动态影像创作方式的演变与发展

——从实验电影、录像艺术到数字动态影像

岳明慧 郝 锐 文 岳中生 译/

动态影像创作方式的演变与发展

——从实验电影、录像艺术到数字动态影像

岳明慧 郝 锐 文 岳中生 译/

20世纪的先锋派把以技术为基础的艺术(从摄影到电影,再到录像,直到虚拟现实以及介于其间更多的其他形式)引入到了曾经被工程师和技术人员占据的领域。从早期的实验电影、录像艺术到数字动态影像,他们把所有的新材料、新媒介都引入了艺术,为艺术创作带来了更大的自由。本文试图通过梳理动态影像的发展脉络及各阶段创作方式的演变与发展,来探讨动态影像这门艺术在新的技术语境中如何以不同的方式不断再现、更新和发展,为艺术创作提供更自由、更丰富、更多元的可能性。

创作方式;动态影像;实验电影;录像艺术;数字动态影像

梅雅•黛伦 午后的迷惘 1943年Maya Deren, Meshes of the Afternoon, 1943

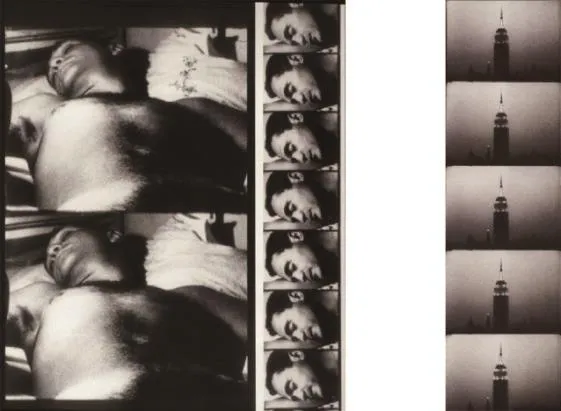

安迪•沃霍尔 沉睡(左),帝国大厦(右)Andy Warhol, Sleep (left),Empire (right)

维托•阿孔奇 主题歌 1973年Vito Acconci, Theme Song, 1973

一、实验电影

1.实验电影的反叙事性

当我们谈论实验电影的时候,它经常被说成是“先锋的”。事实上,在“实验电影”一词当中的“实验”就很好地说明了这类电影的明显特征,它没有特定的表达框架,没有传统的故事情节,而是有极强的“反叙事性”。它用非常规的叙事顺序反对电影的叙事,去进行一种革命性的探索,更多的是用抽象的镜头、片段去强调电影的表现性,而不去叙述故事,进而去表现远离现实的抽象化和潜意识化的倾向性,它倾向于对梦幻、恐惧、欲望的表达,更注重象征化与心理化的表现。

琼•乔纳斯 左侧,右侧 1972年Joan Jonas, Left Side, Right Side, 1972

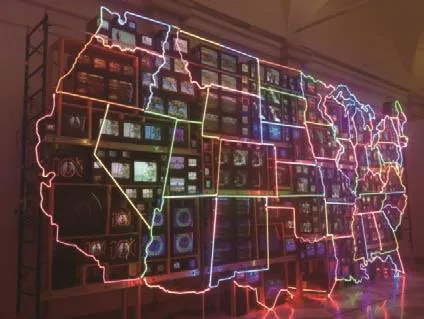

白南准 电子高速公路 1995年NamJune Paik, Electronic Superhighway, 1995

保罗•菲佛 约翰3:16 2000年Paul Pfeiffer, John 3: 16, 2000

2.出现的背景

(1)实验电影起源于欧洲的“先锋派”电影。第一次世界大战摧毁了法、德的电影企业,只有美国电影得到发展,逐渐形成了称霸世界以商业电影为主的电影工业。欧洲电影重新崛起,不可能模仿和重复美国的电影模式,因此他们只有在艺术上创新,才能与美国的商业电影抗衡,并建立自己的电影艺术。

(2)文化上,19世纪末20世纪初,在欧洲逐渐兴起的现代主义文艺思潮进入电影。现代哲学中的存在主义哲学,强调人的存在本质和人的自由选择;现代科学的相对论,改变了传统的时空观念;弗洛伊德的无意识心理等学说都为实验电影提供了文化的动机和背景,影响了实验电影的创作。

3.部分反叙事性倾向的实验电影

(1)《幕间休息》1969年

雷内•克莱尔(René Clair)导演的一部没有故事情节的先锋派实验作品《幕间休息》,以让人匪夷所思的情节完全摒弃了传统的具有逻辑性的叙事方式,而是用镜头之间的具有相似性的视觉造型上的联系来代替。影片的前半部分是由许多并不相关的片段组成,后半部分是一个比较连续的插曲。影片一开场的开炮,然后便是下棋、射击、葬礼、复活的镜头,直至最后消失闭幕,这里面的每一件事情都以闹剧的方式滑稽地收尾。①克莱尔用这种反叙事性的方式,将没有必然因果联系的片段剪辑在一起,抨击了资产阶级的习俗、风尚、文化和礼仪,庄严的葬礼变成了一场疯狂滑稽的追逐,体现了战后青年一代愤世嫉俗的精神状态。

(2)《午后的迷惘》1943年

梅雅•黛伦(Maya Deren)的《午后的迷惘》用真实和幻觉互相交织的方式拍摄了自己,这些镜头的剪辑违背常理,影片由一个女人午后的梦境构成,这个梦境出现了5次,并且每次梦境的开头相同,但每一次都采用了不同的视角和情节表现同一件事情,由此导致不同的结局。她通过不同于主流电影的创作方式,用恍惚晃动的镜头,不安的动作,成功地表现了多个层次的自我以及女性的自我探寻和挖掘。

4.意义何在

面对战后残酷的社会现实,许多艺术家开始采取逃避现实的态度,开始从外部世界返回到内心,曲折地表达艺术家对现实的愤懑不满和内心的苦闷焦虑。与其说实验电影在寻找形式上的反叙事性、纯粹性,不如说它们是在寻找一种新的语言表达。它们表现了远离现实的抽象化和潜意识化的倾向,强调影像本身对于内心精神世界的表现,认为电影是对世界和自我认识的表现和感受,是对世界及人的本性的思考,是对人生经验和审美经验的一种超越。这些都表明它是一种自觉的艺术样式,不同于电影诞生初期的杂耍性质。

实验电影用生活流手法(用事件的无逻辑组合)以及意识流手法(非理性的意识活动),来代替或打乱逻辑的情节结构。用非传统的碎片式镜头的拼接来破坏传统的技法。它是现代社会在人的精神生活和艺术生活中的反映,让人在表现、感官等方面更多地思考社会和思考人性,回归到自己的内心,对后来的录像艺术乃至新媒体艺术都产生了深远影响。

二、录像艺术

1.录像艺术的客观记录性

到了20世纪60年代,录像艺术产生。虽然它同样是反对叙事,但是与实验电影通过胶片拍摄演员的演绎来表现内心世界不同,录像最初的冲动是把目光所及的一切东西都录下来,它不像实验电影那样精心地去编排、拍摄影片,对每个镜头精益求精,而是去客观地记录现实本身。此时屏幕上的影像更多地依赖于我们生活中可见的客观事物,只是艺术家通过高度个人化的方式利用摄像机把它们记录下来,再通过个人化的方式进行不同的呈现,以此来表达他们的观看方法和个人体验。并以此来说明世界本身并不仅仅是客观现实,它还包含意识的存在。

2.出现的背景

(1)1925年,英国工程师约翰•洛吉•贝尔德发明了电视机,电视用电波信号的方法即时传送活动的视觉图像。这样,过去只能在电影院里观看世界各地图像的方式,可以有选择地进入普通家庭。到1953年,已经有三分之二的美国家庭拥有了电视。到1960年更是达到了百分之九十,电视已经到了完全商业化的程度。美国人每天看电视长达7个小时,新的消费社会开始形成,广告巨头激发并保持着电视消费增长的势头。1965年,索尼公司开发了小型便携式摄像机以及相匹配的影像编辑系统。电视机和摄像机的逐渐普及,减小了过去因购买胶片的巨额费用所导致的创作局限,许多并不专业的视频爱好者和普通人也能够运用最新的技术进行影像的记录和创作,一种不同于电视和电影制作的个人写作成为可能。这对以电视等为展示工具的视频艺术的媒介革命起到了很大的作用。

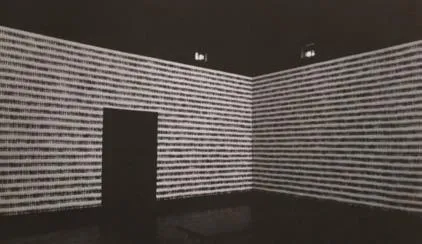

米歇•鲁芙娜 余下时间 2003年Michal Rovner, Time Left, 2003

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Under Scan, 2005

(2)此外,这个年代(20世纪60年代),是一个社会大变革的时代。当时许多欧美国家的青年人开始秉持着完全与其父辈们相反的价值观,学生的政治抗议活动、女权主义运动和性革命等,都是有助于录像艺术产生的文化背景。

(3)1965年,韩国出生的艺术家白南准在纽约买了一部portapak摄像机,随后拍摄了教皇保罗六世访问纽约造成的交通堵塞。几个小时后,便在索霍区一家咖啡馆里播放了该视频。这天被看作是录像艺术的诞生日。

3.录像艺术的观念性和它与表演、装置的结合

确实,“记录”是录像实践功能最直白的特征。早期的录像艺术确实把它作为现实的客观记录,这也充分体现了录像艺术“录(记录)”的功能。但如果录像艺术仅仅作为一种记录的方法,它就不可能成为一种真正的具有独立意义的艺术形态,只能是作为被动“记录”的机械工具。但是艺术家发现了“录像”作为新的艺术媒介创造艺术表现的手段,在录像艺术“记录”的基础之上,将之与表演和装置相结合,进而去表达自己的观点。

(1)录像艺术的观念性

20世纪60年代的录像艺术观念,受当时媒体时代的刺激(电视对大众日常生活的控制),艺术家们开始批判、反抗电视节目这种主流媒体的陈词滥调。因此艺术家将录像当成新的语言和方法,借此来表达他们的创作意念。他们作品的主题经常就是“反电视”,因而录像艺术在诞生之初其观念性就十分明显。②和那些跟在教皇后面拍摄新闻的记者不同,白南准生产的是一种粗糙的、非商业化的产品,是带有个人观点的表达。白南准发现了录像作为一种新媒介的记录功能,更是利用这一新媒介进行个人观点的呈现。白南准曾这样说:“电视已经占领了我们所有的生活,现在我们要回击。”

20世纪60年代中期,安迪•沃霍尔(Andy Warhol)拥有了他的第一部手持摄录机,他在1965年用它所拍摄的《工厂日记》,记录了工厂里的各种活动,包括人们的日常生活,如吃饭、睡觉或对着摄录机说话等等。他的作品《沉睡》,更是用摄像机拍一个男人睡觉的一分一秒,长达六个小时,这恢复了摄影机的原始功能——记录。其1964年的作品《帝国大厦》,用单一的固定机位拍摄了纽约帝国大厦从傍晚到清晨八个小时间的变化。他通过这样真实时间的一致的拍摄,恢复了摄像机的原始记录功能。

(2)录像艺术与表演的结合

录像艺术受表演艺术的影响,早期的录像艺术在某个层面上可以看作是表演的单纯记录,或后来被称为“表演性的行为”。他们将相机对准自己身体的局部并就这些部位在“人”的范畴内意味着什么提出疑问。

维托•阿孔奇(Vito Acconci)在1971年摄制的几部单信道黑白录像作品,将摄像机对准自己,把媒体引向自身,直接对观众说话,以探索观众(或窥淫癖者)和被观看主体之间的关系。在其作品《主题歌》(1973)中,他躺在黑白条纹沙发前的地板上,占整个画面2/3的面部和观众对话:“我要你进来。”无休止地邀请观众和他一起加入到镜头里面去。他从一个男性的视角揭示了电视图像给观众带来的虚假联系,并且反映出了电视媒体给人的错觉——亲和性。

琼•乔纳斯(Joan Jonas)的作品《左侧,右侧》,用一种更古怪的方式摆弄摄像机和镜子,她让观众在看到镜子里的反向图像时一时分不清左边和右边。为了增加观众的困惑,她还不断故意地重复说“这是我的左边,这是我的右边”,直到观众再也无法分辨出到底哪个是她的左边,哪个是她的右边,从而打破观众和电视图像之间的联系。和阿孔奇相同,乔纳斯也拍摄自己,进行表演。但是她打破常规视角,用涉及自己身体的方式创造一个引人注目的个人女性主义形象,她说:“我利用录像来拓展自己的语言,诗歌般的语言。录像对我来说,是让我能够全身心投入探索语言的一个空间元素。我可以爬进去,待在里面探索。”

(3)录像艺术与装置的结合

无论是简单的记录,还是个人的表演,看似无限的可能性和相对较低的负担能力,使得录像艺术对在媒体饱和时代成长起来的年轻艺术家越来越有吸引力。录像既是参与媒体的方法,也是对媒体过度反应的方法,同时也是一种对传达个人信息进行呈现的手段。艺术家的创作项目在物理尺寸和表现范围上已经变得更为广大,而创作的主题却越来越个人化和个性化。许多艺术家已经开始创建复杂的媒体装置了,他们可以控制的不仅是图像,而且还包括他们自己设计的在完整的环境中观看图像的背景。③

白南准的录像装置作品《电子高速公路》(1995),是在展厅中堆放了几十个显示器,看起来像一个通用数据库那样接二连三的图像,有世俗政治、自然界的核爆炸等。装置的整个外形是美国版图的缩影,即美国大陆由313台电视机装置组成,阿拉斯加24台,夏威夷每个岛1台,用钢结构制作的国界、霓虹灯、200瓦音响系统等等。白南准的这个高速公路到处是媒体文化的碎屑,但他仍然用这些闪闪发光的形象警告战争和文化上的动荡。

玛丽•卢西尔(Mary Lucier)的作品《斜屋》,是把汽车经销商改过的内部空间变成没有窗户只有显示器的石膏板房。她认为这个建筑环境是关于图像和声音的:露天的房子里面是黑暗的,电视监视器提供的是窗户上看不到的景色,因而也能更加深入到人们的灵魂中去。艺术家安德里安•派普(Adrian Piper)在其作品《像啥就是啥#3》(1991)中,将显示器镶嵌在白色盒子的每个侧面中,显示器的内容是从不同角度显示黑人的脑袋,并且视频内容是黑人对种族歧视愤怒的反驳:“我不懒”“我不庸俗”“我不色”等等。这里我们可以看到派普的多重身份:知识的、艺术的、种族的和个人的。

4.意义何在

录像最初的冲动是把目光所及的一切东西都录下来,它不像实验电影那样精心地去编排、拍摄影片,对每个镜头精益求精,而是去客观地记录现实本身,再由艺术家进行编排。此时屏幕上的影像更多地依赖于我们生活中可见的客观事物,艺术家通过高度个人化的方式利用摄像机把它们记录下来,再通过个人化的方式进行不同的呈现,去回击图像的泛滥和商业化,进而带来了新的观看方法和个人体验。作为20世纪60年代前卫的影像艺术,在动态影像的范畴内,它对影像语言进行的改造有着领头羊的作用。录像艺术与表演、装置等结合这一不局限于创作形式的宽容的创作姿态,对于后来的数字影像创作有很大的影响。随着数字技术的应用,录像艺术既存在于更广泛的媒体文化中,又游离之外,这种处境上的矛盾越来越尖锐,录像艺术家也必须定义一个独特的艺术空间,去体验时代精神上更大的自由和空间,在那里,叙述、感知和对视觉的期望都将被重新洗牌。④

三、数字动态影像

1.数字技术对影像的重新编码

新的数字动态影像艺术在发展中远远超出了当初录像艺术作为呈现和记录手段的含义,而是成为一种以数字动态影像为核心媒介载体的多种影像处理和装置环境综合使用的影像艺术。它对图像的结构、叙事话语系统重新由数字技术进行编码,影像叙事也好,非叙事也好,它都是以超链接的媒体整合方式——非线性编辑的各种拼贴手法,及录像装置的立体拼贴和互动艺术对观者经验的开放,最后落实成多媒体艺术的链接方式——为观者提供了非线性的审美体验。⑤数字技术的应用带来的新能力给图像以无限的伸展性,采用数字技术的艺术家现在能够引入的新形式是“创作”,而不是像从前那样机械地去记录客观现实。以前,尽管图像可以在电影中被编辑或能够用蒙太奇手法进行再创作纳入其他图像,但一旦转移到数字语言,那么图像中的每个元素都可以被计算机所修改。图像在计算机里就是无数个信息,而所有的信息都可以被操作。

在当今的影像展览中,“录像艺术”这一概念已经不能包含现今所有的动态影像作品。首先是以非摄像机非录制方式创作的影像作品,例如,由Maya、After effect或其他电脑软件绘制的虚拟影像。利用电脑的数字技术的后期软件可以随意对数字影像素材进行剪辑和处理,非线性的编辑方式取代了从前的线性编辑方式。网络这一全新的传播平台也给作品带来了实时的互动性。如此一来,数字动态影像在当今这个新的技术语境当中在一定程度上扩展了“录像艺术”这个词本身所不具备的特征。

2.出现的背景

随着科技的发展,特别是计算机数字影像处理、数字编辑和虚拟影像技术以及网络和互动技术的运用,不仅给人们的物质生产带来巨大的革新,也给人的思维方式带来了新的突破。就是在这样一个前提下,数字影像出现并得以发展。当然,这之中还有人们对于传统录像艺术视觉感官上的审美疲劳。运用这种艺术和技术的联盟,影像技术变得更加易于掌握和使用,材料本身对于艺术家想法的限制逐步消失,艺术家在创作作品时对于媒介技术的应用有了比以往更大的自由,从而也带来了更大的创作激情。图像不再孤独,而是相互关联的,不再是艺术中只有唯一的图像,如今已经是无数的图像,以复合方式重组观众眼睛的自然振动。⑥

3.数字动态影像作品

(1)重新定义动态影像的叙事

法国艺术家皮埃尔•于热(Pierre Huyghe)的作品《再造》(1995)重演了艾尔弗雷德•希区柯克(Alfred Hitchcock)1953年的影片《后窗》。在他的每一部作品中,于热都雇佣业余演员去完成原来电影的场景。于热说:“在拍摄之前的几个小时,演员才看到他们的台词,这正是他们的问题,口吃、忘词等所有实时的东西都在他的实时记录之中。”于热的数字录像技术利用的是电影技术(借助滑轨小车和跟踪镜头等),但不在叙事上做到完整,从而降低了电影的叙事效果,进而创造了观众和表演行为之间的新关系。

和于热在作品处理上有相似亲和力的是英国艺术家道格拉斯•戈登(Douglas Gordon)1993年的作品《24小时惊魂记》。它是把希区柯克的恐怖电影《惊魂记》以每秒两帧的速度重新进行播放,他并没有对原来电影的叙事内容进行改变,而是利用数字后期技术,将其变为无声,并将整个电影从原来的109分钟变成1440分钟,也就是整整24小时。这些放慢的镜头,如同一张张照片一样非常缓慢地重现在我们的面前,而且这些画面又似曾相识。在被他延迟拉长的时间里,每个细节都显露无疑,原来那些令人恐惧的镜头在这样缓慢的进程中变得不再恐怖,每个镜头、每一秒钟似乎都产生了新的意义。

(2)数字动态影像的非叙事性

美国艺术家保罗•菲佛(Paul Pfeiffer)利用后期制作数字编辑技术,对拍摄的视频进行重新创造和定义。在《约翰3:16》(2000)中,艺术家将五千帧的投篮动作利用数字技术进行修改,并重新给他们定位成以黑人男性为偶像,以此来突出篮球运动,并呈现一种沮丧的男性黑人体育玩家的表演片段。他的另外一些作品,也同样利用了数字技术进行了重新创造,例如,从观众视野中抹杀了NBA和拳击等主角。艺术家利用数字技术创造了一种新的叙事方式和新的时间概念,图像不再是孤独的、固定的,而是重组的、相互关联的、再造的,以新的复合方式重组观众眼睛的自然振动,观众观看作品的同时引发对经验的真实性怀疑,同时也面临着建立他们自己的体验和对于生活的意义。

以色列多媒体艺术家米歇•鲁芙娜(Michal Rovner)的作品经过复杂的数字编辑之后,她拍摄的任何生活对象个人特质的可识别性都削弱了。数百个小的、默默无语的、穿着简单的人充斥着她的视频。她利用数字编辑工具创作的作品《余下时间》(2003)是一个巨大的墙对墙的影像装置,成千上万的人物的大致轮廓,一排排整齐地向一个不可知的目的地游行,并伴随着嗡嗡的电子音乐声。这没有一定的故事情节叙事,是一个抽象的场景,让人联想起天启事件(又称王恭厂大爆炸,是天启六年即1626年明朝首都北京发生的一场神秘的大爆炸事件)的死囚或幸存者,又或许它只是朝圣者主动走向一个预期的宗教启示仪式,它也确实意味着太多的东西,让人在震撼当中进行思考。对于鲁芙娜来说,数字编辑工具用于表达她自己的想法。

(3)交互数字动态影像

在“交互数字动态影像”中,我们更注重作品本身的互动所带来的体验,影像越来越多地改成体验,它是一种观众直接参与作品的艺术形式,作者在创作构思的时候就已经把观众考虑进去,作为作品一个不可缺少的组成部分。通过交互的方式给观众带来体验,这就有别于传统艺术作品通过视觉被动消费和心理暗示影响观众,这时叙事或非叙事显得并不重要,重要的是观众在互动的参与当中有所体验。这些交互艺术作品大多是基于计算机控制和各种传感器,通过采集观众的行为、动作、温度甚至语言等各种数据信息,经过处理之后再反馈给观众。它在作品和观众之间构建了新的对话机制,使每位观众都能在艺术家创造的交互环境中得到自己的体验与感受,也为艺术家们提供了一种手段,让观众以积极的方式介入对社会问题的关注。

波兰艺术家塔马斯•沃里克斯基(Tamas Waliczky)在1994年的互动影像装置《道路》里玩起了视角变换游戏。当观众走近一个放置在一个长长的走廊尽头的投影屏幕时,屏幕上的图像随着观众的移动逐渐变小,从而获得反常理的体验。新情境和表达本身就能产生意义,这也直接导致了感知信息方式的变革。

拉斐尔•洛扎诺-汉莫(Rafael Lozano-Hemmer)的作品《Under Scan》(2005),则通过跟踪感应器和多重影像技术,让每位参与者都可以自己打开一个属于自己的艺术影像作品。在作品投影范围内,观众被计算机化的跟踪系统监测,这将会激活投射在他们身体阴影下的视频肖像。观众将他们“唤醒”,与之进行视觉的接触、身体的互动甚至是语言的互动。当观众走开时,肖像会最终消失。这个系统可以允许80人在1200平方米的面积内同时参与互动。每7分钟,整个项目停止和复位。跟踪系统是在一个短暂的“插曲”照明序列显示,该项目全部由计算机监控系统采用校准网格。

4.意义何在

加拿大的马歇尔•麦克卢汉(Marshall McLuhan,1911—1980)曾这样写道:“从某种意义上来说,任何一种新媒体,就是一种新语言,就是对经验施行的一种新的编码方式;这种编码方式来自新的工作习惯,完全来自集体意识。”⑦随着艺术和技术的联盟时代的到来,影像技术变得更加易于掌握和使用,材料本身对于艺术家想法的限制逐步消失,艺术家的精神观念主导着机械技术,用数字系统操控,改编原有的编码系统,利用电视、电影、录影、表演、互动等多种形式,将有关政治、社会、哲学、情感、体验的多重关联做“艺术编码”的创作,在作品中注入精神性元素,并且解译结果,使自己的精神图像展现在屏幕当中,改变现有图像、创造新图像有了更大的可能。

如今,数字动态影像已经渗透到人类生活的各个领域当中,它承载着新的影像艺术发展的方向,也将带来不同于以往的全新体验,在大数据信息化的时代里,扮演了重要的角色。在这里,价值、意义、体验,以及新的现实都将在参与中被建立起来。

四、结语

从最初的实验电影,到上世纪60、70年代的手持摄录机的录像艺术,到今天的数字动态影像,科技的发展为我们带来了艺术创作的更大自由。从最初利用胶片小心翼翼地拍摄反叙事来重视内心表达的实验电影,到利用摄像机客观记录现实,再到利用数字技术对影像进行重新编码的叙事和非叙事影像,媒介技术的不断发展为艺术家空间的扩展提供了现实的可能。在“解码”和“转换”的过程中,艺术家的个性和修养,通过对工具、科技、程序、展示设备等的不同利用,创造出具有不同个性和感染力的作品。尽管这些可以归功于技术和艺术器材的进步,但艺术的发展最终还是取决于艺术家个人的技艺和观念。所以,它应该是更受人的意识控制的艺术形式,而非是科技至上的艺术。而这种意识控制的综合方式可能就是一种试图突破传统叙事模式的新角度,从而带给人们以不同于以往的方式和角度来观看和理解世界。⑧在这个经济不断发展、商业泛滥的时代,经济体系渐渐剥夺了我们的生命体验,在这个空洞的现实中,利用多种新媒介手段,艺术家把我们的精神、感受、体验实体化,但并不是把它们作为一个具体物体的实体化,而是加入个人的精神体验和感性经验,并将这种经验载体实体化,使它承载着人类意识的温度和内在的精神,并重建一个生命体验的世界。

本文试图从动态影像的起源,从早期实验电影到录像艺术,再到现今数字动态影像,对整个过程进行梳理,探究每个阶段当中影像创作方式的不同所产生的艺术作品的不同,以及艺术家如何利用不同的创作方式对个人观念进行呈现。并在此基础之上,结合自己的影像创作实践,去探寻艺术家如何在这种新旧媒介的扩展和更迭之中作为历史存在找到适合自己的创作方式。正如前面所讨论的,本文并不是要列举出动态影像从实验电影到录像艺术、再到数字影像的变革,也不仅仅是分析它们之间更新换代的过程。而是通过一百年来媒介的扩展、创作方式的演变这一过程,关注动态影像艺术样式的长存不衰,关注它的延续、继承、改变和创新,关注它们如何在新的技术语境和媒介中不断再现、更新和发展,为艺术创作带来更自由、更丰富、更多元的可能性。在这里,价值、意义、体验,以及新的现实都将在参与中被建立起来。

注释:

①见《法国超现实主义电影概论》,载《南京师范大学文学院学报》2005年第3期。

②孙炜炜:《动态影像艺术的艺术表达及其特征解析——基于实验电影、录像艺术和新媒体影像》,载《武汉科技大学学报(社会科学版)》2013年第2期。

③[美]迈克尔•拉什:《新媒体艺术》,上海人民美术出版社,2015年。

④同上。

⑤知乎网:《如何理解影像艺术较合适?》(http://www.zhihu.com/question/36891170)。

⑥保罗•维利里奥:《视觉机器》,南京大学出版社,2014年。

⑦艺术档案网:《20世纪后期的录像艺术》,来源:美术出版艺术界,作者:迈克尔•拉什(Michael Rush),萧莎译(http://www.artda.cn/view.php?tid=5728&cid=20)。

⑧高明潞、陈小文:当代数码艺术,广西师范大学出版社,2015年。

[1]A.L.李斯.实验电影史与录像史[M].长春:吉林出版集团,2011.

[2]迈克尔•拉什.新媒体艺术[M].上海:上海人民美术出版社,2015.

[3]迈克尔•阿彻.1960年以来的艺术[M].上海:上海人民美术出版社,2015.

[4]高明潞,陈小文.当代数码艺术[C].桂林:广西师范大学出版社,2015.

[5]陈建军.新锐影像艺术[M].南京:江苏美术出版社,2007.

[6]张世君.外国电影史[M].北京:北京师范大学出版社,2014.

[7]周星.电影概论[M].北京:高等教育出版社,2004.

[8]保罗•维利里奥.视觉机器[M].南京:南京大学出版社,2014.

[9]尼古拉•布里奥.后制品[M].北京:金城出版社,2014.

[10]董冰峰,等.从电影看:当代艺术的电影痕迹与自我建构[M].北京:新星出版社,2010.

[11]E.H.贡布里希.艺术的故事[M].南宁:广西美术出版社,2014.

[12]孙炜炜.瑰丽的梦与真切的痛——影像之于东西方女性艺术家[J].理论月刊,2013(1):73—77.

[13]孙炜炜.动态影像艺术的艺术表达及其特征解析——基于实验电影、录像艺术和新媒体影像 [J].武汉科技大学学报:社会科学版,2013(2):227-232.

[14]如何理解影像艺术较合适[EB/OL]. [2016-2-21].http://www.zhihu.com/question/36891170.

本文系天津师范大学校青年基金资助(52WU1603)

岳明慧:天津师范大学美术与设计学院教师

郝 锐:天津美术学院实验艺术学院综合绘画系在读硕士研究生

岳中生:中国民航大学副教授

I. Experimental Cinema

1. Anti-narrativity

Whenever experimental cinema is spoken of, it is usually referred to as “avant-garde.” In fact, the word “experimental” can better describe its features: no de fi nite expression framework, no traditional storyline,but showing strong “anti-narrativity.” In it unconventional narrative order is employed to attempt at a revolutionary exploration. Abstract shots and footages are used to emphasize the cinema’s expressiveness(rather than storytelling) to reveal abstract and subconscious tendenciesfar away from reality. Experimental cinema is inclined to express dreams,fears and desires, and to represent symbolization and psychologization.

2. Historical Background

(1) Experimental cinema originated from European “Avantgarde” films. In the First World War French and German filmmaking businesses were ruined, while only the U.S. movie industry boosted and won worldwide popularity, mostly featuring commercial films. When European fi lmmakers set about rising again, it was impossible for them to follow the same steps that the U.S. counterparts had taken. Artistic innovation became their sole choice to compete against U.S. commercial films and build their own cinema art.

(2) Culturally, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, modernist artistic thoughts emerging in Europe entered cinema. In modern philosophy existentialism emphasized the nature of human existence and the freedom of choice. In modern science relativity theory revolutionized traditional time-space ideas. And Freud’s unconscious psychology provided motive and background for experimental cinema, and shaped its creative practices.

3. Examples of Anti-narrative Experimental Cinema

(1) Entr’acte (1969)

This fi lm, directed by René Clair, is a plot-free avant-garde work.In a very surprising manner it rejects traditional logic narration, and replaces it with a connection between similar visual modellings of shots.The first half of the film consists of footages unrelated to each other,while the other half is a continuous interlude. Entr’acte begins with bombing, chess-playing, fi ring, funeral, and resurrection, and every event ends up in a farce-like manner until the end of the fi lm.1In such an antinarrative way, Clair links footages causally unrelated to each other, and criticizes bourgeois customs, fashions, practices, and etiquette, reducing a funeral, which should have been a solemn occasion, to a scene of crazy,funny chasing—a representation of cynicism in post-war youths.

Meshes of the Afternoon by Maya Deren is a self-videoing piece in a manner interwoven between fi ction and reality. And shot editing is abnormal. The film consists of five scenes of a woman’s dream in the afternoon, which, though sharing a beginning, differ in visual angles and plots, leading to different outcomes. Deren used unconventional creative methods which were not seen in the then mainstream fi lms—seemingly shaky shots, uneasy movements—successfully expressed the self at different levels and self-exploration as a woman.

4. Signi fi cance

Discouraged by the cruel post-war reality, many artists began to escape from the outside world and return to their inner worlds.They expressed their dissatisfaction and anxiety in a sinuous manner.Experimental films sought not so much formalistic anti-narrativity and purity as a new language expression. They expressed abstract and subconscious tendencies far away from reality. They emphasized the image expression of inner, spiritual worlds. For them cinema was a medium of expression and perception of the world and self-recognition,of rethinking the world and human nature, and of transcending life and aesthetic experience. All these proved it as a conscious genre of art,different from what it had been as a variety show at its outset.

Experimental fi lms employed life stream (an illogical combination of events) and stream of consciousness (irrational conscious activities) to replace or disrupt logic plot structure. With unconventional fragmented shot pastiche to destruct traditional techniques, it was indicative of human spiritual life and art life in modern society, enabling the audience to reevaluate society and human nature and return to their inner worlds.This turned out to have produced far-reaching impact upon the coming video art and new media art.

II. Video Art

1. Nature of Objective Recording

The 1960s saw the invention of video art. Though similarly antinarrative, it differed from experimental films, the latter revealing the inner world through shooting the actors’ performance. The initial impulse of videoing, however, was to record everything that met the eyes, to objectively show what reality was, not to carefully arrange or deal with each shot as in experimental cinema making. Then the images on the screen more depended on objective things available to life. But the difference lay in that artists, in a highly individualized way, employed video camera to record and represent them in a different manner. By doing so, they conveyed their points of view and personal experience as well; they also demonstrated that the world itself was not a mere objective reality, which contained the presence of consciousness, too.

2. Historical Background

(1) In 1925, the British engineer J. L. Baird invented television,using radio wave signals to instantly transmit moving visual images.In this way, images around the world, which could be watched only in the cinema before, were selectively available to ordinary families.By 1953, two-thirds of American families had owned TV sets. By 1960 the availability rate was up to 90 percent. Television achievedfull commercialization. The average daily hours which Americans spent on watching TV was up to 7 hours each. Thus a new consumer society came into being; advertising giants stimulated and maintained growth momentum in TV consumption. In 1965, Sony developed a small, portable camcorder and a matching image editing system. The increasingly popular TV sets and camcorders freed creation from limitations due to huge costs incurred in fi lm purchase. Video amateurs and common folk could use the latest technology to record and create images. Personal writing different from that in TV and filmmaking became possible. This played a great role in the media revolution of video art as a display tool, say, television.

(2) In addition, the 1960s were full of social upheavals. Millions of European and American youths began to hold values quite opposite to their parents’. And student political protests, feminist movements, and sexual revolution all contributed to the birth of video art.

(3) In 1965, the Korean-born artist NamJune Paik bought a portapak camera in New York. Later, he fi lmed the traf fi c jam caused by Pope John Paul’s visit to New York. Only after a few hours, the video clip was played in a Soho café. That day was regarded as video art’s birthday.

3. Video Art: Conceptuality; Combination with Performance and Installation

Admittedly, “recording” is the plainest practical video function.Early video art did take it as a realistic, objective approach, fully typical of this genre. However, if not going further, it would remain a passive, mechanical “recording” tool, not a truly independent form of art. Then artists discovered creative methods of video as an innovative medium—combining it with performance and installation to express their viewpoints.

(1) Conceptuality of video art

In the 1960s art ideas were stimulated by the media age (the control of TV over the daily life of the masses), and artists began to revolt against clichés prevalent in TV shows as a form of mainstream media. Therefore,they embraced video as a new language and method to voice their creative ideas. The theme of their work was often “anti-TV.” So video art showed obvious conceptuality at its early stage.2Unlike reporters who followed Pope for news photos, NamJune Paik aimed to produce a rough,non-commercial product, an expression of personal views. He discovered the recording function of video as a new form of media, and highlighted the new medium for individual presentation. The artist announced: “TV has occupied all aspects of our life. Now it’s time we fought back!”

In the mid-1960s, the film-maker Andy Warhol owned his first hand-held camcorder. With it he produced Factory Diary in 1965,recording various factory activities including workers’ daily life, such as eating, sleeping or talking to the camcorder. His work Sleep even videoed every minute, every second of a man’s six-hour sleep, which restored the original function of the camcorder—recording. Another example is his Empire (1964). At a single fi xed position he videoed the change of the Empire State Building in New York City for eight hours from evening to daybreak. It was by such real-time, consistent shooting that he recovered the original recording function of the camcorder.

(2) Video art: combining with performance

Influenced by performing art, early video art could be seen as a mere record of performance at a certain level, or later called “performing act.” Video artists aimed the camera at parts of their body and asked questions about what they meant as far as “humans” were concerned.

Vito Acconci produced several single-channel black-and-white video works in 1971, aiming the camera at his own body, and bringing the media to himself, directly speaking to the audience to explore the relationship between the viewer (or voyeur) and the viewed. In his work Theme Song (1973), he was lying on the fl oor before a sofa with blackand-white stripes, with his face occupying two thirds of the whole screen.He unceasingly invited the audience to join his scene by speaking: “I want you to come in.” From a male’s perspective he revealed a false connection that TV images brought the audience, and re fl ected an illusion that TV as a medium gave the viewer—af fi nity.

Joan Jonas, however, videoed her Left Side, Right Side by fi ddling with the camcorder and the mirror in such a weird manner that the audience was confused, unable to tell left from right when seeing the reverse images from the mirror. To further the audience’s confusion, she deliberately repeated: “This is my left side, this is my right side” until the viewer was thrown into complete bafflement, and the connection between them and TV images was disrupted. Like Acconci, Jonas also videoed herself for the purpose of performance, but in an unconventional approach to create a compelling feminist image as an individual in a way that involves her own body. She remarked: “I use video to expand my language, a poetic one. For me video is a spatial element that helps me devote myself to exploring language. I can crawl in and stay there exploring so.”

(3) Video art: combining with installation

Whether for simple recording or for individual performance,video art increasingly appeals to young artists who have grown up in an age saturated with media, with its seemingly infinite possibilities and relatively low affordability. Videoing is not only a method of participation in media, of overreaction to media, but also a means of representation of personal information. So far, artists have gained access to creative projects in a much wider range of physical size and expression. They,too, have had more personal and individualized creative motifs. Many have begun to create complex media installations. Now, apart from images, they can control the background which they design, and where images can be viewed in a complete environment.3

NamJune Paik’s video installation Electronic Superhighway (1995)includes dozens of television monitors piled in the exhibition hall, which look like image series in a universal database, involving secular politics and nuclear explosions in nature. The exterior of the installation is a miniature of the United States’ territory, consisting of 313 television sets marking the Continental U.S., 24 marking Alaska, one marking each Hawaii island, with national boundary made of steel structure, neon lights, and a 200-watt sound system. The superhighway is suggestive of crumbs of media culture, and the artist warns of war and cultural turmoil with these illuminating images.

Mary Lucier’s work Oblique House is a plasterboard room in which the interior altered by a car dealer has no window but a television monitor. She thinks that the building environment is about image and sound: inside the house in the open air is dark, and the TV monitor provides views that cannot be seen through the window; and that the work can go deep into the soul of the modern mind. The artist Adrian Piper in his What It’s Like, What It Is #3 (1991) inlaid the monitor in each side of the white box. The monitor illustrates the head of a black from different angles, and the video shows the black’s angry signs against racial discrimination: “I AM NOT LAZY!” “I AM NOT VULGAR!”“I AM NOT HORNY!” Here we see Piper of multiple identities:intellectual, artistic, racial, and individual.

4. Signi fi cance

Unlike experimental cinema, in which film organizing, shooting were carefully treated, video had an initial impulse to objectively record everything that met the eyes, the reality itself, which, then, would be left to and organized by the artist. In this context the screen images depended more on objective things available to our lives; the artist would record them with a camcorder and present them in a highly individual way, to counter-balance image abuse and commercialization, thus creating new viewing methods and personal experience. Video art as an avant-garde genre in the 1960s served as a role model in language transformation within the context of moving images. Its combination with performance and installation—a more tolerant creative mode—has had great impact upon later digital image creation. With the application of digital technology, video art, on the one hand, existed in a wider range of media culture; on the other hand, it kept certain distance from the culture. Such a predicament had become so worse that video artists had to define a unique art space to experience a greater freedom, where narration,perception and visual expectations would be reshuf fl ed.4

III. Digital Moving Images

1. Digital Technology: Recoding Video

Emerging digital moving image art has gone far beyond early video art in terms of implications as a means of presentation and recording.It has become an image art with comprehensive use of multi-image and installation environments centered on digital moving images as a core media carrier. Digitally, it recodes image structure and narrative discourse system. Either in narrative or non-narrative mode, it provides the viewer with non-linear aesthetic experience in a hyperlink media integration way: various collage techniques by non-linear editing;3-D collage of video installation; multimedia art link resulting from interactive art open to the viewer experience.5Applied digital technology has created new capabilities and offered images endless extensibility.What digital technology artists can do now is to introduce a new form of“creation,” rather than mechanically record objective reality as they did before. Previously, images could be edited in the movie or be recreated with a montage, and included into other images. However, once they are transferred to digital language, every element in them can be computermodified. In fact, images in the computer are numerous pieces of information, each of which can be operated.

In present-day video exhibitions, the concept of “video art” cannot cover all today’s moving image works. The first kind is non-recorded or non-videoed, e.g. virtual videos drawn by Maya, After effect or other computer software. Moreover, digital image material can be easily edited or treated with digital late software; non-linear editing has replaced previous linear editing. The Internet as a completely new communication platform makes real-time interaction with works possible. So, digital moving images, to a certain extent, have had new features in the context of today’s new technology that “video art” did not have.

2. Historical Background

With the development of science and technology, especially the use of computer digital image processing, digital editing and virtual imaging technology, network and interactive technology, great changes have taken place in material production; hence new breakthroughs in human thinking ways. It is against such a historical background that digital images emerged and gained momentum. Of course, there is another cause that visually, the viewer has had aesthetic fatigue over traditional video art. Owing to the blending of art and technology, imaging technology becomes easier for command and use. The limits to artists’ ideas due to material itself begin to wane. Artists have obtained more freedom than ever to use of media technology in creation, thus having greater creative passion. The image is no longer solitary; it is solidary. There is no longer a unique image as in art, but the manufacture of countless prints, a vast panoply of imagery synthetically reproducing the natural restlessness of the spectator’s eye.6

3. Works of Digital Moving Images

(1) Narrative of moving images rede fi ned

The French artist Pierre Huyghe’s Remake (1995) is a remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s film Rear Window (1953). In fact Huyghe would hire amateur actors to complete the original film scenes in each of his works. He said: “Only a few hours before the actual shoot could they see their lines. And that was exactly their problem. Everything—stammering, forgetting lines—was included in real-time recording.” As to digital video technology he used fi lm technology (with the help of a small sliding-rail vehicle and tracking lenses, etc.). But his narration was incomplete. Therefore, narrative effect in his films was lowered, and a new relationship was successfully created between the audience and the performance behavior.

A similar example of af fi nity in image treatment is 24 Hour Psycho(1993) by the British artist Douglas Gordon. It is a replay of Alfred Hitchcock’s horror film Psycho at a speed of two frames per second.Gordon made the original fi lm a silent one with digital post-technology.He did not change its narrative contents, but extended its period from 109 to 1440 minutes, exactly 24 hours! These slowed-down shots are like a collection of photos which we have met somewhere, reappearing before our eyes at an extremely slow pace. In the prolonged length of time, every detail is so unmistakably clear that shots are no longer that frightening as they were; every shot, every second seems to give rise to a new meaning.

(2) Non-narrativity of digital moving images

The American artist Paul Pfeiffer used postproduction digital editing technology to recreate and redefine ever-made videos. In John 3: 16(2000), he digitally altered fi ve thousand frames of the act of basketball shooting, and re-positioned them to help establish male blacks as idols,so as to highlight the event and present a performance clip of a frustrated male black sports amateur. Likewise, he used digital technology for recreation in his other works. For example, he removed leading roles in NBA and boxing from the view of the audience. Therefore, the artist successfully created a new narrative mode and a new concept of time by digital technology. Thanks to his effort, images are no longer solitary,fi xed, but reorganized, solidary, and recreated, synthetically reproducing the natural restlessness of the spectator’s eye; and the spectators will question the truth of experience while watching his work, and will face the task of creating their own experience and meaning of life.

For the Israeli multimedia artist Michal Rovner, however, any individual trait of life that she shoots is less identi fi able after complex digital editing is done. Her videos are full of hundreds of small, silent characters in simple clothes. Her work Time Left (2003) is a huge, wallto-wall video installation, which she made with digital editing tools. In it outlines of thousands of protesters march on, row after row, toward an unknown destination, together with buzzing electronic music. This is a narration without certain plot, an abstract scene, reminiscent of the condemned prisoners or survivors of the Tianqi Accident (also known as Wanggongchang Explosion, a mysterious tragedy that happened tothe capital of Beijing in the sixth year of the reign of Emperor Tianqi,i.e. 1626, during China’s Ming Dynasty). Or, perhaps they are pilgrims parading just toward an expected ritual of religious revelation. This,indeed, is full of so many implications, which set the audience thinking after the visual impact. For the artist, digital editing tools are for expressing her individual ideas.

(3) Interactive digital moving images

In “interactive digital moving images,” more attention is paid to the experience that the interaction of the work itself brings; images are increasingly transformed into experience, an art form that allows the audience to directly involve in work. The reason is that the artist has taken the audience as an integral part of the work into account while conceiving the work in mind. Such an interactive approach brings the audience experience, differing from that in any traditional work which influences the viewer through passive visual consumption and psychological hints. At this moment, what matters is no longer narrativity or non-narrativity, but experience available to the audience through interaction. Most of these interactive artworks are based on computer control and various sensors, by collecting the audience’s behavior,gestures, temperature and even language and other data information, and then feeding them back to the audience after processing. Hence a new dialogue mechanism between the work and the audience. Thus, every viewer is enabled to earn a personal experience in the artist-created,interactive environment. This also offers artists a means of leading the audience in a positive way to social concerns.

The Polish artist Tamas Waliczky played a perspective-shifting game in his interactive video installation The Way (1994). When the viewer approaches the projection screen placed at the far end of a long corridor, the screen images gradually diminish as he comes up closer,thus gaining an abnormal experience. Since a new context or expression itself can generate meaning, this also directly leads to a changed way of information perception.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s work Under Scan (2005) allows each participant to open a video artwork belonging to himself or herself through tracking sensors and multi-imaging technology. Within the scope of projection, the audience is detected by a computerized tracking system, which activates video-portraits projected within their shadow.The audience will “wake them up,” and have visual contact, physical or even verbal interaction with them. When the viewer walks away,the portrait eventually disappears. This system can accommodate 80 participants within 1200 square meters at the same time. For every seven minutes, the entire project stops and resets. The tracking system is shown in a brief “episode” lighting sequence. And the project is operated by a computer monitoring system equipped with a calibrating grid.

4. Signi fi cance

Marshall McLuhan (1911-1980) of Canada wrote: “In a sense,any new medium is a new language, a new coding method of dealing with experience. This method comes from new work habits, entirely from collective consciousness.”7With the advent of an era when art and technology join hands, video technology becomes easier for command and use. The limits to artists’ ideas due to material itself begin to wane.Artists, whose notions dominate mechanics, may use digital systems for operation and adapt original coding systems; “artistically process”multiple correlations: political, societal, philosophical, emotional, and experienced, in forms of television, cinema, video, performance and interaction, for the sake of creation; and invest spiritual elements into work, and interpret results. So, their mental images are illustrated on the screen, which provides much more possibilities for image transformation and recreation.

Today, digital moving images have penetrated into all aspects of human life, which carry new trends for video art, and bring unprecedented experience, too. They play an important role in an era of big data and informatization, where value, meaning, experience, and new reality will all be established through participation.

IV. Conclusion

Technological advances—from experimental cinema, video art using hand-held camcorders in the 1960s and 1970s to today’s digital moving images—have empowered us to more extensive freedom for artistic creation. Specifically, from films in experimental cinema very carefully shooting in an anti-narrative manner to highlight expression of the inner world, to the camcorder objectively recording reality, then to digital technology recoding videos in a narrative or non-narrative manner, developing media technologies provide artists with possibilities of extending their space. In the process of “decoding” and “transforming,”artists create their individualized and contagious work by unique uses of tools, technology, procedure and display devices, depending on their personality and accomplishments. Although the above can be partly attributed to the progress of technology and art equipment, it is artists’skills and ideas that ultimately push on art to grow. Therefore, art should be a form that is more controlled by human consciousness than by overwhelming technology. Presumably, this comprehensive method of conscious control is a new perspective seeking to go beyond traditional narrative models, and to observe and understand this world in a different way.8 Ours is an age when commercialism runs rampant and gnaws life experience. In this void reality the artist resorts to a variety of new media to concretize our spirit, perception and experience, though not as a speci fi c object. He adds to them his individual spiritual and emotional experience, then concretizes such an experience carrier, making it responsible for carrying the temperature of human consciousness and inherent spirit and rebuilding a life-experiencing world.

This paper has been an attempt to reexamine the whole process from the origin of moving images, from early experimental cinema,video art, to today’s digital moving images; to explore how artworks vary with creative methods in each stage, and how the artist employs different methods to present individual ideas. In addition, it discussed how the artist fi nds creative methods suited to himself as old media give their way to new ones. As mentioned earlier, this paper is not intended to enumerate the stages from experimental movies, video art, to digital moving image,or to analyze this transition. Instead, considering one hundred years of evolving media and creative methods, it remains concerned about how moving images as a genre grow, evolve and keep their momentum in the context of new technology and media, and how they bring greater freedom and diversi fi ed possibilities to creation. Here, value, meaning,experience, and new realities will be all established through participation.

Notes:

1 See “An Outline of French Surrealist Cinema,” Journal of School of Chinese Language and Culture Nanjing Normal University, Issue 3, 2005.

2 Sun Weiwei: “Moving Image Art: Artistic Expression & Characteristics Analysis, Based on Experimental Cinema, Video Art and New Media Images,”Journal of Wuhan University of Science and Technology (Social Science Edition),Issue 2, 2013.

3 Michael Rush: New Media Art, Shanghai People’s Fine Arts PublishingHouse, 2015.

4 ibid.

5 Zhihu.com: “How Should We Understand Video Art? ” (http://www.zhihu.com/question/36891170)

6 Paul Virilio: The Vision Machine, trans. Zhang Xinmu and Wei Shu,Nanjing University Press, 2014.

7 Artda.cn: Video Art in Late 20th Century, source: art publication circle, author: Michael Rush, trans. Xiao Sha (http://www.artda.cn/view.php?tid=5728&cid=20).

8 Gao Minglu, Chen Xiaowen: Contemporary Digital Art, Guangxi Normal University Press, 2015.

[1] A.L. Rees. A History of Experimental Film and Video [M]. Trans. Yue Yang. Changchun: Jilin Publishing Group, 2011.

[2] Michael Rush. New Media in Art [M]. Trans. Yu Qing. Shanghai:Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2015.

[3] Michael Archer. Art Since 1960 [M]. Trans. Liu Si. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2015.

[4] Gao Minglu, Chen Xiaowen. Contemporary Digital Art [C]. Guilin:Guangxi Normal University Press, 2015.

[5] Chen Jianjun. Cutting-Edge Video Art [M]. Nanjing: Jiangsu Fine Arts Publishing House, 2007.

[6] Zhang Shijun. Foreign Films History [M]. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press, 2014.

[7] Zhou Xing. Essentials of Cinema [M]. Beijing: Higher Education Press,2004.

[8] Paul Virilio. The Vision Machine [M]. Trans. Zhang Xinmu and Wei Shu.Nanjing: Nanjing University Press, 2014.

[9] Nicholas Bourriaud. Postproduction [M]. Trans. Xiong Wenxi. Beijing:Gold Wall Press, 2014.

[10] Dong Bingfeng, et al. Looking through Film: Traces of Cinema and Self-Constructs in Contemporary Art [M]. Beijing: New Star Press, 2010.

[11] E.H. Gombrich. The Story of Art [M]. Trans. Fan Jingzhong. Nanning:Guangxi Fine Arts Publishing House, 2014.

[12] Sun Weiwei. Between Rosy Dream and Actual Pain: Video under the Lens of Eastern and Western Female Artists [J]. Theory Monthly, 2013 (1): 73-77.

[13] Sun Weiwei. Moving Image Art: Artistic Expression & Characteristics Analysis, Based on Experimental Cinema, Video Art and New Media Image [J].Journal of Wuhan University of Science and Technology: Social Science Edition,2013 (2): 227-232.

[14] How Should We Understand Video Art? [EB / OL]. [2016-2-21]. http://www.zhihu.com/question/36891170

Developing Creative Methods of Moving Images:from Experimental Cinema, Video Art to Digital Moving Images

Text by Yue Minghui and Hao Rui, translated by Yue Zhongsheng

In the 20thcentury, avant-garde artists introduced technology-based art (from photography, cinema, video to virtual reality,and many others lying between them) to the territory once dominated by engineers and technicians. They brought every new material and medium to art and rendered much more freedom to its creation. This paper attempts to examine the historical line of moving images and their creative methods in different stages, and explore how they as a genre of art represent themselves and grow in the context of new technologies to accommodate artistic creation with richer and more diversified possibilities.

creative method; moving images; experimental cinema; video art; digital moving images

This paper is supported by Youth Fund of Tianjin Normal University(52WU1603)

Yue Minghui: teacher at School of Art and Design, Tianjin Normal University

Hao Rui: current postgraduate of Mixed Media Painting Department, School of Experimental Art, Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts

Yue Zhongsheng: associate professor at Civil Aviation University of China