中晚期宫颈癌的临床特点与筛查策略分析

李小毛 黄珊瑜 杨越波 叶青剑 叶敏娟

·临床研究论著·

中晚期宫颈癌的临床特点与筛查策略分析

李小毛黄珊瑜杨越波叶青剑叶敏娟

目的分析中晚期宫颈癌的临床特点,探讨筛查策略。方法收集239例宫颈癌患者的临床资料,按其FIGO分期分组,其中早期(Ⅰa1~Ⅰb2期)组91例(38.1%)、中晚期(Ⅱ~Ⅳ期)组148例(61.9%),比较2组的临床特征。结果早期组患者发病年龄为(46.8±10.3)岁,高峰年龄段为40~50岁,中晚期组发病年龄为(52.6±9.9)岁,高峰年龄段为45~60岁,2组发病年龄比较差异有统计学意义(P<0.001)。早、中晚期组患者中,年龄≤35岁患者分别占14.3%、4.1%,2组比较差异有统计学意义(P<0.01);绝经后发病者分别占30.8%、52.7%,2组比较差异有统计学意义(P<0.01)。早期组患者中城市户籍、农村户籍分别占44.0%、56.0%,中晚期组为17.6%、82.4%,2组比较差异有统计学意义(P<0.001);早期组患者文化程度为小学及以下、中学、大专及以上分别占31.9%、50.5%、17.6%,中晚期组患者相应为49.3%、45.3%、5.4%,2组比较差异亦有统计学意义(P<0.01)。中晚期组患者临床首发症状为接触性阴道流血者比例低于早期组患者(26.4%、45.1%,P<0.01)。结论与早期宫颈癌患者相比,中晚期宫颈癌患者具有发病年龄晚、绝经后发病比例高、农村户籍所占比例高、文化水平相对低、不易被早发现的特点。因此,为了早期发现宫颈癌变,改善宫颈癌患者预后及生活质量,需要合理分配社会医疗资源,适当调整政府政策,更应关注文化水平低的农村中年妇女。

中晚期宫颈癌;临床特点;筛查策略

宫颈癌是女性常见生殖系统恶性肿瘤。据统计,我国宫颈癌发病率为13/100 000,死亡率为3/100 000[1]。近年来,随着宫颈癌三阶梯防癌筛查的普及,宫颈癌的早诊、早治成为可能,大大降低宫颈癌的发病率,但中晚期宫颈癌所占比例及其病死率仍居高不下,不容乐观。中晚期宫颈癌患者治疗后的生活质量、健康状况评分差,且有更高比例的焦虑障碍[2-3]。为此,本研究回顾性分析我院近年收治的中晚期宫颈癌患者病例,并与同期收治的早期宫颈癌患者作对照,探讨中晚期宫颈癌的临床特点,分析子宫颈防癌筛查重点人群,提高筛查的社会经济效益,以期降低中晚期宫颈癌发病率、病死率,改善宫颈癌患者的预后。

对象与方法

一、研究对象

2013至2015年我院收治的经病理活组织检查(活检)首次确诊的宫颈癌患者239例,按其FIGO分期分组,分为早期(Ⅰa1~Ⅰb2期)组91例(38.1%)、中晚期(Ⅱ~Ⅳ期)组148例(61.9%)。

二、研究方法

收集239例患者的临床资料,比较早期组与中晚期组在发病年龄、年轻(≤35岁)患者比例、户籍、文化程度、临床表现及症状持续时间的差异。

三、统计学处理

结 果

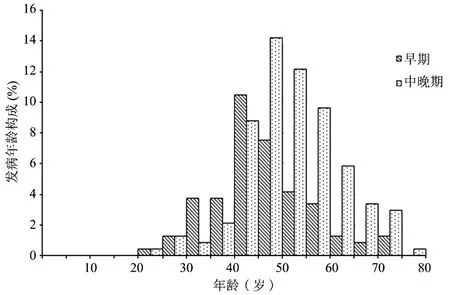

一、早期组和中晚期组宫颈癌患者的发病年龄差异

早期组患者发病年龄分布于23~75岁,高峰年龄段为40~50岁,中晚期组患者发病年龄分布于23~79岁,高峰年龄段为45~60岁(图1)。早期组患者发病年龄为(46.8±10.3)岁,中晚期组发病年龄为(52.6±9.9)岁,2组比较差异有统计学意义(t=4.372,P<0.001)。

早期宫颈癌患者中年龄≤35岁者13例(14.3%),中晚期患者中≤35岁者6例(4.1%),2组比较差异有统计学意义(χ2=8.062,P<0.01);早期宫颈癌患者中,绝经后发病者28例(30.8%),中晚期患者中,绝经后发病者78例(52.7%),2组比较差异有统计学意义(χ2=10.984,P<0.01)。

图1 早期组、中晚期组患者宫颈癌患者的发病年龄分布直方图

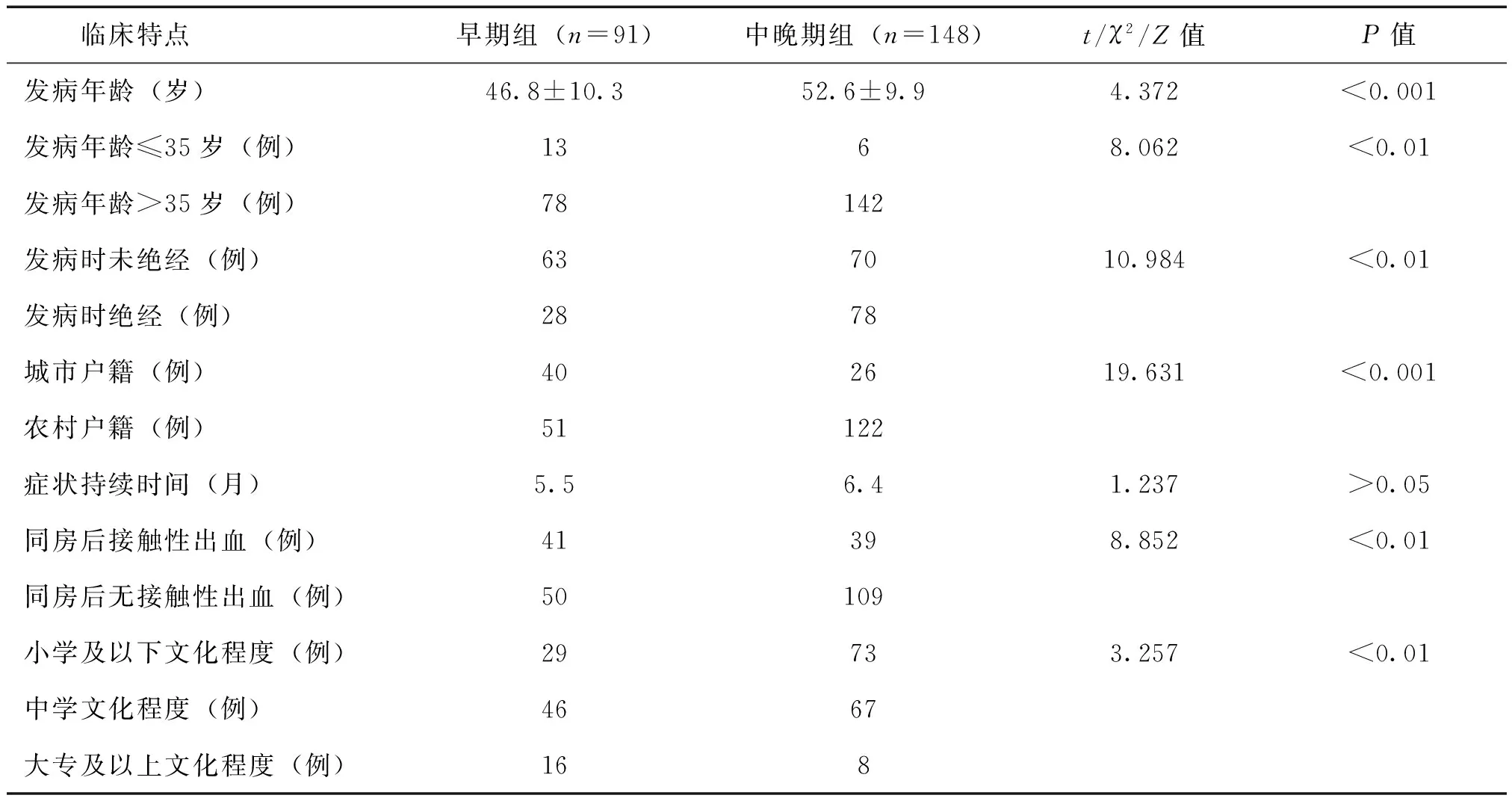

二、早期组和中晚期组宫颈癌患者的户籍差异

早期宫颈癌患者中,城市户籍、农村户籍分别为40例(44.0%)、51例(56.0%);中晚期患者中,城市户籍、农村户籍分别为26例(17.6%)、122例(82.4%),2组比较差异有统计学意义(χ2=19.631,P<0.001)。

三、早期组和中晚期组宫颈癌患者的文化程度差异

早期宫颈癌患者中,文化程度为小学及以下、中学、大专及以上分别为29例(31.9%)、46例(50.5%)、16例(17.6%);中晚期患者中,文化程度为小学及以下、中学、大专及以上分别为73例(49.3%)、67例(45.3%)、8例(5.4%),2组比较差异有统计学意义(Z=3.257,P<0.01)。

四、早期组和中晚期组宫颈癌患者的症状表现及持续时间差异

宫颈癌患者的临床症状表现多为同房后阴道流血、阴道异常流血流液、下腹痛等。早期、中晚期组患者症状持续时间分别为5.5、6.4月,2组比较差异无统计学意义(Z=1.237,P>0.05)。其中,临床首发症状为同房后阴道流血者,早期宫颈癌患者中有41例(45.1%),中晚期患者中有39例(26.4%),2组比较差异有统计学意义(χ2=8.852,P<0.01)。

表1 早期组和中晚期组宫颈癌患者的临床特点比较

讨 论

宫颈癌患者往往因同房后阴道流血就诊,当肿瘤进一步发展出现浸润生长时,可出现不规则阴道流血、排液、疼痛等症状。部分宫颈癌患者在体检被发现,此类患者多数相对早期,早期宫颈癌患者经手术治疗预后较好,因此,为早期发现宫颈病变,进行宫颈癌的筛查有其必要性。目前,宫颈癌的筛查主要是“三阶梯防癌筛查”,包括宫颈细胞学筛查、人乳头瘤状病毒(HPV)DNA检测、阴道镜下多点活检[4]。上述以细胞学检查为主的宫颈癌初筛策略,可有效降低宫颈癌的发病率[5]。然而,细胞学检查存在一定的假阳性率,HPV DNA检测在监测子宫颈病变有较高的敏感度[6]。临床上常将HPV DNA与细胞学检查联合进行宫颈癌初筛,可更加准确、早期发现子宫颈癌变[7]。阴道镜下多点活检则进一步放大病灶,利用醋酸及碘试验判断子宫颈病变范围,结合病理活检可及时、准确发现病灶[8]。

在进行宫颈癌筛查普及的同时,应强调有组织、高效地进行防癌筛查。在发达国家,政府机构组织进行的宫颈细胞学筛查项目,大大降低了宫颈癌的发病率和病死率。在宫颈癌高发病率的发展中国家地区,往往因无组织的筛查甚至是无任何筛查措施,宫颈癌未得到很好的控制[9]。以往宫颈癌发病高风险的香港、台湾、新加坡地区,因有效的宫颈癌筛查手段的普及,其宫颈癌的发病率在短期内得到很好的控制[10]。在宫颈癌发病风险较低的中东地区,因缺乏有组织宫颈癌筛查项目、宫颈癌诊断水平差,宫颈癌的发病率、病死率并没有得到相应水平的控制[11]。因此,在强调宫颈癌筛查普及的同时,进行有效的宫颈防癌筛查,才能发挥其降低宫颈癌发病率、病死率的作用,提高其社会经济价值。

本研究发现,中晚期组宫颈癌患者平均发病年龄较早期组患者大,年轻患者所占比例低,绝经后发病比例较高。该组以同房后阴道流血为首发症状表现者较早期组患者相对少,提示中晚期宫颈癌患者可能因性生活频率下降,不易自我早期发现。本研究还发现,中晚期组宫颈癌患者中农村户籍所占比例相对高、文化水平相对低。农村地区经济水平所限,卫生健康宣教和医疗设备资源相对不足,农村妇女文化程度低、保健意识不强,肿瘤被发现时相对期别较晚。

多项研究表明,世界各地宫颈癌的筛查情况有其社会人口学特征,多数地区中高薪阶层、教育水平高、持有社会保险的人群宫颈癌的筛查率较高[12]。在收入水平低下的地区,宫颈癌筛查仍不容乐观,贫困地区的女性,在诊断为宫颈癌时,往往期别较晚,且有较高的病死率[13-14]。通过对宫颈癌筛查相关知识的教育普及,能够大幅降低宫颈癌的发病率[15]。因此,为有效改善宫颈癌预后、充分发挥子宫颈防癌筛查的社会经济价值,应加强对农村地区、文化水平低的人群的筛查和宣教。我国肿瘤登记数据表明,城市地区45~50岁组宫颈癌发病率达高峰,而农村地区55~60岁组年龄段发病率达高峰,相对城市地区晚,随着年龄的增长,宫颈癌的病死率呈上升趋势,且农村地区各年龄组的病死率均高于城市地区[1]。国外学者研究也表明,农村地区宫颈癌筛查率远低于城市地区,且随着年龄的增加,浸润性宫颈癌的发生率逐渐上升,其预后也明显较差[16-17]。这与农村地区医疗卫生资源匮乏,诊疗条件低下,年长患者健康保健意识差,同房次数少,不容易被发现,导致就诊晚等有关。因此,筛查重点向农村中年妇女转移,加强农村及中年妇女对宫颈癌的认识、提高农村医疗水平,对降低宫颈癌病死率有重大意义。

在城乡地区经济、医疗水平差异较大的现状下,为充分发挥我国宫颈癌筛查的社会经济价值,降低宫颈癌的发病率、病死率,提高宫颈癌患者的预后及生活质量,需要合理分配社会医疗资源,适当调整政府政策,更应关注文化水平低的农村中年妇女。

[1]应倩,夏庆民,郑荣寿,张思维,陈万青.中国2009年宫颈癌发病与死亡分析.中国肿瘤,2013,22(8): 612-616.

[2]Distefano M, Riccardi S, Capelli G, Costantini B, Petrillo M, Ricci C, Scambia G, Ferrandina G.Quality of life and psychological distress in locally advanced cervical cancer patients administered pre-operative chemoradiotherapy.Gynecol Oncol,2008,111(1):144-150.

[3]Kirchheiner K, Nout RA, Czajka-Pepl A, Ponocny-Seliger E, Sturdza AE, Dimopoulos JC, Dörr W, Pötter R. Health related quality of life and patient reported symptoms before and during definitiveradio(chemo)therapy using image-guided adaptive brachytherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer andearly recovery-a mono-institutional prospective study.Gynecol Oncol,2015,136(3):415-423.

[4]卞美璐,马莉.宫颈癌的预防.新医学,2013,44(3): 201-202.

[5]Peirson L, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Ciliska D, Warren R. Screening for cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Syst Rev, 2013,2:35.

[6]Wang JL, Yang YZ, Dong WW, Sun J, Tao HT, Li RX, Hu Y.Application of human papillomavirus in screening for cervical cancer and precancerous lesions. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev,2013,14(5):2979-2982.

[7]Noventa M, Ancona E, Saccardi C, Litta P, D'Antona D, Nardelli GB, Gizzo S.Could HPV-DNA test solve the dilemma about sentinel node frozen section accuracy in early stagecervical cancer? Hypothesis and rationale.Cancer Invest,2014,32(5):206-207.

[8]杨越波,李小毛,黄敏,彭其才,刘穗玲,马琳. 阴道镜在宫颈病变诊断中的价值.齐齐哈尔医学院学报,2003,24(8): 849-850.

[9]Sankaranarayanan R, Budukh AM, Rajkumar R. Effective scr-eening programmes for cervical cancer in low- and middle-income developing countries. Bull World Health Organ,2001,79(10):954-962.

[10]Tay SK, Ngan HY, Chu TY, Cheung AN, Tay EH. Epidemiology of human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer and future perspectives in HongKong, Singapore and Taiwan.Vaccine,2008,6 (Suppl 12):M60-M70.

[11]Khorasanizadeh F, Hassanloo J, Khaksar N, Mohammad Taheri S, Marzaban M, H Rashidi B, Akbari Sari A, Zendehdel K.Epidemiology of cervical cancer and human papilloma virus infection among Iranian women-analyses ofnational data and systematic review of the literature.Gynecol Oncol,2013,128(2):277-281.

[12]Sicsic J, Franc C.Obstacles to the uptake of breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screenings: what remains to be achievedby French national programmes? BMC Health Serv Res,2014,14:465.

[13]Han MA, Choi KS, Lee HY, Jun JK, Jung KW, Kang S, Park EC.Performance of papanicolaou testing and detection of cervical carcinoma in situ in participants oforganized cervical cancer screening in South Korea.PLoS One, 2012,7(4):e35469.

[14]Kim CW, Lee SY, Moon OR.Inequalities in cancer incidence and mortality across income groups and policy implications in SouthKorea.Public Health,2008,122(3):229-236.

[15]Caster MM, Norris AH, Butao C, Carr Reese P, Chemey E, Phuka J, Turner AN. Assessing the acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness of a tablet-based cervical cancer educationalIntervention.J Cancer Educ,2015 Dec 5.[Epub ahead of print].

[16]Douine M, Roué T, Lelarge C, Adenis A, Thomas N, Nacher M.Screening for cervical cancer in French Guiana: screening rates from 2006 to 2011.Bull Soc Pathol Exot,2015,108(5):355-359.

[17]Darlin L, Borgfeldt C, Widén E, Kannisto P.Elderly women above screening age diagnosed with cervical cancer have a worse prognosis.Anticancer Res,2014,34(9):5147-5151.

(本文编辑:林燕薇)

Analysis of clinical characteristics and screening strategies in advanced cervical cancer

Li Xiaomao, Huang Shanyu, Yang Yuebo, Ye Qingjian, Ye Minjuan.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology,the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University,Guangzhou 510630, China Corresponding author, Li Xiaomao, E-mail: tigerlee777@163.com

ObjectiveTo analyze the clinical characteristics of advanced cervical cancer, and to explore new screening strategy. Methods239 cases of patients with cervical cancer were collected, according to the FIGO staging. 91 patients (38.1%) were in early stage (FIGO Ⅰa1-Ⅰb2) of cervical cancer, while 148 patients (61.9%) were in advanced stage (FIGO Ⅱ-Ⅳ), the clinical features between the two groups were compared. ResultsThe onset age was (46.8 ± 10.3) years old in the early group, whose peak ages were at the range of 40 to 50 years old, the age of onset in advanced group was (52.6 ± 9.9) years old, whose peak ages were at the range of 45 to 60 years old, there was significant difference between the two groups (P<0.001). In early and advanced group, age less than or equal to 35 years old accounted for 14.4% and 4.1%, respectively (P<0.01); and after postmenopause, the incidence of onset were 30.8% and 52.7%, respectively, there was statistically difference between the two groups (P<0.01). In early group of patients, household registration of urban and rural accounted for 44% and 56%, respectively, while in advanced stage group of patients, which accounted 17.6% and 82.4%, respectively, there were statistically difference between the two groups (P<0.001). The education level of elementary school or below, secondary school, college or above accounted for 31.9%, 50.5% and 17.6% respectively in early group, and in advanced stage group of patients which education degree were corresponding 49.3%, 45.3% and 5.4% respectively, the difference was also statistically significant between the two groups (P<0.01). Contact bleeding as first symptom in the advanced groups was found in 26.4% patients, significantly lower than 45.1% in the early group(P<0.01). ConclusionsCompared with patients in early stage cervical cancer, advanced cervical cancer patients have characteristics of late onset ages, high proportion in postmenopausal women, high proportion of rural household registration, relatively low level of culture and difficult finding. Thus, in order to find early cervical cancer, and improve the prognosis and life quality of patients, it is of great necessary to reasonably reallocate social resources, appropriately adjust government policy, and more attention should be given to the low culture level of rural middle-aged women.

Advanced cervical cancer; Clinical characteristics; Screening strategy

10.3969/j.issn.0253-9802.2016.08.008

510630 广州,中山大学附属第三医院妇科

,李小毛,E-mail: tigerlee777@163.com

2016-03-04)