植物挥发性有机物合成研究进展

李芳芳陶书田张虎平,2

(1.南京农业大学园艺学院,南京 210095;2.石河子大学农学院,石河子 832003)

植物挥发性有机物合成研究进展

李芳芳1陶书田1张虎平1,2

(1.南京农业大学园艺学院,南京 210095;2.石河子大学农学院,石河子 832003)

植物挥发性有机物与人类生产和生活密切相关。在农业研究方面,植物挥发性有机物具有吸引传粉昆虫,抵御生物和非生物胁迫,介导作物之间信息交流,赋予果实特征风味等重要作用。综述了萜类化合物、苯/苯丙烷类化合物、脂肪酸衍生物和氨基酸衍生物等4类挥发性有机物的合成研究现状,并提出了今后应开展的工作与方法,旨在为进一步开展本领域研究提供有用信息。

挥发性有机物;合成;代谢;植物

植物挥发性有机物(volatile organic compounds,VOCs),也称为挥发物(Volatiles),是植物次生代谢产物的一部分,可由植物的花、果、根、叶等不同器官产生。迄今为止,已从被子植物和裸子植物的90种不同科属中鉴定出1 700多种挥发性有机物[1]。研究表明,植物挥发性有机物与人类生产和生活密切相关,它们在吸引传粉昆虫[2],保护作物免受生物和非生物胁迫[3,4],介导植物-植物之间的通讯[5],赋予特定种类和品种果实特征风味[6]等方面具有十分重要的作用。此外,有些植物挥发性有机物可引起人体生理和心理变化,具有对人体健康有利的成分[7]。近年来,对植物挥发性有机物的研究倍受关注。根据它们的生物合成来源,所有的植物挥发性有机物可分为4类,包括萜类化合物、苯/苯丙烷类化合物、脂肪酸衍生物和氨基酸衍生物(少数特殊的化合物除外)[8]。本文针对这4类有机物合成方面的一些研究进展进行综述,以期为相关研究提供参考。

1 萜类化合物的生物合成

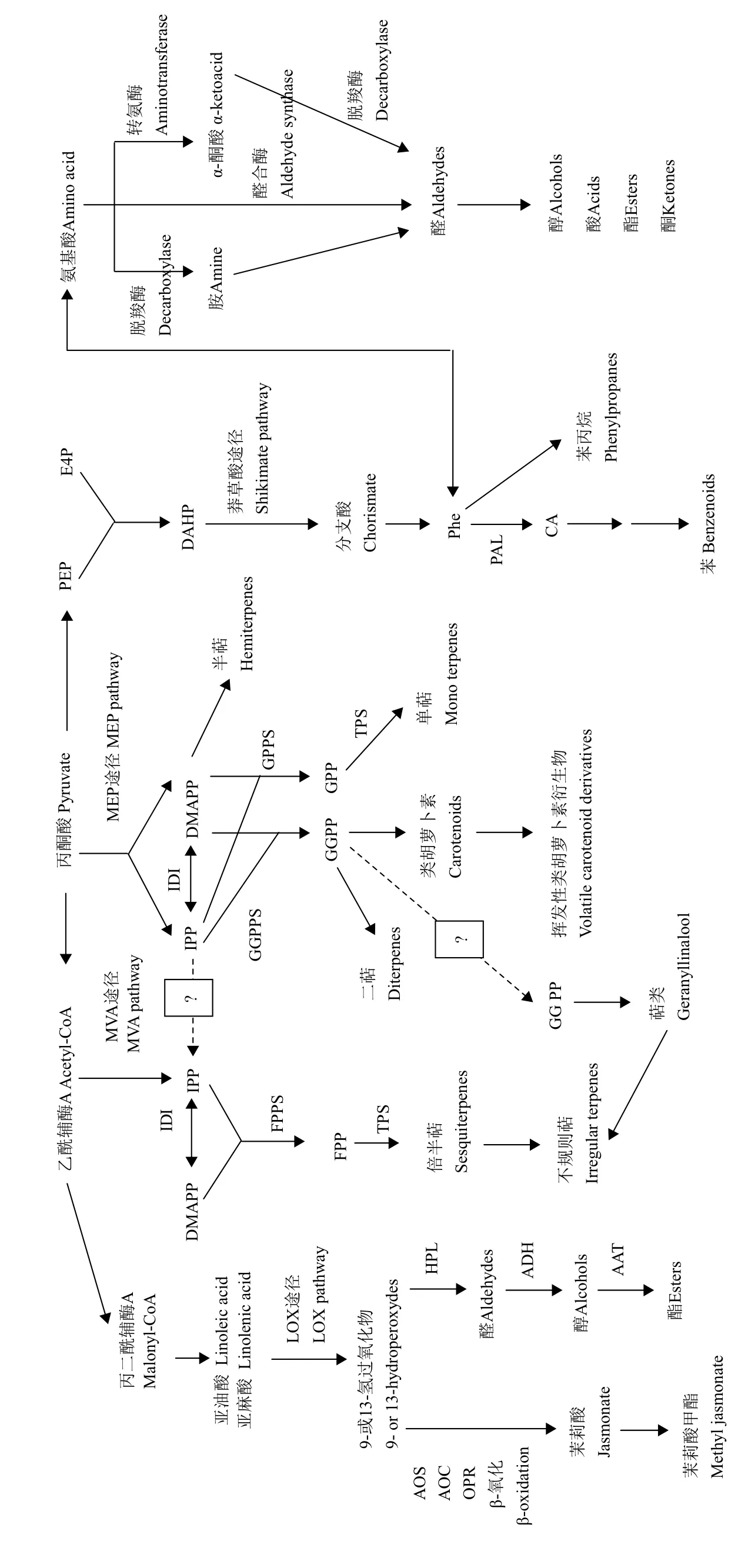

萜类化合物是挥发性成分中数量最大、种类最丰富的一类次生代谢物,它们来自两个五碳前体化合物——异戊烯焦磷酸(isopentenyl pyrophosphate,IPP)及其烯丙基的异构体:二甲烯丙基焦磷酸(dimethylallyl-pp,DMAPP)[9]。在植物中,负责这些五碳异戊二烯结构单元形成的途径为甲羟戊酸(mevalonate,MVA)途径和2-C-甲基-D-赤藓醇-4-磷酸(2-C-methyz-D-erythritol-4-Phosphcite,MEP)途径(图1)。MVA途径产生了挥发性倍半萜(C15),而MEP途径提供了挥发性半萜(C5)、单萜(C10)和双萜(C20)的前体。根据试验证据及亚细胞定位的预测,MEP途径有一整套相应的酶仅存在于质体中,因此MEP途径被认为是一个质体途径[10]。相比之下,MVA途径的亚细胞定位并不明确,但新的研究表明,MVA通路分布于细胞质、内质网和过氧化物酶体之间[11]。

MVA途径包含6个酶促反应,最初由3分子的乙酰-CoA逐步缩合为3-羟基-3-甲基戊二酰基-CoA,接着被还原成MVA,然后经过磷酸化和脱羧/消去反应得以形成最终产物IPP(图1)[12]。到目前为止,仍然不清楚乙酰-CoA的亚细胞区是否用于萜类物质的合成,因为乙酰-CoA不能轻易横跨细胞膜,且亚细胞区存在于叶绿体、过氧化体、线粒体、细胞质和细胞核内[13]。拟南芥基因组中包含两个编码乙酰-CoA转移酶(acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase,AACT)的基因,其中AACT2催化MVA途径的第一个步骤[14],根据蛋白质组分析,它被定位在过氧化体中[8]。

MEP途径涉及7个酶促步骤,最初由D-甘油醛-3-磷酸(GAP)和丙酮酸(Pyr)缩合产生1-脱氧-D-木酮糖-5-磷酸,然后进行异构化/还原形成该途径的特征性中间体MEP。MEP转换为IPP和DMAPP需要连续的5个步骤。MEP途径依赖初级代谢提供Pyr和GAP,后者来源于糖酵解途径和磷酸戊糖途径(PPP)。至今,Pyr在叶绿体内的来源尚不完全清楚,因为起关键作用的糖酵解酶、磷酸甘油酸变位酶和烯醇化酶在质体内具有低的活性[15-17],并且可能无法维持高Pyr对异戊二烯生物合成的需求。

IPP和DMAPP是短链异戊烯的底物,由此可产生异戊烯二磷酸前体、香叶基焦磷酸(GPP)、法尼基焦磷酸(FPP)和香叶基香叶基焦磷酸(GGPP,又名牻牛儿基牻牛儿基焦磷酸)(图1)[18]。MVA途径只产生IPP,而MEP途径可按6∶1的合成比例产生IPP和DMAPP。因此,这两个途径都依赖于异戊烯基焦磷酸异构酶(IDI),其可逆地将IPP转换成DMAPP,并控制它们之间的平衡[19]。最近,IDI基因分别在长春花(Catharantbus roseus)和拟南芥(Arabidopsis thaliana)基因组中被鉴定。在这两种植物中,“长”蛋白质被定位到线粒体和/或叶绿体中,而缺乏靶信号的“短”蛋白质则位于过氧化体[20],这突出显示了不同亚细胞器参与了植物类异戊二烯的生物合成。

IPP、DMAPP和短链异戊烯二磷酸(GPP和FPP)作为连接产物促进了MVA途径和MEP途径之间的“代谢交流”[21]。MEP途径具有比MVA途径更高的碳通量,以支持萜类化合物在细胞质中的生物合成[22]。这些途径使得萜类化合物的生物合成具有物种和/或器官特异性。

例如,在金鱼草(Antirrhinum majus)的花中,MEP途径为细胞质倍半萜的形成提供前体[23],而在胡萝卜(Daucus carota)的叶和根中倍半萜则同时来自MEP和MVA途径[24]。挥发性萜类化合物在植物中的多样性是通过萜类合成酶(TPSs)的作用产生的,它们中的很多有将单一异戊二烯焦磷酸底物合成多个产物的独特能力[25]。事实上,在拟南芥中的2个倍半萜合酶TPS21和TPS11能合成花卉挥发性物质中发现的所有20种倍半萜[26]。此外,许多TPSs能接受多个底物来扩大萜类化合物的多样性[4,27]。近期的研究表明,番茄(Solanum lycopersicum)单萜和倍半萜合成酶可以使顺式结构的异戊烯二磷酸,如橙花二磷酸(NDP)和Z,Z-FPP形成新的产物,而不是通常的GPP和E,E-FPP[28]。然而,它是否是TPSs的一般属性仍有待确定。

迄今为止,植物中的TPS基因家族成员多于100个,其中约1/3分离于花和果实。基于序列相似性、功能特性和基因结构,该基因家族分为7个亚家族,包括TPS-a-TPS-g。有趣的是,与酶的功能相比,来自相关植物种类的TPSs更倾向于聚在一块[29]。最近,Eduardo等[30]用高密度的SNP定位了两个负责桃果实萜类合成的基因(ppa002670m和ppa003380m),分别负责芳樟醇和松油醛的合成,这一成果为果实中萜类合成基因的分类和功能验证奠定了基础。

图1 植物挥发性有机物(VOCs)生物合成途径[10]

除了TPSs直接形成大部分的挥发性萜类化合物外,通过羟基化、脱氢化、酰基化或其他反应修饰TPSs产物的酶增加了萜类化合物的挥发性,改变了嗅觉特性,进一步增加了挥发性萜类化合物的多样性。植物也用C8到C18的碳骨架产生不规则的挥发性萜类化合物,这源于类胡萝卜素通过3个步骤的修饰,包括最初的双加氧酶裂解,其次是酶促转化,然后通过酸催化转化为挥发性化合物[31]。在某些情况下,如拟南芥、番茄、矮牵牛(Petunia hybrida)和甜瓜(Cucumis melo),双加氧酶裂解步骤本身可以产生一些挥发性产物,如类胡萝卜素中的α-和β-紫罗兰酮、香叶基丙酮和假紫罗兰酮等[32,33]。

2 苯/苯丙烷类化合物的生物合成

植物挥发性有机物的第二大类包括苯及苯丙烷类化合物[1],其起源于芳香族氨基酸苯丙氨酸(Phe)(图1)。莽草酸途径的7个酶促反应和Phe-Tyr合成途径3个反应连接中心碳代谢形成苯丙氨酸[34]。莽草酸途经的直接前体磷酸烯醇式丙酮酸(PEP)和4-磷酸赤藓糖(E4P)分别来自糖酵解和磷酸戊糖途径。MEP途径的前体同样由此提供。因此,MEP途径必须与莽草酸/苯丙烷途径竞争碳的分配,其中莽草酸途径的第一个酶——3-脱氧-D-阿拉伯庚酮糖酸-7-磷酸(DAHP)合成酶在控制碳流方向方面起到关键作用[35]。然而,植物中这个途径的分子机制仍然未知[34]。

苯丙氨酸生物合成发生在质体中[34],其进一步转化为挥发性化合物则发生在这种细胞器之外。大多数苯/苯丙烷类化合物生物合成的第一个关键步骤是L-苯丙氨酸解氨酶(PAL)催化苯丙氨酸直接脱氨产生反式肉桂酸(CA)。肉桂酸中的苯环型化合物(C6-C1)形成需要丙基侧链缩短2个碳原子,并且已被证明能够通过β-氧化途径或非β-氧化途径或这些途径的组合进行,类似于脂肪酸和某些支链氨基酸的分解代谢过程。该途径开始于CA活化成其CoA硫酯,它经历水化、氧化和β-酮硫酯的裂解,从而形成苯甲酰基-CoA[36]。随着β-氧化途径定位于过氧化物酶体,提出了关于苯甲酰基-CoA输出到细胞质合成苯甲酸苄酯和苯乙基苯甲酸甲酯的问题。

非β-氧化途径通过作为关键中间体的苯甲醛进行,随后被氧化为苯甲酸。而依赖于NAD+的苯甲醛脱氢酶将苯甲醛转化为苯甲酸已被证实[37],然而形成苯甲醛的生物化学步骤仍然不清楚。此前10年,人们在参与苯环型挥发物形成最后步骤的酶和基因发现方面取得了显著进展。研究发现酰基转移酶的BAHD大家族和甲基转移酶的SABATH家族对挥发性苯环型化合物最后几个生物合成步骤的贡献极大[38,39]。

挥发性苯丙烯类(C6-C3),如丁香酚、异丁香酚、甲基丁香酚、异甲基丁香酚、味醇和甲基味醇,其生物合成的最初几个步骤与木质素的生物化学合成途径相同,直到形成苯基丙烯醇阶段,然后需要两个酶促反应,以消除在C9位上的氧[40,41]。松柏醇在通过丁香酚合酶或异丁香酚合酶还原为丁香酚和异丁香酚之前先由松柏醇乙酰基转移酶将其合成松柏酯[41,42]。类似于松柏酯在形成丁香酚和异丁香酚中的作用,香豆醋酸是味醇生物合成的前体[43]。通常,丁香酚、异丁香酚及味醇经过进一步的甲基化,需要O-甲基化酶形成下游产物甲基丁香酚、异甲基丁香酚和甲基味醇[44]。

与苯和苯丙烯类化合物相比,挥发性苯丙烷类(C6-C2)化合物的生物合成,如苯乙醛和2-苯乙醇,无需通过CA途径同PAL竞争苯丙氨酸[45,46]。在矮牵牛和玫瑰(Rosa rugosa)的花瓣中,苯乙醛直接由苯乙醛合酶催化苯丙氨酸经一个特殊的脱羧-胺氧化反应形成[45,47],而在番茄中,该过程需要经过两个独立的步骤,即苯丙氨酸先在芳香氨基酸脱羧酶的作用下转化为苯乙胺,并在一个假设的胺氧化酶、脱氢酶,或转氨酶作用下形成苯乙醛[48]。最近,在甜瓜果实中发现第三个酶促反应,在其中苯丙氨酸首先转胺化形成相应的α-酮酸或苯丙酮酸,接着进行脱羧反应形成苯乙醛[49](图1)。

3 挥发性脂肪酸衍生物的生物合成

另一类植物挥发性有机物由脂肪酸衍生物组成,如1-己醛、顺-3-己烯醇、壬醛和茉莉酸甲酯等,它们由C18的不饱和脂肪酸、亚油酸或亚麻酸产生(图1)。这些脂肪酸的生物合成依赖于一个乙酰-CoA的质体池,它从糖酵解的终产物Pyr中产生。在这个生化过程中至少有4种酶参与,即脂氧合酶(lipoxygenase,LOX)、氢过氧化物裂解酶(hydroperoxidelyase,HPL)、乙醇脱氢酶(alcohol dehydrogenase,ADH)和乙酰基转移酶(alcohol acetyltransferase,AAT)。进入“LOX途径”后,不饱和脂肪酸经过高专一性氧合,形成9-氢过氧化物及13-氢过氧化物中间体(图1)[50],然后通过LOX途径的两个分支进一步代谢产生挥发性化合物。目前已从番茄、猕猴桃、苹果和橄榄等果实中鉴别出参与香气形成的LOX家族成员,根据脂肪酸氧化的位置特性可分为9-LOX和13-LOX两种不同的类型,分别在碳水化合物的9位碳或13位碳上氧化分别形成9S和13S-氢过氧化物衍生物[51,52]。丙二烯氧合酶(allene axide synthase,AOS)分支只用13-氢过氧化物中间体形成茉莉酸(jasmonate,JA),而JA通过茉莉酸羧基甲基转移酶转化成茉莉酸甲酯(methyl jasmonate,MeJA)[53]。与此相反,氢过氧化物裂解酶的分支将这两种类型的氢过氧化脂肪酸衍生物转换形成C6和C9的醛,这些醛类往往在醇脱氢酶的作用下被还原为醇,并进一步转化为相应的酯(图1)。这些饱和的与不饱和的C6/C9醛和醇通常被称为绿叶挥发物(green leaf volatiles,GLVs),常在植物的绿色器官合成以响应损伤,但同时也赋予了水果和蔬菜特有的“芳草味”[39]。最近,南京农业大学梨课题组以来自不同栽培种的部分中国梨品种和33个有代表性的秋子梨品种为材料,通过分析果实中挥发性芳香物质的组成变化及其与代谢底物间的相关性,发现梨果实中挥发性芳香物代谢的主要底物是脂肪酸;其次是氨基酸[54]。更为重要的是,在对梨的基因组研究中发现,与梨脂肪酸代谢途径相关LOX和ADH基因数量更多,在果实发育过程中1/3的LOX同源基因高度表达,并且在果实发育中期表达量达到顶峰,与此同时,在果实发育阶段ADH的表达量随着乙醇的形成而增加[55]。进一步说明脂肪酸代谢途径对于梨果实香气的形成可能是非常重要的。这些结果对以提高香气作为主要目标的梨果实生理代谢研究提供了非常有价值的参考。

4 氨基酸支链衍生物的生物合成

氨基酸途径是芳香族香气物质的合成途径(图1)。目前发现许多挥发性化合物,特别是那些在花香和水果香味中高丰度的化合物,衍生于氨基酸如丝氨酸(Ser)、丙氨酸(Ala)、缬氨酸(Val)、亮氨酸(Leu)、异亮氨酸(Ile)和甲硫氨酸(Met),或在它们生物合成中含氮和硫的中间体[1]。草莓、番茄、葡萄等不同种类的果实中存在大量来源于亮氨酸的化合物3-甲基正丁醛、3-甲基丁醇、3-甲基正丁酸和来源于苯丙氨酸的苯乙醛、苯乙醇。另外,来源于氨基酸的醇、酸形成的化合物酯对果实香气也有重要影响,如香蕉中的乙酸-3-甲基-2-丁酯和3-甲基-丁酸丁酯[54]。

氨基酸的代谢途径中存在两步共同的酶反应:转氨基作用和脱羧基作用,两种反应的关键酶分别为转氨酶和丙酮酸脱氢酶。现有研究结果表明,植物挥发物中氨基酸衍生物的生物合成过程与细菌或酵母中的合成方式相似[56]。在微生物中,氨基酸经转氨酶催化脱氨或转氨,形成相应的α-酮酸(图1)[49]。这些α-酮酸进一步进行脱羧反应,接着经过缩合、氧化或酯化,形成醛、酸、醇和酯(图1)。因此,转氨酶和脱羧酶是氨基酸形成甲基支链香气物质的两个关键酶。氨基酸也可以作酰基-CoA的前体,用在由醇酰基转移酶(AAT)催化的醇酯化反应中,合成芳香族的醇、酸和酯类物质[57]。尽管支链氨基酸、芳香族氨基酸和甲硫氨酸降解形成的醛和醇构成了植物的一大类香气成分,但很少有人研究其代谢途径,尤其是来源于支链氨基酸的支链挥发性物质。

5 问题与展望

尽管人们已经知道植物挥发性有机物的合成是从几个初级代谢产物开始的,单个酶催化不同底物合成多种产物是挥发性有机物合成过程的共同特点。但是,由于挥发性有机物代谢的复杂性和种属之间的特异性,目前对植物挥发性有机物合成的认识仍然十分有限,还有许多问题需要解决。(1)大多数挥发性有机物的研究主要是以花和叶等器官为主,对果实特别是如草莓、番茄、甜瓜、苹果及梨等肉质果实内挥发性有机物合成途径及其调控了解不多。今后应当加强挥发性代谢途径中相关基因的克隆与功能分析,搞清楚挥发性代谢成分代谢途径及其代谢产物的来龙去脉,确定挥发性代谢成分合成的细胞分区、定位和转运,以及各条代谢途径之间的相互关系和基因调控网络等。(2)在大多数情况下,基因被诱导表达是与一些重要挥发性化合物的产生相一致的,尽管许多挥发性有机物合成相关的结构基因已经得到克隆,但是合成相关的转录调控因子很少报道,特别是协调不同挥发性化合物形成并在多种代谢途径上游发挥作用的主要调控因子仍有待研究。而且,转录调控在控制植物挥发性有机物生物合成过程中不是唯一参与的机制,目前对于挥发性有机物形成的转录后调控仍不清楚。(3)任何挥发性有机物生物合成的速率不仅受限于负责最后步骤的酶的活性,也受限于可用的底物。因此,建立底物与挥发性有机物的直接关系以了解底物对挥发性有机物形成的调控作用是进行植物挥发性有机物合成机理研究的有效手段之一。

总之,随着不同“组学”以及稳定同位素技术、现代色谱技术、核磁共振等综合分析手段的应用,必将有利于推动植物挥发性有机物合成的研究,相信从整体水平解决上述问题不会困难。

[1]Knudsen JT, Eriksson R, Gershenzon J, et al. Diversity and distribution of floral scent[J]. Botanical Review, 2006, 72:1-120.

[2]Raguso RA. Wake up and smell the roses:the ecology and evolution of floral scent[J]. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 2008, 39:549-569.

[3]Hiltpold I, Turlings TCJ. Manipulation of chemically mediated interactions in agricultural soils to enhance the control of crop pests and to improve crop yield[J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 2012,38:641-650.

[4]Huang M, Sanchez-moreiras AM, Abel C, et al. The major volatile organic compound emitted from Arabidopsis thaliana flowers, the sesquiterpene(E)-b-caryophyllene, is a defense against a bacterial pathogen[J]. New Phytologist, 2012, 193:997-1008.

[5]Heil M, Karban R. Explaining evolution of plant communication by airborne signals[J]. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2010, 25(3):137-144.

[6]Husain Q. Handbook of fruit and vegetable flavours[M]. New Jersey:John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2010.

[7]宋秀华, 李传荣, 许景伟, 王超. 元宝枫叶片挥发物成分及其季节差异[J]. 园艺学报, 2014, 41(5):915-924.

[8]Dudareva N, Klempien A, Muhlemann JK, et al. Biosynthesis,function and metabolic engineering of plant volatile organic compounds[J]. New Phytologist, 2013, 198(1):16-32.

[9]Mc Garvey DJ, Croteau R. Terpenoid metabolism[J]. Plant Cell,1995, 7:1015-1026.

[10]Hsieh MH, Chang CY, Hsu SJ, et al. Chloroplast localization of methylerythritol 4-phosphate pathway enzymes and regulation of mitochondrial genes in IspD and IspE albino mutants in Arabidopsis[J]. Plant Molecular Biology, 2008, 66:663-673.

[11]Pulido P, Perello C, Rodriguez-concepcion M. New insights into plant isoprenoid metabolism[J]. Molecular Plant, 2012, 5:964-967.

[12]Lange BM, Rujan T, Martin W, et al. Isoprenoid biosynthesis:the evolution of two ancient and distinct pathways across genomes[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,USA, 2000, 97:13172-13177.

[13]Oliver DJ, Nikolau BJ, Wurtele ES. Acetyl-CoA life at the metabolic nexus[J]. Plant Science, 2009, 176:597-601.

[14]Ahumada I, Cairo A, Hemmerlin A, et al. Characterisation of the gene family encoding acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase in Arabidopsis[J]. Functional Plant Biology, 2008, 35:1100-1111.

[15]Andriotis VM, Kruger NJ, Pike MJ, et al. Plastidial glycolysis in developing Arabidopsis embryos[J]. New Phytologist, 2010,185:649-662.

[16]Joyard J, Ferro M, Masselon C, et al. Chloroplast proteomics highlights the subcellular compartmentation of lipid metabolism[J]. Progress in Lipid Research, 2010, 49:128-158.

[17]Bayer RG, Stael S, Csaszar E, et al. Mining the soluble chloroplast proteome by affinity chromatography[J]. Proteomics, 2011, 11:1287-1299.

[18]Wise ML, Croteau R. Monoterpene biosynthesis[M]//Cane DD, ed. Comprehensive natural products chemistry:isoprenoids including carotenoids and steroids. Amsterdam, the Netherlands:Elsevier, 1999:97-153.

[19]Nakamura A, Shimada H, Masuda T, et al. Two distinct isopentenyl diphosphate isomerases in cytosol and plastid are differentially induced by environmental stresses in tobacco[J]. FEBS Letters,2001, 506:61-64.

[20]Guirimand G, Guihur A, Phillips MA, et al. A single gene encodesisopentenyl diphosphate isomerase isoforms targeted to plastids,mitochondria and peroxisomes in Catharanthus roseus[J]. Plant Molecular Biology, 2012, 79:443-459.

[21]Hemmerlin A, Hoeffler JF, Meyer O, et al. Cross-talk between the cytosolic mevalonate and the plastidial methylerythritol phosphate pathways in tobacco bright yellow-2 cells[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2003, 278:26666-26676.

[22]Laule O, Furholz A, Chang HS, et al. Crosstalk between cytosolic and plastidial pathways of isoprenoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,USA, 2003, 100:6866-6871.

[23]Dudareva N, Andersson S, Orlova I, et al. The nonmevalonate pathway supports both monoterpene and sesquiterpene formation in snapdragon flowers[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 2005, 102:933-938.

[24]Hampel D, Mosandl A, Wüst M. Biosynthesis of mono- and sesquiterpenes in carrot roots and leaves(Daucus carota L.):metabolic cross talk of cytosolic mevalonate and plastidial methylerythritol phosphate pathways[J]. Phytochemistry, 2005,66:305-311.

[25]Degenhardt J, Köllner TG, Gershenzon J. Monoterpene and sesquiterpene synthases and the origin of terpene skeletal diversity in plants[J]. Phytochemistry, 2009, 70:1621-1637.

[26] Tholl D, Chen F, Petri J, et al. Two sesquiterpene synthases are responsible for the complex mixture of sesquiterpenes emitted from Arabidopsis flowers[J]. Plant Journal, 2005, 42:757-771.

[27] Gutensohn M, Nagegowda DA, Dudareva N. Involvement of compartmentalization in monoterpene and sesquiterpene biosynthesis in plants[M]//Bach TJ, Rohmer M, eds. Isoprenoid synthesis in plants and microorganisms. New York, NY, USA:Springer, 2013:155-169.

[28] Sallaud C, Rontein D, Onillon S, et al. A novel pathway for sesquiterpene biosynthesis from Z, Z-farnesyl pyrophosphate in the wild tomato Solanum habrochaites[J]. Plant Cell, 2009, 21:301-317.

[29] Bohlmann J, Meyer-gauen G, Croteau R. Plant terpenoid synthases:molecular biology and phylogenetic analysis[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 1998, 95:4126-4133.

[30]Eduardo I, Chietera G, Pirona R, et al. Genetic dissection of aroma volatile compounds from the essential oil of peach fruit:QTL analysis and identification of candidate genes using dense SNP maps[J]. Tree Genetics & Genomes, 2013, 1:189-204.

[31] Winterhalter P, Rouseff R. Carotenoid-derived aroma compounds:an introduction[M]//Winterhalter P, Rouseff R, eds. Carotenoidderived aroma compounds[J]. Washington, DC, USA:American Chemical Society, 2001:1-17.

[32]Simkin AJ, Schwartz SH, Auldridge M, et al. The tomato carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 1 genes contribute to the formation of the flavor volatiles b-ionone, pseudoionone, and geranylacetone[J]. Plant Journal, 2004, 40:882-892.

[33] Ibdah M, Azulay Y, Portnoy V, et al. Functional characterization of CmCCD1, a carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase from melon[J]. Phytochemistry, 2006, 67:1579-1589.

[34]Maeda H, Dudareva N. The shikimate pathway and aromatic amino acid biosynthesis in plants[J]. Annual Review of Plant Biology,2012, 63:73-105.

[35]Tzin V, Malitsky S, Ben Zvimm, et al. Expression of a bacterial feedback-insensitive 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate7-phosphate synthase of the shikimate pathway in arabidopsis elucidates potential metabolic bottlenecks between primary and secondary metabolism[J]. New Phytologist, 2012, 194:430-439.

[36]Van Moerkercke A, Schauvinhold I, Pichersky E, et al. A plant thiolase involved in benzoic acid biosynthesis and volatile benzenoid production[J]. Plant Journal, 2009, 60:292-302.

[37]Long MC, Nagegowda DA, Kaminaga Y, et al. Involvement of snapdragon benzaldehyde dehydrogenase in benzoic acid biosynthesis[J]. Plant Journal, 2009, 59:256-265.

[38]D'auria JC. Acyltransferases in plants:a good time to be BAHD[J]. Current Opinion In Plant Biology, 2006, 9:331-340.

[39]D'auria JC, Pichersky E, Schaub A, et al. Characterization of a BAHD acyltransferase responsible for producing the green leaf volatile(Z)-3-hexen-1-ylacetate in Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Plant Journal, 2007, 49:194-207.

[40]Koeduka T, Fridman E, Gang DR, et al. Eugenol and isoeugenol,characteristic aromatic constituents of spices, are biosynthesized via reduction of a coniferyl alcohol ester[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 2006, 103:10128-10133.

[41]Dexter R, Qualley A, Kish CM, et al. Characterization of a petunia acetyltransferase involved in the biosynthesis of the floral volatileisoeugenol[J]. Plant Journal, 2007, 49:265-275.

[42]Koeduka T, Louie GV, Orlova I, et al. The multiple phenylpropene synthases in both Clarkia breweri and Petunia hybrida represent two distinct protein lineages[J]. Plant Journal, 2008, 54:362-374.

[43]Vassao DG, Gang DR, Koeduka T, et al. Chavicol formation in sweet basil(Ocimum basilicum):cleavage of an esterified C9 hydroxyl group with NAD(P)H-dependent reduction[J]. Organic and Biomolecular Chemistry, 2007, 4:2733-2744.

[44]Gang DR, Lavid N, Zubieta C, et al. Characterization of phenylpropene O-methyltransferases from sweet basil:facile change of substrate specificity and convergent evolution within a plant O-methyltransferase family[J]. Plant Cell, 2002, 14:505-519.

[45]Kaminaga Y, Schnepp J, Peel G, et al. Plant phenylacetaldehyde synthase is a bifunctional homotetrameric enzyme that catalyzes phenylalanine decarboxy lationan doxidation[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2006, 281:23357-23366.

[46]Tieman DM, Loucas HM, Kim JY, et al. Tomato phenylacetaldehyde reductases catalyze the last step in the synthesis of the aroma volatile 2-phenylethanol[J]. Phytochemistry, 2007, 68:2660-2669.

[47]Farhi M, Lavie O, Masci T, et al. Identification of rose phenylacetaldehyde synthase by functional complementation in yeast[J]. Plant Molecular Biology, 2010, 72:235-245.

[48]Tieman DM, Taylor MG, Schauer N, et al. Tomato aromatic amino acid decarboxylases participate in synthesis of the flavor volatiles 2-phenylethanol and 2-phenylacetaldehyde[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 2006, 103:8287-8292.

[49]Gonda I, Bar E, Portnoy V, et al. Branched-chain and aromatic amino acid catabolism into aroma volatiles in Cucumis melo L. fruit[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2010, 61:1111-1123.

[50]Feussner I, Wasternack C. The lipoxygenase pathway[J]. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 2002, 53:275-297.

[51]Chen G, Hackett R, Walker D, et al. Identification of a specific isoform of tomato lipoxygenase(TomloxC)involved in the generation of fatty acid-derived flavor compounds[J]. Plant Physiology, 2004, 136(1):2641-2651.

[52]Zhang B, Chen K, Bowen J, et al. Differential expression within the LOX gene family in ripening kiwifruit[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2006, 57(14):3825-3836.

[53]Song M, Kim D, Lee S. Isolation and characterization of a jasmonic acid carboxyl methyltransferase gene from hot pepper(Capsicum annuum L. )[J]. Journal of Plant Biology, 2005, 48:292-297.

[54]秦改花. 梨果实挥发性芳香物质的分析和生物合成研究[D].南京:南京农业大学, 2012.

[55] Wu J, Wang ZW, Shi ZB, et al. The genome of pear(Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd. )[J]. Genome Research, 2013, 23(2):396-408.

[56] Dickinson JR, Harrison SJ, Dickinson JA, et al. An investigation of the metabolism of isoleucine to active amyl alcohol in Saccharomyces cerevisiae[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry,2000, 275:10937-10942.

[57]Beekwilder J, Alvarez-huerta M, Neef E, et al. Functional characterization of enzymes forming volatile esters from strawberry and banana[J]. Plant Physiology, 2004, 135:1865-1878.

(责任编辑 狄艳红)

Research Advance on the Biosynthesis of Volatile Organic Compounds in Plant

Li Fangfang1Tao Shutian1Zhang Huping1,2

(1. College of Horticulture,Nanjing Agricultural University,Nanjing 210095;2. College of Agriculture,Shihezi University,Shihezi 832003)

Plant volatile organic compounds(VOCs)are closely correlative to production and life of human beings. In agriculture, plant volatile organic compounds play important roles in attracting pollinators, defending against biotic and abiotic stress, mediating the exchange of information between plants, giving fruit special scents. In this review, the biosynthesis of terpenoids, phenylpropanoids/benzenoids, fatty acid derivatives and amino acid derivatives were introduced, works and methods in the future were put forward, in an attempt to providing useful information for further studies in the field.

volatile organic compounds;biosynthesis;metabolism;plant

10.13560/j.cnki.biotech.bull.1985.2015.04.003

2014-07-29

国家自然科学基金项目(31260454),国家公益性行业(农业)科研专项(201203080-1)

李芳芳,女,硕士研究生,研究方向:果实品质生理;E-mail:15261871486@126.com

张虎平,博士,副教授,研究方向:果树栽培生理及品质生物学;E-mail:zhanghuping@126.com