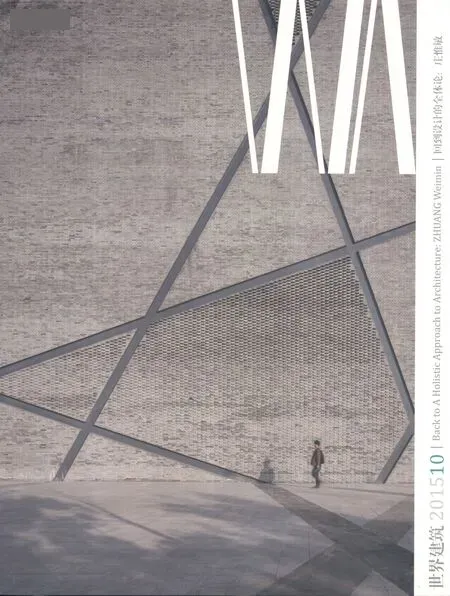

专业分工时代的全体论方法

张利

专业分工时代的全体论方法

张利

工业时代之前的建筑学,无论是在西方还是在东方,都被默认以全体论的方式存在:思想与操作的连贯,学理与工法的融汇,知识与技能的共轭,自然科学、哲学、神学、文学、美术、音乐、手工艺的精通;阿尔伯蒂、帕拉第奥、丢勒、鲁班……建筑师实乃全才之谓,“哲匠”之范。

工业化的不断演进带来的专业分工的不断加剧,戏剧化膨胀的浩瀚知识体系使得“全才”不再可能存在。文艺复兴式的通科达人的最近闪现也要追溯到19世纪黄金时代的俄罗斯了。在高度信息化与全球化的今天,任何人在一个生命跨度内实现对所有学科的般般通晓都是不可能的,更不用说样样精通了。

虽然全体论的超人不复存在,但打破学科分野、桥接理论与实践领域的全体论方法仍然是可行的,特别对于建筑学这种知识边界模糊、思维模式混杂、与当下的专工时代格格不入的“蹩脚”学科来说,它甚至还是行之有效的、维系建筑对文明积极作用的途径。20世纪,在欧洲城市化与战后重建的最富挑战性阶段,曾经出现了以格罗庇乌斯、塞尔特、巴奇马、凡·艾克等为代表的现代全体论者,他们拒绝机械的现代专业分工,跨越在理论、实践与教育、城市与建筑、人文与科技之间,坚实地推动了人工环境贡献于普遍意义的人的提升的进程。

庄惟敏教授是在当代中国艰巨的城市化进程中,坚持采用全体论方法的本土建筑师代表。一方面,作为在文革之后接受高等教育的最早一代中国建筑师的领军团队成员,他与几位同侪一样,担负着以建筑设计带动社会进程的时代责任;另一方面,作为身兼名牌建筑学院院长与重要国有设计院院长职位的极少个例之一,他又不可避免地面临在理论、实践与教育之间架接桥梁的义务。有趣的是,在他的家庭教育与成长背景的作用下,这种全体论方法更多呈现为一种无心插柳的自然结果,而不是一种有意而为的强制角色。

在其理论上,庄惟敏教授把目光聚焦到鲜为创作型建筑师所关注的实证主义问题——建筑提供有效空间服务的寿命——即建筑策划问题上。在20余年前,庄惟敏就提出,对于公共利益的维护,建筑(特别是大型公共建筑)任务书的制定可能比建筑的形式风格更为重要。在今天,我们在经历了极速城市化之后,逐渐认清文明进展的差异关键在软件的优劣而非硬件的有无,这确实与庄惟敏早期提出的论点不谋而合。庄惟敏教授的长期坚持也使建筑策划逐步从无人问津的“非建筑”问题,变成了受到当今中国建筑学界关注的重要问题之一。

在其实践上,庄惟敏教授拒绝任何建筑类型或个性化手法的标签——即使这在快餐式建筑文化消费的时代,意味着职业建筑写手与商业建筑策展人的噩梦。庄惟敏的建筑可以在华山游客中心中体现为俯首自然的地景化,也可以在清华科技园大厦中体现为超高密度开发的自我救赎,也可以在南极科考站中体现为非物质化的临时性,更可以在中国美术馆加建中体现为息声循形的消隐。在大多数建筑师追求个人风格营销的时代,庄惟敏似乎不无顽固地坚持着“不同环境、不同课题必将引向不同建筑答案”的传统的建筑因地制宜原则。

在其教育上,庄惟敏教授有意回避政论式的宏大叙事,以及惊人的教育理念措辞,而是以一种包容的开放的态度,委婉地传递一个事实上的鲜明立场:建筑教育从来都是,现在也是,未来更将是关于合格的建筑师的培养。道可传,业可授,惑可解,然名不可造。是故,建筑教育乃成就建筑师之谓,非成就建筑“大师”之谓。这一脚踏实地、立足根本的务实建筑教育理念,与以成败论英雄、以建筑为扬名立腕之借的精英建筑教育理念针峰相对,在对中国当代建筑教育去向何方的争论中,扮演着关键的角色。

我们感兴趣于庄惟敏教授的全体论方法,以及他在理论、实践、教育上的融汇对于中国当代建筑与建筑教育的影响。这也是我们在今年关注文革后中国建筑师个体的《世界建筑》特辑中,聚焦于庄惟敏的原因。□

Architecture used to be holistic in the pre-industrial age, both in the East and in the West. Across the world, there was continuity in architectural thinking and operation, theory and tectonics, knowledge and skills. In architects those of Alberti, Palladio, Dueller and Lu Ban, we found individuals that were masters-of-everything. They were de facto philosopher-builders.

With industrialisation there arrived specialisation, ever more of it. the dramatic expansion of the body of knowledge totally eradicates the possibility of any master-of-everything ever again. the last flash of such human individuals is as far as 19th century Russia. In a globe of high IT today, no one can even put a finger in everything, let alone master it.

Gone are the old fashioned masters. But the holistic approach is never to die. In a murky, hybrid, incompatible-to-complete-modernspecialisation profession, such as architecture, the breaking down of knowledge boundaries, the bridging of theory and practice is still a sensible way. Under most circumstances, it is even still the only sensible way to maintain the relevance of architecture in human civilisation. In the 20th century, facing the most demanding time of urbanisation and post-war reconstruction, there have been people like Gropius, Sert, Bakema and Van Eyck who took the holistic approach and led the process of making built space for the wider good of the mankind. All of them rejected imposed specialisations. All of them carried out their individual inquiry across the fields of theory, practice and education.

Professor ZHUANG Weimin is a typical example of a contemporary Chinese architect adopting the holistic approach, trying to tackle the difficult issues of modern Chinese urbanisation. On one hand, he is a key member of the current academic leadership in Chinese architecture formed by people educated in the early post-culture-revolution years. He thus has his share of the formidable responsibility of moving the society forward through architecture. On the other hand, he is one of the very few examples of being both the dean of a prestigious architecture school and the director of a large state-owned design firm. He then must connect theory, practice and education, not least for his own sake. Interestingly, from his own family background and personal development, this holistic approach seems rather more like a natural outcome than a injected one.

In his theory, ZHUANG started to focus on the positivist subject of programming from quite early on. Over twenty years ago, he proposed that for the public good, the programming of large public buildings in China was more important than the cosmetic issues, an argument hugely doubted then, but broadly accepted today. It is after twenty years of rapid, sometime ruthless, urbanisation that China comes to the understanding of what the quality of city life is really about. With most people agreeing now that the software is more important than the hardware, ZHUANG's persistent work in the last two decades is paying off.

In his practice, ZHUANG rejects all typological or stylistic taggingeven if at a time that consumes architecture fast food, this means the nightmare of professional critics and commercial curators. In Mount Huashan Visitor Center, he makes the building like landscapes. In Science & Technology Mansion of TUS Park, he presented a self-redemption of a hyper-density commercial development. In China Antarctic Station, he tries dematerialising portability. In the Renovation of the National Art Museum of China, he demonstrates striking constraint and invisibility. When most architects today seem to be enjoying self-promoting signature styles, ZHUANG sticks with the obstinacy that architecture needs to be honest representations of different situations.

In his pedagogy, ZHUANG avoids narratives of grant scales, or rhetoric of deliberate surprises. With his well-known tolerance and open-mindedness, he maintains a simple yet strong position: architecture education has been, is and will still be about professional competence. You can teach principles, you can teach knowledge, you teach skills, but you cannot teach fame. This very practical position stands on a firm ground against the success-and-fame-orientated position of elitist architecture education. No matter what, ZHUANG's position and pedagogy plays a key role in the debate of Chinese architecture education today.

It is his holistic approach that we are interested in. It is also his own continuity in theory, practice and education that we feel excited about. It is these reasons that we have chosen ZHUANG Weimin as the subject of this year's World Architecture coverage on post-culturerevolution Chinese architects. □

庄惟敏

1962年10月生于上海,1985年清华大学建筑系本科毕业, 1992年清华大学博士毕业,获工学博士学位。

国家设计大师,国家一级注册建筑师、注册咨询师。

现任清华大学建筑学院院长、教授、博士生导师,清华大学建筑设计研究院院长、总建筑师,清华大学(2014-2019年)第十届学术委员会委员。2012年获中国建筑学会建筑教育奖,2012年获当代中国百名建筑师称号。

中国建筑学会资深会员、中国建筑学会常务理事、中国建筑学会建筑师分会副理事长、中国建筑学会建筑师分会理论与创作专业委员会副主任委员、中国勘查设计协会高等院校勘察设计分会常务理事及副会长、全国高等学校建筑学专业家教育评估委员会委员、国际建协(UIA)理事、国际建协职业实践委员会(UIA-PPC)联席主席、APEC建筑师中国监督委员会委员。

著有《建筑策划导论》《建筑设计的生态策略》《建筑设计与经济》《2009中国城市住宅发展报告》《国际建协建筑师职业实践政策推荐导则》《筑·记》《环境生态导向建筑复合表皮设计要点及工程实践》《雪域宗山》等专著,已发表学术论文100余篇。曾主持中国美术馆改造工程、世界大学生运动会游泳跳水馆、2008年奥运会国家射击馆、飞碟靶场和柔道跆拳道馆、华山游客中心、北川抗震纪念园幸福园展览馆、钓鱼台国宾馆3号楼及网球馆工程、中国国际博览中心等重大工程的设计工作。华山游客中心曾获得亚建协2014荣誉奖,金沙遗址博物馆获2014年FIDIC工程项目奖提名,2004年获英国皇家建筑师协会“多样的城市”设计竞赛大奖。设计作品多次获国家金、银、铜奖及省部级优秀设计奖,学会建筑创作金、银奖。

ZHUANG Weimin

Born in Shanghai, October 1962

B. E., School of Architecture, Tsinghua University, 1985

D. E., School of Architecture, Tsinghua University, 1992

National Design Master, National First-Class Registered Architect and Registered Consultant of China

Dean, professor and doctoral supervisor of School of Architecture, Tsinghua University; Director and chief architect of the Architectural Design & Research Institute of Tsinghua University; Member of the 10th (2014-2019) Academic Committee of Tsinghua University. In 2012, he was awarded the Architectural Education Prize by the Architectural Society of China and with the title of the Top 100 Chinese Contemporary Architects.

He is a senior member and executive councilor of the Architectural Society of China (ASC), vice chairman of the Architect Branch, ASC, vice director of the theory and Creative Work Committee of the Architect Branch , ASC, vice chairman and executive councilor of the China Exploration & Design Association, member of the National Architecture Education Evaluation Committee, councilor of International Union of Architects (UIA), president of Professional Practice Committee of UIA, and member of APEC China's Architect Project Monitoring Committee.

His work of publications include Introduction on Architecture Programming, Ecological Strategies of Architectural Design, Architectural Design and Economy, Annual Report on Urban Housing Development Report in China 2009, UIA Accord on Recommended International Standards of Professionalism in Architectural Practice, Zhu. Ji (Building and Documentation), Environmental and Ecological-Oriented Architectural Composite Envelope Design Essentials and Project Record, Dzongs in Snow Land, etc., as well as more than a hundred published academic papers. He was the chief architect of the National Art Museum of China renovation project, Swimming and Diving Center for the World Universiade, Shooting Venue, Flying Saucer Shooting Range and Judo and Taekwondo Venue of 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, Mt. Huashan Tourist Center, Happiness Hall of the Beichuan Earthquake Memorial Park, Tennis Hall of Villa 3 in Diaoyutai State Guest House, China International Exhibition Center and other major projects. Among his projects, the Mt. Huashan Tourist Center was given Honorable Mention by ARCASIA Awards of AAA 2014. And Jinsha Site Museum was shortlisted in the FIDIC Project Award 2014 in Rio, Brazil. In 2004, he was given the RIBA Diverse City Competition Prize in Beijing, China. Many of his works were given gold, silver and bronze medals of national level, distinctive prize of provincial and departmental levels, creativity prize and silver medal by the Architectural Society of China.

A Holistic Approach at a Time of Specialisation

ZHANG Li

清华大学建筑学院/《世界建筑》

2015-10-09