local institu- tional review board and the Human Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. Informed consent had been acquired by patients’ guardians. Our study abides by the Declaration of Helsinki, the related laws and regulations.

Patient who was admitted to the NICU with the diagnosis of STBI were enrolled in the study if met the inclusion criteria:1) Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score:6-8; 2) Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS)≥ 3.The exclusion criteria including: 1) Glucocorticoid and blood products were used during study; 2) Hemodynamic instability; 3) Immunosup- pressive drug was used in the past 6 months; 4) Patients received radiotherapy or chemotherapy in the past one year; 5) Injured more than 12 hours early before admission; 6) died within 3 weeks; 7) had previous history of metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus (irritable hyperglycemia due to injury was exceptional).

Nutrition therapies

All patients were given nasogastric tube intubation and central venous catheterization within 48 hours after admission. Patients in PN group were given fully parenteral alimentation through the central venous catheter within 48hours after admission. PN was prepared by Intravenous drug dispensing center with ratio of 2:1 for carbohydrates to lipids, and ratio of 100:1 for calorie nitrogen ratio. Patients in EN group were given Nasogastric tube accom- panied by subsequent suctioning gastric juice and pumping EN (energy density 6.28 kJ/ml, Nutrison Fibre, NUTRICIA, Holland) within 48hours after admission. An increase of dosage to the maximum (1500 ml/d) was made gradually in 7 days with pumping speed under 75 ml/h. Only normal sodium, glucose and saline were given as medicamentous dissolvent in vein. Within 48hours after admission, patients in the EN+PN group suction gastric juice and pump EN with nasogastric tube. An increase of dosage to the maximum of 1000 ml/d was made gradually in 7 days, with pumping speed not exceeding 50ml/h. The insufficient energy was supplied by PN. All 120 patients were given energy as 105-126 kJ/kg·d. For any patients of the three groups, supplements such as vitamins, microelement, natrium and kalium were given according to patients’ status, and the headstock was raised to 30° to avoid the counter-flow conventionally if necessary.

Observation, measurements and data collection

For each patient, the data of age, gender and body mass index were recorded on admission. All patients were drawn blood in the morning of the first and the twentieth day on an empty stomach. Immune function evaluations included T lympholeukocyte subsets (CD3+%, CD4+%, CD3+/ CD25+ and CD4+/CD8+) and plasma immunoglobulin (IgA, IgM and IgG) were measured. Nutritional status measurements including the serum total protein, serum albumin, serum prealbumin and hemoglobin. The complications we observed including diarrhea, stress ulcer, intracranial infection,pyemia, hypoproteinemia and aspirated pneumonia. The Length of stay (LOS) in Neurological intensive care unit (NICU), number of patients receiving assisted mechanical ventilation and its dura- tions, and death rate were documented as the clinical outcomes.

Statisticalanalysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 13.5. The immunological indexes and the nutrition status measure- ments of each group were analyzed and compared using Matched-pairs-test, and their differences between pre- and after the nutritional treatment were compared using q test. The variance analysis was performed to detect the statistical significance among three groups.2test was used to detect significant difference for the enumerative data of complications and outcomes between the EN+PN group and the EN or PN group respectively. All quantitative data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD).values of <0.05were considered as significant and of <0.01 as highly significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of enrolled patients

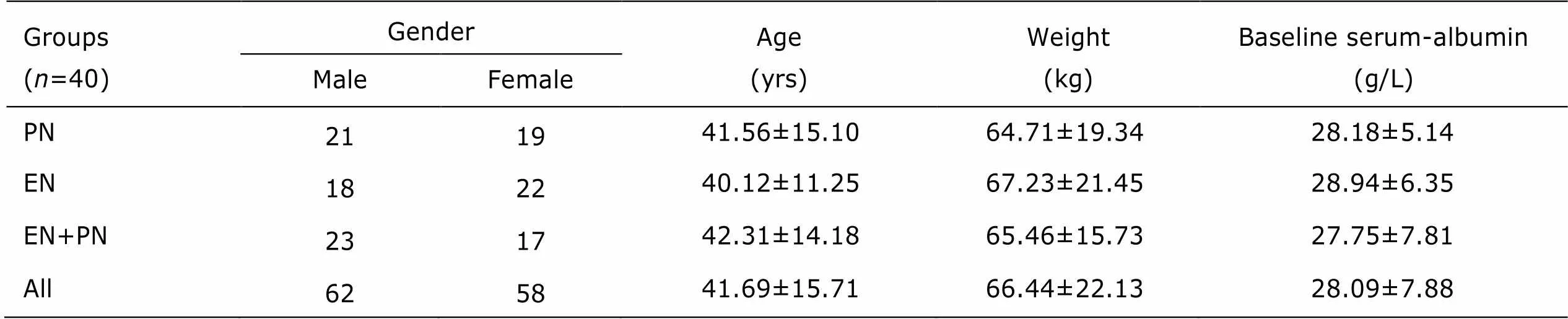

A total of 120 patients were enrolled in this study, with ageranged from 16 to 68 years (mean 41.25±12.34 years), and 48.33% (=58) were female. The characteristics of enrolled patients in each group were shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference among three groups in terms of age, sex, weight and serum-albumin at baseline (>0.05).

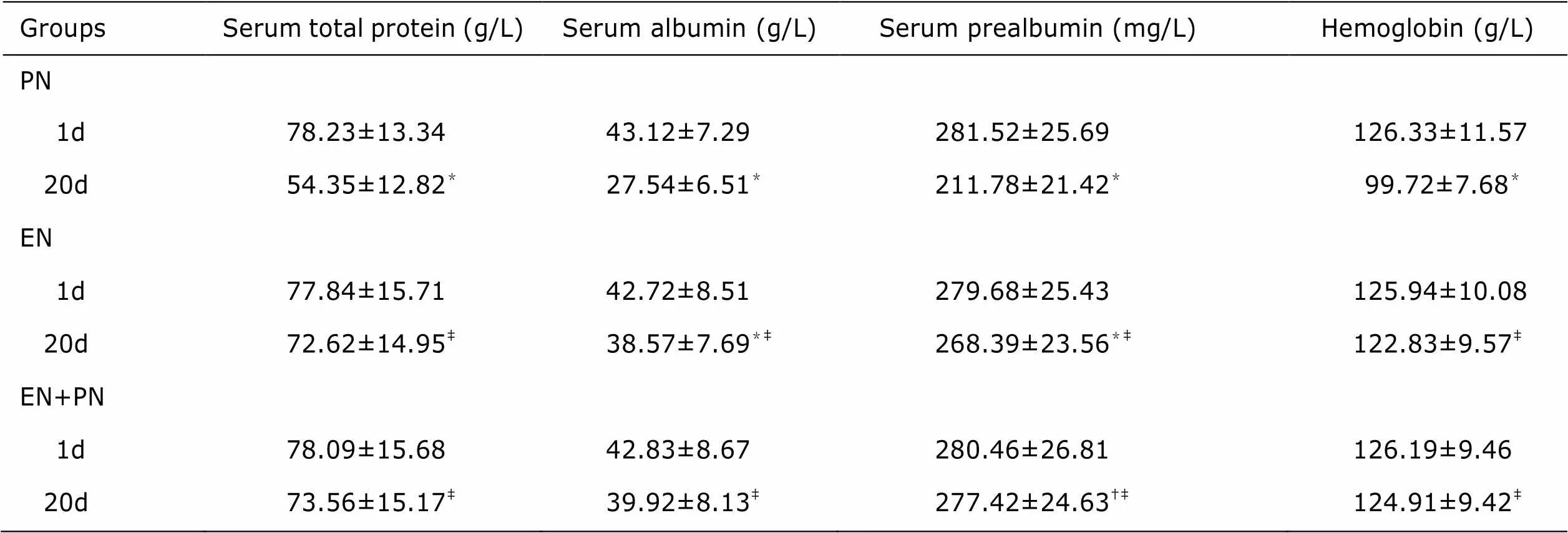

Nutrition status

After nutrition treatment the serum total protein, albumin, prealbumin and hemoglobin were significantly decreased in PN group (=8.15-13.18;<0.01); in the EN group, only the serum albumin (=2.06,<0.05) and prealbumin (=2.29;<0.05) decreased significantly. The serum total protein, albumin, prealbumin and hemoglobin were significantly higher in the EN (=5.87-11.91;<0.01) and EN+PN groups (=6.12-13.12;<0.01) after nutrition treatment. than those in PN group. The serum prealbumin was higher in EN+PN group than that in EN group(=2.08;<0.05).The summary of the data and the statistical results is displayed in Table 2.

Table 1. Characteristics of enrolled patients§

§: Plus-minus values are mean±SD. PN: parenteral nutrition; EN: enteral nutrition.

Immune status

The T cells subsets and immunoglobulin before and after nutritional treatment in each group are summarized in Table 3. Compared to the baseline measurements, T lymphocyte subgroup CD3+% and CD4+%, the ratio of CD3+/CD25+, and the plasma levels of IgA and IgG in PN group significantly increased after nutritional treatment (=2.07-7.42;<0.05,<0.01). T lymphocyte subgroup CD3+% and CD4+%, the ratio of CD3+/CD25+, and the plasma levels of IgA and IgG significantly increased after nutritional treatment in EN group (=2.19-13.11;<0.05,<0.01) as well. In EN+PN group T lymphocyte subgroup CD3+% and CD4+%, the ratio of CD4+/CD8+ and CD3+/ CD25+, and the plasma levels of IgA, IgM and IgG signi- ficantly increased after nutritional treatment (=4.32-30.00;<0.01).

Table 2. Measurements of nutritional status before and after nutritional treatment in three groups§ (n=40)

§: Plus-minus values are mean±SD.1d: 1 day; 20d: 20 days after the nutritional treatment.P<0.05 or<0.01 compared with that of 1d;†<0.05 compared with EN group;‡<0.01 compared with PN group.

Table 3.Measurements of T cells subsets and immunoglobulinbefore and after nutritional treatment in three nutrition treatment groups§ (n=40)

§: Plus-minus values are mean±SD.P<0.05 or<0.01 compared with that of 1d;†<0.01 compared with EN group;‡<0.05 or<0.01 compared with PN group.

There were no significant difference of the baseline CD3+%, CD4+%, CD3+/CD25+ and CD4+/CD8+, and plasma level of IgA, IgM and IgG among the three groups (>0.05). After nutritional treatment, most of above measurements increased significantly (<0.05, or<0.01) except for CD4+/CD8+. Additionally, compared with the PN group,the EN group had higher levels of mean CD3+%, CD4+%, CD3+/CD25+, IgA and IgG (=2.02-6.29;<0.05or<0.01), whereas the EN+PN group had higher level of mean CD3+%, CD4+%, CD3+/CD25+, IgA, IgM and IgG (=2.44-14.70;<0.05or<0.01). Furthermore, CD3+%, CD4+%, CD3+/CD25+, IgA and IgG in the EN+PN group were significantly higher than those in the EN group (=2.49-13.31;<0.05 or<0.01).

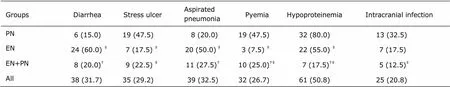

Complications and clinical outcomes

As shown in Table 4, compared to the PN group, the complication occurrence rates of EN+PN group were significantly lower in stress ulcer (22.5%. 47.5%;2=8.24,<0.01) , intracranial infection (12.5%. 32.5%;2=6.88,<0.01) and pyemia (25.0%. 47.5%;2=6.57,<0.05); Compared to the EN group, the complicationoccurrence rates of EN+PN group were significantly lower in aspirated pneumonia (27.5%. 50.0%;2=6.39,< 0.05), hypoproteinemia (17.5%. 55%;2=18.26,<0.01) and diarrhea (22.0%. 60.0 %;2=20.00,<0.01).

For the outcomes, in EN+PN group, the LOS in NICU (=2.51;<0.05), number of patients receiving assisted mechanical ventilation (40.0%. 62.5%;2=6.08;<0.05) and the durations (=3.41;<0.01), the death rate (10.0%. 30.0%;2=7.50;<0.01) were significantly lower than those in EN group; and the LOS in NICU (=4.82;<0.01), number of patients receiving assisted mechanical ventilation (40.0%. 72.5%;2=12.88;<0.01) and the durations (=9.08;<0.01), the death rate (10.0%. 42.5%;2=16.37;<0.01) were also significantly lower than those in PN group. The summary of outcome data and the statistical results are displayed in Table 5.

DISCUSSION

STBI patients are at high risk of becoming malnou- rished due to body's stress hypermetabolism followed by a hypercatabolic state with insufficient nutritional supply.12More than 40% critically ill patients who suffer from malnutrition would have impaired immune function and ventilatory drive.13As reported by Krakau1incidence of inchoate malnutrition caused by trauma was as high as 68% in neurosurgical STBI patients. In our practice, over 80% STBI patients would even experience malnutrition. Nutritional therapy has been considered as a crucial part of comprehensive therapy for STBI patients due to the hypermetabolic response. The nutritional status is closely associated with the prognosis of STBI patients. In order to improve the prognosis of STBI patients, the generally accepted strategies of nutritional supply are to provide nutritional therapy according to the condition of patients, prevent nutritional deficiencies and avoid complications related to nutrition delivery.13-14

Table 4. Complications occurrence of STBI patients in three nutrition treatment groups [n (%), n = 40]

§: Plus-minus values are mean±SD.†<0.01compared with EN group;‡<0.05 or<0.01 compared with PN group.

Table 5. Clinical outcomes of STBI patients in three nutrition treatment groups (n=40)

§: Plus-minus values are mean±SD. LOS: length of stay; NICU: neurological intensive care unit; AMV: assisted mechanical ventilation.†<0.01 or<0.05 compared with EN group;‡<0.01 or<0.05 compared with PN group.

The immune response is one of the most important part in body’s responses to severe injury. Most of STBI patients with malnutrition have a hypo-immune state.15STBI is directly followed by a decreased number of circulating T-lymphocytes, imbalance of helper cells and impaired activation and proliferation of T-lymphocyte.16The immune system disorder plays an important role in pathophysiology of brain injury.17In our study, the plasma levels of CD3+%, CD4+%, CD3+/CD25+, IgA, IgM and IgG were suppressed in the initial stage of brain trauma which indicated an impaired immune function; the humoral immunity and cellular immunity were ameliorated after nutritional therapy in EN and EN+PN groups. These results showed that early EN enhances immune function status and decrease the incidence of infectious complications in STBI patients, which was consistent with the results in previous reports.18-20However, physiology mechanism of the impact of early EN on immune function is obscure and there has been no relevant report yet.

The gastrointestinal tract may play an important role in EN nutrition improving immune function of critically ill patients. The gastrointestinal tract works not only as a site of nutrient absorption but also as a primary immune organ, where 70-80% of the body’s lymphoid tissue locates.17The gut is another intricate immune system that consists of three components: the epithelium, the mucosal immune system and the commensal normal flora, which plays an important role in the immune response.5EN has many advantages such as less complications and improved immune function.8, 21Compared with PN, EN has the functions to maintain the integrality of gut barrier, and inhibit gut mucosal atrophy and abnormities in gut mucosal permea- bility.11EN has been proved efficient in restoring blood lymphocyte stimulation capacity, which reflects the function of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Gln-glutamine and dietary fiber could be supplied in EN. Gln-glutamine, synthesized and released from skeletal muscles into the systemic circulation, is the energy source for leukomonocyte and macrophage, which has a visible effect on recovering the immune function. Dietary fiber could clean up the intestinal tract, promote the refreshment of enterocyte, and maintain the function of the gastrointestinal tract.

Interestingly, the gut is a reservoir of bacteria and endotoxin, which may be the cause of nosocomial infections and sepsis syndrome.22The absence of enteral feeding induces atrophy of gut mucosal because the enterocyte cannot obtain enough nutrients from the intestinal. Mucosal atrophy may be the reason of the translocation of bacteria or endotoxin into the portal circulation.23The gastrointestinal tract plays a major role in the development of PN-associated pyemia. Enterogenic infection is one of the major reasons for multiple organ failure in STBI patients. The gut-associated lymphoid tissue can be protective against airway or intracranial infection under EN, and stop the bacterial translocation. Many studies have shown that early feeding can provide exogenous substrates to protect visceral protein and fat, improve immune competence, reduce infection and complications, promote neurological recovery, and decrease fatalities in surgical and injured patients.1, 9, 10, 24

However, total EN at incipience was unsuitable because of the general intolerance of gastrointestinal tract,3which induces silent pulmonary aspiration and the consequent pneumonia in comatose patients.25The reasons may lie in that low pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter accompanied with severe head injury increase the rate of regurgitation;26gastric emptying is prolonged and abnormal in 80% of STBI patients;27the capability of gastrointestinal motility is subdued in comatose state in most patients. Since many STBI patients have delayed gastric emptying during the first several days and do not tolerate gastric feeding, the speed and volume dose of enteral feeding have to be restricted and energy delivery is usually insufficient.

In EN+PN group, the early introduction of a short course PN was associated with low rates of aspirated pneumonia and alvine profluvium. Early supplemental PN should be considered in STBI patients.28The enteral refeeding syndrome is one of complications for total PN. Continuous EN is effective for the syndrome.29In the EN+PN group of this study, the rates of stress ulcer, intracranial infection and pyemia were lower than those in PN group; the rates of aspirated pneumonia and diarrhea were lower than those in EN group; the LOS in NICU, number of people receiving assisted mechanical ventilation and their durations were shorter than those in EN or PN group; the death rate was lower than that in PN group. These results indicated that early EN+PN nutritional support was associated with degraded complications and improved clinical outcomes in STBI patients.

In summary, we proposed that EN+PN treatment within 48 hours for neurosurgical STBI patients were superior to the single EN or PN treatment in promoting immune function recovery in STBI patients. The mechanism of early EN+PN improving the immune function of neuro- surgical severe trauma patients requires further investi- gations. The early EN+PN treatment could degrade the complication rate and improve the clinical outcomes of STBI patients in NICU.

1. Krakau K, Hansson A, Karlsson T, et al. Nutritional treatment of patients with severe traumatic brain injury during the first six months after injury. Nutrition 2007; 23: 308-17.

2. Wang D, Zheng SQ, Chen XC, et al. Comparisons between small intestinal and gastric feeding in severe traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and meta- analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Neurosurg 2015; 123: 1194-201.

3. Tan M, Zhu JC, Yin HH. Enteral nutrition in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: reasons for intolerance and medical management. Br J Neurosurg 2011; 25: 2-8.

4. Beier-Holgersen R, Brandstrup B. Influence of postoper- ative enteral nutrition on cellular immunity. A random double-blinded placebo controlled clinical trial. Int J Colorectal Dis 2012; 27: 513-20.

5. Lee JS, Jwa CS, Yi HJ, et al. Impact of early enteral nutrition on in-hospital mortality in patients with hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage. J Korean Neuro- surg Soc 2010; 48: 99-104.

6. Mrlian A, Smrcka M, Klabusay M. The importance of immune system disorders related to the Glasgow Outcome Score in patients after severe brain injury. Bratisl Lek Listy 2007; 108: 329-34.

7. Perel P, Yanagawa T, Bunn F, et al.Nutritional support for head-injured patients. Cochrane DatabaseSyst Rev 2006; CD001530.

8. Probst P, Keller D, Steimer J, et al. Early combined parenteral and enteral nutrition for pancreaticodene- ctomy-retrospective cohort analysis. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2016; 6: 68-73.

9. Chiang YH, Chao DP, Chu SF, et al. Early enteral nutrition and clinical outcomes of severe traumatic brain injury patients in acute stage: a multi-center cohort study. J Neurotrauma 2012; 29: 75-80.

10. Spanier BW, Bruno MJ, Mathus-Vliegen EM. Enteral nutrition and acute pancreatitis: a review. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2011; 2011. pii: 857949.

11. Altintas ND, Aydin K, Türkoğlu MA, et al. Effect of enteral versus parenteral nutrition on outcome of medical patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Nutr Clin Pract 2011; 26: 322-9.

12. Aadal L, Mortensen J, Nielsen JF. Weight reduction after severe brain injury: a challenge during the rehabilitation course. J Neurosci Nurs 2015; 47: 85-90.

13. Wang G, Chen H, Liu J, et al. A comparison of postoperative early enteral nutrition with delayed enteral nutrition in patients with esophageal cancer. Nutrients 2015; 7: 4308-17.

14. Quenot JP, Plantefeve G, Baudel JL, et al. Bedside adherence to clinical practice guidelines for enteral nutrition in critically ill patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a prospective, multi-centre, observational study. Crit Care 2010; 14: R37.

15. Minard G, Kudsk KA, Melton S, et al. Early versus delayed feeding with an immune-enhancing diet in patients with severe head injuries. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2000; 24: 145-9.

16. Smrcka M, Mrlian A, Karlsson-Valik J, et al. The effect of head injury upon the immune system. Bratisl Lek Listy 2007; 108: 144-8.

17. Langkamp-Henken B, Glezer JA, Kudsk KA. Immunologic structure and function of the gastrointestinal tract. Nutr Clin Pract 1992; 7: 100-8.

18. Motoori M, Yano M, Yasuda T, et al. Relationship between immunological parameters and the severity of neutropenia and effect of enteral nutrition on immune status during neoadjuvant chemotherapy on patients with advanced esophageal cancer. Oncology 2012; 83: 91-100.

19. Li JH, Han L, Du TP, et al. The effect of low-nitrogen and low-calorie parenteral nutrition combined with enteral nutrition on inflammatory cytokines and immune functions in patients with gastric cancer: a double blind placebo trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2015; 19: 1345-50.

20. Bakiner O, Bozkirli E, Giray S, et al. Impact of early versus late enteral nutrition on cell mediated immunity and its relationship with glucagon like peptide-1 in intensive care unit patients: a prospective study. Crit Care 2013; 17: R123.

21. Zhou WC, Li YM, Zhang H, et al. Therapeutic effects of endoscopic therapy combined with enteral nutrition on acute severe biliary pancreatitis. Chin Med J 2011; 124: 2993-6.

22. Yu G, Chen G, Huang B, et al. Effect of early enteral nutrition on postoperative nutritional status and immune function in elderly patients with esophageal cancer or cardiac cancer. Chin J Cancer Res 2013; 25: 299-305.

23. O’Leary MJ, Coakley JH. Nutrition and immunonutrition. Br J Anaesth 1996; 77: 118-27.

24. Cook AM, Peppard A, Magnuson B. Nutrition considera- tions in traumatic brain injury. Nutr Clin Pract 2008; 23: 608-20.

25. Hansen TS, Larsen K, Engberg AW. The association of functional oral intake and pneumonia in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008; 89: 2114-20.

26. Saxe JM, Ledgerwood AM, Lucas CE, et al. Lower esophageal sphincter dysfunction precludes safe gastric feeding after head injury. J Trauma 1994; 37: 581-6.

27. Kao CH, ChangLai SP, Chieng PU, et al. Gastric emptying in head-injured patients. Am J Gastroenterol 1998; 93:1108-12.

28. Bochicchio GV, Bochicchio K, Nehman S, et al. Tolerance and efficacy of enteral nutrition in traumatic brain-injured patients induced into barbiturate coma. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2006; 30: 503-6.

29. Aissaoui Y, Hammi S, Tagajdid R, et al. Refeeding syndrome: a forgotten and potentially lethal entity. Med sante Trop 2016; 26: 213-5.

for publication July 4, 2016.

Tel: 86-532-82912326, E-mail: fanmcchina@126.com

△Supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong province (Y2008C35) and Technology Supporting Program of Qingdao (12-1-3-5-(1)-nsh).

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2016年4期

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2016年4期

- Chinese Medical Sciences Journal的其它文章

- Clinical Observation of Bevacizumab Combined with S-1 in the Treatment of Pretreated Advanced Esophageal Carcinoma△

- Frontal Absence Seizures: Clinical and EEG Analysis of Four Cases

- Expression of miRNA-140 in Chondrocytes and Synovial Fluid of Knee Joints in Patients with Osteoarthritis△

- Effects of Lianhua Qingwen on Pulmonary Oxidative Lesions Induced by Fine Particulates (PM2.5) in Rats

- The Effect of Sleep Deprivation on Coronary Heart Disease△

- Uterine Artery Embolization for Management of Primary Postpartum Hemorrhage Associated with Placenta Accreta