为自己设计:自在之喜与自在之忧

张利

为自己设计:自在之喜与自在之忧

张利

一个在历史上被接受的说法是:建筑师是建筑作品的“母亲”,业主是“父亲”。这一说法被广泛接受的原因是,它即反映了业主与建筑师在建筑作品产生过程中的密切而复杂的共生关系,又直白地指明了建筑师在其中的.相对弱势地位(这里不含有任何性别歧视的因素)。自古以来,建筑师对所承担的“母亲”这一角色有着说不尽的委屈与埋怨,虽然这一角色客观上也为建筑师的失误提供了借口。所幸的是,建筑师在两种建筑的设计上可以同时扮演“父亲”与“母亲”的角色,一是建筑师的自宅,二是建筑师自己的工作空间。我们很想知道当建筑师拥有了这样的自在角色时,他(她)们能表现出在其他设计中看不到的哪些特点。建筑师自宅在我国尚未成为主流,因此,这一期《世界建筑》的关注就集中到了建筑师的工作空间上。

建筑师自己既然拥有了最终决策权,一切都会变简单了么?一点儿也不。我们同时看到因此种自在而来的欣喜与焦虑。乔布斯在世时曾谈及与其妻选购新家洗衣机的困扰:“我们不停地研究哪种洗衣机更能充分反映我们的价值观。”也许大多数建筑师的个人价值观不像乔氏那样鲜明,但以自己对物的选择来表达自己的愿望是同样强烈的,更何况此时的“物”并不是一架简单的机器,而是一个包被自己于其中的建成环境。任何一个建筑师在提笔设计自己的工作室之前都不能回避下列问题:工作室空间需要表现我的建筑价值观么?如果不需要,我以什么来衡量、引导我的设计?而且不表现任何价值观是否本身就是一种价值观?如果需要,我的建筑价值观是什么?我又如何在一个小的工作室空间中以令人信服的方式传递我的建筑价值观,说服前来参观我工作室的其他人,特别是那些挑剔的同行?

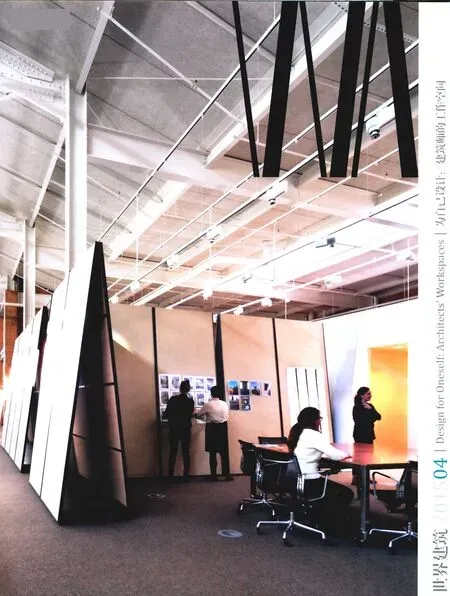

在本期所收录的实例中,回答为“不需要”的仅一个(基兰-廷伯莱克建筑师事务所)。其新的工作空间比事务所原先的工作空间更少有关于空间美学的暗示,似乎只关注效率。除去特有的大型人字背板以外,这种对表现的拒绝几乎已经成了一种自律式的拘谨。

其他的工作室案例显然都对表现建筑价值观持肯定的态度。从本质上讲,绝大多数的建筑师工作室都是对现有空间的改造(这也许是塔里埃森长年被人津津乐道的原因之一),因而建筑师的价值观也就必须通过增量(或减量)的形式加以表达。这种表达有两种主要的方式:第一种,宏观的表达方式,以对建筑空间的梳理与重构来讲述一个完整的建筑叙事,改造的增减量相对较大;第二种,微观的表达方式,以对局部建筑界面或细节的改变来形成片断化的体验暗示,改造的增减量相对较小。

显然,第一种方式在表现建筑价值观方面更为直接、强烈。这里面有对东方建筑的时间性与主客体相关性传统的整体尝试(何镜堂工作室、原作设计工作室、杨瑛工作室),有对产业空间的文化价值植入以及戏剧性交往空间营造的系统研讨(里卡多·波菲建筑师事务所、上海日清建筑设计有限公司),有对光、空气与有机体共生环境的抽象研讨(塞尔加斯-卡诺工作室、标准营造)。

A widely accepted notion is that when it comes to the authorship of architectural work, the architect is the mother, the client is the father. This notion clearly renders the close relationship between the architect and the client in the making of a work, while unmistakably suggesting the relative powerless role of the architect (no sexist view here). In history, this role not only has evoked more than enough complaint from the architect, but also has given the architect more than enough excuse for all mistakes. Fortunately, in two types of projects, the architect takes both the roles of the "father" and of the "mother" at the same time, enjoying a full control. the two types of projects are: the architect's own house and the architect's own work space. We have been keen to see what happens when architects have this type of full control. Since architects' own houses haven't been the mainstream yet in China, we focus on the architects' own working spaces in this issue.

The architect has the final say. Great. Will things become much simpler? Not really. Out of this design freedom, what we see is actually both of joy and anxiety. Steve Jobs talked about the anxiety he shared with his wife when trying to select a washing machine that correctly represents their values. An architect may not have values as unforgiving as Steve Jobs', yet the desire to represent oneself in something selected by oneself is not a single bit lower. Adding to this is that a work space is immersive and assimilating, therefore generates more sense of attachment. Any architect who is about to design his/her own work space has to answer these questions: Must my workspace reflect my architectural values? If not, what then may lead my design? (Or, is no value actually itself an value?) If yes, what are my values? How can I present these values in the work space in a convincing way, particularly to those picky fellow architects visiting my place?

In this issue, the only office that seems to have answered "no" to the first question is Kieran-Timberlake. The new workspace of this renowned office is even more neutral then their previous one. Only efficiency seems to have been addressed. Yet this neutrality comes at a price. Aside from the gable shaped large-size pin-up boards, the whole space is under a self-imposed constraint. Too much disciplined, you may argue.

Other offices answered "yes" to the first question. Generally speaking, nearly all architectwork-space projects are renovation projects to some degree. the architect's values have to been conveyed through the incremental operations applied to the space. there are two approaches to these incremental operations: the top-down one and the bottom-up one. The top-down approach tries to create a complete architectural narrative by resorting and reorganizing the whole space. The bottom-up approach tries to create fragmented moments through the microcosm treatment of parts and materials.

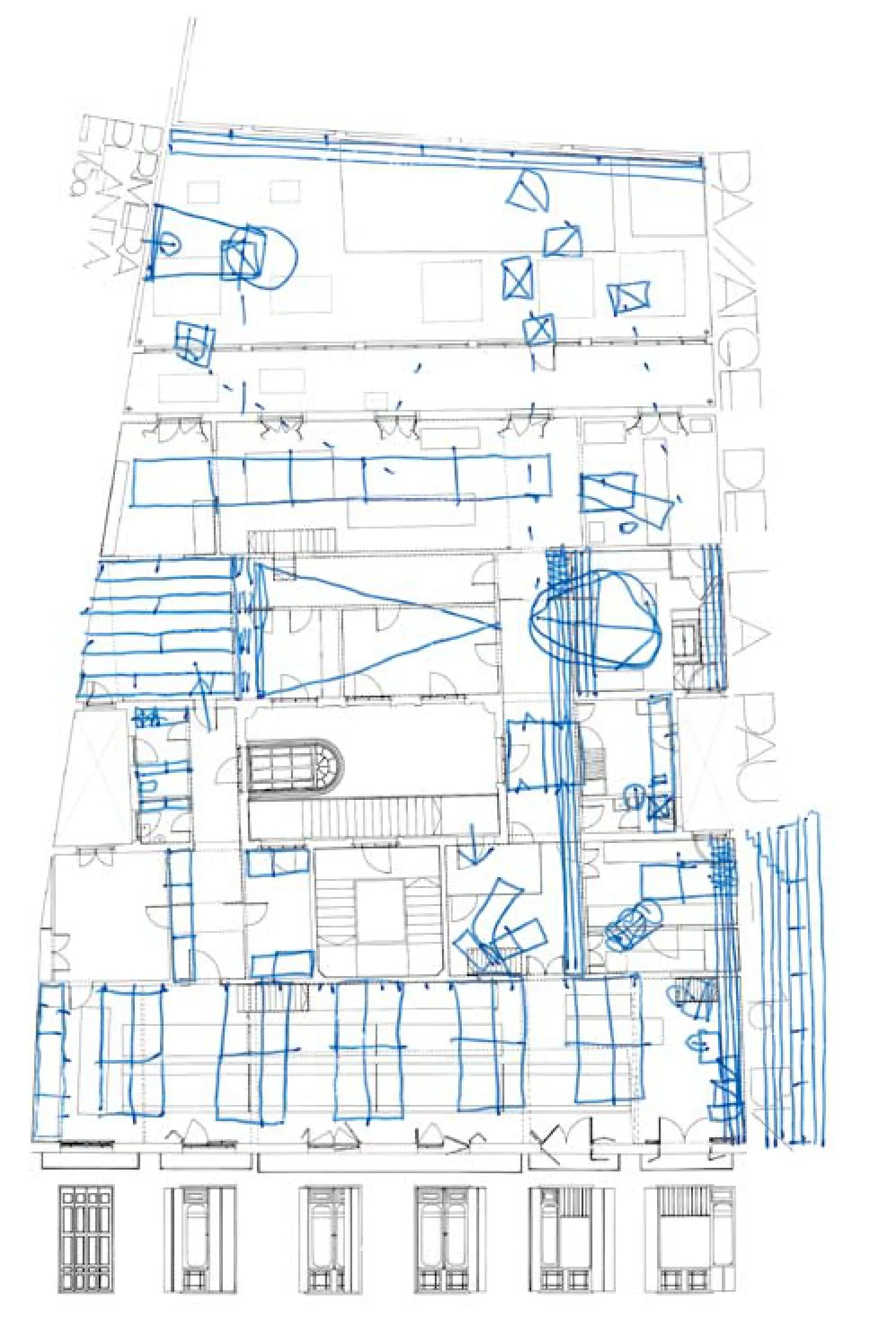

第二种方式在表现建筑价值观方面更为隐晦、微妙。这里有对可达性的温柔讽刺 (源计划建筑师事务所),有对游戏精神的悄声赞美(ADA研究中心现代建筑研究所),也有对材料工艺传统的依依不舍(米拉莱斯-塔格利亚布EMBT建筑师事务所)。

无论如何,从所有案例中都可看到,建筑师工作室是承载了其建筑师最多情感的作品之一,因而,它绝对不会是建筑师最容易的作品。如果说建筑师在其他作品中不可能享受到完全的自在的话,那么在这里,他(她)享受的绝不仅是自在之喜,也同样有自在之忧。

Obviously, the top-down approach is more explicit. In the offices published in this issue there are a number of exploration: the wholesale reinterpretation of oriental subject-object relationship (HE Jingtang, ZHANG Ming and YANG Ying); the implanting of culture into industrial/ commercial spaces (Bofill, SONG Zhaoqing); the abstract interaction between light, air and organisms (Selgascano, ZHANG Ke).

The bottom-up approach is more implicit. In this issue we see some mild satires of circulation (O-office), silent compliments of play (WANG Yun), and lingering feelings towards making and craft (Miralles Tagliabue EMBT).

No matter how different these work spaces are, we see one thing in common. The architect's work space is the project which he/she attaches him/ herself, therefore it carries the joy and the anxiety of the architect in very honest ways.

Design for Oneself: the Joy and the Anxiety of Freedom

ZHANG Li

米拉莱斯-塔格利亚布EMBT建筑师事务所平面草图,恩里克·米拉莱斯,1997/Plan sketch of Miralles Tagliabue EMBT, by Enric Miralles, 1997

清华大学建筑学院/《世界建筑》

2015-04-06