Insights into the differences in leaf functional traits of heterophyllous Syringa oblata under different light intensities

Hongguang Xiao•Congyan Wang•Jun Liu•Lei Wang•Daolin Du,2

Insights into the differences in leaf functional traits of heterophyllous Syringa oblata under different light intensities

Hongguang Xiao1•Congyan Wang1•Jun Liu1•Lei Wang1•Daolin Du1,2

Many plants exhibit heterophylly;the spatially and temporally remarkable ontogenetic differences in leaf morphology may play an adaptativerolein theirsuccessunder diverse habitats.Thus,this study aimed to gain insights into differencesin leaffunctionaltraits ofheterophyllous Syringa oblata Lindl.,which has been widely used as an ornamental tree around the world underdifferentlightintensities in East China.No significantdifferences existed in specific leafarea (SLA)between lanceolate-and heart-shaped leaves.Differences in the investmentper unitof lightcapture surface area deployed between lanceolate-and heart-shaped leavesmay benotobvious.This may be attributing to the factthatsingle leaf wetand dry weightofheart-shaped leaves were significantly higherthan those oflanceolate leavesbutleaflength and leaf thicknessofheart-shaped leaveswere significantly lowerthan those oflanceolate leaves.The SLA of shade trees was significantly higherthan thatofsun trees.Theinvestmentperunit oflightcapture surface ofshade trees was lowerthan thatof sun trees,making itpossible to increase lightcapture and use efficiency in low-light environments.The phenotypic plasticity of most leaf functional traits of lanceolate leaves was higherthan those ofheart-shaped leaves because the formeris the juvenile and the latter is the adultleaf shape during the processofphylogenetic developmentof S.oblate.The higher range of phenotypic plasticity of leaf thickness and leaf moisture for sun trees may be beneficial to obtain a more efficientcontrolofwaterlossand nutrientdeprivation in highlight environments,and the lower range of phenotypic plasticity of single leaf wet and dry weight,and SLA for shade trees may gain an advantage to increase resource(especially light)capture and use efficiency in low-lightenvironments.In brief,thesuccessfully ecologicalstrategy ofplantsisto find an optimal mode for the trade-off between various functional traitsto obtain more living resourcesand achieve morefitness advantage as much as possible in the multivariate environment.

Heterophylly·Light intensity·Specific leaf areas·Syringa oblata Lindl.

Introduction

Since leaves are exposed to and sensitive to environmental changes,the response of leaf functionaltraits to changes in environmentalfactors could enable plants to occupy a widevariety of environmentalconditions and thereby reflectthe successful ecological strategy of plants during their life cycle(Poorter et al.2009;Campitelli and Stinchcombe 2013).

Many plants exhibit heterophylly,which refers to the leaf component of heteroblasty,i.e.,variations in the size and shape of leaves produced along the axis of an individual plant during their life cycle(Pardos et al.2009; Tanaka-Oda et al.2010;Leigh et al.2011;Momokawa et al.2011).The spatially and temporally remarkable ontogenetic differences in leaf morphology may play an adaptative role in their success under diverse habitats (Pardos et al.2009;Tanaka-Oda et al.2010;Leigh et al. 2011;Momokawa et al.2011)because their leaf morphology could trigger pronounced effects on leaf functions (Pardos et al.2009;Leigh et al.2011;Momokawa et al. 2011).

Given that leaf functional traits and the heterophylous phenomenon may be all affected by environment factors (especially light intensity)(Burns and Beaumont 2009; Momokawa et al.2011;Yang et al.2014),understanding the differences in leaf functional traits of heterophylly of plants under different light intensities is necessary to elucidate the mechanism underlying their successful ontogenetic strategies.Unfortunately,existing studies on heterophylous plants mainly focus on hydrophyte butoften ignore terrestrial species(except for the gymnospermous species Ginkgo biloba L.).

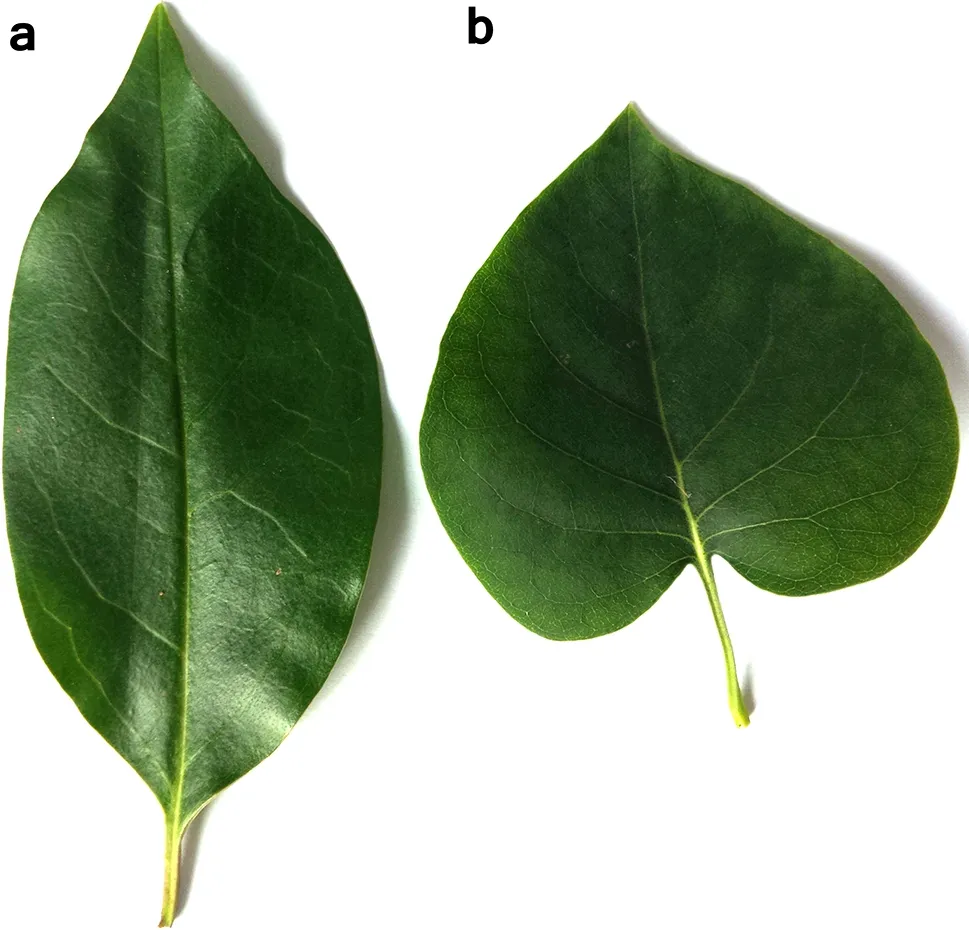

This study was conducted using cross-site comparisons to elucidate the differences in leaf functional traits of heterophylly(two leaf forms:lanceolate and heartshaped leaves,Fig.1)Syringa oblata Lindl.(abbreviated as S.oblata hereafter)under different light intensities (i.e.low and high light).S.oblata has been widely used as an ornamental tree around the world.The leaf functional traits[i.e.,leaf size,leaf thickness,the ratio of leaf length to petiole length,leaf shape index,single leaf wet and dry weight,leaf moisture,specific leaf area(SLA)] of the two leaf forms of S.oblata were assessed to provide insights into the ontogenetic strategy of heterophyllous S.oblata under different light intensities.

The following hypotheses were presented:

(1)SLA of lanceolate leaves(juvenile)was higher than that of heart-shaped leaves(adult),but leaf thickness,and the single leaf wet and dry weight of lanceolate leaves was conspicuously lower than those ofheart-shaped leaves because SLA decreased and leafthickness increased during leafdevelopment (Mediavilla and Escudero 2009;Battie-Laclau et al. 2014).

Fig.1 The two leafforms ofheterophyllous Syringa oblata.Legend: a lanceolate leaves,b heart-shaped leaves

(2)Leaf thickness,and single leaf wetand dry weightof sun trees(under high light intensity)were significantly higher than those of shade trees(under low lightintensity).By contrast,leaf size,leaf moisture, and SLA of sun trees were obviously lower than those of shade trees because sun trees have greater quantities of material investment per unit area in order to obtain a more efficient control of water loss and nutrient deprivation in high-light environments. Shade trees also have less material investment per unit area in order to increase resource(especially light)capture and use efficiency in low-light environments(Burns and Beaumont2009;McIntyre and Strauss 2014;Yang et al.2014);and

(3)Leaf thickness,and single leaf wet and dry weight were negatively correlated with SLA,while leaf size and leaf moisture were positively correlated with SLA because the leaves with high SLAs provide low structural investment,but leaves with low SLAs likely invest great biomass on leaf structures (Poorter etal.2009;Pietsch etal.2014).

Materials and methods

Experimental design

In June 2014,samples of heterophyllous plant S.oblata were obtained from two sites in Zhenjiang,People’sRepublic of China[the samples under high and low light were collected from open areas(32°20′N,119°51′E)and shaded areas(32°20′N,119°52′E),respectively].A totalof 14 plant samples from each site were collected to determine plant characteristics.In one plant sample,five adult and intact leaves of each leaf shape of one plant sample were selected randomly.The physiochemicalproperties of soilsamples from each planting site were also determined. Sampling was completed in 2 days.

Determination of plant characteristics and soil physiochemical properties

The characteristics related to plantperformance and fitness were determined.Crown diameter,breastdiameter,petiole diameter,and leaf thickness were calculated using a Vernier caliper with an accuracy of 0.01 mm.

Leaf shape index was calculated as the ratio of leaf length to the corresponding leaf width(Jeong et al.2011; Wang and Zhang 2012).Leaf length is the maximum value along the midrib,and width is the maximum value perpendicular to the midrib(Wang and Zhang 2012).Leaf length and leaf width were measured using a ruler.

The ratio ofleaflength to petiole length was determined using the ratio ofthe leaflength to the corresponding petiole length.

Leaf moisture was calculated by subtracting dry leaf weight from leaf wet weight;the difference was then divided by wet leaf weight.Single wet leaf weight was determined using an electronic balance.Single dry leaf weightwas obtained by initially drying the samples to in an oven setat60°C for24 h to achieve a constantweight;the final single dry leaf weight was then determined using an electronic balance with an accuracy of 0.001 g.

To estimate SLA,ten leafdiscswith adefiniteareaperleaf shape were cutfrom adultand intactleaves by using a borer with a definite diameter.The main leafveins were carefully avoided during coring to reduce sample variation.The collected leaf discs were stored in small parchment bags, transported to the laboratory 12 h,and oven-dried at60°C for 24 h to obtain a constant weight determined using an electronic balance with an accuracy of 0.001 g.SLA was calculated by dividing leafarea by thecorresponding leafdry weight(cm2g-1)(Kardeletal.2010;Scheepensetal.2010).

The plasticity index and relative distance plasticity index [the two indices ranged from zero(no plasticity)to one (maximum plasticity)]offunctionaltraits of heterophyllous S.oblata under different light intensities were calculated according to the previously described methods in Valladares etal.(2006),Chen etal.(2013),and Lamarque etal.(2013).

Soil pH values and moisture levels were all measured using a soil acidity-moisture meter[ZD instrument(ZD-06),People’s Republic of China].

Statistical analysis

Data were evaluated to determine deviations from normality and homogeneity of variance before data analysis. Differences among various dependent variables were assessed using analysis of variance.Two-way ANOVAs was applied to evaluate the effects of leaf shape and light intensity on leaf functional traits and soil physiochemical properties of S.oblata.Statistically significant differences were set at P values equal to or lower than 0.05.Patterns between various dependent variables were performed by correlation analysis using SPSS(version 17.0).

Results

Leaf functional traits and soil physiochemical properties of heterophyllous S.oblata

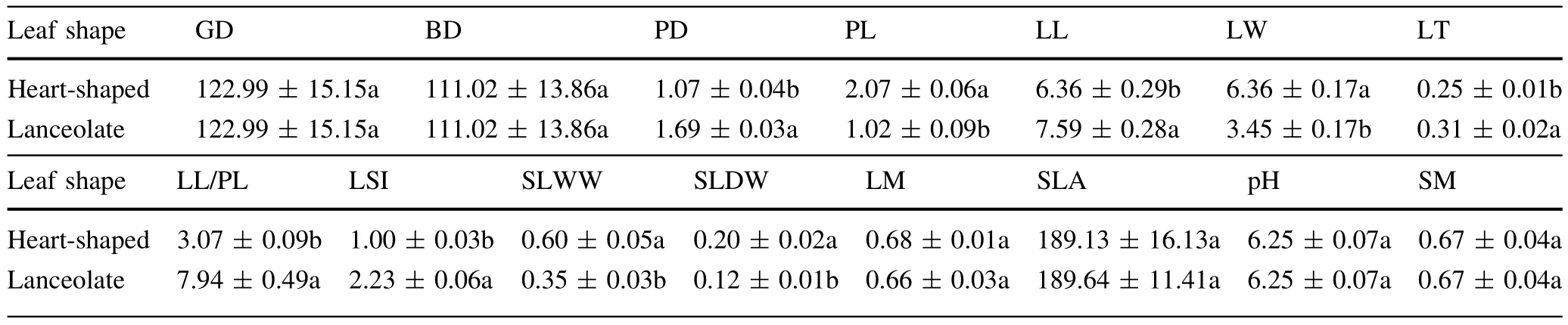

For heart-shaped leaves,petiole diameter,leaf length,leaf thickness,the ratio of leaf length to petiole length,and leaf shape index were all significantly lower than those of lanceolate leaves(Table 1,P<0.05)butthe opposite was true for petiole length,leaf width,and single leaf wet and dry weight(Table 1,P<0.05).Other indices were not significantly differentbetween lanceolate and heart-shaped leaves(Table 1,P>0.05).

Leaf functional traits and soil physiochemical properties of S.oblata under the two light intensities

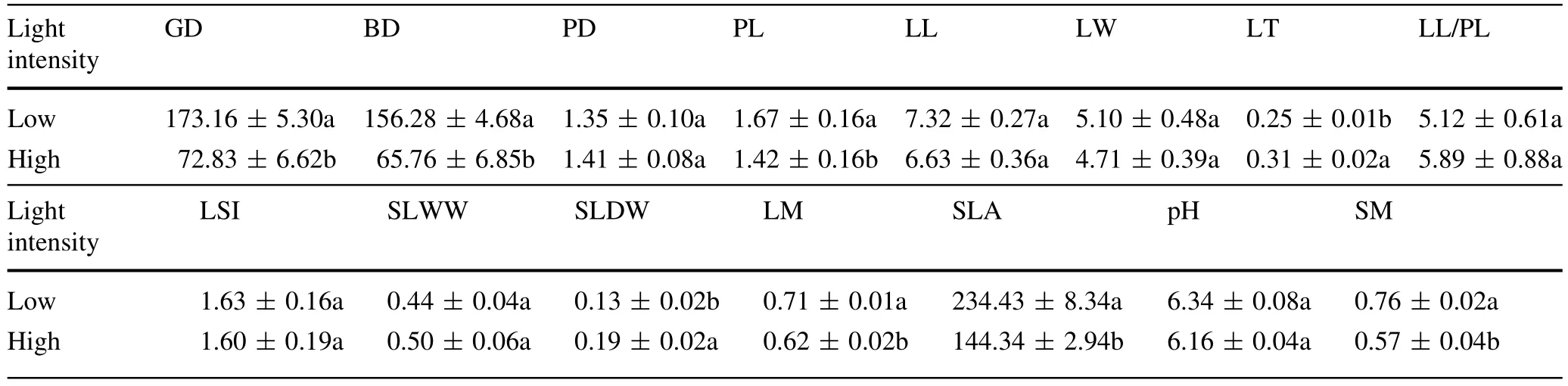

Leaf thickness and single-leaf dry weightof sun trees were higher than those of shade trees(Table 2,P<0.05).By contrast,ground diameter,breast diameter,petiole length, leaf moisture,SLA,and soil moisture of shade trees were higher than those of sun trees(Table 2,P<0.05).There was no significant difference in other indices between of sun and shade trees(Table 2,P>0.05).

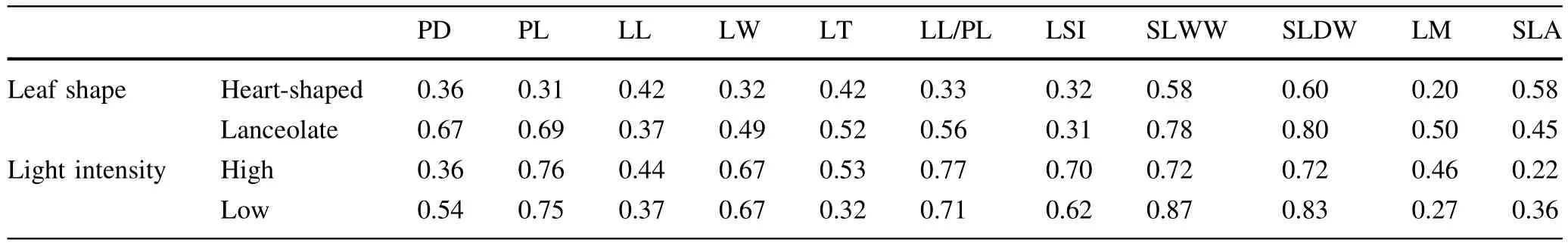

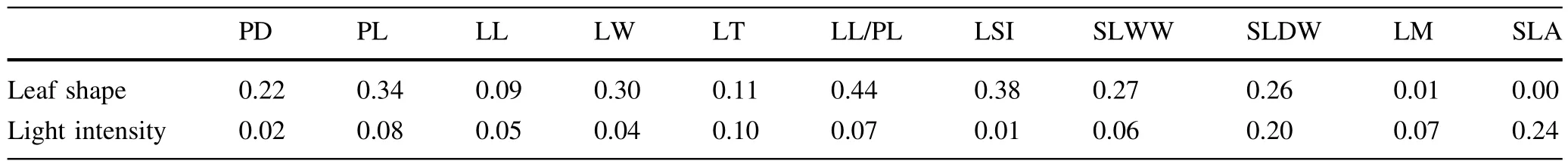

The effects of leaf shape and light intensity on leaf functional traits and soilphysiochemical properties of S.oblata

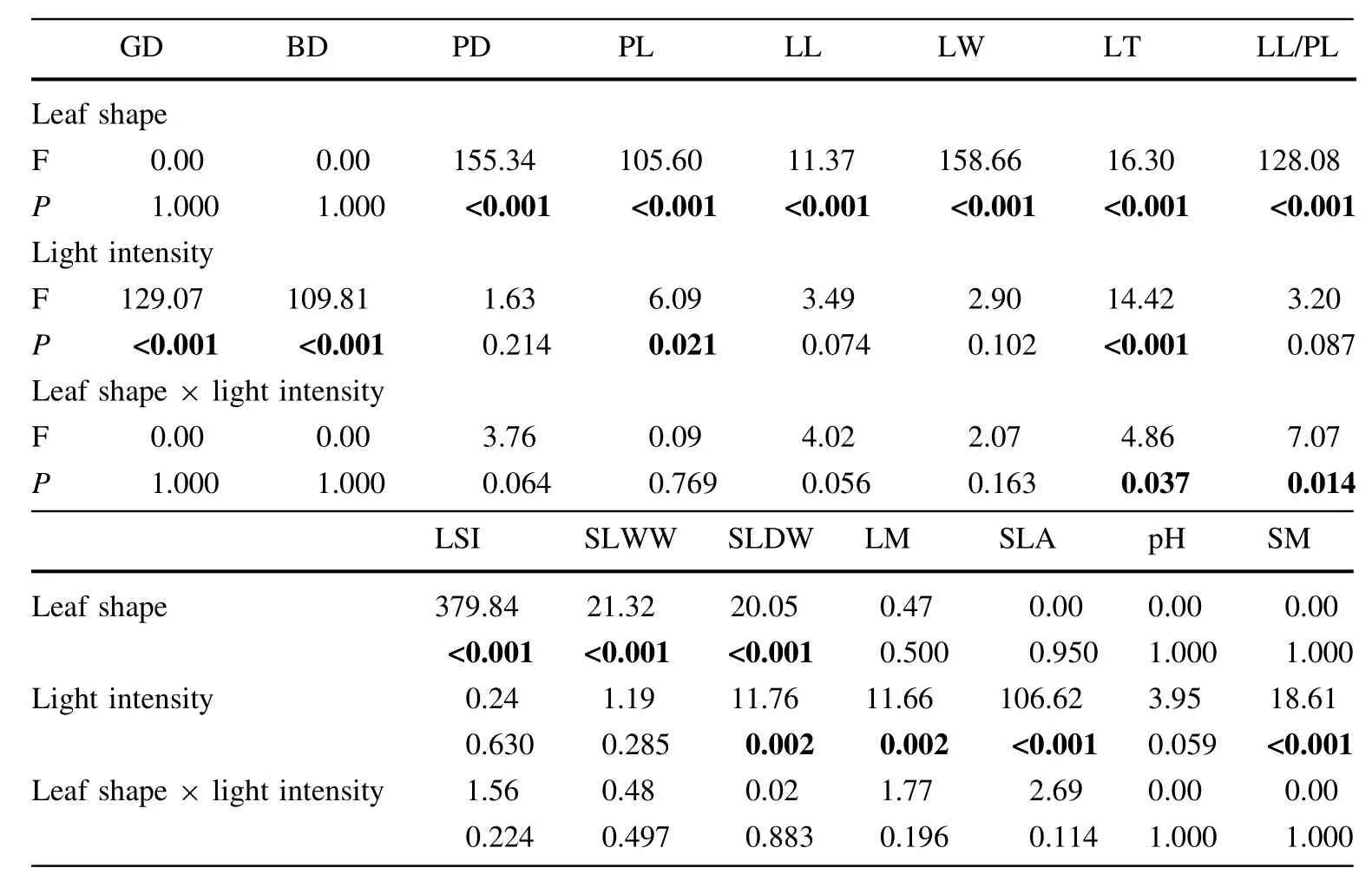

ANOVA results revealed that leaf shape significantly affected petiole diameter,petiole length,leaf length,leaf width,leaf thickness,the ratio of leaf length to petiole length,leaf shape index,and single leaf wetand dry weight (Table 3,P<0.001).However,leaf shape did not pose obvious effects on otherindices(Table 3,P>0.05).Light intensity significantly affected ground diameter,breast diameter,petiole length,leaf thickness,single leaf dry weight,leaf moisture,SLA,and soil moisture(Table 3, P<0.05)but not other indices(Table 3,P>0.05).Theinteractions of leaf shape and light intensity have significant effects on leaf thickness and the ratio of leaf length to petiole length only(Table 3,P<0.05).

Table 1 Differences in leaf functional traits and soil physiochemical properties of heterophyllous Syringa oblata

Table 2 Differences in leaf functional traits and soil physiochemical properties of Syringa oblata under different light intensities

Plasticity index and relative distance plasticity index of leaf functional traits of heterophyllous S.oblata under different light intensity

The plasticity index of SLA of heart-shaped leaves was obviously higher than that of lanceolate leaves(Table 4). In specific,the plasticity index of petiole diameter,petiole length,leaf width,leaf thickness,the ratio of leaf length to petiole length,single leaf wet and dry weight,and leaf moisture of lanceolate leaves were obviously higher than those of heart-shaped leaves(Table 4).The difference in plasticity index ofleaflength and leafshape index between lanceolate and heart-shaped leaves was not obvious (Table 4).The plasticity index of leaf thickness and leaf moisture of sun trees were certainly higher than those of shade trees butthe opposite for petiole diameter,single leaf wet and dry weight,and SLA(Table 4).There was no significantdifference in the plasticity index of other indices between of sun and shade trees(Table 4).Relative distance in the plasticity index of petiole diameter,petiole length, leaf width,the ratio of leaf length to petiole length,leaf shape index,and single leaf wet weight for different leafshape environments were obviously lower than those for the different light intensity but the opposite for SLA (Table 5).The difference in the relative distance plasticity index(of other indices)between different leaf shapes and light intensities was not obvious(Table 5).

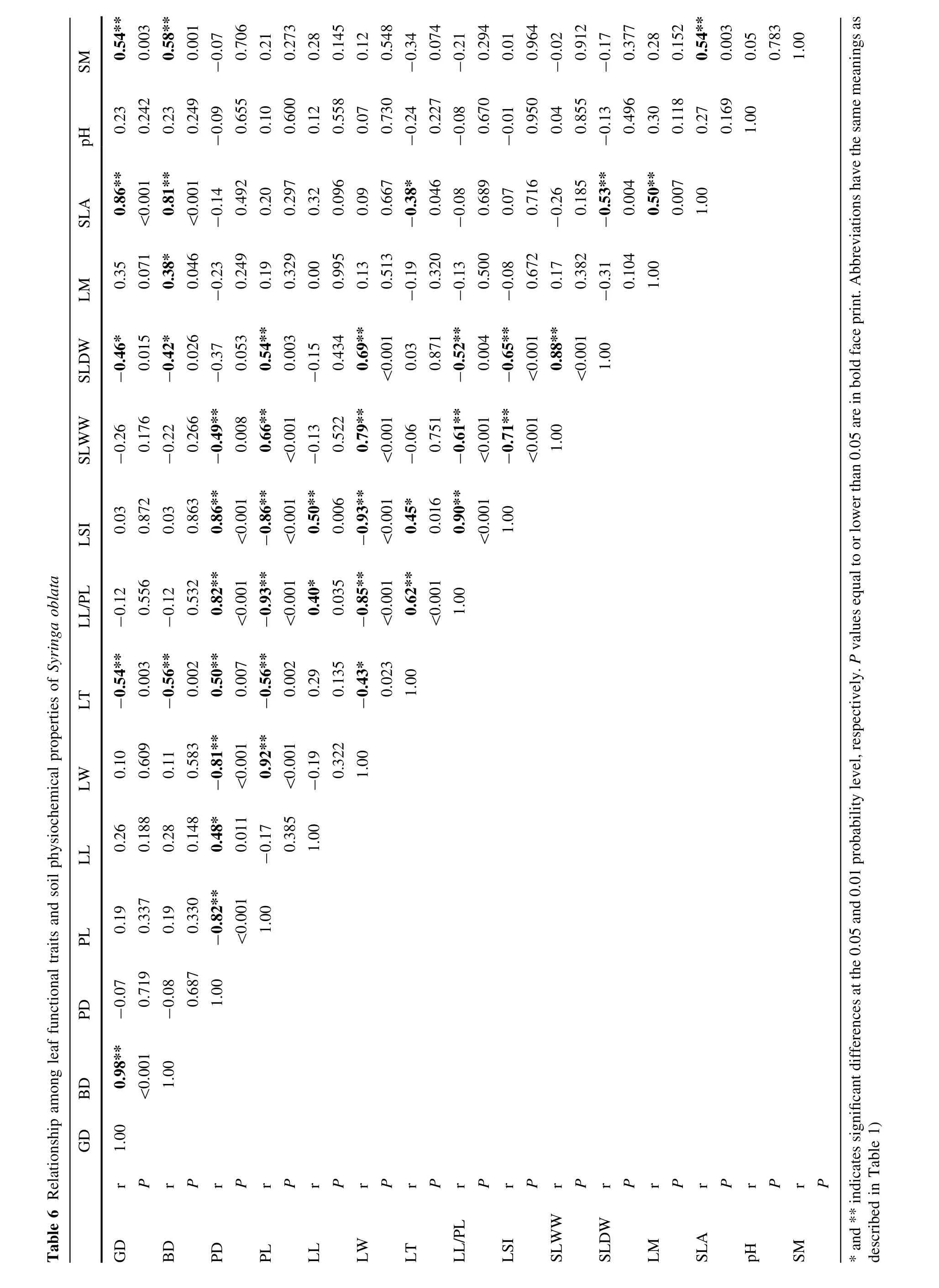

Relationship between leaf functional traits and soil physiochemical properties of S.oblata

Correlation patterns between leaf functional traits and soil physiochemicalproperties ofheterophyllous S.oblate were observed.In particular,ground diameter was positively correlated with breast diameter,SLA,and soil moisture (Table 6,P<0.01)but negatively correlated with leaf thickness(Table 6,P<0.01).Likewise,breast diameter was positively correlated with leaf width,SLA,and soil moisture(Table 6,P<0.05)but negatively correlated with leaf thickness and single leaf dry weight(Table 6,P<0.05);petiole diameter was positively correlated with leaf length,leaf thickness,the ratio of leaf length to petiole length,and leaf shape index(Table 6,P<0.01)but negatively correlated with petiole length,leaf width,and single leaf wet weight(Table 6,P<0.01);petiole length was positively correlated with leaf width,and single leaf wet and dry weight(Table 6,P<0.01)but negatively correlated with leaf thickness,the ratio of leaf length to petiole length,and leaf shape index(Table 6,P<0.01).Leaf length was positively correlated with the ratio ofleaflength to petiole length and leaf shape index(Table 6,P<0.05); leaf width was positively correlated with single leaf wet and dry weight(Table 6,P<0.001)but negatively correlated with leafthickness,the ratio ofleaf length to petiole length,and leaf shape index(Table 6,P<0.05).Leaf thickness was positively correlated with the ratio of leaf length to petiole length and leaf shape index(Table 6, P<0.05)but negatively correlated with SLA(Table 6, P<0.05);the ratio of leaf length to petiole length was positively correlated with leaf shape index(Table 6,

P<0.001)but negatively correlated with single leaf wet and dry weight(Table 6,P<0.01);leaf shape index was negatively correlated with single leaf wet and dry weight (Table 6,P<0.001);single leaf wetweightwas positively correlated with single leaf dry weight(Table 6, P<0.001);single leaf dry weight was negatively correlated with SLA(Table 6,P<0.01)but leaf moisture was positively correlated with SLA(Table 6,P<0.01);and SLA was positively correlated with soilmoisture(Table 6, P<0.01).

Table 3 Two-way ANOVAs on the effects of leaf shape and lightintensity on leaf functional traits and soil physiochemical properties of Syringa oblata

Table 4 Plasticity index of leaf functional traits of heterophyllous Syringa oblata under different light intensities

Table 5 Relative distance plasticity index of leaf functional traits of heterophyllous Syringa oblata under different light intensities

Discussion

Previous studies found an obvious difference in the leaf functional traits between different leaf shapes of heterophyllous species.For example,the northern temperate gymnosperm G.biloba has two leaf types borne on different kinds of shoots(short-shoots leaves and long-shoot leaves)and short-shoot leaves were thinner and had higher vein density,lower stomatal pore index,smaller bundle sheath extensions and lower hydraulic conductance than long-shoot leaves(Leigh et al.2011).Meanwhile,Sabina vulgaris is a heterophyllus tree with two leafforms:needle leaves and scale leaves,and scale leaves had a larger leaf mass area,higher leaf area-based photosynthetic rate, higher water-use efficiency,and stronger tolerance of photoinhibition compared to needle leaves(Tanaka-Oda etal.2010).The differences in leaf morphology may play a key role in their successful survival(Pardos et al.2009; Tanaka-Oda et al.2010;Leigh et al.2011;Momokawa et al.2011).Because SLA decreased and leaf thickness increased during leaf development(Mediavilla and Escudero 2009;Battie-Laclau et al.2014),the SLA of lanceolate leaves may be higher than that of heart-shaped leaves,but opposite for leaf thickness.The result of this study indicates that the difference in the investment per unit of light capture surface deployed between lanceolate and heart-shaped leaves may be not obvious.This result is inconsistent with our first hypothesis.This phenomenon may be attributing to the fact that single leaf wet and dry weight of heart-shaped leaves were significantly higher than those of lanceolate leaves but leaf length and leaf thickness of heart-shaped leaves were significantly lower than those of lanceolate leaves.

Meanwhile,petiole diameter,leaf length,leaf thickness, the ratio of leaf length to petiole length,and leaf shape index of heart-shaped leaves were significantly lower than those of lanceolate leaves,but opposite for petiole length, leaf width,and single leaf wetand dry weight.This means lanceolate leaves differmorphologically from heart-shaped leaves.This result may be attributed to the difference in growth stage of the two leaf shapes because the former is the juvenile and the latter is the adult.The reason may also be as a resultof the difference in survivalenvironment,i.e., the location of the former is lower than thatof the latterand thus receives relatively less acceptable light.For example, the higher the ratio of leaf length to petiole length of lanceolate leaves than that of heart-shaped leaves may indicate that juvenile lanceolate leaves may invest more biomass on lamina structures rather than petiole to capture light with a maximum efficiency.

Lightis one ofthe mostimportantecologicalfactors that affect plant establishment,growth,and survival,particularly for understory species(Liu et al.2010;Meng et al. 2014).Thus,shade trees may pay less material investment per unit area so as to increase light capture and use efficiency in low-light environments(Burns and Beaumont 2009;McIntyre and Strauss 2014;Yang etal.2014).Shade trees also may make an utmost effort in order to increase light capture efficiency by producing thin,high area,and less tough leaves with high SLAs(Rozendaal et al.2006). Clearly,the material investment per unit area(SLA)and per lamina(single leaf dry weight)of shade trees were significantly lower than that of sun trees.Meanwhile,the petiole length and leaf moisture of shade trees was also significantly lower than those of sun trees butopposite for leaf thickness.In addition,leaf size(leaf length and leaf width as the indicator)of shade trees was higher than that of sun trees and single leaf wet weight of shade trees was lower than sun trees although not substantially.This may be due to that larger leaf size allows the plants to gain height more rapidly because fewer woody branches and lower twig biomass are required to support the larger smaller leaves(Sun et al.2006);that said,longer petioles are needed to avoid self-shading(Pearcy etal.2005).

Increases in leaf size are often bound to enhanced biomass investment in the petiole,and may also bring about larger fractional biomass allocation in the midrib(Niinemets and Sack 2006).Results obtained in this study thereby are only partly consistent with the second hypothesis.Generally,shade trees may possess many functional traits,such as less leaf thickness,high petiole length,high leaf moisture,and high SLAs,which can allows shade trees to gain a competitive advantage in lowlight environments according to the results of this study and also previous studies(Rozendaalet al.2006;Liu et al. 2010;Meng et al.2014).

Since any functional traits that contribute a fitness advantage to a species in its environment will be under selection pressure and may thus evolve,phenotypic plasticity should be a potential target for selection(Poorter et al.2009;McIntyre and Strauss 2014).The enhanced phenotypic plasticity ofplants forany functionaltraits may play a key role in their successful survival(Poorter et al. 2009;McIntyre and Strauss 2014).The result of this studymeans that the range of phenotypic plasticity of most functional traits of lanceolate leaves may be higher than those of heart-shaped leaves.The reason may be due to the fact that lanceolate leaves are the juvenile and heartshaped leaves are the adult leaf shape during the process of phylogenetic development of heterophyllous S.oblate. Meanwhile,plasticity index of leaf thickness and leaf moisture of sun trees was markedly higher than that of shade trees but opposite for petiole diameter,single leaf wet and dry weight,and SLA.We think that the higher range of phenotypic plasticity of leaf thickness and leaf moisture may help to obtain a more efficient control of water loss and nutrient deprivation in high-light environments and the lower range of phenotypic plasticity of single leaf wet and dry weight,and SLA may gain an advantage in increasing resource(especially light)capture and use efficiency in low-light environments(Burns and Beaumont 2009;McIntyre and Strauss 2014;Yang et al. 2014).The range of the relative distance plasticity index of SLA for different light intensities was obviously higher than that for different leaf-shape environments.This means that SLA may play an important role in resource (especially light)capture and use efficiency under different light intensities.

Generally,leaves with higher SLAs,which could invest less biomass into leaf construction in order to achieve a high resource acquisitive and use efficiency,show lower leaf thickness,and single-leaf wet and dry weight but higher leaf size and leaf moisture(Poorter et al.2009; McIntyre and Strauss 2014;Pietsch etal.2014;Yang etal. 2014).We found that SLA was positively correlated with leaf moisture butnegatively correlated with leaf thickness and single-leaf dry weight.Unfortunately,SLA and leaf size(leaf length and leaf width as the characterization)did not show a significant relationship.Empirical studies also achieve conflicting results,with observed correlations between leaf size and SLA thatare positive(Ackerly etal. 2002;Burns and Beaumont 2009),negative(Milla and Reich 2007;Niklas et al.2007),unrelated(Wright et al. 2007),or variable amongst habitats(Pickup et al.2005). Whatthis suggests is thatthere is species specificity forthe relationship among leaf functional traits.Consequently, results obtained in this study are only partly consistentwith the third hypothesis.

Previous studies founded thatleaf size and SLA decline along gradients of decreasing moisture(Fonseca et al. 2000;Ackerly et al.2002).Thus,we suppose that soil moisture is positively correlated with leaf size and SLA, butnotexactly the same as we found an inconsistentresult, i.e.,soilmoisture was only significantcorrelated with SLA but not leaf size.The positive relationship between SLA and soilmoisture may be due to the factthatplants which growth in the more humid soilsubsystems have a relatively high growth rate and lead to a decrease in the amount of biomass invested in leaf construction and then induced a high SLA(Fonseca et al.2000;Ackerly et al.2002).This paper also confirmed this point,that soil moisture in a shade environmentwas significantly higher than thatin sun environment and the SLA of shade trees was also significantly higher than that sun trees.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to gain insights into the differences in leaf functional traits of the heterophyllous plant S.oblata under different light intensities.Results showed that petiole diameter,leaf length,leaf thickness, the ratio of leaf length to petiole length,and leaf-shape index of heart-shaped leaves were significantly lower than those of lanceolate leaves but opposite for petiole length, leaf width,and single-leaf wet and dry weight.However, there was no significant difference in SLA between lanceolate and heart-shaped leaves.Thus,the difference in the investment per unit of light-capture surface deployed between lanceolate and heart-shaped leaves may be not obvious.Leaf thickness and single-leaf dry weight of sun trees were higherthan those ofshade trees butthe opposite for petiole length,leaf moisture,and SLA.Therefore,the material investment per unit area and per lamina of shade trees was significantly lower than that of sun trees to enhance light capture and use efficiency in low-light environments.The plasticity index of petiole diameter, petiole length,leaf width,leaf thickness,the ratio of leaf length to petiole length,single-leafwetand dry weight,and leaf moisture of lanceolate leaves were obviously higher than those of heart-shaped leaves but opposite for SLA. Thus,the phenotypic plasticity of mostfunctionaltraits of lanceolate leaves was higher than those of heart-shaped leaves.This may be due to the fact that lanceolate leaves are the juvenile and heart-shaped leaves are the adult leaf shape during the process of phylogenetic development of heterophyllous S.oblate.

The plasticity index of leaf thickness and leaf moisture ofsun trees were obviously higherthan those ofshade trees but opposite for petiole diameter,single-leaf wet and dry weight,and SLA.The higherrange ofphenotypic plasticity of leaf thickness and leaf moisture may be beneficial to obtain a more efficient control of water loss and nutrient deprivation in high-lightenvironments,and the lower range of phenotypic plasticity of single-leaf wet and dry weight, and SLA may gain an advantage in order to increase resource(especially light)capture and use efficiency in low-light environments.All in all,the successfully ecologicalstrategy ofplants is to find an optimalmode for the trade-off between various functional traits to obtain moreliving resources and achieve greater fitness advantages in the survival environment.

AcknowledgmentsWe are grateful to the anonymous reviewer for insightful and constructive comments that improved this manuscript greatly.

Ackerly DD,Knight CA,Weiss SB,Barton K,Starmer KP(2002) Leaf size,specific leaf area and microhabitat distribution of chaparralwoody plants,contrasting patterns in species leveland community level analyses.Oecologia 130:449–457

Battie-Laclau P,Laclau J-P,Beri C,Mietton L,Muniz MRA, Arenque BC,De Cassia Piccolo M,Jordan-Meille L,Bouillet J-P,Nouvellon Y(2014)Photosynthetic and anatomical responses of Eucalyptus grandis leaves to potassium and sodium supply in a field experiment.Plant Cell Environ 37:70–81

Burns KC,Beaumont S(2009)Scale-dependenttraitcorrelations in a temperate tree community.Austral Ecol 34:670–677

Campitelli BE,Stinchcombe JR(2013)Naturalselection maintains a single-locus leaf shape cline in Ivyleaf morning glory,Ipomoea hederacea.Mol Ecol 22:552–564

Chen LY,Tiu CJ,Peng SL,Siemann E(2013)Conspecific plasticity and invasion:invasive populations of Chinese tallow(Triadica sebifera)have performance advantage over native populations only in low soil salinity.PLoS ONE 8:e74961

Fonseca CR,Overton JM,Collins B,Westoby M(2000)Shifts in trait-combinations along rainfall and phosphorous gradients. J Ecol 88:964–977

Jeong N,Moon J,Kim H,Kim C,Jeong S(2011)Fine genetic mapping of the genomic region controlling leaflet shape and number of seeds per pod in the soybean.Theor Appl Genet 122:865–874

Kardel F,Wuyts K,Babanezhad M,Vitharana UWA,Wuytack T, Potters G,Samson R(2010)Assessing urban habitat quality based on specific leaf area and stomatal characteristics of Plantago lanceolata L.Environ Pollut 158:788–794

Lamarque LJ,Porte´AJ,Eymeric C,Lasnier J-B,Lortie CJ,Delzon S (2013)A test for pre-adapted phenotypic plasticity in the invasive tree Acer negundo L.PLoS ONE 8:e74239

Leigh A,Zwieniecki MA,Rockwell FE,Boyce CK,Nicotra AB, Holbrook NM(2011)Structural and hydraulic correlates of heterophylly in Ginkgo biloba.New Phytol 189:459–470

Liu FD,Yang WJ,Wang ZS,Xu Z,Liu H,Zhang M,Liu YH,An SQ, Sun SC(2010)Plant size effects on the relationships among specific leaf area,leaf nutrient content,and photosynthetic capacity in tropical woody species.Acta Oecol 36:149–159

McIntyre PJ,Strauss SY(2014)Phenotypic and transgenerational plasticity promote local adaptation to sun and shade environments.Ecol Evol 28:229–246

Mediavilla S,Escudero A(2009)Ontogenetic changes in leaf phenology of two co-occurring mediterranean oaks differing in leaf life span.Ecol Res 24:1083–1090

Meng FQ,Cao R,Yang DM,Niklas KJ,Sun SC(2014)Trade-offs between lightinterception and leafwatershedding:a comparison of shade-and sun-adapted species in a subtropical rainforest. Oecologia 174:13–22

Milla R,Reich PB(2007)The scaling of leaf area and mass:the cost of lightinterception increases with leafsize.Proc R Soc Lond B 274:2109–2114

Momokawa N,Kadono Y,Kudoh H(2011)Effects oflightquality on leafmorphogenesis ofa heterophyllous amphibious plant,Rotala hippuris.Ann Bot 108:1299–1306

Niinemets U¨,Sack L(2006)Structural determinants of leaf lightharvesting capacity and photosynthetic potential.Prog Bot 67:386–419

Niklas KJ,Cobb ED,Niinemets U,Reich PB,Sellin A,Shipley B, Wright IJ(2007)‘‘Diminishing returns’’in the scaling of functionalleaf traits across and within species groups.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:8891–8896

Pardos M,Calama R,Climent J(2009)Difference in cuticular transpiration and sclerophylly in juvenile and adult pine needles relates to the species-specific rates of development.Trees 23:501–508

Pearcy RW,Muraoka H,Valladares F(2005)Crown architecture in sun and shade environments:assessing function and trade-offs with a three-dimensional simulation model.New Phytol 166:791–800

Pickup M,Westoby M,Basden A(2005)Dry mass costs ofdeploying leaf area in relation to leaf size.Funct Ecol 19:88–97

Pietsch KA,Ogle K,Cornelissen JHC,Cornwell WK,Bo¨nisch G, Craine JM,Jackson BG,Kattge J,Peltzer DA,Penuelas J,Reich PB,Wardle DA,Weedon JT,Wright IJ,Zanne AE,Wirth C (2014)Global relationship of wood and leaf litter decomposability:the role of functional traits within and across plant organs.Glob Ecol Biogeogr 23:1046–1057

Poorter H,Niinemets U,Poorter L,Wright IJ,Villar R(2009)Causes and consequences of variation in leaf mass per area(LMA):a meta-analysis.New Phytol 182:565–588

Rozendaal DMA,Hurtado VH,Poorter L(2006)Plasticity in leaf traits of38 tropicaltree species in response to light;relationships with light demand and adult stature.Funct Ecol 20:207–216

Scheepens JF,Frei ES,Sto¨cklin J(2010)Genotypic and environmental variation in specific leaf area in a widespread Alpine plant after transplantation to different altitudes.Oecologia 164:141–150

Sun SC,Jin DM,Shi PL(2006)The leaf size-twig size spectrum of temperate woody species along an altitudinal gradient:an invariant allometric scaling relationship.Ann Bot97:97–107

Tanaka-Oda A,Kenzo T,Kashimura S,Ninomiya I,Wang LH, Yoshikawa K,Fukuda K(2010)Physiological and morphologicaldifferences in the heterophylly of Sabina vulgaris Ant.in the semi-arid environmentof Mu Us Desert,Inner Mongolia,China. J Arid Environ 74:43–48

Valladares F,Sanchez-Gomez D,Zavala MA(2006)Quantitative estimation ofphenotypic plasticity:bridging the gap between the evolutionary concept and its ecological applications.J Ecol 94:1103–1116

Wang Z,Zhang L(2012)Leafshape alters the coefficients ofleafarea estimation models for Saussurea stoliczkai in central Tibet. Photosynthetica 50:337–342

Wright IJ,Ackerly DD,Bongers F,Harms KE,Ibarra-Manriquez G, Martinez-Ramos M,Mazer SJ,Muller-Landau HC,Paz H, Pitman NCA,Poorter L,Silman MR,Vriesendorp CF,Webb CO,Westoby M,Wright SJ(2007)Relationships among ecologically-important dimensions of plant trait variation in seven neotropical forests.Ann Bot 99:1003–1015

Yang SJ,Sun M,Zhang YJ,Cochard H,Cao KF(2014)Strong leaf morphological,anatomical,and physiological responses of a subtropical woody bamboo(Sinarundinaria nitida)to contrasting light environments.Plant Ecol 215:97–109

3 December 2014/Accepted:7 April 2015/Published online:7 July 2015

©Northeast Forestry University and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015

Project funding:This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(31300343,31170386);NaturalScience Foundation of Jiangsu Province,China(BK20130500);Universities Natural Science Research Project of Jiangsu Province,China (13KJB610002);Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center of Technology and Materialof Water Treatment;Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions(PAPD);and Research Foundation for Advanced Talents,Jiangsu University(12JDG086).

The online version is available at http://www.springerlink.com

Corresponding editor:Hu Yanbo

✉Congyan Wang liuyuexue623@163.com

✉Daolin Du ddl@ujs.edu.cn

1School of the Environment and Safety Engineering,Institute of Environment and Ecology,Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang 212013,People’s Republic of China

2Key Laboratory of Modern Agricultural Equipment and Technology,Ministry of Education and Jiangsu Province, Jiangsu University,Zhenjiang 212013, People’s Republic of China

Journal of Forestry Research2015年3期

Journal of Forestry Research2015年3期

- Journal of Forestry Research的其它文章

- Management of pests and diseases of tropical sericultural plants by using plant-derived products:a review

- Gamma generalized linear model to investigate the effects of climate variables on the area burned by forest fire in northeast China

- Diversity,abundance,and structure of tree communities in the Uluguru forests in the Morogoro region,Tanzania

- Brazilian savanna re-establishment in a monoculture forest: diversity and environmental relations of native regenerating understory in Pinus caribaea Morelet.stands

- Carbon storage and sequestration rate assessment and allometric model development in young teak plantations of tropical moist deciduous forest,India

- Use of infrared thermal imaging to diagnose health of Ammopiptanthus mongolicus in northwestern China