The Photographs in the Dark Museum House

Orhan Pamuk

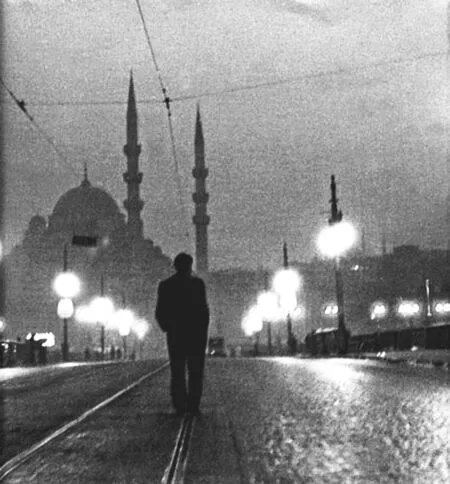

《伊斯坦布尔:一座城市的记忆》

土耳其著名作家奥尔罕·帕慕克(Orhan Pamuk,1952— )出生于一个富裕的西化的家庭,祖父因办工厂发家,死后将大笔家产留给两个儿子。然而作者的父亲和叔叔并不擅长经营,导致家道败落。高中时父母离异,作者随母亲一起生活。帕慕克不顾整个家庭的反对毅然走上创作的道路。七年后,他出版了第一部小说《塞夫得特州长和他的儿子们》,并获得《土耳其日报》小说首奖和奥尔罕·凯马尔小说奖。2006年因《伊斯坦布尔:一座城市的记忆》(Istanbul: Memories and the City)一书获诺贝尔文学奖,本文节选自该部作品。

帕慕克以其独特的个人视角及历史感讲述了他的家族史——从祖父的显赫到父辈的逐渐没落。三代人住在一栋五层的公寓楼里,每一家都有自己的佣人,亲戚们聚在一起时表面上热闹喜庆,暗地里却为了金钱和争家产钩心斗角、互相指责。尽管家道逐渐没落,祖母仍恪守往日上层社会的规矩和习俗,在她眼里,客厅就是一个家族的博物馆,主人在这里接待假想中的客人,因此在客厅里必须正襟危坐,不允许懒散怠慢。而客厅里的那一张张照片更是将往日生活的瞬间定格在一幅幅相框里,供后代们品味和遐想,这些正好给作者提供了丰富的写作素材,于是便有了下面的文字。

My mother, my father, my older brother, my grandmother, my uncles, and my aunts—we all lived on different floors of the same fivestory apartment house. Until the year before I was born,the different branches of the family had [as with so many large Ottoman(土耳其人的)families] lived together in a stone mansion; in 1951 they rented it out(出租)to a private elementary school and built on the empty lot(一块地)next door the modern structure I would know as home; on the façade(正面), in keeping with(与……一致)the custom of the time, they proudly put up a plaque(牌匾)that said PAMUK APT(帕穆克公寓). We lived on the fourth floor,but I had the run of(在……自由活动)the entire building from the time I was old enough to climb off my mother’s lap and can recall that on each floor there was at least one piano. When my last bachelor(单身)uncle put his newspaper down long enough to get married, and his new wife moved into the first-floor apartment, from which she was to spend the next half century gazing out the window,she brought her piano with her. No one ever played, on this one or any of the others; this may be why they made me feel so sad.

But it wasn’t just the unplayed piano; in each apartment porcelains(瓷器), teacups, silver sets(银器), sugar bowls,snuffboxes(鼻烟盒), crystal glasses, rosewater ewers(有玫瑰香水味的大口水壶), plates, and censers(香炉)that no one ever touched, although among them I sometimes found hiding places for miniature cars(模型车). There were the unused desks inlaid with mother-of-pearl(镶嵌着珍珠母), the turban(穆斯林头巾,狭边帽)shelves on which there were no turbans, and the Japanese and Art Nouveau(新艺术)screens behind which nothing was hidden. There, in the library, gathering dust behind the glass, were my doctor uncle’s medical books; in the 20 years since he’d emigrated(移居国外)to America, no human hand had touched them. To my childish mind, these rooms were furnished not for the living, but for the dead. [Every once in a while a coffee table or a carved chest(有雕刻的柜子)would disappear from one sitting room only to appear in another sitting room on another floor.]

If she thought we weren’t sitting properly on her silver-threaded chairs, our grandmother would bring us to attention.“Sit up straight!”Sitting rooms were not meant to be places where you could lounge(懒洋洋地坐着或躺着)comfortably; they were little museums designed to demonstrate to a hypothetical visitor(想象的客人)that the householders were westernized(西化的). A person who was not fasting(斋戒,禁食)during Ramadan1. Ramadan: 斋月,伊斯兰教历的九月,该月名字意为“禁月”,是穆斯林封斋的一个月,是真主安拉(Allah)将古兰经(Quran)下降给穆罕默德圣人的月份。would perhaps suffer fewer pangs of conscience(良心上的折磨)among these glass cupboards and dead pianos than he might if he were still sitting cross-legged in a room full of cushions and divans(长沙发椅). Although everyone knew it as freedom from the laws of Islam, no one was quite sure what else westernization was good for. So it was not just in the affluent(富裕的)homes of Istanbul(伊斯坦布尔,土耳其城市)that you saw sitting-room museums; over the next 50 years you could find these haphazard(偶然的)and gloomy(暗淡的)(but sometimes also poetic) displays of western influence in sitting rooms all over Turkey; only with the arrival of television in the 1970s did they go out of fashion. Once people had discovered how pleasurable it was to sit together to watch the evening news, their sitting rooms changed from little museums to little cinemas—although you still hear of old families who put their televisions in their central hallways(走廊,门厅), locking up their museum sitting rooms and opening them only for holidays or special guests.

Because the traffic(这里指在走廊和楼梯之间过往穿梭的家人和亲戚)between floors was incessant(不断的), as it had been in the Ottoman mansion, doors in our modern apartment building were usually left open. Once my brother had started school, my mother would let me go upstairs alone, or else we would walk up together to visit my paternal grandmother in her bed. The tulle(薄纱)curtains in her sitting room were closed, but it made little difference; the building next door was so close as to make the room very dark anyway, especially in the morning, so I’d sit on the large heavy carpets and invent a game to play on my own. Arranging the miniature cars that someone had brought me from Europe into an obsessively(强迫性地)neat line, I would admit them one by one into my garage. Then, pretending the carpets were seas and the chairs and tables islands, I would catapult(快速移动)myself from one to the other without ever touching water(much as Calvino’s Baron2. Italo Calvino: 伊塔洛·卡尔维诺(1923—1985),意大利新闻工作者、短篇小说家、作家,他奇特和充满想象的寓言作品使他成为20世纪最重要的意大利小说家之一。这里引用的是其作品《树上的公爵》一书中的公爵(Baron)。spent his life jumping from tree to tree without ever touching ground). When I was tired of this airborne(空中的)adventure or of riding the arms of the sofas like horses (a game that may have been inspired by memories of the horse-drawn carriages of Heybeliada3. Heybeliada: 王子群岛最大的两个岛之一,位于离伊斯坦布尔不远的马尔马拉海面上。),I had another game that I would continue to play as an adult whenever I got bored: I’d imagine that the place in which I was sitting [this bedroom, this sitting room, this classroom,this barracks(兵营), this hospital room, this government office] was really somewhere else; when I had exhausted the energy to daydream, I would take refuge(躲避)in the photographs that sat on every table, desk, and wall.

Never having seen them put to any other use, I assumed pianos were stands(架子)for exhibiting photographs.There was not a single surface in my grandmother’s sitting room that wasn’t covered with frames of all sizes. The most imposing(威风的,给人深刻印象的)were two enormous portraits that hung over never-used fireplace: One was a retouched(修补润色过的)photograph of my grandmother,the other of my grandfather, who died in 1934. From the way the pictures were positioned on the wall and the way my grandparents had been posed (turned slightly toward each other in the manner still favored by European kings and queens on stamps), anyone walking into this museum room to meet their haughty(高傲的)gaze would know at once that the story began with them.

They were both from a town near Manisa(马尼萨,土耳其一座城市)called Gӧrdes; their family was known as Pamuk (cotton) because of their pale(发白的)skins and white hair. My paternal grandmother was Circassian(切尔克斯人)[Circassian girls, famous for being tall and beautiful, were very popular in Ottoman harems(闺房)]. My grandmother’s father had immigrated to Anatolia during the Russian-Ottoman War (1877—78), settling first in Izmir (from time to time there was talk of an empty house there)and later in Istanbul,4. Russian-Ottoman War: 是指17—19世纪俄国与奥斯曼土耳其帝国之间的一系列战争,是欧洲历史上最长的战争系列,其结果是俄国扩大了疆土,土耳其逐渐衰落,1877—1878年为第10次俄土争夺势力范围进行的战争;Izmir: 伊兹密尔,是土耳其第三大城市。where my grandfather had studied civil engineering(土木工程). Having made a great deal of money during the early 1930s, when the new Turkish Republic was investing heavily in railroad building, he built a large factory that made everything from rope to a sort of twine(麻线,细绳)to dry tobacco; the factory was located on the banks of the Gӧksü(各克苏河), a stream that fed into the Bosphorus(博斯普鲁斯海峡). When he died in 1934 at the age of 52, he left a fortune so large that my father and my uncle never managed to find their way to the end of it, in spite of a long succession of failed business ventures.

Moving on to the library, we find large portraits(肖像,画像)of the new generation arranged in careful symmetry(对称)along the walls; from their pastel(粉蜡笔)coloring we can take them to be the work of the same photographer... My prolonged study of these photographs led me to appreciate the importance of preserving(保存)certain moments for posterity(子孙后代), and in time I also came to see what a powerful influence these famed scenes exerted(施以影响)over us as we went about our daily lives. To watch my uncle pose my brother a math problem(给我哥哥出一道数学题), and at the same time to see him in a picture taken 32 years earlier;to watch my father scanning the newspaper and trying,with a half smile, to catch the tail of a joke(抓住笑话的结尾)rippling across(席卷,波及)the crowded room,and at that very same moment to see a picture of him at five years old—my age—mother had framed and frozen these memories so we could weave them into the present.5. 母亲把这些瞬间记忆定格在相框里,以便我们把这些回忆编织进当下的生活。When, in tones ordinarily reserved(以平时只在……的时候才使用的声调)for discussing the founding of a nation,my grandmother spoke of my grandfather, who had died so young, and pointed at the frames on the tables and the walls, it seemed that she—like me—was pulled in two directions, wanting to get on with life but also longing to capture(捕捉)the moment of perfection, savoring(尽情享受)the ordinary but still honoring the ideal. But even as I pondered(沉思)these dilemmas(困境)— if you pluck(采摘)a special moment from life and frame it, are you defying(反抗)death, decay(衰退), and the passage of time(时光流逝)or are you submitting to(屈服于)it?—I grew very bored with them.

In time I would come to dread(惧怕)those long festive(节日的)lunches, those endless evening celebrations, those New Year’s feasts when the whole family would linger(消磨时光)after the meal to play lotto(一种对号码的牌戏,乐透); every year, I would swear it was the last time I’d go, but somehow I never managed to break the habit. When I was little, though, I loved these meals. As I watched the jokes travel around the crowded table, my uncles laughing [under the influence of vodka(伏特加酒)or rakı (拉克酒)] and my grandmother smiling (under the influence of the tiny glass of beer she allowed herself), I could not help but notice how much more fun life was outside the picture frame. I felt the security of belonging to a large and happy family and could bask in the illusion(沐浴在幻想中)that we were put on earth to take pleasure in it. Not that I was unaware that these relatives of mine who could laugh, dine, and joke together on holidays were also merciless and unforgiving in quarrels over money and property. By ourselves, in the privacy of our own apartment, my mother was always complaining to my brother and me about the cruelties of“your aunt”, “your uncle”, “your grandmother”. In the event of a disagreement over who owned what, or how to divide the shares of the rope factory, or who would live on which floor of the apartment house, the only certainty was that there would never be a resolution(解决方案). These rifts(裂痕)may have faded(逐渐消失)for holiday meals,but from an early age I knew that behind the gaiety(喜庆的气氛)there was a mounting pile of unsettled scores(堆积如山且悬而未决的争端)and a sea of recriminations(大量的互相指责).

Each branch of our large family had its own maid,and each maid considered it her duty to take sides(站在谁的一边)in the wars. Esma Hanim, who worked for my mother, would pay a visit to İkal, who worked for my aunt. Later, at breakfast, my mother would say, “Did you hear what Aydin’s saying?”

If I was too young to understand the underlying(潜在的)cause of these disputes—that my family, still living as it had done in the days of the Ottoman mansion, was slowly falling apart—I could not fail to notice my father’s bankruptcies(破产)and his ever-morefrequent absences... Apart from the occasional show of temper, my father found little to complain about;he took a childish delight in his good looks, his brains, and the good fortune he never tried to hide. Inside, he was always whistling, inspecting his reflection in the mirror, rubbing a wedge of lemon(一片柠檬)like brilliantine(润发油)on his hair. He loved jokes, word games, surprises, reciting poetry,showing off his cleverness, taking planes to faraway places.He was never a father to scold(责骂), forbid, or punish.When he took us out, we would wander all over the city,making friends wherever we went; it was during these excursions(游览)that I came to think of the world as a place made for taking pleasure.

If evil ever encroached(侵蚀), if boredom loomed(若隐若现), my father’s response was to turn his back on it and remain silent. My mother, who set the rules, was the one to raise her eyebrows and instruct us in life’s darker side. If she was less fun to be with, I was still very dependent on her love and attention, for she gave us far more time than did our father, who seized every opportunity to escape from the apartment. My harshest(最严酷的)lesson in life was to learn I was in competition with my brother for my mother’s affections.

作者奥尔罕·帕慕克

Although my brother’s adventure comics(漫画)may have inspired this dream, so too did my thoughts about God. God had chosen not to bind us to the city’s fate, I thought, simply because we were rich. But as my father and my uncle stumbled(绊倒)from one bankruptcy(破产)to the next, as our fortune dwindled(减少)and our family disintegrated(瓦解)and the quarrels over money grew more intense, every visit to my grandmother’s apartment became a sorrow and took me a step closer to a realization: It was a long time coming, arriving by a circuitous(迂回的)route, but the cloud of gloom(忧郁)and loss spread over Istanbul by the fall of the Ottoman Empire had finally claimed(夺走)my family too.