Across White Deer Plain

by+Peng+Su

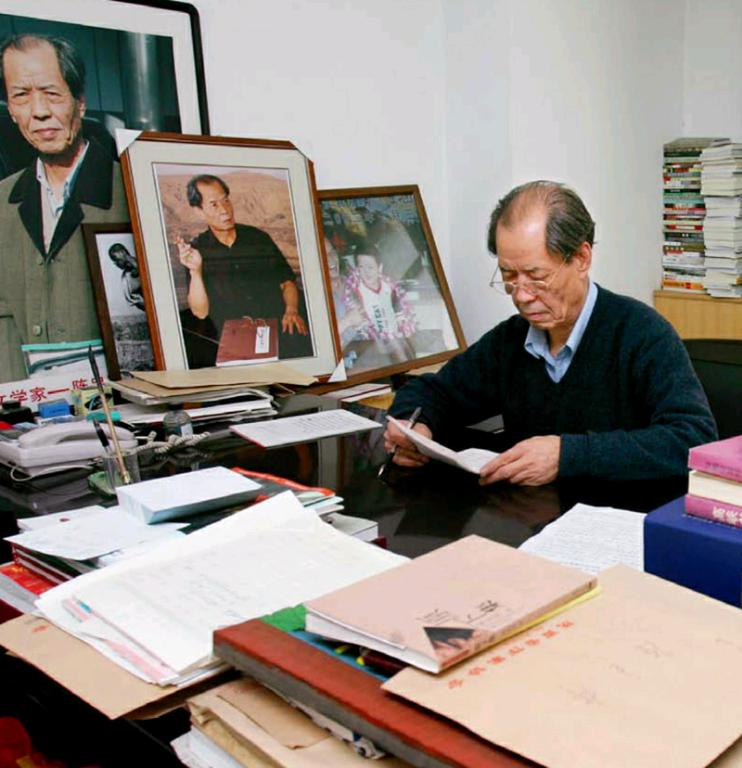

On April 29, 2016, revered Chi- nese writer Chen Zhongshi passed away in Xian, Shaanxi Province, at the age of 73. One of the most influential writers in modern China, Chen shot to stardom after the publication of White Deer Plain, a novel recounting stories across three generations of two families in Bailu (White Deer) Village in Guanzhong area, rural Shaanxi, that reflect Chinas historical changes from the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) to the 1950s. The book is considered one of the most important pieces of fiction since the founding of New China.

At the start of the book, Chen devoted an entire page to a single quote by de Balzac: “The novel carries the secret history of a nation.” And many sighed that Chen took with him part of the nations history when he left this world.

White Deer Plain

His signature work marked the turning point of Chens writing career. Prior to 1985, Chen mainly focused on rural subjects. In 1985, he completed the 80,000-character Mr. Lanpao, depicting the social structure and organization of rural China before 1949.

Mr. Lanpao (Blue Robe), the protagonist, is a representation of countryside intellectuals who endured ups and downs and suffered considerably during the countrys social transformation.

Chens investigation of the county annals of Lantian, Xianning, and Changan, Shaanxi Province, inspired White Deer Plain.

In the summer of 1986, Chen began in-depth research of Lantian County. “I gradually sketched the characters for the book, and a single-line story soon became complicated,” he later illustrated. In 1989, he dropped everything to completely devote himself to writing in the house his family had inhabited for generations.

In the early 1990s, White Deer Plain was published in Contemporary Literature, a well-known Chinese monthly digest, in two parts. It quickly drew wide attention and rave reviews from home and abroad.

The stories from the Guanzhong Plain in Shaanxi trace social changes across half a century. Three generations of families headed by Bai Jiaxuan and Lu Zilin, respectively, feud with each other against the backdrop of Chinas new-democratic revolution, the Japanese invasion, and the War of Liberation. The families experience dramatic changes paralleling the countrys social progress.

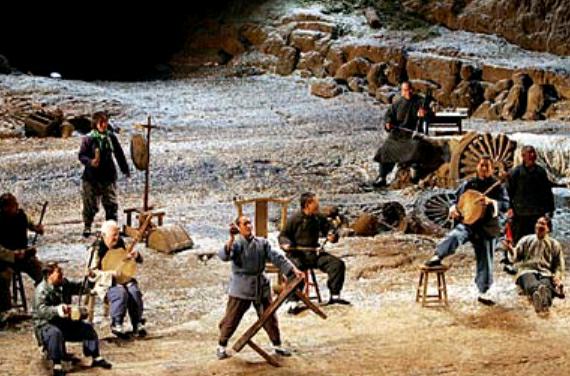

In 1997, White Deer Plain won the 4th Mao Dun Literature Awards, one of the top honors for literary achievement in China. Over the next 20 years, its total circulation surpassed 2 million, and the book was adapted into other media including stage plays, dance dramas, and films.

Despite the books sterling reputation in Chinese literary circles and wide circulation, its 500,000 Chinese characters and complicated plot were seen as difficult to understand by the Western world. But critics often compare Chen Zhongshi with Mo Yan, the first Chinese writer to win the Nobel Prize.

One of the greatest features of Mo Yans work is imagination. Mo is an expert at exaggeration, disguising his own stories behind myths and folktales – overt expressions with strong flavor of Western realism, which could be why he is more accepted by Western readers.

Chen Zhongshi, on the contrary, expressed himself with authentic Chinese tone, as exemplified by White Deer Plain. He interpreted traditional Confucianism, patriarchal systems, and morality and ethics through stories set against big-picture historical and cultural backdrops, which could be difficult to follow after translation. Today, White Deer Plain has been translated into various Asian languages, such as Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Mongolian, but in terms of European languages, only French.

National Epic

However, the features that are most confusing to Western readers are likely exactly why the book is considered such an authentic rural Chinese story: the historical and cultural background as well as Chinese methods of expression.

“A writer should focus on the land beneath his feet – not only today but yesterday,” asserted Chen in an interview. “The words we write should be rich in history, culture, and national spirit. Ive learned from foreign literature how to better examine our lives and express myself. The heart of my stories is always Chinese tradition and culture.”

Of the worlds many literary giants, Chen was most inspired by Alejo Carpentier(1904-1980), a Cuban writer who endeavored to work within the modernist school of Western countries but failed. Instead, Carpentier found great success with The Kingdom of This World, a story about his hometown in Haiti. After reading that work, Chen made up his mind to stand with his own nation and “open” traditional realism.

Through the stories of the Bai and Lu families living on the Weihe Plain of Shaanxi, the author depicts life in rural areas, the foundation of the country, during an era of great transformation and evolution of Chinas patriarchal society and familial culture. Instead of laying out a timeline, he showcased a typical village where gains and losses are linked to the rise and fall of the country.

“The real history of modern China is not only the revolution, warfare, and natural disasters recorded in history books,” asserted Chen. “Rather, they are in the lives of people who experienced these affairs.”Thats why White Deer Plain is considered to have such profound historical value.“Chen Zhongshi worked hard to dig deeper into the complicated relationship between man and history, culture and life, from various angles that together compose a birds-eye view of Chinese history,” commented Zhu Zhai, a literary critic and a research fellow from the Institute of Literature under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

A Life of Writing

In 1962, Chen Zhongshi failed the college entrance examination and went to work in a village school, teaching and writing during his spare time. “In 1973, a magazine began to hunt for experienced writers throughout the province,” recalled Li Xing, a famous literary critic. Li became acquainted with Chen later after a mutual friend referred him: “I know someone called Chen Zhongshi who lives in Baqiao District on the eastern suburbs 15 kilometers from Xian. His prose was published in a newspaper in the 1960s.” That statement launched Chens professional writing career.

During his later years, Chen hated air travel and avoided helping anyone write a biography about himself.

“He was a heavy smoker,” revealed Xing Xiaoli, his friend and deputy editorin-chief of Novel Comment. “That was why he hated flying. He didnt like biographies because he wanted more focus on his work than his life.”

A friend once suggested that he keep writing about rural China of the last half century. Chen kept silent and never explained why he stopped.

“I think every writer experiences a zenith,” continues Li Xing. “Chen Zhongshis fell in the 1980s. His long-term experience in rural areas and the countrys implementation of economic reform and opening-up policies created great opportunity. However, he was most familiar with the traditional countryside. He could hardly comprehend the changes of the 1990s: global markets and commercialization.”