南亚热带红椎和格木人工幼龄林土壤微生物群落结构特征

洪丕征,刘世荣,*,王 晖,于浩龙

1 中国林业科学研究院森林生态环境与保护研究所,国家林业局森林生态环境重点实验室,北京 100091 2 中国林业科学研究院热带林业实验中心,凭祥 532600

南亚热带红椎和格木人工幼龄林土壤微生物群落结构特征

洪丕征1,刘世荣1,*,王晖1,于浩龙2

1 中国林业科学研究院森林生态环境与保护研究所,国家林业局森林生态环境重点实验室,北京 1000912 中国林业科学研究院热带林业实验中心,凭祥 532600

南亚热带;固氮树种;非固氮树种;土壤微生物群落

土壤微生物群落是森林生态系统养分循环、有机质分解、养分有效性、土壤结构形成等关键过程的积极参与者[1-4]。同时,作为土壤中最具活力的部分,土壤微生物与土壤肥力和土壤健康状况紧密相连,也作为评价不同经营措施对土壤特征影响的生态学指标。土壤微生物群落的数量和比例是表征土壤生态系统群落结构和稳定性的重要参数之一,它能较早地预测土壤养分及环境质量的变化,被认为是最有潜力的敏感性生物指标之一[5-6]。了解森林土壤微生物生物量和微生物群落结构的变化有助于对森林生态系统功能的变化做出解释。评估土壤管理活动对土壤微生物群落结构、多样性及活性的影响对推动人为管理与自然生态系统的功能性、稳定性及恢复潜力至关重要[7]。

目前,国外有关固氮树种(N-fixing tree species)与非固氮树种(non-N-fixing tree species)对土壤微生物群落影响的研究相对较少,但仍取得了一些成果[8],尽管这些结论未达成共识。研究表明,相比于非固氮树种,固氮树种对林地土壤微生物群落结构产生不同程度的影响[8-10]。例如,Boyle等[9]在北美西北部森林中研究发现非固氮树种花旗松(Pseud-otsugamenziesii)林和固氮树种红桤木(Alnusrubra)林中土壤微生物群落组成无显著差异。与之类似,Bini等[10]研究发现固氮树种马占相思(Acaciamangium)幼龄林与非固氮树种巨桉(Eucalyptusgrandis)幼龄林中土壤微生物生物量碳氮含量无显著差异,但马占相思幼龄林土壤脱氢酶(Dehydrogenase enzyme)活性显著高于巨桉幼龄林,这表明固氮树种与非固氮树种林下土壤微生物群落结构和微生物活性存在差异。Hoogmoed等[8]研究发现,尽管固氮树种(银荆,Acaciadealbata;灰木相思,Acaciaimplexa)与非固氮树种(赤桉,Eucalyptuscamaldulensis;多花桉,Eucalyptuspolyanthemos)林下土壤微生物群落结构无显著差异,但在物种水平上固氮树种银荆林下土壤微生物群落结构与非固氮树种赤桉和多花桉存在显著差异,并且银荆林土壤微生物总PLFAs量最高。以上研究表明,固氮树种与非固氮树种对土壤微生物群落的影响仍存在着较大的不确定性,因此,有必要开展相关研究以进一步明确固氮树种与非固氮树种对土壤微生物群落的影响。

在我国亚热带地区,人工造林、再造林已成为森林培育和经营的重要方式[11]。然而,随着大规模、持续单一人工针叶林如马尾松(Pinusmassoniana)和杉木(Cunninghamialanceolata)等,或桉树(Eucalyptus)等外来树种短周期工业用材林的发展,造成了诸如生物多样性丧失、土壤退化、生态系统稳定性降低等问题[12]。为促进人工林的多目标经营,提高人工林的生态功能和经济价值,许多乡土珍贵阔叶树种(包括固氮树种)逐渐被用于亚热带人工林营建的生产实践中。近年来,有关不同林分对土壤微生物生物量和群落结构的影响方面的研究国内外已有报道[11-14],然而,对固氮树种与非固氮树种人工纯林营建初期土壤微生物响应的研究相对缺乏。非固氮树种红椎(Castanopsishystrix)和固氮树种格木(Erythrophloeumfordii)是热带、亚热带地区常见的珍贵乡土树种,在林业生态工程建设中占重要地位,在我国亚热带地区大面积种植。为此,本文以我国南亚热带具有相同经营历史与立地条件的红椎和格木人工幼龄林为研究对象,采用磷脂脂肪酸法(Phospholipids fatty acid,PLFA)研究比较不同营林模式下人工林土壤微生物生物量和微生物群落结构的季节变化,以及土壤微生物与环境因子的相关关系,以期为深入认识该地区不同树种人工林的生态功能,特别是土壤微生物的生态功能提供科学依据。

1 研究区域与方法

1.1研究区概况

试验地位于广西壮族自治区凭祥市境内的中国林科院热带林业实验中心哨平实验场(22°3′3.8″N,106°54′17.5″E)。该地区属于南亚热带季风气候,属湿润半湿润气候,干湿季节分明。境内光照充足,降水充沛,年平均降水量为1400 mm,主要发生在4—9月。年蒸发量1261—1388 mm,相对湿度80%—84%。年平均气温20.5—21.7 ℃,平均月最低温度12.1 ℃,平均月最高温度26.3 ℃;≥10 ℃活动积温6000—7600 ℃,年均日照时数1419 h。主要地貌类型以低山丘陵为主,地带性土壤以红壤为主,主要由花岗岩风化形成。

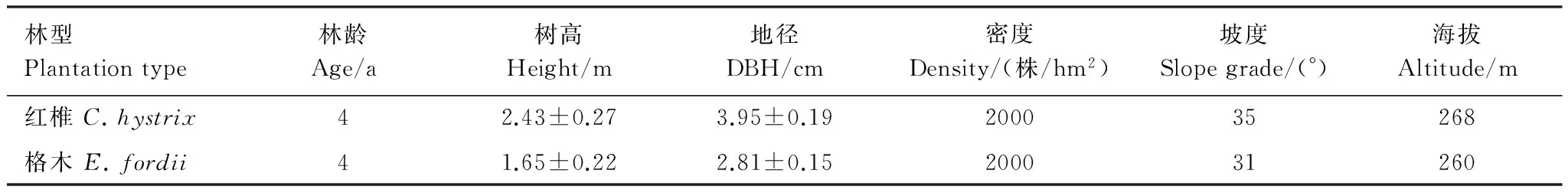

选择该区域2010年营建的红椎、格木人工幼龄试验林为研究对象,造林地为杉木人工林采伐迹地,立地条件基本一致。在同一坡面建立6个实验小区,每个小区的面积为1 hm2,采用随机区组设计,每个区组3个重复,分别为造林树种红椎和格木。各个小区均采用同一密度造林,株行距均为2 m×2.5 m,造林时未进行炼山、施肥等管理措施,每年进行2次除草。草本优势种主要为五节芒(Miscanthusfloridulus)。研究地林分基本情况见表1。

表1 研究地林分基本情况

1.2试验设计与样品采集

于2012年4月分别在红椎、格木幼龄林各个小区的相同坡位随机建立1个20 m×20 m的样方,根据当地气候特点分别于2013年1月(旱季)和8月(雨季)进行土壤样品取样。在每个样方随机选取8个点,用不锈钢土钻(直径8 cm)采集0—10 cm表层土壤,然后混合为一个样品尽快带回实验室。实验室内先测定新鲜土样品的土壤含水量,然后2 mm过筛,将样品分为2份,其中一份置入-20 ℃冰箱中冻存,1周内完成土壤微生物群落组成的测定,另一份自然风干后过0.25 mm细筛,以待土壤理化性质分析。

1.3分析方法

1.3.1土壤微生物碳氮测定方法

土壤微生物生物量碳(microbial biomass carbon, MBC)和微生物生物量氮(microbial biomass nitrogen, MBN)采用氯仿熏蒸浸提法测定[15]。其中熏蒸处理为25 ℃真空条件下培养48 h,采用0.5 mol/L K2SO4浸提液提取。采用全有机碳自动分析仪(TOC-VCPH,日本岛津)测定抽提液中的有机碳和全氮含量。MBC和MBN (mg/kg)的计算方法如下[16-17]:

MBC = 2.22 EC

(1)

MBN = 2.22 EN

(2)

式中,EC、EN分别为熏蒸和未熏蒸土样浸提液中的有机碳、全氮的差值;2.22为校正系数。

1.3.2微生物群落组成的测定

土壤基本理化性质测定方法参见《土壤农业化学分析方法》[18]。土壤微生物生物量和微生物群落结构采用磷脂脂肪酸法(PLFA)进行测定[19]。该方法以酯化C19:0为内标,用安捷伦6890气相色谱仪(Hewlett-Packard 6890,美国安捷伦)进行测定。单个脂肪酸种类用nmol/g干土表示,每种脂肪酸的浓度基于碳内标19:0的浓度来计算。单个PLFA的相对丰度用摩尔百分比(mol %)表示。本研究中,PLFAs i14:0、i15:0、i16:0、i17:0、a15:0、a17:0用来指示革兰氏阳性菌;PLFAs 16:1ω7c、18:1ω7c、cy17:0、15:0 3OH和16:1 2OH用来指示革兰氏阴性菌;放线菌用PLFAs 10Me 16:0, 10Me 17:0和10Me 18:0来指示;PLFAs 16:1ω5c则用来指示丛枝菌根;PLFAs 18:2ω6,9c和18:1ω9c用来指示真菌[5, 20-21]。真菌细菌比的计算方法为:(PLFAs 18:2ω6,9c、18:1ω9c / PLFAs i14:0, i15:0, i16:0, i17:0, a15:0, a17:0, 16:1ω7c, 18:1ω7c, cy17:0, 15:0 3OH、16:1 2OH)[5, 20-21]。

1.3.3土壤PLFA多样性指数

首先,校级、院级督导小组听课的主要效果更像一种检查和督促,其疏导作用、相互交流作用、相互提升作用越来越弱。再加上教师的教学任务和督导的听课任务都比较重,进一步接触的时间和机会很少。校级、院级督导小组听课的效用没有在很大程度上体现出来,在督导听课过程中遇到一些违规现象,常常无法及时处理[8]。

PLFA丰富度指数(R)为每个土壤样品中出现的脂肪酸种类[22-23],PLFA多样性指数用Shannon多样性指数(H)来表征[23],其计算方法如下[23]:

(3)

式中,pi为每个脂肪酸的相对丰度,R为被检测出的脂肪酸种类,PLFA均匀度指数采用Shannon′s均匀度指数(E)[22],其计算方法如下[22]:

(4)

1.4数据分析与处理

运用SPSS 19.0对土壤微生物及环境变量的差异进行单因素方差分析(one-way ANOVAs)(P<0.05)。利用双因素方差分析(twoway ANOVAs)检验林分类型、季节及其交互作用对微生物变量的影响。不同林分和季节下土壤微生物群落结构的差异、土壤微生物群落结构的变化与土壤理化性质的关系运用CANOCO 4.5软件(Microcomputer Power, Inc., Ithaca, NY)分别进行主成分分析(principal component analysis, PCA)与冗余分析(redundancy analysis, RDA)。绘图采用Origin Pro 9.0 软件。

2 结果与分析

2.1土壤性质

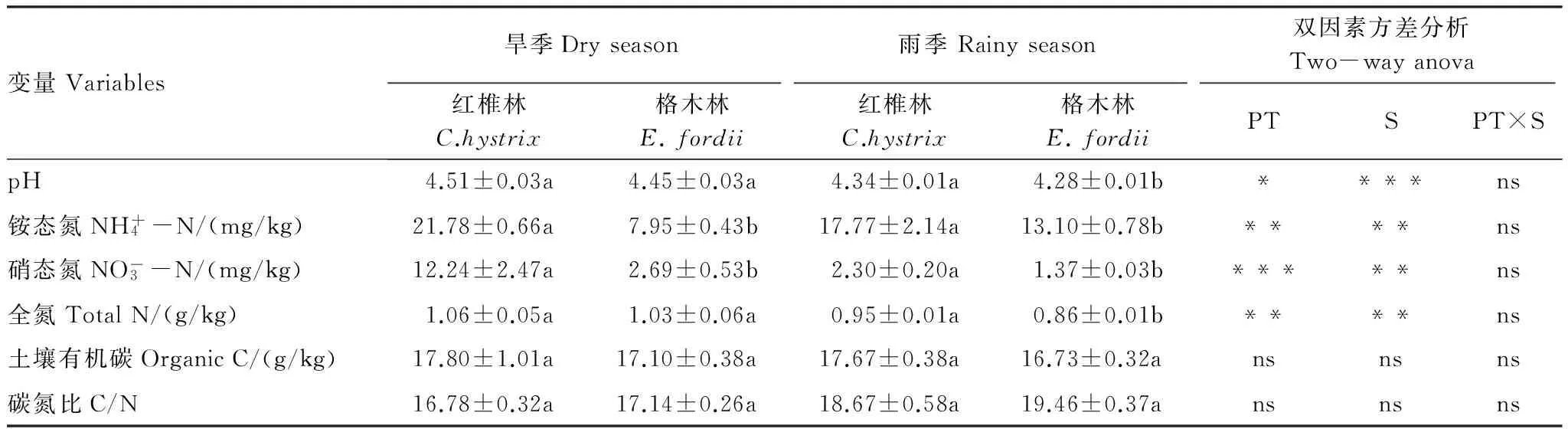

2种林分干湿季节的土壤性质见表2,林分和季节均显著影响了土壤pH、全氮、铵态氮和硝态氮含量,但对土壤有机碳含量及土壤碳氮比的影响不显著。由表2可以看出,2种林分土壤pH在旱季无显著差异,但在雨季格木幼龄林土壤pH显著低于红椎幼龄林(P<0.05)。不同季节红椎幼龄林土壤铵态氮和硝态氮含量均显著高于格木幼龄林(P<0.05)。2种林分旱季的土壤pH、全氮、铵态氮和硝态氮含量均大于雨季(P<0.05)。

表2 不同季节2种林分土壤性质的对比

PT:林分 Plantation type;S:季节 Season;不同小写字母表示林分间的差异达到显著水平(P<0.05); *, **, ***分别代表显著性水平P<0.05,P<0.01和P<0.001

2.2土壤微生物生物量

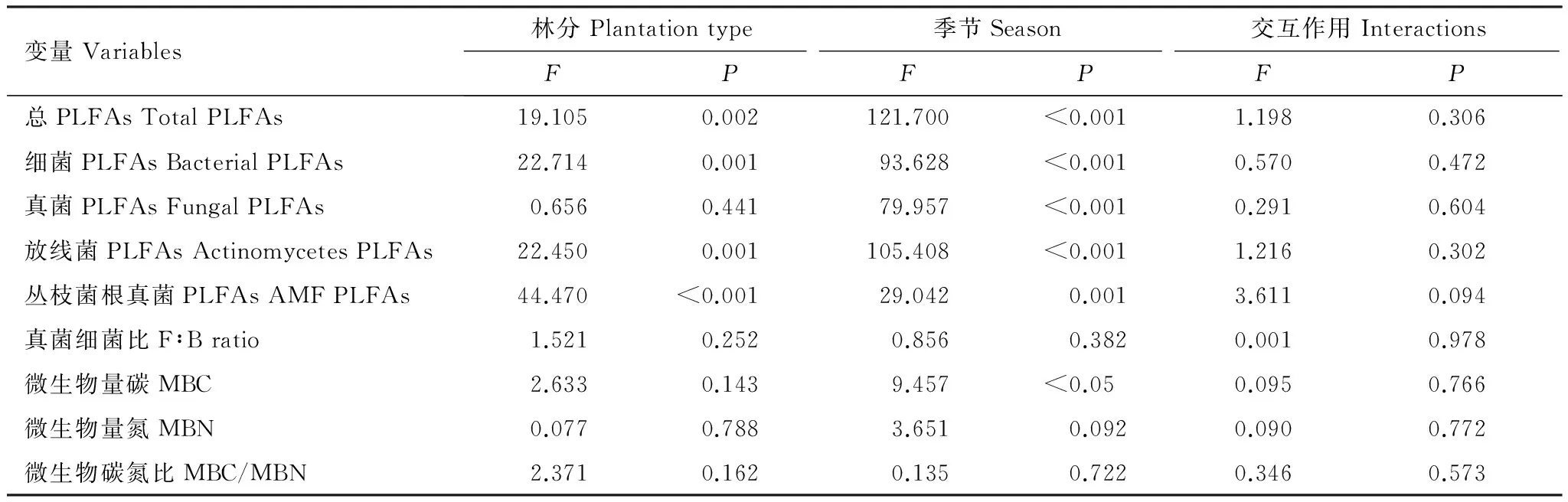

表3 林分、季节及其交互作用对土壤微生物生物量的影响

PLFAs: 磷脂脂肪酸 Phospholipids fatty acids;AMF:丛枝菌根真菌Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi;F∶B: 真菌细菌比 Ratio of fungal to bacterial PLFAs; MBC: 微生物生物量碳Microbial biomass carbon;MBN: 微生物生物量氮 Microbial biomass nitrogen; MBC/MBN: 微生物生物量碳氮比 Ratio of microbial biomass carbon to nitrogen

图1 不同季节2种林分土壤微生物生物量碳、氮含量的对比Fig.1 Comparisons of soil MBC and MBN contents in two plantations in different seasons不同小写字母表示林分间的差异达到显著水平(P<0.05),Significant differences (P<0.05)among plantations are indicated by different letters

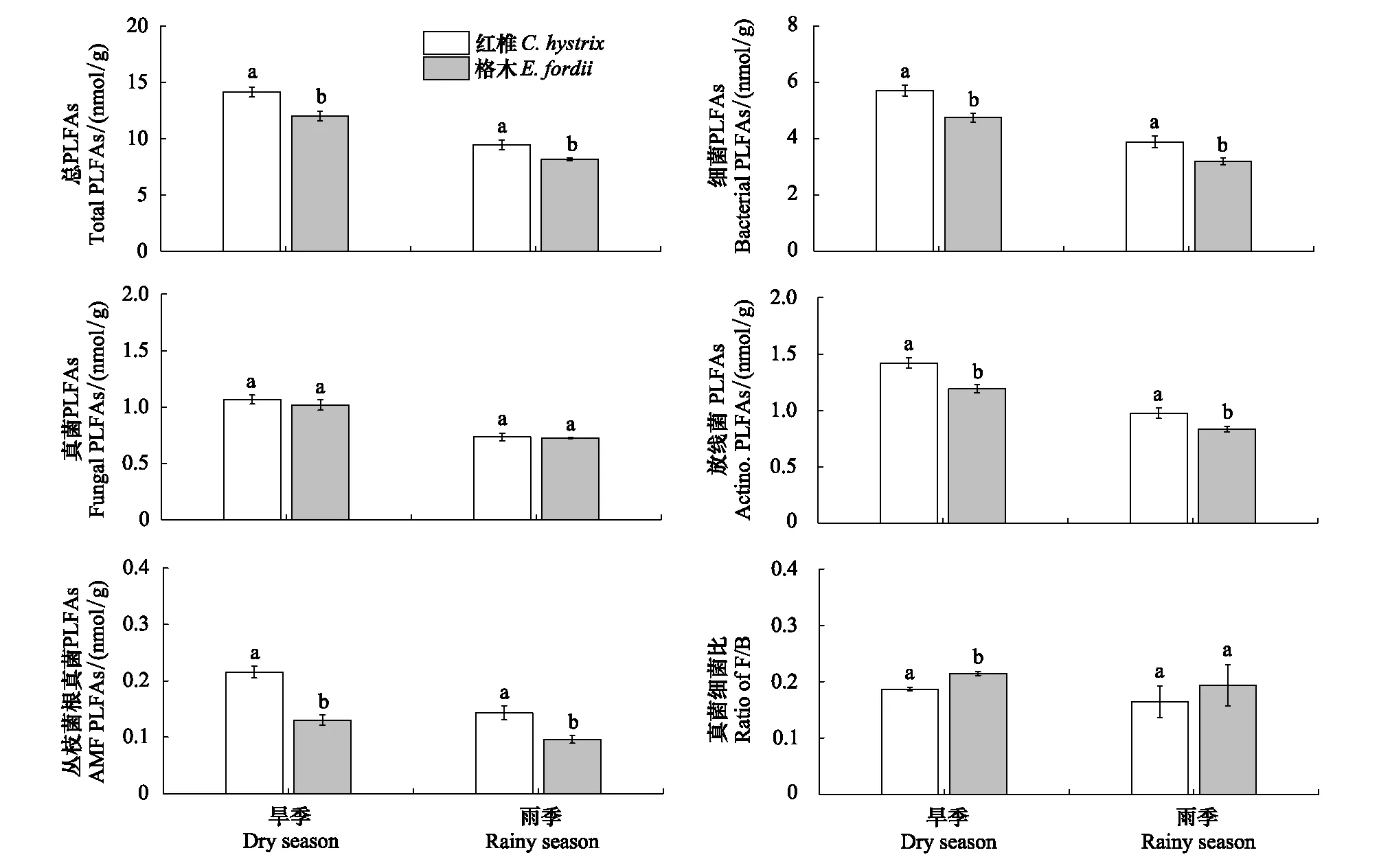

总体来说,林分与季节对土壤微生物总PLFAs量、细菌PLFAs量、放线菌PLFAs量及丛枝菌根真菌PLFAs量均产生了显著影响,而季节仅对土壤真菌PLFAs量的影响显著(表3)。在雨季和干季,红椎幼龄林土壤微生物总PLFAs量、细菌PLFAs量、放线菌PLFAs量及丛枝菌根真菌PLFAs量均显著高于格木幼龄林,而土壤真菌PLFAs量在2种林分中无显著差异(图2)。

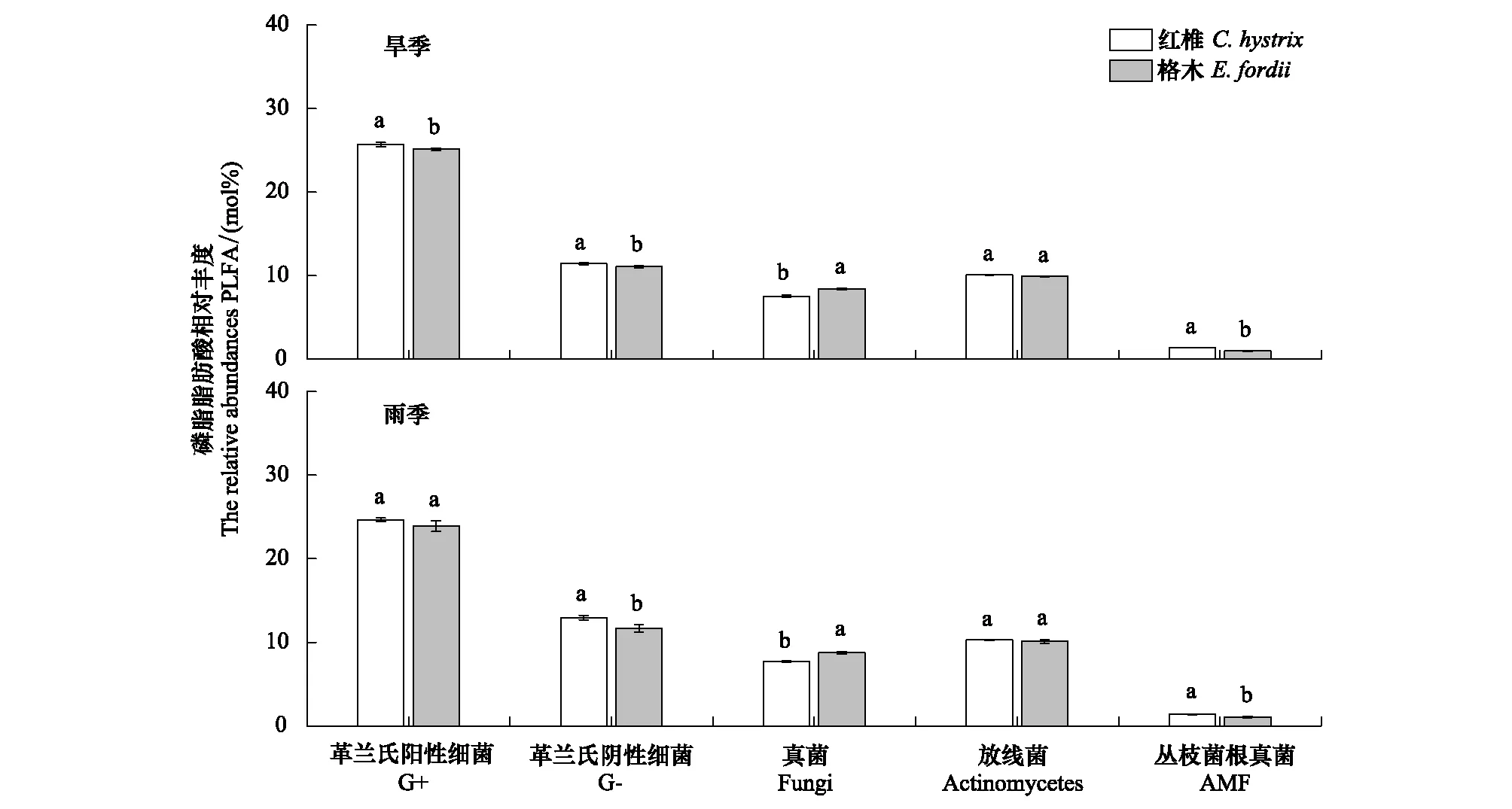

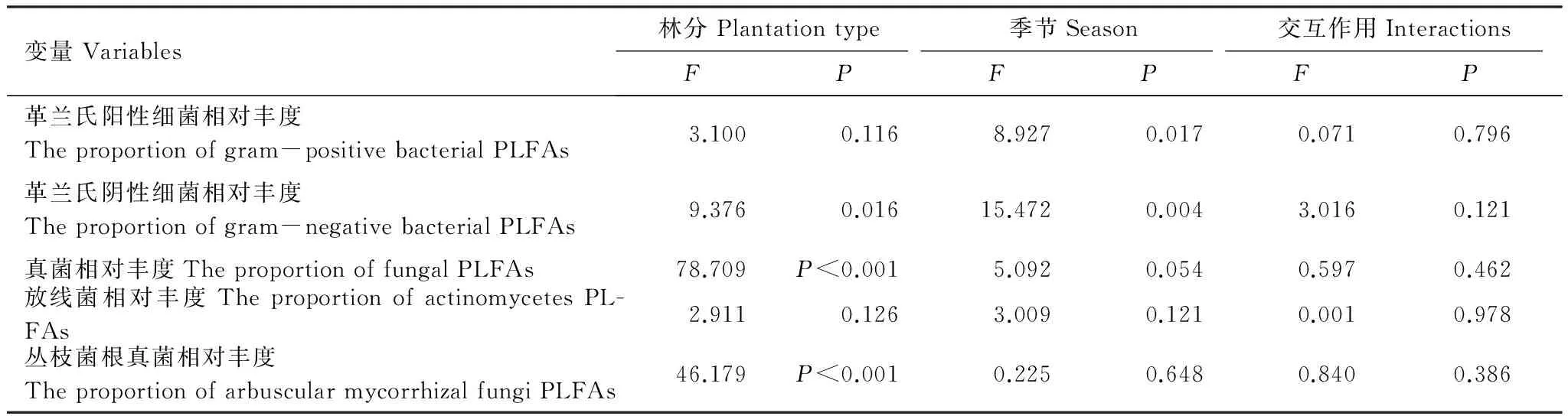

2.3土壤微生物群落结构

方差分析结果表明,土壤微生物真菌细菌比未受到林分、季节及其交互作用的显著影响(表3)。在旱季,格木幼龄林中土壤微生物真菌细菌比显著高于红椎幼龄林(P<0.05),在雨季则无显著差异(P>0.05)(图2F)。林分与季节对革兰氏阳性细菌PLFAs和革兰氏阴性细菌PLFAs的相对丰度均产生了显著影响,然而林分仅对真菌PLFAs和丛枝菌根真菌PLFAs的相对丰度产生了影响显著(表4)。在旱季,红椎幼龄林土壤革兰氏阳性细菌PLFAs的相对丰度显著高于格木幼龄林(P<0.05),在雨季其在2种林分中则无显著差异(P>0.05)。无论雨季还是干季,红椎幼龄林土壤革兰氏阴性细菌PLFAs和丛枝菌根真菌PLFAs的相对丰度均高于格木幼龄林,而真菌PLFAs相对丰度均显著低于格木幼龄林(图3)。

对不同林分和季节下土壤中所提取的27种磷脂脂肪酸进行主成分分析,结果表明,第1、2主成分对土壤微生物群落结构差异的贡献值分别为68.4%、17.4%(图4)。红椎幼龄林与格木幼龄林沿第二主成分轴可明显分开,说明2种林分的土壤微生物群落结构存在显著差异。2种林分在旱季、雨季的微生物群落结构沿第一主成分轴可明显区分开,说明2种林分的土壤微生物结构存在着显著的季节变化(图4A)。

图2 不同季节2种林分土壤微生物PLFAs量的对比Fig.2 Comparisons of soil microbial PLFAs content in two plantations in different seasonsPLFAs: 磷脂脂肪酸 Phospholipids fatty acids;Actino.:放线菌Actinomycetes;AMF:丛枝菌根真菌Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi;F/B: 真菌细菌比 Ratio of fungal to bacterial PLFAs

图3 不同季节2种林分土壤微生物群落磷脂脂肪酸的相对丰度Fig.3 Relative abundances of the microbial community PLFAs in two plantations in different seasonsG+:革兰氏阳性细菌Gram-positive bacteria;G-:革兰氏阴性细菌Gram-negative bacteria;AMF:丛枝菌根真菌Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

图4 土壤微生物群落结构主成分分析(A)和磷脂脂肪酸初始载荷因子主成分分析(B)Fig.4 Principal component analysis of soil microbial community structure (A) and eigenvector of phospholipid fatty acids contributing to soil microbial communities ordination pattern (B)CH: 红椎幼龄林 C. hystrix plantation;EF: 格木幼龄林 E. fordii plantation;D: 旱季 Dry season; R: 雨季 Rainy season

PLFA初始载荷因子主成分分析结果表明,单一磷脂脂肪酸中,对第一主成分起主要作用的是真菌PFLA生物标记(18:2ω6,9c 和18:1ω9c),革兰氏阳性细菌PLFA生物标记(i16:0和 i17:0)及革兰氏阴性细菌标记物16:1 2OH。而革兰氏阴性细菌PFLA标记物(16:1ω7c, 18:1ω7c, cy17:0)及放线菌PLFA生物标记(10Me 16:0、10Me 17:0、10Me 18:0)对第二主成分轴的贡献较大(图4B)。

表4 林分、季节及其交互作用对土壤微生物群落结构的影响

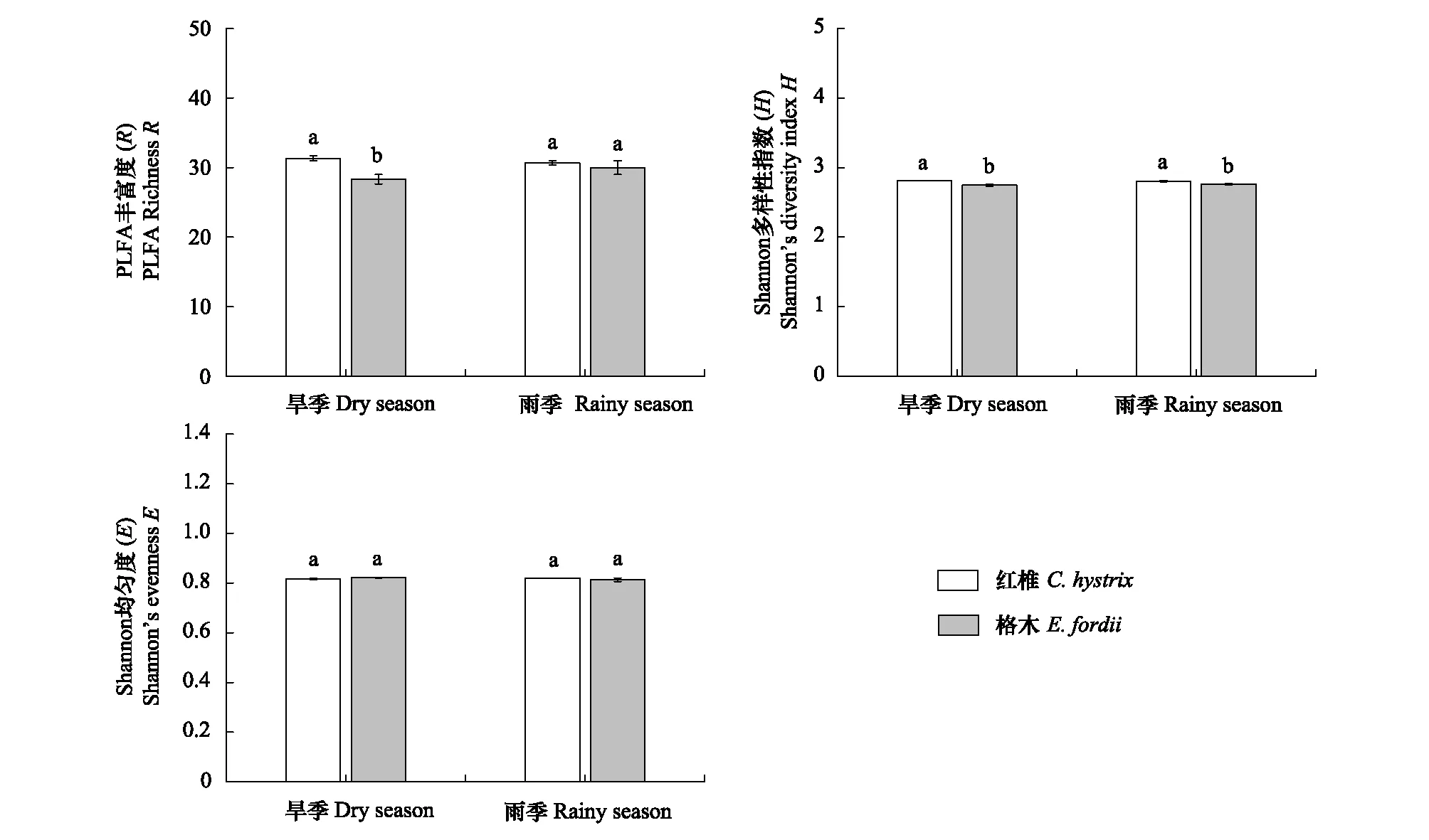

2.4土壤微生物群落PLFA多样性

方差分析结果表明,仅林分因素显著影响了PLFA丰富度(F=8.067,P=0.022)与PLFA多样性(F=28.483,P=0.001),而林分、季节及其交互作用对土壤PLFA均匀度均未产生显著影响。在旱季,红椎幼龄林土壤PLFA丰富度显著高于格木幼龄林(图5)。此外,在旱季和雨季红椎幼龄林土壤PLFA多样性均大于格木幼龄林(图5)。

图5 PLFA多样性指数Fig.5 PLFA diversity indices

2.5土壤微生物群落变化与土壤理化性质的关系

相关分析表明,土壤微生物总PLFAs与土壤pH、铵态氮、硝态氮、全氮、MBC及MBN呈显著正相关,然而与土壤含水量和土壤温度呈极显著负相关。革兰氏阳性细菌的相对丰度与pH、铵态氮、硝态氮、全氮及MBC呈显著正相关,但与土壤含水量、土壤温度呈显著负相关。革兰氏阴性细菌的相对丰度与土壤含水量、土壤温度呈显著负相关。此外,真菌相对丰度与铵态氮、硝态氮、全氮及MBC呈显著负相关,丛枝菌根真菌的相对丰度与铵态氮及硝态氮呈显著正相关(表5)。

表5 土壤微生物总PLFAs和微生物群落结构与环境因子的相关分析

对2种林分土壤微生物群落结构与土壤理化性质进行冗余分析,结果表明,11个变量包括土壤温度、土壤含水量、pH、有机碳、铵态氮、硝态氮、全氮、碳氮比、微生物生物量碳、微生物生物量氮和微生物生物量碳氮比共解释了土壤微生物群落结构变化的85.4%。其中,第1轴共解释了68.4%的变异,第2轴解释了17.0%。Monte Carlo检验表明,土壤微生物群落结构与硝态氮(F=10.74,P=0.002)、土壤含水量(F=8.11,P=0.002)、pH(F=3.11,P=0.038)和微生物生物量氮(F=2.38,P=0.048)显著相关。硝态氮与Axis 1轴呈显著正相关,土壤含水量与Axis 2轴呈显著正相关,而微生物生物量氮、pH与Axis 2轴呈显著负相关(图6)。

图6 土壤微生物单个PLFA与土壤理化性质的冗余分析Fig.6 Redundancy analysis on the individual PLFAs and soil propertiesSWC:土壤含水量 Soil water content; ST:土壤温度 Soil temperature;SOC:有机碳 Soil organic carbon; Ammonia-N:铵态氮;Nitrate-N:硝态氮; TN:全氮 Total nitrogen; C/N:碳氮比 Ratio of soil carbon to nitrogen; MBC:土壤微生物生物量碳 Microbial biomass carbon;MBN:土壤微生物生物量氮 Microbial biomass nitrogen; MBC/MBN:土壤微生物生物量碳氮比 Ratio of MBC/MBN

通过单个PFLA与环境因子相关关系排序可以发现,土壤含水量与放线菌PLFA标记(10Me16:0、10Me17:0)呈显著正相关,即这些PLFAs的相对丰度随着土壤含水量的升高而升高。硝态氮含量与丛枝菌根真菌PLFA标记(16:1ω5c)、革兰氏阴性菌PLFA标记(cy17:0、18:1ω7c、15:0 3OH)、放线菌PLFA标记(10Me18:0)及革兰氏阳性细菌PLFA标记(i15:0、a15:0)呈显著正相关(图6)。土壤pH和MBN与革兰氏阳性细菌PLFA标记i14:0呈显著正相关(图6)。

3 讨论

一般来说,土壤微生物群落的季节变化与土壤温湿度的季节变异密切相关[24]。与旱季相比,雨季的土壤温湿度条件往往更利于土壤微生物的生长。然而,本研究却发现旱季土壤微生物的PLFAs总量和主要菌群PLFAs量均要高于雨季(图2),与白震等[25]和Rogers[26]等研究发现雨季微生物生物量较高的结果并不相同。他们认为,雨季的温湿度更有利于植物凋落物的分解,加上植物因旺盛生长而向土壤中分泌的大量有机碳等易降解底物,土壤中可利用底物丰富,有利于微生物的生长。而Lipson等[27]、牛佳等[28]和王卫霞等[14]在研究不同季节条件下土壤微生物群落结构特征时,得到与本研究相似的结论。在旱季,植物的凋落物量较大,加上土壤通气性较好,土壤中溶解性氧含量增多,有利于需氧微生物的生长,微生物生物量较高[28-29]。因此,影响土壤微生物的因素较多,其生物量的高低仍取决于起关键作用的影响因素。本研究中,雨季土壤MBC最低,干季最高,其原因可能是植物在雨季对土壤养分的大量需求限制了土壤微生物对养分的可利用性,暗示了植物生长对养分的吸收与土壤微生物对体内养分的保持具有同步性[14,30]。

综上所述,在我国南亚热带地区,固氮树种格木与非固氮树种红椎用于人工林改建后,固氮树种有进一步加剧土壤酸化的趋势,在造林初期土壤微生物生物量和微生物群落结构存在显著差异,说明这2种林分对土壤微生物群落产生了不同的影响。同时,土壤pH和氮素状况可能是调控这2种林分土壤微生物生物量和群落结构的主要生态因子。

[1]Kirk J L, Beaudette L A, Hart M, Moutoglis P, Klironomos J N, Lee H, Trevors J T. Methods of studying soil microbial diversity. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 2004, 58(2): 169-188.

[3]Schloter M, Dilly O, Munch J C. Indicators for evaluating soil quality. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2003, 98(1/3): 255-262.

[4]Allison S D, Martiny J B H. Resistance, resilience, and redundancy in microbial communities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences the United States of America, 2008, 105(Supplement 1): 11512-11519.

[5]Cao Y S, Fu S L, Zou X M, Cao H L, Shao Y H, Zhou L X. Soil microbial community composition under Eucalyptus plantations of different age in subtropical China. European Journal of Soil Biology, 2010, 46 (2): 128-135.

[6]Xu Z F, Hu R, Xiong P, Wan C, Cao G, Liu Q. Initial soil responses to experimental warming in two contrasting forest ecosystems, Eastern Tibetan Plateau, China: nutrient availabilities, microbial properties and enzyme activities. Applied Soil Ecology, 2010, 46(2): 291-299.

[7]Kennedy A C, Smith K L. Soil microbial diversity and the sustainability of agricultural soils. Plant and Soil, 1995, 170(1): 75-86.

[8]Hoogmoed M, Cunningham S C, Baker P, Beringer J, Cavagnaro T R. N-fixing trees in restoration plantings: Effects on nitrogen supply and soil microbial communities. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2014, 77: 203-212.

[9]Boyle S A, Yarwood R R, Bottomley P J, Myrold D D. Bacterial and fungal contributions to soil nitrogen cycling under Douglas fir and red alder at two sites in Oregon. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2008, 40(2): 443-451.

[10]Bini D, Santos C A D, Bouillet J P, de Morais Gonçalves J L, Cardoso E J B N.EucalyptusgrandisandAcaciamangiumin monoculture and intercropped plantations: Evolution of soil and litter microbial and chemical attributes during early stages of plant development. Applied Soil Ecology, 2013, 63: 57-66.

[11]罗达, 史作民, 唐敬超, 刘世荣, 卢立华. 南亚热带乡土树种人工纯林及混交林土壤微生物群落结构. 应用生态学报, 2014, 25(9): 2543-2550.

[12]Wang H, Liu S R, Wang J X, Shi Z M, Lu L H, Zeng J, Ming A G, Tang J X, Yu H L. Effects of tree species mixture on soil organic carbon stocks and greenhouse gas fluxes in subtropical plantations in China. Forest Ecology and Management, 2012, 300: 4-13.

[13]Chen T H, Chiu C Y, Tian G L. Seasonal dynamics of soil microbial biomass in coastal sand dune forest. Pedobiologia, 2005, 49(6): 645-653.

[14]王卫霞, 史作民, 罗达, 刘世荣, 卢立华. 南亚热带3种人工林土壤微生物生物量和微生物群落结构特征. 应用生态学报, 2013, 24(7): 1784-1792.

[15]Vance E D, Brookes P C, Jenkinson D S. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 1987, 19(6): 703-707.

[16]Brookes P C, Landman A, Pruden G, Jenkinson D S. Chloroform fumigation and the release of soil nitrogen: a rapid direct extraction method to measure microbial biomass nitrogen in soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 1985, 17(6): 837-842.

[17]Wu J, Joergensen R G, Pommerening B, Chaussod R, Brookes P C. Measurement of soil microbial biomass C by fumigation-extraction-an automated procedure. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 1990, 22(8): 1167-1169.

[18]鲁如坤..土壤农业化学分析方法. 北京: 中国农业科技出版社, 2000.

[19]Bossio D A, Scow K M. Impacts of carbon and flooding on soil microbial communities: phospholipid fatty acid profiles and substrate utilization patterns. Microbial Ecology, 1998, 35(3/4): 265-278.

[20]Liu L, Zhang T, Gilliam F S, Gundersen P, Zhang W, Chen H, Mo J M. Interactive effects of nitrogen and phosphorus on soil microbial communities in a tropical forest. PloS One, 2013, 8(4): e61188.

[21]Myers R T, Zak D R, White D C, Peacock A. Landscape-level patterns of microbial community composition and substrate use in upland forest ecosystems. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 2001, 65(2): 359-367.

[22]Zhang C, Liu G B, Xue S, Xiao L. Effect of different vegetation types on the rhizosphere soil microbial community structure in the loess plateau of China. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 2013, 12(11): 2103-2113.

[23]Liu X, Lindemann W C, Whitford W G, Steiner R L. Microbial diversity and activity of disturbed soil in the northern Chihuahuan Desert. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2000, 32(3): 243-249.

[24]Moore-Kucera J, Dick R P. PLFA profiling of microbial community structure and seasonal shifts in soils of a Douglas-fir chronosequence. Microbial Ecology, 2008, 55(3): 500-511.

[25]白震, 何红波, 解宏图, 张明, 张旭东. 施肥与季节更替对黑土微生物群落的影响. 环境科学, 2008, 29(11): 3230-3239.

[26]Rogers B F, Tate III R L. Temporal analysis of the soil microbial community along a toposequence in Pineland soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2001, 33(10): 1389-1401.

[27]Lipson D A, Schadt C W, Schmidt S K. Changes in soil microbial community structure and function in an alpine dry meadow following spring snow melt. Microbial Ecology, 2002, 43(3): 307-314.

[28]牛佳, 周小奇, 蒋娜, 王艳芬. 若尔盖高寒湿地干湿土壤条件下微生物群落结构特征. 生态学报, 2011, 31(2): 474-482.

[29]Unger I M, Kennedy A C, Muzika R M. Flooding effects on soil microbial communities. Applied Soil Ecology, 2009, 42(1): 1-8.

[30]Singh S, Ghoshal N, Singh K P. Variations in soil microbial biomass and crop roots due to differing resource quality inputs in a tropical dryland agroecosystem. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2007, 39(1): 76-86.

[31]Wang F M, Li Z A, Xia H P, Zou B, Li N Y, Liu J, Zhu W X. Effects of nitrogen-fixing and non-nitrogen-fixing tree species on soil properties and nitrogen transformation during forest restoration in southern China. Soil Science & Plant Nutrition, 2010, 56(2): 297-306.

[32]Rhoades C, Binkley D. Factors influencing decline in soil pH in HawaiianEucalyptusandAlbiziaplantations. Forest Ecology and Management, 1996, 80(1/3): 47-56.

[33]Yamashita N, Ohta S, Hardjono A. Soil changes induced byAcaciamangiumplantation establishment: Comparison with secondary forest andImperatacylindricagrassland soils in South Sumatra, Indonesia. Forest Ecology and Management, 2008, 254(2): 362-370.

[34]Finzi A C, Canham C D, Van Breemen N. Canopy tree-soil interactions within temperate forests: species effects on pH and cations. Ecological Applications, 1998, 8(2): 447-454.

[35]Clark J S, Campbell J H, Grizzle H, Acosta-Martìnez V, Zak J C. Soil microbial community response to drought and precipitation variability in the Chihuahuan Desert. Microbial Ecology, 2009, 57(2): 248-260.

[36]Liu W X, Jiang L, Hu S J, Li L H, Liu L L, Wan S Q. Decoupling of soil microbes and plants with increasing anthropogenic nitrogen inputs in a temperate steppe. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2014, 72: 116-122.

[37]Rousk J, Brookes P C, Bååth E. Contrasting soil pH effects on fungal and bacterial growth suggest functional redundancy in carbon mineralization. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2009, 75(6): 1589-1596.

[38]Nilsson L O, Bååth E, Falkengren-Grerup U, Wallander H. Growth of ectomycorrhizal mycelia and composition of soil microbial communities in oak forest soils along a nitrogen deposition gradient. Oecologia, 2007, 153(2): 375-384.

[39]Bååth E, Anderson T H. Comparison of soil fungal/bacterial ratios in a pH gradient using physiological and PLFA-based techniques. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2003, 35(7): 955-963.

[40]Bååth E. Growth rates of bacterial communities in soils at varying pH: a comparison of the thymidine and leucine incorporation techniques. Microbial Ecology, 1998, 36(3/4): 316-327.

[41]Bååth E, Arnebrant K. Growth rate and response of bacterial communities to pH in limed and ash treated forest soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 1994, 26(8): 995-1001.

[42]Högberg M N, Bååth E, Nordgren A, Arnebrant K, Högberg P. Contrasting effects of nitrogen availability on plant carbon supply to mycorrhizal fungi and saprotrophs-a hypothesis based on field observations in boreal forest. New Phytologist, 2003, 160(1): 225-238.

[43]Fernández-Calvio D, Bååth E. Growth response of the bacterial community to pH in soils differing in pH. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2010, 73(1): 149-156.

[44]Högberg M N, Högberg P, Myrold D D. Is microbial community composition in boreal forest soils determined by pH, C-to-N ratio, the trees, or all three?. Oecologia, 2007, 150(4): 590-601.

[45]Bardgett R D, Frankland J C, Whittaker J B. The effects of agricultural management on the soil biota of some upland grasslands. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 1993, 45(1/2): 25-45.

[46]Rousk J, Brookes P C, Bååth E. The microbial PLFA composition as affected by pH in an arable soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2010, 42(3): 516-520.

[47]Kemmitt S J, Wright D, Goulding K W T, Jones D L. pH regulation of carbon and nitrogen dynamics in two agricultural soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2006, 38(5): 898-911.

Characteristics of soil microbial community structure in two young plantations ofCastanopsishystrixandErythrophleumfordiiin subtropical China

HONG Pizheng1, LIU Shirong1,*, WANG Hui1, YU Haolong2

1KeyLaboratoryofForestEcologyandEnvironmentalSciencesofStateForestryAdministration,InstituteofForestEcology,EnvironmentandProtection,ChineseAcademyofForestry,Beijing100091,China2ExperimentalCenterofTropicalForestry,ChineseAcademyofForestry,Pingxiang532600,China

subtropical China; N-fixing tree species; non-N-fixing tree species; soil microbial community

国家科技支撑计划项目(2012BAD22B01)

2014-11-24; 网络出版日期:2015-10-30

Corresponding author.E-mail: liusr@caf.ac.cn

10.5846/stxb201411242328

洪丕征,刘世荣,王晖,于浩龙.南亚热带红椎和格木人工幼龄林土壤微生物群落结构特征.生态学报,2016,36(14):4496-4508.

Hong P Z, Liu S R, Wang H, Yu H L.Characteristics of soil microbial community structure in two young plantations ofCastanopsishystrixandErythrophleumfordiiin subtropical China.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2016,36(14):4496-4508.