Studying the Real Forces Driving Innovation Is Vital for China

By JOHN ROSS

INNOVATION is rightly seen as key to Chinas economic future. But because it is so crucial it is vital to study the real facts regarding the forces determining innovation – rather than myths. These will also determine the impact of Chinas innovation on the global economy.

A Specifi c Feature of Chinas Growth

Economic fundamentals illustrate clearly why innovation is so critical for China. Analyzing in terms of classical “growth accounting,” an economys supply side inputs are capital, labor, and “total factor productivity” (TFP)– the latter being all growth not explained by increases in capital and labor. More precise versions add “intermediate products” – the inputs of one economic sector into another produced by increasing division of labor and specialization. Innovations effects are measured as part of TFP.

In most economies the most powerful forces of economic development are, in descending order of importance, intermediate products, fixed investment, labor inputs, and TFP. This applies during periods of high innovation. For example, during the U.S. “information technology revolution” from 1977 to 2000, on average 52 percent of U.S. economic growth was due to inputs of intermediate products, 24 percent to fi xed investment, 15 percent to labor inputs, and nine percent to TFP.

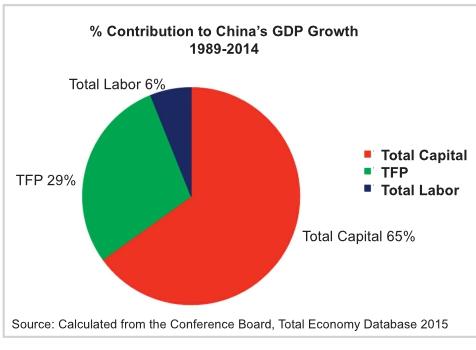

But China has a pattern of growth different from most economies. Labor inputs play a smaller role due to the one child policy. Studies confi rm that the biggest factor in Chinas economic development was growth of inter- mediate product, as with all major economies. But taking other contributions to growth, the fi gure shows that over the period 1989-2014 a mere six percent of Chinas growth came from increase in labor inputs compared to 65 percent from fixed investment and 29 percent from TFP. The much smaller contribution of labor inputs to Chinas growth than in most economies will be accentuated as Chinas working-age population begins to decline.

Some ameliorative measures can be taken regarding Chinas demographic challenge, such as raising the retirement age and improving education and skills, but these cannot entirely overcome the trend of Chinas declining working-age population. Therefore, Chinas economic development will depend, in descending order of importance, on intermediate products, capital investment and TFP. Growth of labor inputs will play a negligible/negative role. Innovation, a determinant of TFP, therefore, plays an even more critical role in China than in other economies.

Innovation and Capital Investment

Turning to the interaction between these different factors of production, it is crucial for China to understand that innovation and capital investment are not alternative or counterposed sources of economic development. The two are interrelated given that innovation typically has to be embodied in new capital equipment.

This was clearly seen in the most famous recent international wave of innovation – the U.S. information and communications technology (ICT)/Internet revolution. In 1980, the year before introduction of the modern personal computer, U.S. annual productivity growth was 1.2 percent – taking a fi ve-year average to remove the effects of business cycle fl uctuations. By 2014 U.S. productivity growth was still only 1.2 percent. Therefore 34 years of revolutionary technological developments in the Internet and ICT by themselves led to no increase in U.S. productivity – clearly showing that such advances are insufficient to lead to productivity increases.

But during one phase of the Internet and ICT revolution U.S. economic efficiency sharply increased. In the period leading to 2003 U.S. annual productivity growth reached its highest level in half a century – 3.6 percent.This rise in U.S. economic productivity was explained by a huge surge in U.S. fixed investment. U.S. investment rose from 19.8 percent of GDP in 1991 to 23.1 percent of GDP in 2000, fell slightly after the “dot com” bubbles collapse, and then reached 22.9 percent in 2005. The majority of this investment was in ICT.

For the U.S. to reap the benefits of innovation, an extremely high level of capital investment, embodying these innovations, was therefore required. The lesson is that for future success Chinas innovation also has to be accompanied by a high level of capital investment. Alongside its developing strength in new sectors China will retain its strength in infrastructure and other investment intensive industries.

The Key Form of Innovation for China

Economic fundamentals also determine the decisive form of innovation for China – and its main competitive advantage in the global economy in the immediate period. In principle there are two ways as an economys productivity increases that this can translate into increased competitive advantage:

? The same product can be produced at a cheaper price.

? The price of a product can remain the same and a superior product can be produced.

However, which of these strategies is more effective is related to a countrys economic development level. The most advanced economies, which by definition are at the technological frontier, can introduce improved or new products. As they are introducing new products they can have a competitive strategy of “keep the same price, improve the product” – or even better, “introduce an entirely new product.” This is the process known as “product innovation” and is classically exemplified by Apple.

But China, as with all developing countries, will by definition be behind the technological frontier in the majority of economic sectors. It is therefore utopian to believe China will be able to carry out such “product innovation”as its main short- or medium-term policy – this would require China being at the technological frontier with the ability to expand it. Economic fundaments determine that Chinas strategy in the coming period must be “cost innovation” – use not of low wages but of technology, managerial strength, logistical skills, and other forms of innovation to reduce costs. This is the essential strategy pursued by Chinas most successful international firms such as Wanxiang and Huawei. Their high quality/lower cost products in turn revolutionize other countries industries – the excellent value of Indian or Middle Eastern telecom services, for example, is directly due to Huaweis products.

Chinas R&D

Turning to the factors which determine innovation, a romantic myth is sometimes put forward that innovation is due to “start-ups in garages.” In reality large firms and the state carry out far more R&D than small companies – such fundamental innovations as the transistor or laser were created by large firms. Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator of the Financial Times, also noted when reviewing Mazzucatos now classic study The Entrepreneurial State: “Innovation depends on bold entrepreneurship. But the entity that takes the boldest risk and achieves the biggest breakthroughs is not the private sector; it is the… state… ”

The U.S. National Science Foundation funded the algorithm that drove Googles search engine. Early funding for Apple came from the U.S. governments Small Business Investment Company. Moreover, “All the technologies which make the iPhone ‘smart are also state-funded... the Internet, wireless networks, the global positioning system, microelectronics, touch screen displays and the latest voice-activated SIRI personal assistant.” Apple put this together, brilliantly. But it was gathering the fruit of seven decades of state-supported innovation.

Even regarding “start-ups” it is a myth that these come from isolated “garages.” The start-ups in the U.S. Silicon Valley are fed by their relationship with one of the worlds largest research institutions – Stanford University. As Acs put it in his classic study Innovation and the Growth of Cities:

“When one asked the question, ‘What makes Silicon Valley unique, the discussion usually comes back to one great institution – Stanford University. It is conventional wisdom that Silicon Valley and Route 128 owe their status as centers of commercial innovation and entrepreneurship to their proximity to Stanford and MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology).”

Similarly, if less developed, small start-up hubs in relation to huge universities exist in other countries. China is attempting to create similar high technology clusters, and the huge increase in Chinas allocation of resources to R&D can nurture these. A massive expansion and strengthening of Chinas university sector is required to sustain this.

Start-ups supposedly coming from “garages” therefore do not violate the rule that “nothing comes from nothing.” As Audretsch put it in Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth:

“How are these small and frequently new firms able to generate innovative output when undertaking a generally negligible amount of investment into knowledge-generating inputs, such as R&D?... through exploiting knowledge created by expenditures on research in universities and on R&D in large corporations.”

The worlds most innovative sector, U.S. Internet industry, is determined by massive inputs from the state, huge research institutions such as Stanford University, and transforming its technological innovations into U.S. productivity growth. It is thus dependent on massive fixed capital investment. As this is in accordance with the laws of economics, Chinas innovation will not be able to follow any different path. The developments required for this will in turn reshape the global economy.