杉木根系对不同磷斑块浓度与异质分布的阶段性响应

邹显花, 吴鹏飞, 贾亚运, 马 静, 马祥庆*

(1国家林业局杉木工程技术研究中心, 福建福州 350002; 2福建农林大学林学院, 福建福州 350002)

杉木根系对不同磷斑块浓度与异质分布的阶段性响应

邹显花1,2, 吴鹏飞1,2, 贾亚运1, 马 静1, 马祥庆1,2*

(1国家林业局杉木工程技术研究中心, 福建福州 350002; 2福建农林大学林学院, 福建福州 350002)

【目的】对杉木根系在异质供磷(P)条件下的觅磷行为进行动态监测,探讨磷斑块的浓度与其异质分布对杉木根系觅磷行为的影响。【方法】以福建漳平五一国有林场的半同胞杉木家系为试验材料,利用垂直异质供磷装置,设置KH2PO40 mg/kg(缺磷,P0)、4 mg/kg(低磷,P4)、16 mg/kg(正常供磷,P16)和30 mg/kg(高磷,P30)4个磷浓度斑块,将其按照不同顺序垂直排列构建异质供磷处理。在生长50、100、150 d时,进行3次破坏性取样,测定不同阶段不同异质供磷处理下杉木根系形态、生物量及觅磷效率的变化,进行杉木根系生长及觅磷行为的动态观测。【结果】杉木根系表现出阶段性的觅磷策略: 1)当杉木根系处于表层缺磷或低磷斑块时,通过根系的增生向供磷量更高的斑块觅磷,根系增生促进了缺磷或低磷斑块根系的干物质积累,但其根系含磷量较低; 至处理中期,表层缺磷处理的根系从缺磷斑块生长至低磷斑块后,杉木根系受低磷胁迫持续大量增生; 而当表层低磷处理的根系从低磷斑块生长至高磷斑块后,根系在高磷斑块内大量增生,且促进了根系磷养分的吸收及干物质的积累; 处理末期,当高磷斑块置于最底层时,其斑块内的根系生长量、 干物质积累量及根系含磷量均明显较大。2)当杉木根系处在表层高磷斑块时,根系初期仅在供磷量较高的表层生长,其根系生长量与干物质积累量均低于表层供磷量较低的处理,但其根系含磷量却显著大于表层供磷量较低的处理; 处理中期及末期,表层的根系生长量、 干物质积累量及根系含磷量均显著大于其他层次,且表层充足供磷处理的根系向地生长速度最快。【结论】异质供磷条件下,当杉木根系处在缺磷或低磷斑块时,主要通过根系的大量增生来寻觅磷养分; 当杉木根系处在高磷斑块时,在初期致力于斑块磷养分的吸收之后,表层根系大量增生,且根系的磷养分吸收和干物质积累显著大于其他层次,同时提高根系向地生长速度。

杉木; 根系; 养分异质性; 觅磷行为

植物生长必需的资源在自然界分布具有明显异质性[1],如水分、 CO2、 光和矿质养分等在空间上的分布均呈斑块状[2]。其中,土壤养分空间异质性在自然生态系统普遍存在[3]。Ettma和Wardle[4]将养分空间异质性定义为养分在土壤空间结构上的变化,即在空间上分布不均匀或随机分布的聚合养分斑块。近年来,植物对土壤有效性资源空间异质性的反应,及对其觅食机制的研究已逐步成为生态学研究的热点之一。为最大限度地获取养分,植物必须通过根系不断生长来发掘土壤中富养区域,根系一系列形态和生理响应为植物获取斑块内部的养分提供了保证[5]。目前,根系在养分富集斑块内的增生现象已得到普遍证实[6-7]。根系对于富养斑块的响应一般包括根系伸长[8-9]、 细根直径变小[10]、 比根长增加[11-12]、 分枝角减小节间距缩短促使侧根数量增加[13]等一系列变化。然而,也有研究报道在异质养分条件下植物根系并未对养分斑块作出增生响应[14-15]。关于早熟禾(Poapratensis)[16]、 云杉(Piceaasperata)[17]、 欧洲山杨 (Populustremuloides)[18]的研究甚至证实贫养斑块的根系生长量大于富养斑块。杉木(Cunninghamialanceolata)在磷(P)养分异质条件下的响应机制研究也得出类似结论。 吴鹏飞等[19]研究发现磷饥饿环境下磷高效基因型杉木的根表面积和根体积显著大于正常供磷的斑块。马雪红等[20]关于杉木对异质供养环境的适应策略研究中同样发现3个不同家系的根系均在贫养斑块大量增生,且贫养斑块根系的磷含量比富养斑块高。

植物根系形态对空间异质性的反应不仅与植物种类有关,而且受斑块属性、 营养元素种类及养分总体供应状况等的影响[21]。由于根系生长环境的复杂性及根系研究方法和定量分析手段的局限性,有关异质养分条件下林木根系觅养行为的研究多由静态条件取得,对于解释植物根系具体是如何适应并利用异质养分条件存在一定的局限性。王剑等[5]对养分异质条件下马尾松(Pinusmassoniana)觅养行为的研究表明,马尾松在拓殖斑块养分初期主要依靠侧根的生成和延长,在拓殖一段时期之后除依靠新生侧根的生成外还依靠须根数量和须根密度增加来开拓异质养分环境。可见,不同时间阶段植物根系觅养的策略并不相同。

杉木是我国南方重要用材林造林树种之一,南方森林土壤有效磷缺乏已成为杉木人工林生产力的重要影响因子之一[22]。磷在土壤中的移动性差,且易被吸附和固定,土壤中磷素分布的异质性表现得尤为明显[23]。本研究采用自主设计的试验装置构建垂直异质供磷环境,通过3次破坏性模拟试验实现杉木根系生长及觅磷行为的动态过程观测,探讨磷斑块浓度、 分布方式及斑块持续性等属性对杉木根系觅磷行为的影响,进一步揭示杉木根系搜寻利用异质分布磷养分的获取机制和觅磷能力,这对于深入理解杉木根系对养分异质性的响应机制,提高养分利用效率具有重要的理论与实践意义。

1 材料与方法

1.1试验材料

试验材料为福建省漳平五一国有林场杉木无性系种子园按单系采种培育的半同胞1号家系苗。供试苗木在林场温室内培育5个月,温室平均气温20.3℃,相对湿度78%。供试苗木生长势均一、 根系完整、 无病害,平均地径0.19 cm,平均苗高4.95 cm。苗木移植之前在沙床上缓苗1个月。

1.2试验装置

采用课题组自主设计的试验装置(图1),设置垂直异质磷环境模拟的盆栽试验。选用口径为18 cm、 高32 cm的圆形聚乙烯塑料盆作为盆栽容器,培养基质为进行脱磷处理后的干净河沙(有效磷含量<0.01 mg/kg)。每盆分为4层,层次间距为4 cm,每层间隔为用琼脂涂抹均匀、 孔径为2 mm的玻璃纤维网(养分不能通过,主根、 基根均能顺利穿透)隔离,在试验装置上端填充5 cm 厚的干净河沙作为缓冲层,将供试杉木幼苗的根系洗净处理后植入缓冲层。分别在自盆底4 cm、 8 cm、 12 cm和16 cm处间隔90°钻一注射孔用于营养液及水分的供应,并用锡箔纸覆盖,以免液体流失。

图1 垂直异质供磷处理装置Fig.1 Design pot for the heterogeneous P supply in the vertical direction

1.3试验设计

1.3.1 构建异质供磷处理设置缺磷(KH2PO4)(0 mg/kg,P0)、 低磷(4 mg/kg,P4)、 正常供磷(16 mg/kg,P16)和高磷(30 mg/kg,P30)[24]4个供磷浓度的斑块,构建异质磷环境。为模拟自然土壤环境中不同浓度磷斑块在土层中的分布方式,本研究共设4个异质供磷处理(表1),V1处理中不同斑块的供磷量由表层往下逐渐升高; 而V4处理随着土层的加深,斑块中的供磷量逐渐降低; 在确定V1与V4处理排列方式的基础上,为实现4个不同磷斑块在分布层次中的两两相邻关系,且在各处理中的同一层次均不重复分布,设置了V2处理和V3处理的P斑块排列方式。试验共4个处理,每个处理重复9次。为探讨养分斑块的持续性对杉木根系觅磷行为的影响,采用破坏性取样,即在试验过程中分别在50d、 100d和150d对每个处理的苗木各收获3盆。

表1 不同异质供磷处理的各层次供应KH2PO4含量

1.3.2 营养液及水分供应采用KH2PO4作为磷源,由于在各异质供磷环境中不均等的施加KH2PO4导致供K+含量不等,因此在试验过程中通过调节营养液中KCl的含量来调节各处理斑块的K+含量。试验中所用的营养液大量元素采用Hoagland配方,微量元素采用Amon配方[25](表2),利用0.1 mol/L HCl和0.1 mol/L NaOH溶液调节营养液的pH值至5.5。

表2 营养液中其他养分含量

1.4测定项目和方法

2011年4月22日进行杉木试验苗移植,分别在6月14日、 8月4日和9月24日分3期进行苗木收获,以观测在不同处理阶段根系对异质供磷环境适应的动态变化过程。苗木分地上部和根系分别收获。地下部收获时,将不同异质处理装置从垂直方向剖开,小心散开各层河沙,对根系进行分层收获。用水清洗根系,再用蒸馏水漂洗干净,利用加拿大WinRHIZO根系分析系统对杉木根系长度、 表面积、 体积及直径进行定量分析。根系生物量采用烘干法测定,根系含磷量采用钼锑抗比色法测定[26]。

利用磷分配量表征杉木根系的觅磷效率,即植物从土壤介质中获得磷的能力, 磷分配量(mg)= 磷含量×干物质积累量[27]。

试验数据用Microsoft Excel 2007和 SPSS 11.5软件进行处理和统计分析,采用OriginPro 8.5软件绘图。

2 结果与分析

2.1磷斑块异质处理方式对杉木根系形态及生长的影响

处理初期(50 d),不同异质供磷处理条件下杉木根长、 根表面积及根体积的增量存在显著差异(图2,上)。第一层供磷量较低的V1处理和V2处理中杉木根系已伸展至第二层,且第一层根系的根长、 根表面积及根体积增量显著大于第二层(P<0.05)。而第一层供磷量较高的V3处理和V4处理根系仅在第一层大量生长。处理初期,当根系处于低磷斑块时,可促进根系向下生长,而表层斑块含磷量较高时,根系则在这一斑块内大量增生。

处理中期(100 d),V4处理中杉木根系已生长至第四层,表层供磷量充足的异质供磷处理可促进根系的向地生长,根系向地增生较快速(图2,中)。V4处理第一层的根系根长、 根表面积、 根体积增量均显著大于其他层次。V1和V3处理也表现为表层的根系生长增量显著大于第二层(P<0.05)。V1处理根系从表层缺磷斑块生长至第二层低磷斑块后,因第二层斑块中同样受到低磷胁迫,表层缺磷斑块中的根系继续大量增生觅磷。而V2处理则表现为第二层的根长、 根表面积、 根体积增量显著大于第一层,V2处理的根系从低磷斑块生长至高磷斑块后,根系在高磷斑块内大量增生,表层低磷斑块根系的增长则减缓。

处理末期(150 d),不同异质供磷处理条件下杉木根长、 根表面积及根体积的增量总体上呈现一致的变化规律(图2,下)。不同处理杉木根系均已伸展至第四层斑块,且在供磷量较大的斑块分布较多的根系。V1处理的第四层斑块的根长、 根表面积及根体积的增量最大,显著大于其他斑块的根系生长量(P<0.05)。V2处理中同样表现为第四层的根系生长量最大。表层供磷量较大的V3和V4处理则表现为表层的根系生长量显著大于其他层次。不同异质供磷处理均表现为当正常供磷或充足供磷斑块置于最底层或表层时,其斑块内的根系生长增生明显。

图2 初期、中期和末期不同异质供磷处理根系形态指标增量的比较Fig.2 Increment comparison of the root morphology index of different treatments affected by heterogeneous P supply at different stages [注(Note): 不同处理第一层至第四层供磷量依次为V1 (P0、 P4、 P16、 P30),V2(P4、 P30、 P0、 P16),V3(P16、 P0、 P30、 P4),V4(P30、 P16、 P4、 P0) P concentration from the first to the forth layer were showed in turn as P0,P4,P16 and P30 for V1; P4,P30,P0 and P16 for V2; P16,P0,P30 and P4 for V3; and P30,P16,P4 and P0 for V4. 柱上不同小写字母表示同一处理不同斑块间的差异达5%显著水平Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences (P<0.05) among different patches in the same treatment at the 5% level.]

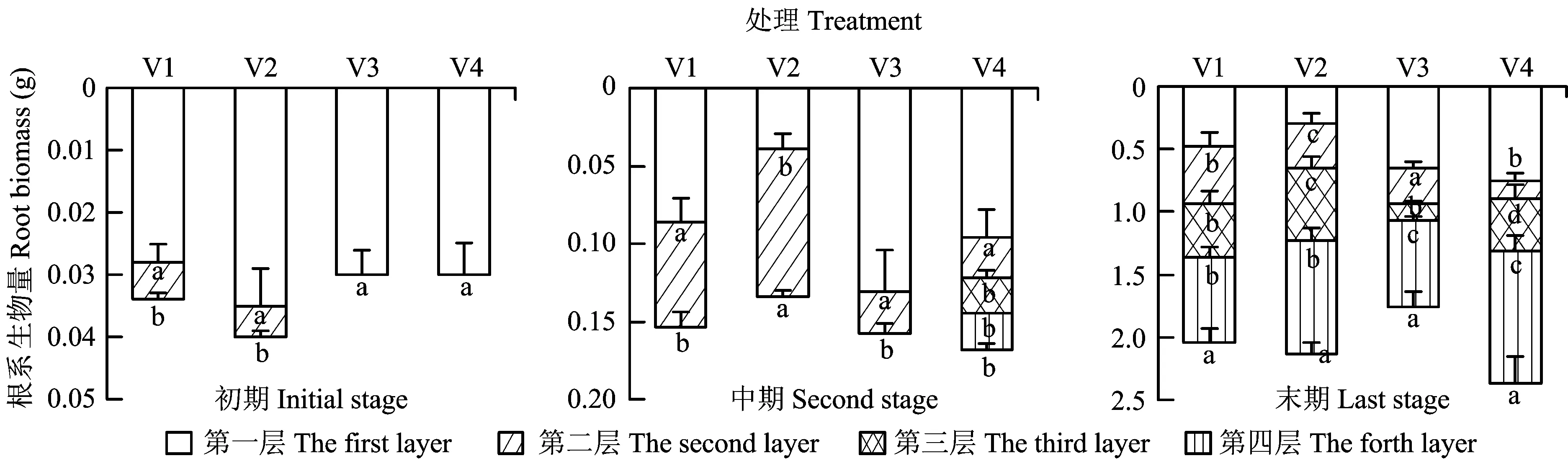

图3 初期、中期和末期不同异质供磷处理根系生物量增量的比较Fig.3 Increment comparison of the root biomass of different treatments affected by heterogeneous P supply at different stages [注(Note): 不同处理供磷量第一层至第四层分布规律依次为V1 (P0、 P4、 P16、 P30),V2(P4、 P30、 P0、 P16),V3(P16、 P0、 P30、 P4),V4(P30、 P16、 P4、 P0) P concentrations of different treatments from the first layer to the forth layer showed as P0,P4,P16 and P30 for V1; P4,P30,P0 and P16 for V2; P16,P0,P30 and P4 for V3; and P30,P16,P4 and P0 for V4.柱上不同小写字母表示同一处理不同斑块间的差异达5%显著水平Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences (P<0.05) among different patches in the same treatment at the 5% level.]

图4 初期、 中期和末期不同异质供磷处理根系磷分配量的比较 Fig.4 Comparison of the root P allocation of different treatments with heterogeneous P supply at different stages[注(Note): 不同处理供磷量第一层至第四层分布规律依次为V1 (P0、 P4、 P16、 P30),V2(P4、 P30、 P0、 P16),V3(P16、 P0、 P30、 P4),V4(P30、 P16、 P4、 P0) P concentrations of different treatments from the first layer to the forth layer showed as P0,P4,P16 and P30 for V1; P4,P30,P0 and P16 for V2; P16,P0,P30 and P4 for V3; and P30,P16,P4 and P0 for V4.柱上不同小写字母表示同一处理不同斑块间的差异达5%显著水平Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences (P<0.05) among different patches in the same treatment at the 5% level.]

2.2磷斑块异质处理方式对杉木根系生物量的影响

不同处理时期不同异质供磷处理的杉木根系生物量增量存在显著差异,且与根系形态指标的变化规律基本一致(图3)。处理初期,V1和V2处理的根系生物量增量均为第一层显著大于第二层(P<0.05)。从总生物量增量来看,V3和V4处理的总生物量增量显著小于V1和V2处理; 处理中期,V3和V4处理表层根系生物量增量均显著大于其他层次,V1处理第一层的根系生物量增量显著大于第二层,V2处理则表现为第二层的根系生物量显著大于第一层; 处理末期,V1与V2处理均表现为第四层的根系生物量增量显著大于其他层次。V3处理则第一层和第四层的根系生物量增量差异不显著,但显著大于第二和第三层。V4处理第四层的根系生物量增量最大,而第二层和第三层则明显小于其他层次。

2.3磷斑块异质处理方式对杉木根系觅磷效率的影响

不同处理时期不同异质供磷处理的杉木根系磷分配量存在显著差异(图4)。处理初期,V1和V2处理的根系磷分配量均表现为第二层显著大于第一层(P<0.05),这与根系形态和生长量以及生物量增量呈现的规律完全相反。不同于根系形态及生物量增量的是,表层供磷量较大的V4和V3处理表层根系的磷分配量显著大于V1和V2处理; 处理中期,V3和V4处理第一层的根系磷分配量显著大于其他层次。V1处理第一层与第二层的根系磷分配量差异未达到显著水平,V2处理第二层的根系磷分配量则显著大于第一层; 处理末期,V1处理第四层的根系磷分配量与第一层差异不显著,V2处理第四层的根系磷分配量则显著大于其他层次,V3与V4处理均表现为第一层的根系磷分配量显著大于其他层次。处理末期,与根系的生长量相似,不同异质供磷处理也表现为当正常供磷或充足供磷斑块置于最底层或表层时,其斑块内根系的磷分配量具有明显优势。

3 讨论

在异质供磷条件下,处理初期,当杉木根系处于缺磷或低磷斑块时,其根系大量增生,但并未提高根系的磷吸收量而仅是提高了根系的干物质产量。由此,杉木根系启动觅磷机制[28],促进根系向下延伸寻觅磷养分。Jackson等[29]研究认为当低磷土壤中生长的根系进入磷富集区时,根系能够快速地做出反应,增强对磷的吸收能力。本研究发现,杉木根系由低磷斑块伸展至高磷斑块后,根系在高磷斑块内大量增生,低磷斑块根系的增长则减缓,高磷斑块内根系的磷吸收能力明显提高。而当根系由缺磷斑块伸长至同样受到低磷胁迫的低磷斑块后,缺磷斑块中的根系继续大量增生觅磷,缺磷斑块与低磷斑块的根系磷含量差异却并不显著。由此可以推测,在表层根系受到极度缺磷胁迫时,第二层与表层斑块的根系之间发生了养分的转移。已有研究表明,体内养分转移是植物的一种重要养分保存机制,实现了体内养分的高效利用,使植物有效地保持生产力,以增强在生境中的竞争力[30]。对于克隆植物的研究表明,当相互联结的克隆分株处于资源水平不同的小生境中时,克隆分株间将存在一个资源水平梯度。该梯度的存在将改变固有的源—汇关系,使从某一资源丰富的小生境中吸收的资源,能够为该小生境以外的其他相连克隆分株共享[31]。Pierret等[32]也认为磷利用效率较高的植物,更多通过增加磷在植物体内的高效转运和合理利用提高其磷效率。

当杉木根系初期处在高磷斑块中时,杉木根系仅在表层高磷斑块中大量生长,其根系生长总量及干物质积累量均小于处于表层缺磷或低磷斑块的处理,但高磷斑块中的杉木根系含磷总量却显著高于缺磷或低磷斑块,由此推测,当根系处在含磷量较高的斑块时根系致力于磷养分的吸收而非浪费资源用于短期的生长。De Kroon等[33]也认为,当土壤养分更新速率很慢时,将养分浓度吸收到一个很低水平并延长根的寿命会比在一个偶然遇到的养分斑块中大量增殖根更加重要。本研究发现,初期根系养分的吸收促进了后期表层高磷斑块内根系的增生及干物质的积累,同时提高了根系向地生长速度。Robinson[34]认为土壤中养分离子移动性低的情况下,根系快速生长并在养分富集区域增生的能力能显著发挥。对磷素这种在土壤中有效性低,移动性很小的营养元素,植物根系对磷的获取主要依赖于根系的生长和根形态的改变[35],通过增加根系在磷富集区的分配比例、 根系长度、 根系表面积、 根体积等来占据更多的土壤体积,增加了与移动性差的土壤磷素的接触面积,补偿了其余根系由于无法获取磷对植物生长消耗的影响,提高对磷的获取能力[36]。本研究中,在不同处理根系均已分布至第四层的处理末期,不同处理均表现为根系在位于最底层或是表层的磷富集区大量增生,且根系的大量增生促进了斑块内根系的磷养分吸收和干物质积累。表层供磷量较低的处理通过根系的伸展觅磷,在最底层的高磷斑块大量富集,表层供磷量较高的处理根系则在表层高磷斑块分布增生。

4 结论

本研究对异质供磷条件下杉木根系觅磷行为的动态变化进行了研究,发现异质供磷条件下,磷斑块浓度、 斑块分布方式及斑块持续性等属性对杉木根系觅磷行为存在明显影响,杉木根系对不同的磷斑块浓度及斑块分布方式存在阶段性的觅磷策略。当杉木根系处在缺磷或低磷斑块时,主要通过根系的大量增生来寻觅磷养分; 当杉木根系处在高磷斑块时,初期致力于斑块磷养分的吸收,后期表层根系的生长、 磷养分吸收和干物质积累均显著高于其他层次。不同异质供磷条件下,当高磷斑块置于最底层或表层时,其斑块内根系的生长量、 含磷量及干物质的积累具有明显优势。因破坏性试验的局限性,本研究对于杉木根系觅磷策略的时间精确性把握不够,在今后的研究工作中应进一步提高试验技术条件。此外,本研究主要阐明杉木根系对于异质磷环境的表型适应性反应,对于内在生理调控机制有待进一步深入研究。

[1]陈玉福, 董鸣. 生态学系统的空间异质性[J]. 生态学报, 2003, 23(2): 346-352.

Chen Y F, Dong M. Spatial heterogeneity in ecological systems[J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2003, 23(2): 346-352.

[2]Pinno B D, Wilson S D. Fine root response to soil resource heterogeneity differs between grassland and forest[J]. Plant Ecology, 2013, 214(6): 821-829.

[3]李洪波, 薛慕瑶, 林雅茹, 申建波. 土壤养分空间异质性与根系觅食作用: 从个体到群落[J]. 植物营养与肥料学报, 2013,19(4): 995-1004.

Li H B, Xue M Y, Lin Y R, Shen J B. Spatial heterogeneity of soil nutrients and root foraging: from individual to community[J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer, 2013, 19(4): 995-1004.

[4]Ettema C H, Wardle D A. Spatial soil ecology[J]. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 2002, 17(4): 177-183.

[5]王剑, 周志春, 金国庆, 等. 马尾松种源在异质养分环境中的觅养行为差异[J]. 生态学报, 2007, 27(4): 1350-1358.

Wang J, Zhou Z C, Jin G Q,etal. Differences of foraging behavior between provenances ofPinusmassonianain heterogeneous nutrient environment[J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2007, 27(4): 1350-1358.

[6]杨青, 张一, 周志春, 等. 异质低磷胁迫下马尾松家系根构型和磷效率的遗传变异[J]. 植物生态学报, 2011,35(12): 1226-1235.

Yang Q, Zhang Y, Zhou Z C,etal. Genetic variation in root architecture and phosphorus efficiency in response to heterogeneous phosphorus deficiency inPinusmassonianafamilies[J]. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology, 2011, 35(12): 1226-1235.

[7]Zhang Y, Zhou Z C, Yang Q. Genetic variations in root morphology and phosphorus efficiency ofPinusmassonianaunder heterogeneous and homogeneous low phosphorus conditions[J]. Plant and Soil, 2013, 364(1-2): 93-104.

[8]Walk T C, Jaramillo R, Lynch J P. Architectural tradeoffs between adventitious and basal roots for phosphorus acquisition[J]. Plant and Soil, 2006, 279(1-2): 347-366.

[9]He Y, Liao H, Yan X L. Localized supply of phosphorus induces root morphological and architectural changes of rice in split and stratified soil cultures[J]. Plant and Soil, 2003, 248(1-2): 247-256.

[10]Hu Y F, Ye X S, Shi L,etal. Genotypic differences in root morphology and phosphorus uptake kinetics inBrassicanapusunder low phosphorus supply[J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 2010, 33(6): 889-901.

[11]Ao J H, Fu J B, Tian J,etal. Genetic variability for root morph-architecture traits and root growth dynamics as related to phosphorus efficiency in soybean[J]. Functional Plant Biology, 2010, 37(4): 304-312.

[12]Wang X R, Pan Q, Chen F X,etal. Effects of co-inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and rhizobia on soybean growth as related to root architecture and availability of N and P[J]. Mycorrhiza, 2011, 21(3): 173-181.

[13]Hill J O, Simpson R J, Moore A D,etal. Morphology and response of roots of pasture species to phosphorus and nitrogen nutrition[J]. Plant and Soil, 2006, 286(1-2): 7-19.

[14]Bliss K M, Jones R H, Mitchell R J,etal. Are competitive interactions influenced by spatial nutrient heterogeneity and root foraging behavior?[J]. The New Phytologist, 2002, 154(2): 409-417.

[15]Wijesinghe D K, John E A, Beurskens S, Hutchings M J. Root system size and precision in nutrient foraging: responses to spatial pattern of nutrient supply in six herbaceous species[J]. Journal of Ecology, 2001, 89(6): 972-983.

[16]Hodge A, Stewart J, Robinson D,etal. Root proliferation, soil fauna and plant nitrogen capture from nutrient-rich patches in soil[J]. New Phytologist, 1998, 139(3): 479-494.

[17]Proe M F, Millard P. Effect of P supply upon seasonal growth and internal cycling of P in Sitka spruce [Piceasitchensis(Bong.)Carr.] seedlings[J]. Plant and Soil, 1995, 168-169(1): 313-317.

[18]Rothstein D E, Zak D R, Pregitzer K S, Curtis P S. Kinetics of nitrogen uptake byPopulustremuloidesin relation to atmospheric CO2and soil nitrogen availability[J]. Tree Physiology, 2000, 20(4): 265-270.

[19]Wu P F, Ma X Q, Tigabu M,etal. Root morphological plasticity and biomass production of two Chinese fir clones with high phosphorus efficiency under low phosphorus stress[J]. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 2011, 41(2): 228-234.

[20]马雪红, 周志春, 张一, 金国庆. 杉木不同家系对异质养分环境的适应性反应差异[J]. 植物生态学报, 2008, 32 (1): 189-196.

Ma X H, Zhou Z C, Zhang Y, Jin G Q. Differences of adaptability amongCunninghamialancelatavarieties to heterogeneous nutrient environment[J]. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology, 2008, 32 (1): 189-196.

[21]王庆成, 程云环. 土壤养分空间异质性与植物根系的觅食反应[J]. 应用生态学报, 2004,15(6): 1063-1068.

Wang Q C, Cheng Y H. Response of fine roots to soil nutrient spatial heterogeneity[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2004, 15(6): 1063-1068.

[22]俞新妥. 中国杉木研究进展(2000-2005) I. 杉木生理生态研究综述[J]. 福建林学院学报, 2006, 26 (2): 177-185.

Yu X T. A summary of the studies on Chinese fir in 2000-2005 I. The research development on physiological ecology of Chinese fir[J]. Journal of Fujian College of Forestry, 2006, 26 (2): 177-185.

[23]孙桂芳, 金继运, 石元亮. 土壤磷素形态及其生物有效性研究进展[J]. 中国土壤与肥料, 2011, (2): 1-9.

Sun G F, Jin J Y, Shi Y L. Review of the forms and biological effectiveness of phosphorus in soil[J]. Soil and Fertilizer Sciences in China, 2011, (2): 1-9.

[24]梁霞, 刘爱琴, 马祥庆, 等. 不同杉木无性系磷素特性的比较[J]. 植物生态学报, 2006, 30 (6): 1005-1011.

Liang X, Liu A Q, Ma X Q,etal. Comparison of the phosphorus characteristics of different Chinese fir clones[J]. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology, 2006, 30 (6): 1005-1011.

[25]Arnon D I. Microelements in culture-solution experiments with higher plants[J]. American Journal of Botany, 1938, 31(1): 322-325.

[26]LY/T 1270-1999.中华人民共和国林业行业标准 (森林土壤分析方法)[S].

LY/T 1270-1999. Analysis methods of forest soil in forestry industry standard of China[S].

[27]曹靖, 张福锁. 低磷条件下不同基因型小麦幼苗对磷的吸收和利用效率及水分的影响[J]. 植物生态学报, 2000, 24 (6): 731-735.

Cao J, Zhang F S. Phosphorus uptake and utilization efficiency in seedlings of different wheat genotypes as influenced by water supply at low soil phosphorus availability[J].Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology, 2000, 24 (6): 731-735.

[28]吴鹏飞. 磷高效利用杉木无性系适应环境磷胁迫的机制研究[D]. 福州: 福建农林大学博士学位论文, 2009.

Wu P F. Adaptation mechanism of Chinese fir clones with high phosphorus-use-efficiency to environmental phosphorus stress[D]. Fuzhou: PhD Dissertation of Fujian Agriculture and Forest University, 2009.

[29]Jackson R B, Manwaring J H, Caldwell M M. Rapid physiological adjustment of roots to localized soil enrichment[J]. Nature, 1990, 344(6261): 58-60.

[30]吴鹏飞,马祥庆. 植物养分高效利用机制研究进展[J]. 生态学报, 2009, 29 (1): 427-437.

Wu P F. Research advances in the mechanisms of high nutrient use efficiency in plants[J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2009, 29 (1): 427-437.

[31]Luo D, Qian Y Q, Han L,etal. Phenotypic responses of a stoloniferous clonal plantBuchloedactyloidesto scale-dependent nutrient heterogeneity[J]. Plos One, 2013, 8(6): e67396.

[32]Pierret A, Moran C J, Doussan C. Conventional detection methodology is limiting our ability to understand the roles and functions of fine roots[J]. The New Phytologist, 2005, 166(3): 967-980.

[33]De Kroon H, Mommer L, Nishiwaki A. Root competition: towards a mechanistic understanding[J]. Root Ecology, 2003, 168: 215-234.

[34]Robinson D. Resource capture by localized root proliferation: why do plants bother?[J]. Annals of Botany, 1996, 77(2): 179-186.

[35]Yano K, Kume T. Root morphological plasticity for heterogeneous phosphorus supply inZeamaysL.[J]. Plant Production Science, 2005, 8(4): 427-432.

[36]Li H G, Shen J B, Zhang F S, Lambers H. Localized application of soil organic matter shifts distribution of cluster roots of white lupin in the soil profile due to localized release of phosphorus[J]. Annals of Botany, 2010, 105(4): 585-593.

Periodical response of Chinese fir root to the phosphorus concentrations in patches and heterogeneous distribution in different growing stages

ZOU Xian-hua1,2, WU Peng-fei1,2, JIA Ya-yun1, MA Jing1, MA Xiang-qing1,2*

(1StateForestryAdministrationEngineeringResearchCenterforChineseFir,Fuzhou350002,China;2CollegeofForestry,FujianAgricultureandForestryUniversity,Fuzhou350002,China)

【Objectives】This study aimed to dynamic investigation of the effect of inhomogeneous P supply on the P foraging behavior of Chinese fir roots.【Methods】 The tested materials in the pot experiment was Chinese fir clone belongs to half-sib family, which were cultivated in Wuyi state-owned forest in Zhangping County, Fujian Province. Phosphorous patches with KH2PO4of 0, 4, 16 and 30 mg/kg were prepared, and the patches were loaded in four different orders inside a column to make four treatments of heterogeneous P supply. The fir seedlings were destructively samples at the 50, 100 and 150 d after transplanted into the treatment pots. The root morphology, biomass and P acquisition efficiency were measured.【Results】 It exhibits different adaptive strategies of Chinese fir roots in response to different P concentrations and patches distribution in stages. 1)The roots grew in patches with P deficiency or low P supply proliferate for foraging P in other patches with higher P supply at the initial. The root proliferation contributes to the dry matter accumulation but not the P content of roots in P deficiency or low P patches. Roots continue to proliferate in the patch with no P supply due to low P stress when roots grew from the P deficiency patch to the P-poor patch. However, the increase was slowed down when roots grew from the P-poor patch to the P-rich patch, resulting proliferation in the P-rich patch, and the proliferation results in the increase of P absorption and dry matter accumulation. At the last stage, the P-rich patches have higher roots increment, dry matter accumulation and P content when they are at the bottom-most layers. 2)Roots of the treatments with P-rich supply in the first layer only grow in the P-rich patches at the initial stage. The roots increment and dry matter accumulation of these patches are all higher than those of the treatments with P deficiency or low P supply in the first layer, while the roots’ P content shows an opposite result. At the second and last stages, the roots increment, dry matter accumulation and P contents in the surface layers are all higher than those in the other layers. In addition, the treatment with the most P supply in the surface layer has the fastest speed to downward grow. 【Conclusions】 P deficiency or low P supply result in root proliferation which contributes to foraging P. Roots in the surface layer with P-rich supply are committed to P absorption at the initial stage. Then roots proliferate in the surface layer, and the P absorption, dry matter accumulation and downward growth of roots are higher than those in the other layers.

Chinese fir; root; nutrient heterogeneity; foraging behavior for phosphorus

2015-02-03接受日期: 2015-03-24网络出版日期: 2015-08-19

国家自然科学基金(31370619,U1405211); 国家林业局杉木工程技术研究中心孵化基金(6213c0111); 福建农林大学重点项目建设专项(6112C035J)资助。

邹显花(1987—), 女, 福建三明人, 博士研究生, 助理研究员, 主要从事林木养分利用方面的研究。

Tel: 0591-83780261, E-mail: zhouxianhua111@163.com。*通信作者 Tel: 0591-83780261, E-mail: lxymxq@126.com

S791.27; Q945.12

A

1008-505X(2016)04-1056-08