Nest site characteristics and nest loss of Marsh Grassbird at Zhalong National Nature Reserve,China

Qiang Wang•Xuehong Zhou•Fengshan Li•Yuming Zhang•Feng Li

Nest site characteristics and nest loss of Marsh Grassbird at Zhalong National Nature Reserve,China

Qiang Wang1,2•Xuehong Zhou1•Fengshan Li3•Yuming Zhang1•Feng Li1

The Marsh Grassbird Locustella pryeri is an uncommon songbird endemic to East Asia.Suitable nestsite selection can minimize nest loss,especially for opencup and ground nesting passerines.We located and monitored 66 Marsh Grassbird nests during 2004–2006 in Zhalong National Nature Reserve,northeast China,to identify characteristics of preferred nest sites.Marsh Grassbird nested mainly at sites with dense vegetation cover,high undergrowth and dry standing reed stalks,as well as small shallow ponds or rivers.Nests were more successful when they were placed higher above ground in patches with greaterlitterthickness.Predation and flooding were the leading causes of nest failure,accounting for at least 33 and 25%of 24 nests lost,respectively.We advocate retention of some unharvested reed patches and implementation of irrigation strategies that avoid increasing water levels during the breeding period(May–July)of Marsh Grassbirds.

Flooding·Japanese Marsh Warbler· Locustella pryeri·Nest site·Predation·Zhalong

Introduction

Endemic to East Asia,the Marsh Grassbird Locustella pryeri is strongly associated with wetlands with emergent vegetation(Zheng 1987).Its current status is Near Threatened(BirdLife International 2012).There are two subspecies:the nominate L.p.pryeri breeds in Japan whereas L.p.sinensis breeds in northeast China and possibly in neighboring parts of Russia and Mongolia(Bird-Life International 2001).Information on its population status in China was limited until recently.About 20–25 males were recorded at Zhalong National Nature Reserve, Heilongjiang Province,in June 1987(Shigeta 1991;Bird-Life International 2001).Kanai et al.(1993)counted 15 birds at Shuangtaihekou National Nature Reserve,Liaoning Province,in June 1993 and estimated a maximum of 60 breeding birds in the reserve.In 2007,5000 breeding pairs occurred in the south partof Poyang lake(He etal.2008). Their population in Japan was estimated at 1000 individuals in the 1990s(Kanaiand Ueta 1994,Nakamichiand Ueda 2003).

Although Zhalong National Nature Reserve is an important breeding site for Marsh Grassbird in China,the reserve was designated for and managed primarily to protect endangered Red-crowned Cranes(Grus japonensis) and other large waterbirds,with little attention given to Marsh Grassbirds or other small passerines.Indeed,in China,there are virtually no conservation actions undertaken for rare passerines(Zhao et al.2005),including assessments of nest site quality and protection from nest predators.

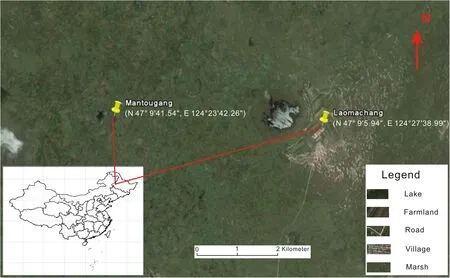

Fig.1 Study area

Nestpredation limits avian fitness,so birds should prefer nest sites that minimize nest loss(Forstmeier and Weiss 2004;Hudson and Bollinger 2013;Latif et al.2012; Schaefer et al.2005).Therefore,nest site selection is a criticalpartof bird breeding ecology,especially for opencup and ground nesting passerines.Managers must have knowledge of the relationship between nest site selection and nest success before undertaking habitat management and conservation.To assistin these managementdecisions, we compared characteristics of nest sites with those of random points.Then evaluated which habitatfeatures were related to breeding success of Marsh Grassbird at Zhalong National Nature Reserve.

Materials and methods

Study site

Zhalong National Nature Reserve(123°47′–124°37′E, 46°52′–47°32′N,total area 2100 km2),located in western Heilongjiang Province,northeastChina,was established in 1985.The reserve is mostly dominated by reed marsh, other common plants including Cattail(Typha orientalis Presl),Scirpus planiculmis,and Scirpus validus.The reserve was established to protect cranes,particularly Redcrowned Crane,as well as other bigger waterbirds and the wetlands.In the reserve,there are many tributaries and ponds with emergent vegetation(i.e.,reeds)along the edges.Many reservoirs,dikes and canals were constructed in and around the reserve over the past decades to meet increasing demands for crop irrigation and the growing human population.Water shortages and droughts have made the wetlands of Zhalong susceptible to fire,with large fires occurring in 2001,2002,and 2005.

Based on yearly bird surveys in Zhalong,we found Marsh Grassbird only at Laomachang and Mantougang. We studied Marsh Grassbirds at these two sites(Fig.1). Both sites are located near the center of the reserve and are difficult to access because of the absence of paths,especially in the rainy season.Most of the reed marshes were managed by the Lindian Reed Company(Heilongjiang, Daqing).Local people who lived in the refuge have contracted with the reed company and own plots of reed mash, so they subsist on reed harvest,cattle raising,and fishing.

Nest searches and observation

During the breeding season,male Marsh Grassbirds frequently sing and perform flight displays to defend their territories.The track of the display-flight is almost vertical and the heightranges from 4 to 10 m.These flightdisplays and songs helped us locate breeding areas.

Nests(Fig.2)were located in Laomachang and Mantougang during the 2004–2006 breeding seasons by observing adults building nests or feeding nestlings. Locations were documented with GPS to facilitate their relocation every 2–3 days.To avoid trampling the vegetation nearnests we observed the nests from a distance of at least 1 meter during nest visits because damage to vegetation within a 1 m radius of nests might have attracted predators.Nest predation was determined either by the disappearance ofthe clutch orofnestlings priorto their anticipated date of fledging(Neto 2006).Otherwise we recorded the nestas successful.

Fig.2 Nest of Marsh Grassbird

Nest-site habitat variables

We measured nest site characteristics,including total vegetation cover,water depth,maximum height and cover of the upper dry reed layer(referred to as upper growth), maximum height and cover of undergrowth(mostly Carex spp.and Scirpus spp.),and height of thatch(maximum height of broken,dead vegetation)within a 1 m radius of nests shortly afterfledging orfailure.Vegetation coverwas estimated visually in the field,from above,in classes of 10%.Human disturbance was recorded as the distance (m)to the nearest potentialdisturbance source,such as dirt road,boat channel,fishing hut,or fishing net and was measured with GPS.The maximum heightof the reeds that had grown in the previous year,rather than the current year’s growth,was measured to eliminate the influence of vegetation growth during the season.Random points were also assessed at the breeding sites,and these did not overlap with the nest site samples(within a 1 m radius of nests).Within Marsh Grassbird nesting areas,a researcher tossed a stone over his shoulder and where it landed we recorded the same variables as for nest sites.72 random points were measured at the two breeding areas during the nesting season of May to August 2004–2006.

Nest measurements included inner and outer diameter, outer depth,depth of the cup,and nestheight(the vertical distance from the upper rim of the nestto the ground).

Data analysis

Mann–Whitney U test was applied to compare the continuous variables,and Chi squared test was applied to discrete variables.A stepwise logistic regression was used to identify the most important features that distinguish nest sites from random points.The log-likelihood of the final modelwas compared with the nullmodelthatonly included the constant with a Chi squared test.To identity habitat variables associated with breeding success,the same statisticalprocedure wasapplied to successfulnestsand failed nests. Allstatisticalanalyseswere performed with SPSS 13.0.

Results and discussion

We located 66 Marsh Grassbird nests,all of which were located in marshes dominated by reeds with Carex spp. Despite Zhalong’s large areas of reed marsh,Marsh Grassbirds were highly localized with Mantougang and Laomachang,the only two areas of Zhalong with similar vegetation conditions.In reed beds,Marsh Grassbird nests were found in reed patches on small,shallow water ponds. Nests were not found in areas that had been completely mowed or burned during the previous year.Nestsites were more likely to be found in areas with greatertotalvegetation cover,greater dry reed height,and greater litter thickness (=114.56,p<0.01).This model correctly classified 90.6%of the nests.The results of the Mann–Whitney and Chisquared tests confirmed the logistic regression results. Dense vegetation cover,high undergrowth,and dry reed height,as well as thick litter,were significantly different between nest-sites and random points(Table 1).Birds chose nest sites with denser vegetation cover and higher dry reed undergrowth and thicker litter which was similar to Marsh Grassbird nestsites in Japan(Kanaiand Ueta 1994;Nagata and Kanai 1994;Li and Wang 2006).The highest nesting densities of Mash Grassbird were associated with high densities ofsedges in reed beds(Kanaiand Ueta 1994;Nagata and Kanai1994;Liand Wang 2006),where reeds and sedges had reached a given height(Kanai and Ueta 1994; Nishide 1994).As a similar species,Savi’s Warblers Locustella luscinioides also preferred sites dominated by tall grass with total vegetation cover,litter thickness,habitat type,undergrowth heightand undergrowth cover allgreater atnest-sites(Neto 2006).

Scattered,dry reed patches were criticalto nest sites of Marsh Grassbirds in China and Japan(Liand Wang 2006; Nishide 1982).First,nests were made mostly of dry reed leaves.Second,mostnests were tangled in the stems of dry reeds;reed stems provided support for the nests and were much stronger than Scripus spp.Carex spp.and other grasses at nesting sites.Third,dry reeds were used frequently as perches or song posts by males(Kanaiand Ueta 1994).Because dry reed was importantforbreeding Marsh Grassbird,we recommend that reeds at Zhalong National Nature Reserve should not be entirely mowed but harvested in a patchy mosaic at the breeding sites.

Table 1 Comparison of habitat conditions(Mean±SE) between random points (n=72)and nestsites(n=66) of Marsh Grassbirds breeding at Zhalong National Nature Reserve,China from 2004 to 2006,using Chi squared test for discrete variables and Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables

Fig.3 The nest after predation

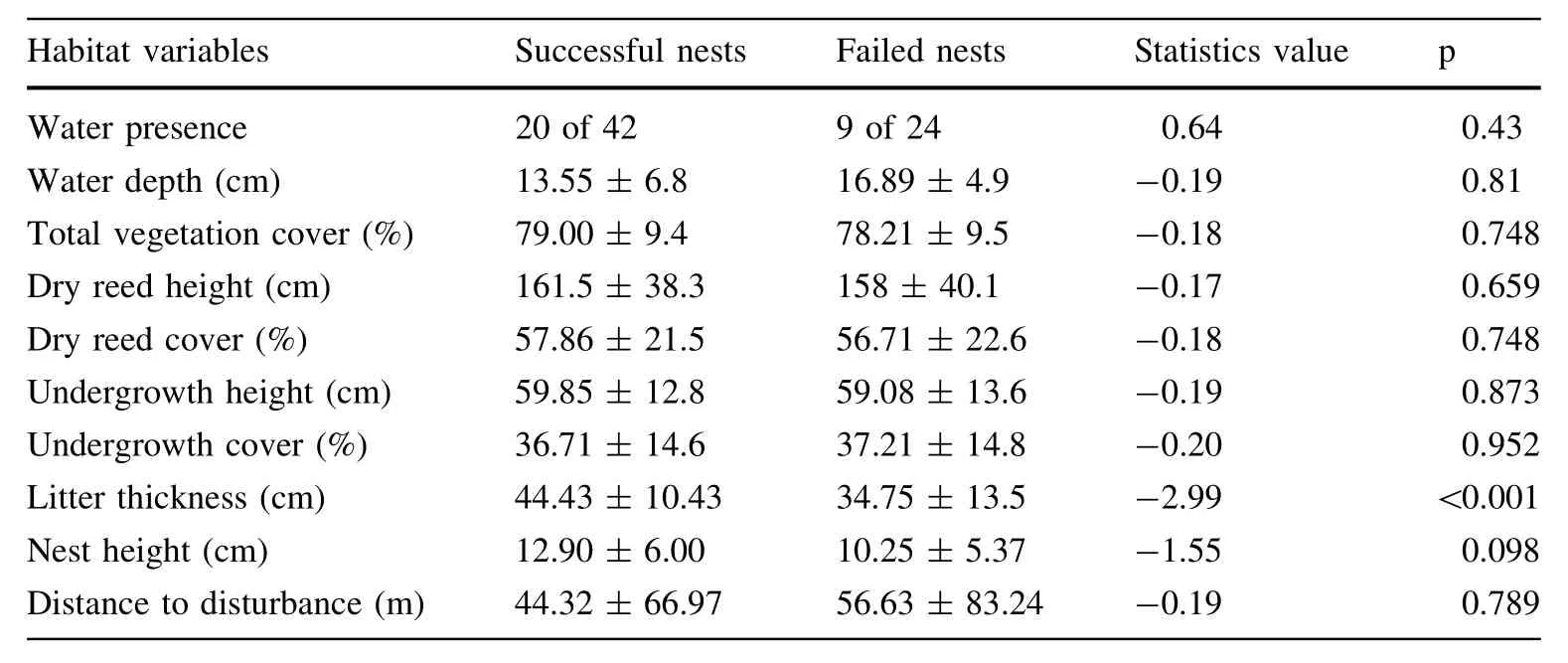

Predation(8 nests,33%,Fig.3)and flooding(6 nests, 25%,Fig.4)accounted for most of the 24 failed nests. Other reasons were abandonment,nests being trampled by cattle and unknown.Litter thickness was greater at successful nests(p<0.01,Table 2).Nest height and litter thickness(=14.53,p=0.01)significantly improved the null model for nest success in a stepwise logistic regression,correctly classifying 68.2%of the cases.

Nest-site characteristics are strongly related to breeding success in birds(Batary and Baldi 2005;Schiegg et al. 2007).Reasons for failed Marsh Grassbird nests included nest predation,flooding,and trampling by cattle.Successful Marsh Grassbird nests were characterized by greater litter thickness and greater nest height.Predation was the leading factor for nest loss.Great Reed Warbler Acrocephalus arundinaceus is a common reed bed bird for which greater nest cover significantly increased the survival of both real and artificial nests,but only during the middle of the breeding season(Batary and Baldi 2005). Nests of Great Reed Warbler in reeds in shallow water reduced the predation risk in comparison with nests on land (Graveland 1999).Reed harvestwas found to be positively correlated with nest predation of Grasshopper Warbler Locustella naevia(Ejsmond 2008).Dense vegetation around the nest of several grassbirds can provide shelter from predation on birds nesting in grassland.In the Zhalong wetlands,reed clear-cutting has destroyed most suitable breeding sites for Mash Grassbird.Before 2002,reeds harvested by the Lindian Reed Company were intended mainly for paper mills and the company collected only tall and strong reeds,leaving short reeds and some small patches of tall reeds intact.However,the marshland was later divided among individual family management units. These local families mowed reeds more extensively and intensively,selling tall reeds to paper mills and burning short reeds as fuel,thereby reducing habitat suitability for Marsh Grassbirds in the nature reserve.

Fig.4 Juvenile killed by flooding

Fire did not destroy any nest directly,but it burned dry reeds thatwere a crucialcomponentof breeding habitatfor Mash Grassbird.There were three large scale fires,mainly due to drought,in Zhalong wetlands in August–December 2001(210 km2),March 2002(42 km2),and May 2005 (4 km2).We assume that the fires had serious negativeeffects on breeding habitat of Mash Grassbird.We witnessed the severity of the fire in 2005 when almost all of the reed marsh at Laomachang was burned.After the fire, Marsh Grassbirds were only found breeding by a pond located behind a dam that was not burned at Laomachang. The Mantougang breeding site was protected by surrounding open water.Where there were no dry reeds there were no nests after the 2005 fire.

Table 2 Comparison of habitat and nestvariables(Mean±SE) for successful nests(n=42) and failed nests(n=24)of Marsh Grassbirds,continuous variables were compared using Mann–Whitney U-tests and discrete variables were compared using Chi squared tests with continuity correction

Predation was the leading factor for loss of Marsh Grassbird nests:potentialpredators include Eastern Marsh Harrier(Circus cyaneus),Pied Harrier(C.melanoleucos), Yellow Weasel(Mustela sibirica),and free-ranging domestic cats(Felis catus)and dogs(Canis lupus familiaris). Other studies also reported that predation was one of the most common causes of nest failure(Allen and Peters 2012;Massaro et al.2013;Fondell and Ball 2004).Nests located at sites with thicker litter may be better protected from predators because the thicker litter limits predator access to the nestand provides increased visualobstruction (Fondell and Ball 2004;Neto 2006).Nest height also influenced predation(Kearns and Rodewald 2013;Massaro et al.2013).In our study,litter thickness and nest height were main factors distinguishing failed from successful nests.

Flooding threatened the breeding of Marsh Grassbird at Zhalong and in Japan(Austin and Kuroda 1953;Kanaiand Ueta 1994).Marsh Grassbirds began nesting at Zhalong in May(Li and Wang 2006),when water depth was nearly 20 cm lower than in June.Because the average nestheight (the vertical distance from the upper rim of the nest to the ground)was no more than 15 cm,nests were very low in a narrow beltalong rivers or ponds.In some areas high water periods can cause severe losses(Aebischer and Antoniaza 1995).

In Japan,Marsh Grassbird faces a similar problem. Wetland reclamation and water projects exacerbate the effects of drought on wetlands,and in turn droughts decrease vegetation cover and reduce the area of suitable breeding habitats for Marsh Grassbird(Nishide 1982).In response to droughts from 2002 to 2006,the local government irrigated Zhalong National Nature Reserve. Although irrigation projects have mitigated drought conditions in many reserves,water can have both beneficial and detrimental effects on birds(Borad etal.2002;Gilbert and Servello 2005;Liu et al.2006;Mukherjee et al.2002; Nielsen and Gates 2007;Nishide 1982,1994;Poiani2006; Sanders and Maloney 2002)The timing of irrigation appears criticalto successfulnesting of Marsh Grassbird.We recommend avoiding large and sudden increases in water depth during the breeding period of birds nesting on or near ground level.In Zhalong National Nature Reserve,a reasonable irrigation scheme could not only reduce the fire danger for our study site,but also avoid flooding the nests of Marsh Grassbird.

Conclusions

Marsh Grassbird nests were located in marshes dominated by reeds with Carex spp.butnotby cattail Typha orientalis or other emergent plants.Marsh Grassbird nests were found in reed patches around small,shallow ponds and rivers.Nests were not found in areas that had been completely mowed or burned during the previous year.More nests were found in patches with dense vegetation cover, tall undergrowth and dry,standing reed stalks,as well as along small shallow ponds or rivers.Nest success was greaterwhen nests were constructed in patches with greater litter thickness and placed higher above ground.Reasons for failed Marsh Grassbird nests included nest predation, flooding,and trampling by cattle.Predation and flooding were the leading causes of nest failure,accounting for at least 33 and 25%,respectively,of 24 nests lost.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank WANG Y and MOORE SG for reviewing the manuscript.We also thank CAI YJ,FU JG and BA YB, and Zhalong National Nature Reserve for assistance in field investigations.

Open AccessThis article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use,distribution,and reproduction in any medium,provided the original author(s)and the source are credited.

Aebischer A,Antoniaza M(1995)Distribution and population fluctuations of the Savvy’s Warbler Locust Ella luscinioides in Switzerland.Onithologische beobachter 92:435–453

Allen MC,Peters KA(2012)Nestsurvival,phenology,and nest-site characteristics of common nighthawks in a new jersey pine barrens grassland.Wilson J Ornithol 124:113–118

Austin OL,Kuroda N(1953)The birds of Japan,their status and distribution.Bull Mus Comp Zool 109:277–637

Batary P,Baldi A(2005)Factors affecting the survival of real and artificial greatreed warbler’s nests.Biologia 60:215–219

BirdLife Interantional 2012.Locustella pryeri.The IUCN red list of threatened species.version 2014.3.www.iucnredlist.org.Accessed 13 Feb 2015

BirdLife International(2001)Threatened birds of Asia:the BirdLife international red data book.BirdLife International,Cambridge

Borad CK,Mukherjee A,Patel SB,Parasharya BM(2002)Breeding performance of Indian Sarus Crane Grus antigone antigone in the paddy crop agroecosystem.Biodivers Conserv 11:795–805

Ejsmond MJ(2008)The effect of mowing on next-year predation of grassland bird nests:experimentalstudy.Pol J Ecol56:299–307

Fondell TF,Ball IJ(2004)Density and success of bird nests relative to grazing on western Montana grasslands.Biol Conserv 117:203–213

Forstmeier W,Weiss I(2004)Adaptive plasticity in nest-site selection in response to changing predation risk.Oikos 104:487–499

Gilbert AT,Servello F(2005)Water level dynamics in wetlands and nesting success of Black Terns in Maine.Waterbirds 28:181–187

Graveland J(1999)Water reed,marsh birds and natural water level fluctuations.Levende Nat 100:50–53

He FQ,Lin JS,Huang XJ,Dong WX(2008)Preliminary reporton the Poyang lake breeding subpopulation of the March grassbird in Jiangxi of central south China.Chin J Zool 43:70–72

Hudson NC,Bollinger EK(2013)Nestsuccess and nestsite selection of red-headed woodpeckers(Melanerpes erythrocephalus)in east-central Illinois.Am Midl Nat 170:86–94

Kanai YL,Ueta M(1994)The present distribution and habitat of Japanese Marsh Warbler.In:Wild Bird Society of Japan,survey of the status and habitat conditions of threatened species,1993. Report to the Environment Agency of Japan,p 1–7

Kanai YL,Jin K,Hayashi H(1993)Avifauna and conservation of Liaoning Shangtai Hekou Nature Reserve.Strix 12:145–160

Kearns LJ,Rodewald AD(2013)Within-season use of public and private information on predation risk in nest-site selection. J Ornithol 154:163–172

Latif QS,Heath SK,Rotenberry JT(2012)How avian nest site selection responds to predation risk:testing an‘adaptive peak hypothesis’.J Anim Ecol 81:127–138

Li F,Wang Q(2006)Breeding biology of Japanese marsh warbler’s sinensis subspecies.Acta Zool Sin 52:1162–1168

Liu SL,Cai YJ,Pang SL,Qiu FC,He CG,Song YJ(2006)The influence of water resource condition on rare waterfowl in Zhalong National Nature Reserve.J Northeast Norm Univ 38:105–108(Natural Science Edition)

Massaro M,Stanbury M,Briskie JV(2013)Nestsite selection by the endangered black robin increases vulnerability to predation by an invasive bird.Anim Conserv 16:404–411

Mukherjee A,Borad CK,Parasharya BM(2002)Breeding performance of the Indian sarus crane in the agriculturallandscape of western India.Biol Conserv 105:263–269

Nagata H,Kanai Y(1994)The arrangement of male territories and the microhabitat preference of Japanese Marsh warbler in the flood plain of Tonegawa River,Kamisu.In:Wild Bird Society of Japan,Survey of the status and habitat conditions of threatened species,1993.Report to the Environment Agency of Japan, p 24–29

Nakamichi R,Ueda K(2003)Recentstatus and habitatpreference of the Japanese marsh warbler at Hotoke-numa marsh,northern Honshu,Japan.Strix 21:5–14

Neto JM(2006)Nest-site selection and predation in Savi’s Warblers Locustella luscinioides.Bird Study 53:171–176

Nielsen CLR,Gates RJ(2007)Reduced nest predation of cavitynesting Wood Ducks during flooding in a bottomland hardwood forest.Condor 109:210–215

Nishide T(1982)The survey of the Japanese Marsh Warbler Megalurus pryeri on Hachirogata reclaimed land,Akita prefecture 2.changes in habitat distribution.Strix 1:7–18

Nishide T(1994)The population status of Japanese Marsh Warbler in Hachirogata reclaimed farmland.In:Wild Bird Society of Japan, Survey of the status and habitatconditions of threatened species, 1993.Report to the Environment Agency of Japan,p 36–47

Poiani A(2006)Effects of floods on distribution and reproduction of aquatic birds.Adv Ecol Res 39:63–83

Sanders MD,Maloney RF(2002)Causes of mortality at nests of ground-nesting birds in the Upper Waitaki Basin,South Island, New Zealand:a 5-year video study.Biol Conserv 106:225–236

Schaefer HC,Eshiamwata GW,Munyekenye FB,Griebeler EM, Bo¨hning-Gaese K(2005)Nest predation is little affected by parental behaviour and nest site in two African Sylvia warblers. J Ornithol 146:167–175

Schiegg K,Eger M,Pasinelli G(2007)Nest predation in reed buntings Emberiza schoeniclus:an experimental study.Ibis 149:365–373

Shigeta Y(1991)Identification guide 2.The Japanese Marsh Warbler; birds with a vestigial claw on the wing.Nihon no Seibutu 5:48–51

Zhao HF,Gao XB,Lei FM,Liu XY,Zheng N,Yin ZH(2005)On the status and distribution of threatened birds of China.Biodivers Sci 13:12–19

Zheng ZX(1987)A synopsis ofthe Avifauna of China.Science Press, Beijing

3 November 2013/Accepted:13 January 2014/Published online:12 May 2015

©The Author(s)2015.This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com

Projectfunding:This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(Grant No.30370221;41310302; 41001026)and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China(Grant No.DL12CA09).

The online version is available at http://www.springerlink.com

Corresponding editor:Hu Yanbo

✉Feng Li lifeng604@163.com

1College of Wildlife Resource,Northeast Forestry University, Harbin 150040,China

2Key Laboratory of Wetland Ecology and Environment,CAS, Changchun 130012,China

3International Crane Foundation,E-11376 Shady Lane Road, Baraboo,WI 53913,USA

Journal of Forestry Research2015年3期

Journal of Forestry Research2015年3期

- Journal of Forestry Research的其它文章

- Management of pests and diseases of tropical sericultural plants by using plant-derived products:a review

- Gamma generalized linear model to investigate the effects of climate variables on the area burned by forest fire in northeast China

- Diversity,abundance,and structure of tree communities in the Uluguru forests in the Morogoro region,Tanzania

- Brazilian savanna re-establishment in a monoculture forest: diversity and environmental relations of native regenerating understory in Pinus caribaea Morelet.stands

- Carbon storage and sequestration rate assessment and allometric model development in young teak plantations of tropical moist deciduous forest,India

- Use of infrared thermal imaging to diagnose health of Ammopiptanthus mongolicus in northwestern China