Evaluation of polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells in cervical sample as a diagnostic technique for detection of subclinical endometritis in dairy cattle

Mohammad Rahim Ahmadi, Ali Kadivar, Mahmood Vatankhah

1Department of Clinical Science, School of Veterinary Medicine, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran

2Research Institute of Animal Embryo Technology, Shahrekord University, Shahrekord, Iran

3Department of Animal Science, Agriculture and Natural Resources Research Center, Shahrekord, Iran

Evaluation of polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells in cervical sample as a diagnostic technique for detection of subclinical endometritis in dairy cattle

Mohammad Rahim Ahmadi1*, Ali Kadivar2, Mahmood Vatankhah3

1Department of Clinical Science, School of Veterinary Medicine, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran

2Research Institute of Animal Embryo Technology, Shahrekord University, Shahrekord, Iran

3Department of Animal Science, Agriculture and Natural Resources Research Center, Shahrekord, Iran

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Received 2016

Received in revised form 2016

Accepted 2016

Available online 2016

Subclinical endometritis Cervical cytology Dairy cattle

Objective: This study evaluated the cervical sampling as an easy and safe method for the diagnosis o subclinical endometritis in dairy cattle. Methods: One hundred ninety seven lactating Holstein cows wer examined at 26–32 d in milk (DIM) for diagnosis of endometritis. Differential cellular counts were als made from stained smears of the cervical mucosa. Using the Receiver/Response Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, presence of > 17.5% polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells was calculated for detection o subclinical endometritis with sensitivity and specificity of 56.5% and 83.3% respectively. Results: Cow with subclinical endometritis had significantly more open days and all service conception rate than norma cows. The results of survival analysis showed that normal cows became pregnant at a significantly faste rate than cows with subclinical endometritis. Conclusions: The results of the present study introduced th cervical smear sampling as an easy and suitable method for diagnosis of subclinical endometritis in dair cattle.

1. Introduction

Nearly all cows experience some degree of endometrial inflammation in early postpartum that is associated with normal involution; however, the accurate identification of truly diseased cows for administration of appropriate treatment is so important [1]. Endometritis is defined as inflammation limited to the endometrium occurring at least 21 d after calving without signs of systemic illness. Observation of purulent discharge on the tail, detection of purulent material in the vagina by vaginoscopy and detection of an enlarged uterine horn following transrectal palpation of the uterus are some of the techniques that are used for detection of endometritis in cattle [2]. In new classification, endometritis has been sub-divided into clinical and subclinical categories [3]. Clinical endometritis is defined as purulent or mucopurulent uterine discharge present after 21 or 26 d postpartum. Subclinical endometritis can be defined as endometrial inflammation of the uterus in the absence of purulent material in the vagina [1]. Despite the absence of purulent discharge, the severity of the disease is still considered sufficient to impair reproductive performance. Animals with subclinical disease have more days open, take longer to conceive, have lower conception rates and are culled more than normal animals. Typical conception rates are half that of normal animals [1,4]. Several techniques such as uterine biopsy [5], uterine lavage [6], cytobrush [7] and a guarded cotton swab [8] have been used for the diagnosis of the subclinical endometritis. Collection of endometrial and inflammatory cells is the base of all these techniques. Among these, uterine biopsy is the most invasive technique and can impair subsequent reproduction in biopsied cows [9]. Cytobrush and uterine lavage are less harmful techniques for the endometrium than the uterine biopsy; however, both techniques are time consuming. The fluid that is used for uterine lavage can be irritant and causes a 17% failure in attempts to recover fluid [7]. It has been suggested that sampling by uterine lavage can cause a tendency for lower first-service conception in primiparous cows [10].

Yavari et al. showed that the neutrophil percentage in cervical mucosa and uterine fluid of the cows affected by Arcanobacterium pyogenes and clinical signs of purulent uterine discharge were significantly higher than unaffected cows. The result of their study did not show any significant differences between neutrophils percentages of cervical mucosa and uterine fluid smear in cows with three classifications of clinical endometritis [11]. These authors also investigated there were no significant differences in cell densities between uterine and cervical mucosa in genital tracts of slaughtered cows affected with either acute or chronic endometritis [12]. These

findings suggest that there is a reasonable correlation between uterine and cervical cytology. As regards cervical sampling, it is easier, requires less time and it is not irritant for uterine endometrium, it could possibly be a convenient alternative for uterine lavage and cytobrush in subclinical endometritis diagnosis.

The objective of this study was to evaluate cervical sampling as an easy and safe method for the diagnosis of subclinical endometritis in dairy cattle.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals and herd

The study was conducted on 197 lactating Holstein cows in a large commercial dairy herd in Shiraz, Iran (longitude 052 36’E and latitude 29 33’N). The area has a warm climate with four distinct seasons, with peak summer temperatures reaching above 40 C and a winter minimum temperature below freezing. Throughout the year, cows were housed in a tie-stall barn with straw bedding. Cows were group fed a total mixed ration to meet production requirements.

2.2. Clinical examinations

Cows were examined at 26–32 d in milk (DIM) for diagnosis of clinical endometritis. During the examination, cows were first inspected for the presence of fresh discharge on the vulva, perineum or tail. If discharge was not visible externally, the cows were examined through the vagina. The cow’s vulva was thoroughly cleaned with a dry paper towel and a clean, lubricated and gloved hand was inserted through the vulva. In each cow, the lateral, dorsal and ventral walls of the vagina were palpated, and the mucus contents of the vagina withdrawn manually for evaluation [2]. The vaginal mucus was assessed for color and proportion of pus. Cows with abnormal uterine discharge (discharge with flecks of pus or mucopurrulent discharge) were diagnosed with clinical endometritis. Cows were also examined with transrectal ultrasonography (real time B-mode linear array scanner with a 5 MHz transducer, 500 V, Ami, Canada) with a 5 MHz linear-array transducer for presence of any amount of fluid in uterus.

Differential cellular counts were made from stained smears of the cervical mucosa. A clean 50 cm plastic uterine pipette was used for collection of cytological samples. The vulva was washed with antiseptic solution. The plastic uterine pipette was fixed at external os of the cervix by rectovaginal method. Cervical mucosa aspirated by 50 mL syringe. Once the sample had been taken, the mucosa was rolled on glass slides and air-dried and differential cellular count was carried out on Giemsa-stained smear of the mucosa. The cytology slides were fixed by methanol for five minutes then put on the Giemsa stain for 20 min and finally washed in distilled water and dried. Smear slides were evaluated by light microscope. At least 100–200 cells were counted in 20 microscopic fields (×900). The counted cells were epithelial cells and neutrophils.

2.3. Calculation of reproductive parameters

Parameters assessed for reproductive performance were interval from calving to pregnancy (days open, DO) (the mean number of days from calving to conception among the cows that became pregnant within 210 d postpartum), interval from calving to first service, all service conception rate (the number of cows that conceived within 210 d postpartum, divided by the number of all given services, multiplied by 100) and first service conception rate (the number of cows conceived with first AI within 210 d postpartum, divided by total number of cows that received AI, multiplied by 100).

2.4. Statistical analyses

A Receiver/Response Operating Characteristics (ROC) curve was plotted to determine the cut off percentage PMN for detection of subclinical endometritis using the visible abnormal uterine discharge as gold standard test for endometritis. Based on calculated cut off PMN in cervical discharge, cows were divided into two groups: with and without subclinical endometritis. Four indices of reproductive performance (days open, calving to first service, all service conception rate and first service conception rate) were compared between these two groups using the t-test of the SAS 9.2 (Statistical analysis system package, Cary, NC, USA: SAS Institute, Inc 2005). Days open and days to first service were presented as least square means and the accompanying standard error of the mean. First service and all service conception rates were presented as percent. Significance was established at P < 0.05. The sensitivity and specificity values for the cervical cytology diagnostic test were calculated when it was used to predict pregnancy status at 100 d postpartum. To verify the assumption of proportional hazards of pregnancy for cows with and without subclinical endometritis, the Kaplan–Meier survival functions were estimated for each group using the LIFE TEST procedure in SAS. The number of open cows was plotted against the time to pregnancy.

3. Results

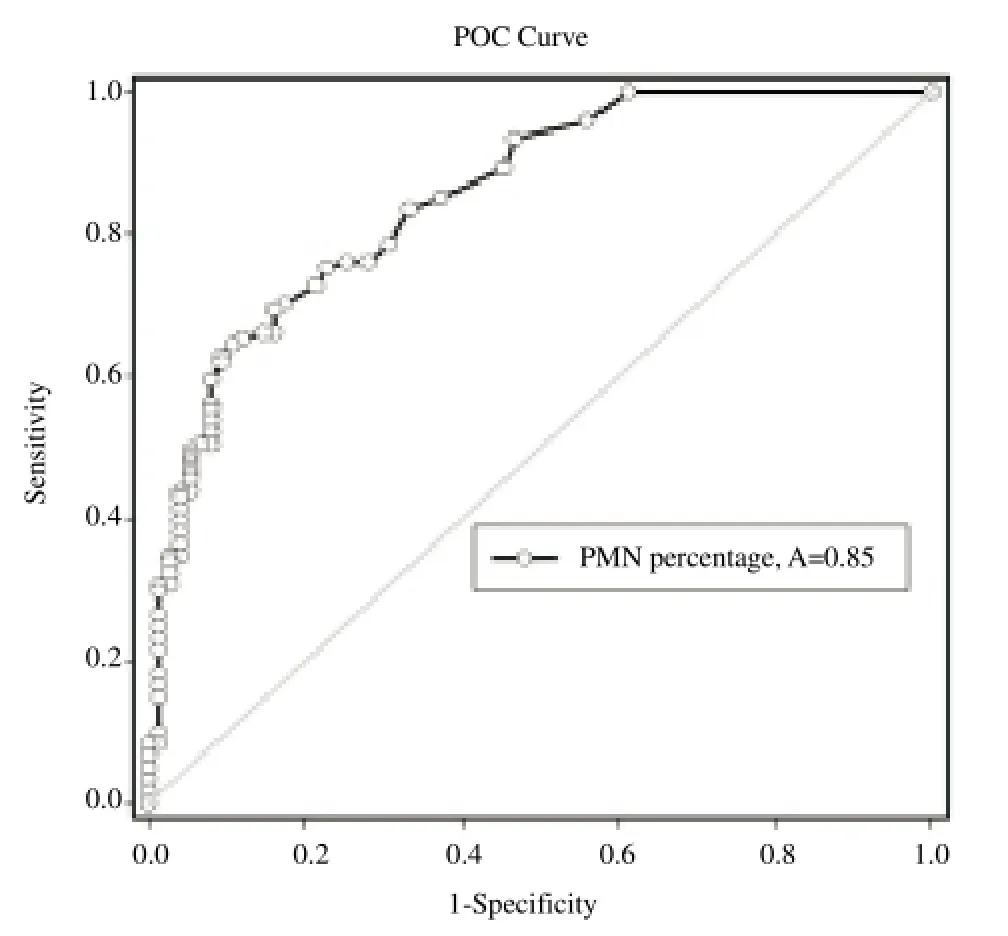

The study was conducted on 197 cows at 26–32 d after calving. Of these 197 cows, 121 (61.4%) cows were observed with abnormal uterine discharge and were diagnosed as clinical endometritis. All of the cervical cytology slides were readable and assessed successfully. Mean PMN percentage was 18.8% (range, 0%–95%). A Receiver/ Response Operating Characteristics (ROC) curve was plotted using the sensitivity and specificity for each possible percentage PMN at 26–32 d postpartum for detection of subclinical endometritis. In this analysis, presence of abnormal uterine discharge was used as gold standard test for endometritis. The ROC curve identified >17.5% PMN at 26–32 d postpartum as the cut point (Figure 1). Dot histogram for the data associated with the ROC curves is shown in Figure 2. The optimal cutoff value for the test is computed and represented as a horizontal line across the two dot histograms for each group (Figure 2). With this definition 21 (10.6%) cows were diagnosed as cows with subclinical endometritis. Using the 17.5% PMN cut-off and presence of abnormal uterine discharge as the reference diagnostic test, the sensitivity and specificity values for cervical cytology test were 64.4% and 89.3%, respectively. The sensitivity and specificity values for the cervical cytology diagnostic test when it was used to predict pregnancy status at 100 d postpartum was 56.5% and 83.3%, respectively.

Figure 1. Receiver/response operator characteristic curve to estimate threshold percentage PMN in cervical sample at 26–32 d after calving.A: ROC curve area.

Figure 2. Dot histogram pair for the subclinical endometritis diagnosis test. The horizontal line shows the calculated optimal cutoff value.

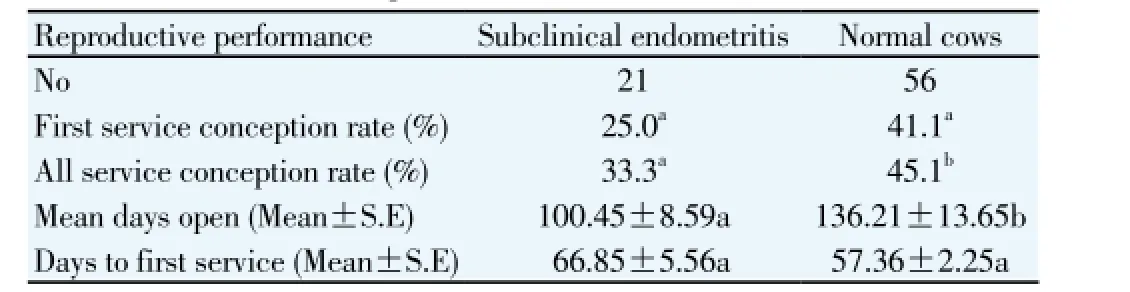

To evaluate the impact of subclinical endometritis on reproductive performance all cows with abnormal uterine discharge were excluded. Cows with clear discharge (which were considered as clean cows at 26–32 d postpartum) were divided into two groups: cows with > 17.5 and < 17.5 PMN percentage in cervical discharge. The reproductive performance of cows with subclinical endometritis compared to normal cows is described in Table 1. All service conception rate was significantly higher in cows with subclinical endometritis than normal cows. The mean days open was also significantly higher in cows with subclinical endometritis than normal cows. Mean days to first service and first service conception rate was higher in cows with subclinical endometritis than normal cows; however, this difference was not significant.

Table 1 Reproductive performance of cows with subclinical endometritis and normal cows at 26–32 d after calving.

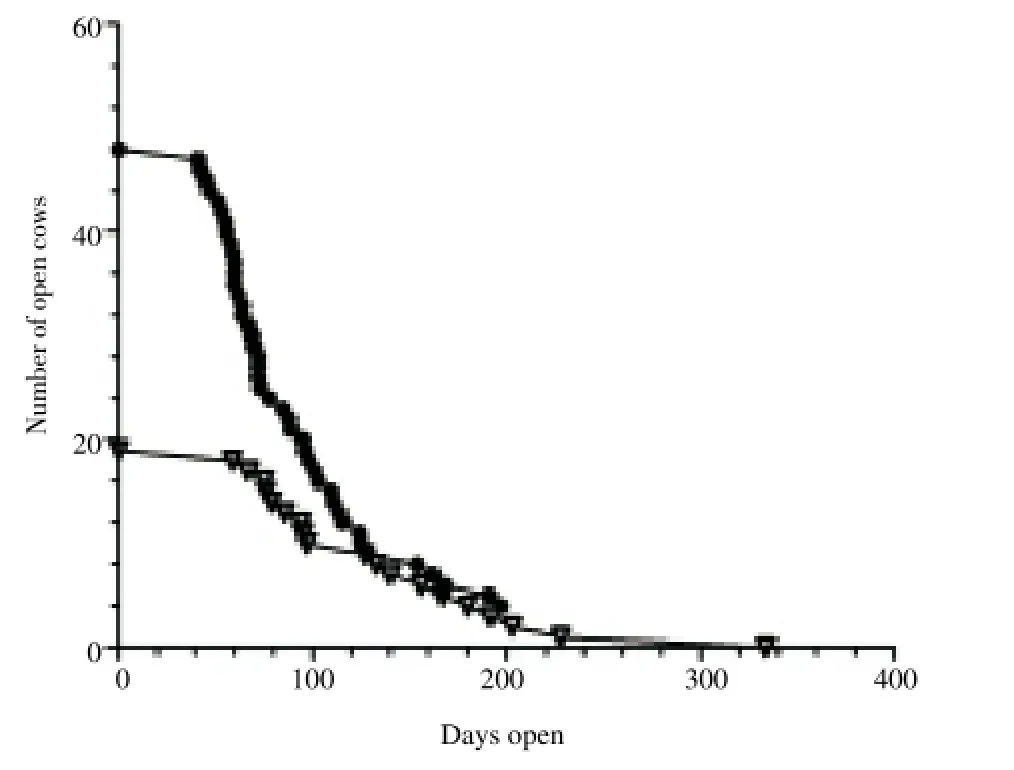

Figure 3 shows the relationship of number of open cows and days open for cows with subclinical endometritis and normal cows at 26–32 d after calving. Normal cows became pregnant at a faster rate than cows with subclinical endometritis (P < 0.05).

Figure 3. Survival curve: relationship of number of open cows and days open for cows with subclinical endometritis (white rectangles) and normal cows (black circles) at 26–32 d after calving

4. Discussion

Healthy uterine environment is the key to optimal fertility in dairy herds. Regeneration of damaged endometrial tissue in cattle takes occurred during the 2nd to 4th week after parturition so that there is little evidence of the previous pregnancy approximately 6 weeks after calving. In about half of the high producing dairy cows these normal events do not occur, so they don’t have “clean uterus” at 4th week postpartum examination [13]. These are categorized as cows with clinical endometritis. Some of the clinically healthy cows have degrees of endometrial inflammation, which is characterized by the proportion of PMN cells in a cytological sample of endometrium [4]. The prevalence of subclinical endometritis in the current study was 10.6%, which was lower than in other studies on subclinical endometritis with prevalence of 13%–94% [1,14]. The difference in prevalence of subclinical endometritis in different studies depends on the diagnostic method and the time postpartum when the examination is performed. Furthermore, there is no consensus about the proportion of PMN that defines subclinical endometritis [3,6].

In the current study, for pregnancy by 100 d, the diagnostic criteria of subclinical endometritis had a sensitivity of 56% and a specificity of 83%. The sensitivity and specificity obtained for cervical cytology diagnostic test in the present study is quite comparable with the results of other studies in this field. Kasimanickam et al. reported that > 18% PMN at 20–33 d postpartum without presence

of clinical endometritis was associated with an impairment of reproductive performance [4]. They used the cytobrush technique and reported a sensitivity of 36% and a specificity of 94% when their results were evaluated in relation to pregnancy status at 132 d postpartum. Barlund et al. used five diagnostic techniques for detection of endometritis between 28 and 41 d postpartum in dairy cattle [6]. Cytobrush cytology was the most reliable method for diagnosing endometritis in their study. Using 8% PMN cutoff, this method had the sensitivity and specificity of 12% and 89% in relation to pregnancy status at 150 d postpartum. LeBlanc et al. used the diagnostic criteria of presence of vaginal discharge and cervix diameter > 7.5 cm and determined a sensitivity of 20% and specificity of 88% for pregnancy by 120 d after calving [15]. Bonnett et al. reported a sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 77% for pregnancy by 120 d in milk with uterine biopsy [16].

Diagnostic tests require dichotomization of results and a gold standard to achieve high sensitivity and specificity [17]. As the results of the present and other mentioned studies show, the sensitivity of diagnostic tests for endometritis are less than 100% when measured against reproductive performance. This is because of numerous independent and unaccountable reasons for which cows fail to become pregnant. Furthermore, the spontaneous resolution of uterine disease may lead to false positive results. However, the specificity of cervical cytology test was generally higher in this study, which indicates a higher proportion of subclinical endometritis cows were diagnosed correctly.

Using cervical sampling for diagnosis of subclinical endometritis, in addition to being easier than the two other common methods (cytobrush and uterine lumen flushing) reduces the chance of damage to cells. Barlund et al. have mentioned two reasons for cellular damage in lavage method: 1- variable reported range of the PH of commercially available saline products (ranging from 4.7 to 7.0 [18]. It may negatively affect the integrity of the cells. 2-Centrifugation process. They have noted even in a conventional centrifuge program (for example, 600×g for 15 min) some small amount of cellular damage may occur [6]. Uterine lavage is also a time consuming process and 17% failure in attempts to recover lavage fluid is reported [19]. However, unlike the cytobrush technique, the required materials for cervical sampling are available in most veterinary practices.

In conclusion, cytological evaluation of cervical smear is a suitable method for diagnosis of subclinical endometritis, planning for treatment, and prognosis of fertility in dairy cows. With an acceptable sensitivity and specificity it can be an alternative test for routine subclinical endometritis diagnostic tests such as cytobrush and uterine lavage.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Farzis Meat and Milk Company (Shiraz, Iran) for the use of their herd and facilities.

[1] Gilbert RO, Shin ST, Guard CL, Erb HN, Frajblat M. Prevalence of endometritis and its effects on reproductive performance of dairy cows. Theriogenology 2005; 64: 1879-1888.

[2] Sheldon IM, Noakes DE, Rycroft AN, Dobson H. Effect of postpartum manual examination of the vagina on uterine bacterial contamination in cows. Vet Rec 2002; 151: 531-534.

[3] Sheldon IM, Lewis GS, LeBlanc S, Gilbert RO. Defining postpartum uterine disease in cattle. Theriogenology 2006; 65: 1516-1530.

[4] Kasimanickam R, Duffield TF, Foster RA, Gartley CJ, Leslie KE, Walton JS, et al. Endometrial cytology and ultrasonography for the detection of subclinical endometritis in postpartum dairy cows. Theriogenology 2004; 62: 9-23.

[5] Chapwanya A, Meade KG, Narciandi F, Stanley P, Mee JF, Doherty ML, et al. Endometrial biopsy: a valuable clinical and research tool in bovine reproduction. Theriogenology 2010; 73: 988-994.

[6] Barlund CS, Carruthers TD, Waldner CL, Palmer CW. A comparison of diagnostic techniques for postpartum endometritis in dairy cattle. Theriogenology 2008; 69: 714-723.

[7] Kasimanickam R, Duffield TF, Foster RA, Gartley CJ, Leslie KE, Walton JS, et al. The effect of a single administration of cephapirin or cloprostenol on the reproductive performance of dairy cows with subclinical endometritis. Theriogenology 2005; 63: 818-830.

[8] Cocchia N, Paciello O, Auletta L, Uccello V, Silvestro L, Mallardo K, et al. Comparison of the cytobrush, cottonswab, and low-volume uterine flush techniques to evaluate endometrial cytology for diagnosing endometritis in chronically infertile mares. Theriogenology 2012; 77: 89-98.

[9] Etherington WG, Martin SW, Bonnett B, Johnson WH, Miller RB, Savage NC, et al. Reproductive performance of dairy cows following treatment with cloprostenol 26 and/or 40 days postpartum: A field trial. Theriogenology 1988; 29: 565-575.

[10] Cheong SH, Nydam DV, Galvão KN, Crosier BM, Gilbert RO. Effects of diagnostic low-volume uterine lavage shortly before first service on reproductive performance, culling and milk production. Theriogenology 2012; 77: 1217-1222.

[11] Yavari M, Haghkhah M, Ahmadi M, Gheisari H, Nazifi S. Comparison of cervical and uterine cytology between different classification of postpartum endometritis and bacterial isolates in Holstein dairy cows. Int J Dairy Sci 2009; 4: 19-26.

[12] Ahmadi MR, Tafti AK, Nazifi S, Ghaisari HR. The comparative evaluation of uterine and cervical mucosa cytology with endometrial histopathology in cows. Comp Clin Pathol 2005; 14: 90-94.

[13] Hoedemaker M, Prange D, Gundelach Y. Body condition change anteand postpartum, health and reproductive performance in German Holstein cows. Reprod Domes Anim 2009; 44: 167-173.

[14] Kaufmann TB, Drillich M, Tenhagen BA, Forderung D, Heuwieser W. Prevalence of bovine subclinical endometritis 4h after insemination and its effects on first service conception rate. Theriogenology 2009; 71: 385-391.

[15] LeBlanc SJ, Duffield TF, Leslie KE, Bateman KG, Keefe GP, Walton JS, et al. Defining and diagnosing postpartum clinical endometritis and its impact on reproductive performance in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 2002; 85: 2223-2236.

[16] Bonnett BN, Wayne Martin S, Meek AH. Associations of clinical findings, bacteriological and histological results of endometrial biopsy with reproductive performance of postpartum dairy cows. Prev Vet Med 1993; 15: 205-220.

[17] Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P. Clinical epidemiology: A basic science for clinical medicine. New York: Little Brown and Co; 1991, p. 51-68.

[18] Vanderwall DK, Woods GL. Effect on fertility of uterine lavage performed immediately prior to insemination in mares. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2003; 222: 1108-1110.

[19] Kasimanickam R, Duffield TF, Foster RA, Gartley CJ, Leslie KE, Walton JS, et al. A comparison of the cytobrush and uterine lavage techniques to evaluate endometrial cytology in clinically normal postpartum dairy cows. Can Vet J 2005; 46: 255-259.

ment heading

10.1016/j.apjr.2016.06.011

*Corresponding author: Mohammad Rahim Ahmadi, Departments of Clinical Sciences, School of Veterinary Medicine, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran, Postal Code: 7144169155.

Tel: +987136138708

Fax: +987132286940

E-mail: ahmadi1335@gmail.com

Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction2016年4期

Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction2016年4期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction的其它文章

- Effects of pomegranate juice in Tris-based extender on cattle semen quality after chilling and cryopreservation

- Relationship between gestational age and transabdominal ultrasonographic measurements of fetus and uterus during the 2nd and 3rd trimester of gestation in cows

- Evaluation of the academic achievement of rural versus urban undergraduate medical students in pharmacology examinations

- The relationship between trace mineral concentrations of amniotic fluid with placenta traits in the pregnancy toxemia Ghezel ewes

- In vitro polyembryony induction on a critically endangered fern, Pteris tripartita Sw.

- Spontaneous pregnancy after vaginoplasty in a patient presenting a congenital vaginal aplasia