Suiyuan 1936:Images of the Anti-Japanese War by Missing Photographer Fang Dazeng

By+Yang+Honglin

In February 1938 when famous war photographer Robert Capa (1913-1954) arrived in China to cover the front lines of the Chinese Peoples War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, his Chinese counterparts had already proved what he believed: “Your photos are not good enough because you are not close enough to the scene.”

Fang Dazeng was a typical legendary photographer. Born around the same time as Capa, Fang left breathtaking photos for later generations after two years of work, framing precious moments in Chinese history. According to eminent Chinese scholar Chen Danqing, Fangs work was no less wonderful than Capas.

Fang Dazeng was born into a diplomatic family in Beiping (Beijing today). He became interested in photography as a child, and taught every technique to himself despite the fact that China lagged far behind the rest of the world in terms of photographic technology.

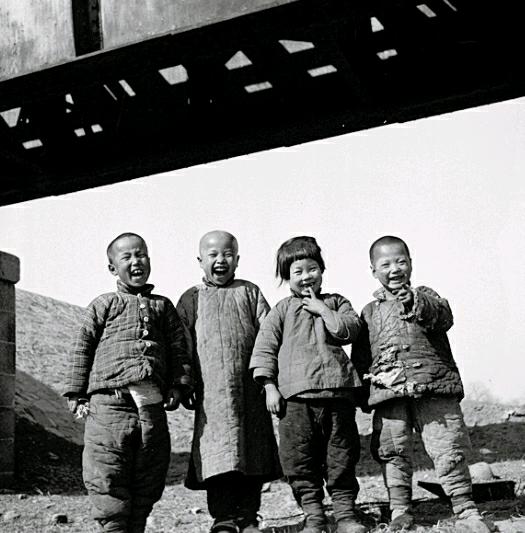

He always focused on Chinese society and common disadvantaged people. In late 1936, the Suiyuan War broke out in todays central Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Fang didnt miss a beat and headed to the front lines alone, where he took pictures amidst the flames of the war for more than 40 days.

After the outbreak of the July 7 Incident of 1937, he headed straight to those front lines, where he was killed three months later.

Eight decades ago, Fang Dazeng was certainly well-known in press and photography circles. As one of the major domestic photographic producers, his penname, Xiao Fang, frequently appeared in prestigious newspapers and journals such as Shen Daily, Eastern Miscellany, World Affairs, and Ta Kung Pao, and his battlefield reports enjoyed a reputation as lofty as those by top Chinese journalists such as Fan Changjiang.

He went silent for the better part of a century before being rediscovered in the 1990s.

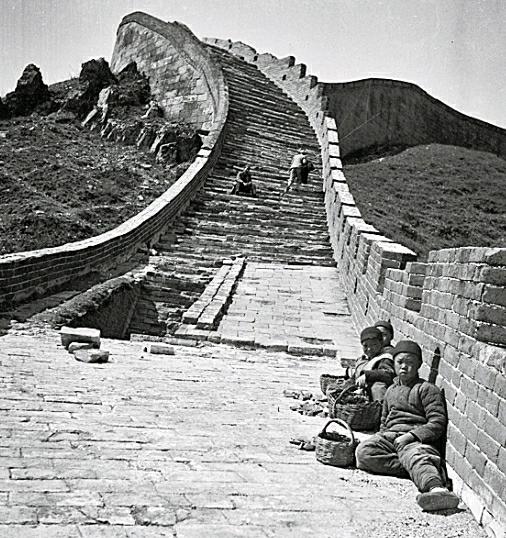

His 837 photos were all acquired by the National Museum of China, the majority of which depict the Suiyuan War in 1936.

Author Yang Honglin “infused” his text about this special chapter of history into Fangs work to spotlight a war legend largely unheralded in contemporary times.

“He seemed to have left behind a 1930s testament for succeeding generations,”opines Yu Hua, a renowned Chinese writer.“The pictures carry us in an old rickety train back to long-lost scenes of wharfs, factories, sailboats draped with ropes, desolate lands, battlefields and weapons, as well as long-outdated modes and styles of days past. The framed figures, faces and eyes are full of eternal vigor and vitality—happy, numb, peaceful, or exciting. His subjects look as sad, exhausted, hurried, or cool as a cucumber—so familiar, similar to what we see today. His work reminds us of truth: Everything fades except for one thing—the faces and silhouettes of people, a constant across generations.”