大气可吸入性颗粒物暴露与儿童哮喘显著关联:基于22篇观察性研究的Meta分析

张娟娟 汪东海 代继宏

大气可吸入性颗粒物暴露与儿童哮喘显著关联:基于22篇观察性研究的Meta分析

张娟娟1汪东海1代继宏2

目的 定量分析大气可吸入性颗粒物(PM2.5,PM10)暴露对儿童哮喘发病风险的影响。方法 计算机检索PubMed、EMBASE、Cochrane图书馆、Ovid、中国生物医学文献数据库、中国知网和万方数据库,检索时间均为建库至2014年11月,同时手工检索相关杂志,纳入可吸入性颗粒物暴露与儿童哮喘关联的观察性研究文献。采用NOS和AHRQ量表进行文献偏倚评价。以可吸入性颗粒物浓度每升高10 μg·m-3与儿童哮喘发病风险关联强度的OR及其95%CI作为效应量,按急性效应和慢性效应分别行Meta分析,进一步按PM2.5和PM10行亚组分析。采用RevMan 5.3和Stata 12.0软件分别行异质性分析及发表偏倚检验,根据异质性分析结果采用相应的效应模型合并效应值。结果 31篇文献进入Meta分析,队列研究10篇,横断面研究12篇,病例交叉研究8篇,时间序列研究2篇。①22篇文献报道了可吸入性颗粒物对儿童哮喘发病风险的慢性效应,文献间具异质性,随机效应模型的Meta分析结果显示,合并OR=1.10(95%CI:1.03~1.17),即大气PM2.5或PM10浓度每上升10 μg·m-3,儿童哮喘的发病风险升高10%,亚组分析显示,PM2.5和PM10的合并OR值分别为1.08(95%CI:1.02~1.15)和1.10(95%CI:1.01~1.20)。②9篇文献报道了可吸入性颗粒物对儿童哮喘发病风险的急性效应,文献间具异质性,随机效应模型的Meta分析结果显示,合并OR=1.05(95%CI:1.02~1.08),即大气PM2.5或PM10浓度每上升10 μg·m-3,儿童哮喘的发病风险升高5%;亚组分析显示,PM2.5和PM10的合并OR值分别为1.06(95%CI:1.02~1.10)和1.05(95%CI:1.02~1.08)。③Egger直线回归法发表偏倚检验显示,急性效应不存在发表偏倚,慢性效应存在发表偏倚。结论 PM2.5和PM10水平与儿童哮喘发病风险的急性和慢性效应存在显著关联。

可吸入性颗粒物; 儿童; 哮喘; 系统评价; Meta分析

近几十年内儿童哮喘的患病率呈明显的上升趋势[1]。有研究表明[2],哮喘是在遗传易感性的基础上与环境因素相互作用而发生的疾病,主要归纳为感染因素、理化因素及致敏因素。与此同时,随着人们对环境污染与自身健康关系的日益关注,大气污染特别是大气颗粒物污染已成为近年来的热点问题。国内外流行病学研究和毒理学研究显示[3],大气可吸入颗粒物暴露与人群健康效应相关,主要包括呼吸系统和心脑血管疾病发病率和死亡率升高等。儿童处于不断生长中,单位体重呼吸量高于成人,且呼吸系统和免疫系统发育尚不完善,使其更易遭受空气污染侵害[4]。目前关于大气可吸入颗粒物对儿童哮喘发病风险的影响已有较多的研究,如采用队列和横断面设计分析可吸入颗粒物对儿童哮喘发病风险的慢性效应[5],即长期可吸入颗粒物暴露对儿童哮喘发病的影响;以时间序列(time-series)和病例交叉(case-crossover)设计观察大气颗粒物短期波动对儿童哮喘发病风险的影响;但已发表的研究结论不一致。Gasana等[6]在2012年发表的Meta分析探讨了可吸入颗粒物暴露与儿童哮喘的关联性,但仅从慢性效应角度分析,且未纳入中文发表的文献,因此有必要对该Meta进行更新和进一步分析,明确可吸入颗粒物暴露对儿童哮喘患病风险的影响。

1 方法

1.1 文献纳入标准 ①观察性研究(队列、病例交叉、横断面和时间序列研究);②报道了大气可吸入颗粒物PM2.5和PM10水平;③研究对象为儿童,且文献中描述了哮喘的诊断标准;④文献中报道了本文结局指标数据,且提供了OR值及其95%CI;⑤重复发表的文献,取样本量较大的研究,同一研究不同观察时间发表的文献,取观察时间最长的文献;⑥语种限定为中文和英文。

1.2 文献排除标准 研究人群包括成人和儿童,但无法单独提取儿童数据的文献。

1.3 结局指标 报道的儿童哮喘患病率、发病率和就诊率,可直接表示或间接转化为可吸入性颗粒物浓度每升高10 μg·m-3,与儿童哮喘发病风险关联强度的OR值及其95%CI。

1.4 文献检索策略 计算机检索PubMed、EMBASE、Cochrane图书馆、Ovid、中国生物医学文献数据库(CBM)、中国知网和万方数据库,检索时间均为建库至2014年11月27日。回溯纳入文献的参考文献。以PubMed数据库为例的检索式为((Child* OR Pediatrics [MeSH] OR Child [MeSH]) AND (Asthma [MeSH])) AND (Air Pollut* OR Air quality OR PM2.5 OR PM10 OR ultrafine particles OR fine particulate matter OR particles OR "Air pollutants" [MeSH]) AND Risk;以CBM为例的检索式为(儿童哮喘 OR 儿童喘息) AND (空气污染 OR 颗粒物 OR PM10 OR PM2.5)。

1.5 文献筛选、资料提取和偏倚风险评估 由本文作者张娟娟和汪东海分别独立完成,如遇分歧讨论决定。

1.5.1 文献筛选 剔除重复发表、与研究目的不符和明显不满足纳入标准的文献,初筛后的文献获取全文再评估是否符合纳入标准。

1.5.2 资料提取 采用资料登记表提取纳入文献的数据,包括文献题目、发表年份、研究设计、受试对象、人口学特征、样本量和结局指标等。

1.5.3 偏倚风险评价 纳入的队列和病例交叉研究采用NOS量表(the Newcastle Ottawa Scale)行偏倚风险评价,包括入组标准符合性(4项内容)、研究方法可比性(2项内容)和资料完整性(3项内容),满足1项内容记1分,总分为9分。横断面研究采用AHRQ量表行偏倚风险评估,推荐的标准包括11个条目,分别用“是”、“否”、“不清楚”及“不适用”作答。目前无时间序列研究的质量评估工具。

1.6 统计学方法 采用RevMan 5.3和Stata 12.0软件进行Meta分析,效应量以OR及其95%CI表示。采用χ2检验行统计学异质性分析,P≤0.1为研究间存在显著异质性;采用I2对异质性进行定量,I2≤50%为低中度异质性,采用固定效应模型分析;I2>50%为高度异质性,采用随机效应模型分析。对无法合并效应量的文献采用描述性分析,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果

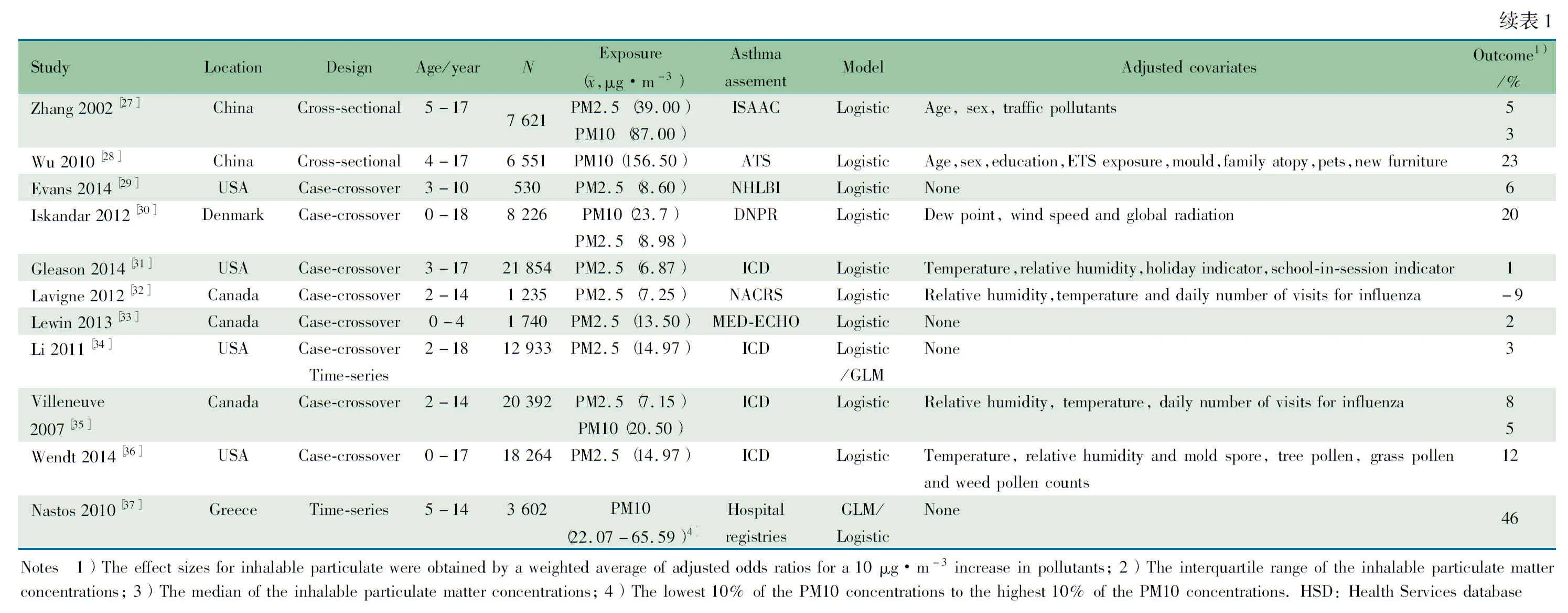

2.1 纳入文献基本情况 共检索到7 105篇文献(PubMed 805篇、EMBASE 950篇、Cochrane图书馆63篇、Ovid 5 159篇、CBM 20篇、中国知网53篇、万方数据库53篇及参考文献回溯7篇)。31篇文献符合本文纳入标准进入Meta分析(图1),其中队列研究10篇[7~16],横断面研究12篇[17~28],病例交叉研究8篇[29~36],时间序列研究2篇[34,37]。纳入文献的基本特征如表1所示。

图1 文献筛选流程图

Fig 1 Flow chart of article inclusion and exclusion process

2.2 文献偏倚评价结果 偏倚评价结果显示,10篇队列研究[7~16]暴露队列的代表性均充分,9篇文献[7~14,16]非暴露组与暴露组不是来自同一人群,10篇文献暴露因素的确定方法均可靠,确定研究起始时均无需观察的结局指标,暴露组和非暴露组间均具可比性,结局的测量方法均可靠,3篇文献[13,14,16]未设计恰当的随访时间,10篇文献均完成随访且失访率较低。3篇文献[13,14,16]评为7分,6篇文献[7~12]评为8分,文献[15]评为9分。

8篇病例交叉研究[29~36]病例的确定、病例的代表性和对照的选择均恰当,对照的确定均不恰当,5篇文献[30~32,35,36]组间可比性较好,8篇文献暴露因素的确定方法可靠、且采用相同的方法测量病例组和对照组的暴露因素,均描述了无应答率的数据。3篇文献[29,33,34]评为7分,5篇文献[30~32,35,36]评为8分。

12篇横断面研究[17~28]偏倚评价的11个条目中,条目4(如不是人群来源,研究对象是否连续)和条目11(如有随访,报告失访数据)不适用,故行9个条目的评价。12篇文献均明确数据的来源,文献[17]明确了纳入和排除标准,余11篇文献未提及;8篇文献[17,19,21~26]给出了鉴别患儿的时间阶段,均描述了研究的质量控制;3篇文献[17,20,25]描述了排除分析患儿的理由;10篇[17~25,28]文献描述了控制混杂因素的措施;均未报道缺失数据的处理;8篇文献[17,19,21~26]描述了应答率。

2.3 Meta分析结果

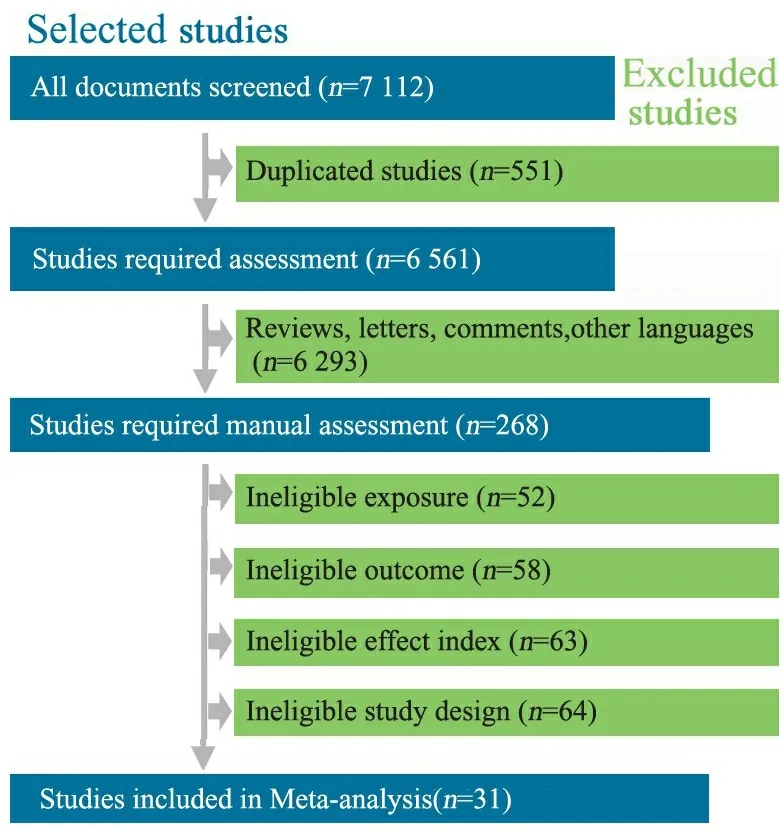

2.3.1 可吸入性颗粒物对儿童哮喘发病风险的慢性效应 22篇文献报道了可吸入性颗粒物对儿童哮喘的慢性效应。文献间具异质性(P<0.001,I2=72%),采用随机效应模型合并结果。Meta分析结果显示(图2),合并OR=1.10(95%CI:1.03~1.17,P=0.03),即大气PM2.5或PM10浓度每上升10 μg·m-3儿童哮喘的发病风险升高10%。

根据颗粒物的大小行亚组分析,报道PM2.5和哮喘关联性的文献间具同质性,采用固定效应模型分析,Meta分析结果显示,合并OR=1.08(95%CI:1.02~1.15,P=0.01);报道PM10和哮喘关联性的文献间具异质性(I2=82%),采用随机效应模型分析,合并OR=1.10(95%CI:1.01~1.20,P=0.02)。

图2 可吸入颗粒物对儿童哮喘慢性效应的Meta分析

Fig 2 Meta-analysis of chronic effects of inhaled particulate matter on asthma in children

2.3.2 可吸入性颗粒物对儿童哮喘发病风险的急性效应 9篇文献报道了可吸入性颗粒物暴露对儿童哮喘的急性效应,文献间具显著统计学异质性(P<0.1,I2=63%),采用随机效应模型合并,Meta分析结果显示(图3),合并OR=1.05(95%CI:1.02~1.08,P=0.003),即大气PM2.5或PM10浓度每上升10 μg·m-3儿童哮喘的发病风险升高5%。

根据颗粒物的大小行亚组分析,报道PM2.5和哮喘关联性的文献间具异质性(I2=70%),采用随机效应模型合并结果,合并OR=1.06(95%CI:1.02~1.10,P=0.004);报道PM10和哮喘关联性的文献间具同质性(I2=20%),采用固定效应模型分析,Meta分析结果显示,合并OR=1.05(95%CI:1.02~1.08,P=0.001)。

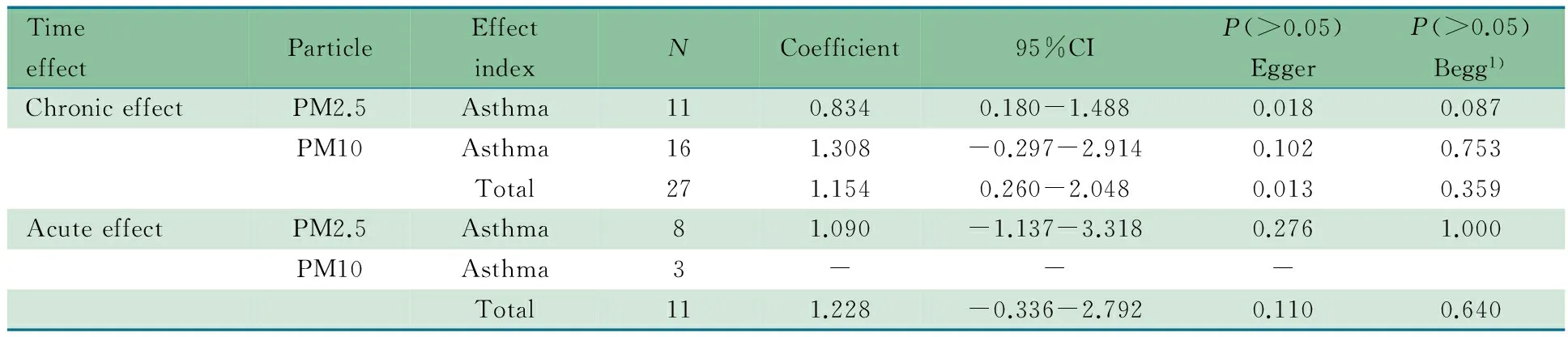

2.4 发表偏倚 分别采用Begg 秩相关法和Egger直线回归法行发表偏倚检验。用Begg秩相关法结果显示(表3), 纳入文献连续性校正,各文献P值>0.05;采用Egger直线回归法结果显示(表3),慢性效应中存在发表偏倚(P=0.013),与Begg 秩相关法结果不一致。通常Egger检验效能较Begg稍高[38],故认为报告慢性效应文献存在发表偏倚,报告急性效应文献不存在发表偏倚。

图3 可吸入性颗粒物对儿童哮喘急性效应的Meta分析

表3 发表偏倚的Egger和Begg直线回归法检验结果

Notes 1) continuity corrected

3 讨论

本文Meta分析纳入的31篇文献均为观察性研究,其中队列研究10项,是探讨病因学较好的研究设计类型,纳入文献的总体样本量较大。本文纳入的队列研究和病例交叉研究采用NOS评分评估偏倚风险,12/18篇文献≥8分,纳入的横断面研究采用AHQR量表评价,其中9个条目的符合率均较高,进入本文分析的文献质量为高。急性和慢性效应均存在剂量效应关系。本文纳入的文献间存在一定的临床异质性,如可吸入性颗粒物大小,不同地区及不同年龄段等均存在差异,故进一步对颗粒物大小进行亚组分析,但仍不能完全消除文献间的异质性,同时慢性效应文献存在发表偏倚,结合GRADE证据质量评价工具,可吸入颗粒物对儿童哮喘发病风险急性和慢性效应的证据质量均为低。

多项研究结果表明,可吸入性颗粒物是引起和加重支气管哮喘尤其是过敏性哮喘的重要危险因素,其作用主要是免疫-炎症机制,主要为两方面[39]:①可吸入性颗粒物本身可通过引起Th1/Th2和细胞因子的失衡而诱发哮喘;②可吸入性颗粒物表面吸附一定的过敏原,可以强化和放大此炎症反应。本文Meta分析结果显示,可吸入性颗粒物(PM2.5、PM10)不论从急性抑或慢性效应均会增加儿童哮喘患病风险,其中慢性效应的关联强度更高。关于颗粒物大小对儿童哮喘患病风险的影响,急性效应时PM2.5更为明显,在慢性效应时PM10更为明显。Gasana等[6]在2012年从队列和横断面研究角度分析室外空气污染物与儿童哮喘关联性的Meta分析显示,PM2.5和PM10从慢性效应可增加哮喘患病风险。中国2015年发表的基于病例交叉和时间序列研究的Meta分析显示,可吸入颗粒物从急性效应可增加儿童哮喘的风险[40]。与本文Meta分析结果一致。

结论:本文Meta分析结果提示,PM2.5和PM10水平与儿童哮喘发病风险的急性效应和慢性效应存在显著关联。

[1]Anandan C, Nurmatov U, van Schayck OC, et al. Is the prevalence of asthma declining? Systematic review of epidemiological studies. Allergy, 2010, 65(2): 152-167

[2]蔡婧. 城市个体黑碳暴露特征与儿童呼吸道健康效应关系研究. 华东理工大学, 2013

[3]Atkinson RW, Kang S, Anderson HR, et al. Epidemiological time series studies of PM2.5 and daily mortality and hospital admissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax, 2014, 69(7): 660-665

[4]Ferrante G, Antona R, Malizia V, et al. Asthma and air pollution. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 2014, 40(S1): A75

[5]Hong CJ(洪传洁), Kan HD, Chen BH. 城市大气污染健康危险度评价的方法第五讲大气污染对城市居民健康危害的定量评估(续五). J Environ Health(环境与健康杂志), 2005, 22(1): 62-64

[6]Gasana J, Dillikar D, Mendy A, et al. Motor vehicle air pollution and asthma in children: a meta-analysis. Environ Res, 2012, 117: 36-45

[7]Brauer M, Hoek G, Van Vliet P, et al. Air pollution from traffic and the development of respiratory infections and asthmatic and allergic symptoms in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2002, 166(8): 1092-1098

[8]Brauer M, Hoek G, Smit HA, et al. Air pollution and development of asthma, allergy and infections in a birth cohort. Eur Respir J, 2007, 29(5): 879-888

[9]Clark NA, Demers PA, Karr CJ, et al. Effect of early life exposure to air pollution on development of childhood asthma. Environ Health Perspect, 2010, 118(2): 284-290

[10]Gehring U, Cyrys J, Sedlmeir G, et al. Traffic-related air pollution and respiratory health during the first 2 yrs of life. Eur Respir J, 2002, 19(4): 690-698

[11]Gehring U, Wijga AH, Brauer M, et al. Traffic-related air pollution and the development of asthma and allergies during the first 8 years of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2010, 181(6): 596-603

[12]Gruzieva O, Bergstrom A, Hulchiy O, et al. Exposure to air pollution from traffic and childhood asthma until 12 years of age. Epidemiology, 2013, 24(1): 54-61

[13]Morgenstern V, Zutavern A, Cyrys J, et al. Respiratory health and individual estimated exposure to traffic-related air pollutants in a cohort of young children. Occup Environ Med, 2007, 64(1): 8-16

[14]Morgenstern V, Zutavern A, Cyrys J, et al. Atopic diseases, allergic sensitization, and exposure to traffic-related air pollution in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2008, 177(12): 1331-1337

[15]Peters JM, Avol E, Navidi W, et al. A study of twelve Southern California communities with differing levels and types of air pollution. I. Prevalence of respiratory morbidity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 1999, 159(3): 760-767

[16]Shima M, Nitta Y, Ando M, et al. Effects of air pollution on the prevalence and incidence of asthma in children. Arch Environ Health, 2002, 57(6): 529-535

[17]Akinbami LJ, Lynch CD, Parker JD, et al. The association between childhood asthma prevalence and monitored air pollutants in metropolitan areas, United States, 2001-2004. Environ Res, 2010, 110(3): 294-301

[18]Braun-Fahrländer C, Vuille JC, Sennhauser FH, et al. Respiratory health and long-term exposure to air pollutants in Swiss schoolchildren. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 1997, 155(3): 1042-1049

[19]Dockery DW, Cunningham J, Damokosh AI, et al. Health effects of acid aerosols on North American children: respiratory symptoms. Environ Health Perspect, 1996, 104(5): 500-505

[20]Hwang BF, Lee YL, Lin YC, et al. Traffic related air pollution as a determinant of asthma among Taiwanese school children. Thorax, 2005, 60(6): 467-473

[21]Kim JJ, Smorodinsky S, Lipsett M, et al. Traffic-related air pollution near busy roads: the East Bay Children's Respiratory Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2004, 170(5): 520-526

[22]Liu MM, Wang D, Zhao Y, et al. Effects of outdoor and indoor air pollution on respiratory health of Chinese children from 50 kindergartens. J Epidemiol, 2013, 23(4): 280-287

[23]Liu F, Zhao Y, Liu YQ, et al. Asthma and asthma related symptoms in 23,326 Chinese children in relation to indoor and outdoor environmental factors: The Seven Northeastern Cities (SNEC) Study. Sci Total Environ, 2014, 497: 10-17

[24]Penard-Morand C, Charpin D, Raherison C, et al. Long-term exposure to background air pollution related to respiratory and allergic health in schoolchildren. Clin Exp Allergy, 2005, 35(10): 1279-1287

[25]Penard-Morand C, Raherison C, Charpin D, et al. Long-term exposure to close-proximity air pollution and asthma and allergies in urban children. Eur Respir J, 2010, 36(1): 33-40

[26]Portnov BA, Reiser B, Karkabi K, et al. High prevalence of childhood asthma in Northern Israel is linked to air pollution by particulate matter: evidence from GIS analysis and Bayesian Model Averaging. Int J Environ Health Res, 2012, 22(3): 249-269

[27]Zhang JJ, Hu W, Wei F, et al. Children's respiratory morbidity prevalence in relation to air pollution in four Chinese cities. Environ Health Perspect, 2002, 110(9): 961-967

[28]Wu JG(吴金贵), Tang CX, Zhuang ZJ, et al. effect of indoor air pollution related to traffic and fuel gas using for cooking on respiratory diseases in children and teenagers in urban area of Shanghai. J Environ Health(环境与健康杂志), 2010, 27(3): 244-247

[29]Evans KA, Halterman JS, Hopke PK, et al. Increased ultrafine particles and carbon monoxide concentrations are associated with asthma exacerbation among urban children. Environ Res, 2014, 129: 11-19

[30]Iskandar A, Andersen ZJ, Bonnelykke K, et al. Coarse and fine particles but not ultrafine particles in urban air trigger hospital admission for asthma in children. Thorax, 2012, 67(3): 252-257

[31]Gleason JA, Bielory L, Fagliano JA. Associations between ozone, PM2.5, and four pollen types on emergency department pediatric asthma events during the warm season in New Jersey: a case-crossover study. Environ Res, 2014, 132: 421-429

[32]Lavigne E, Villeneuve PJ, Cakmak S. Air pollution and emergency department visits for asthma in Windsor, Canada. Can J Public Health, 2012, 103(1): 4-8

[33]Lewin A, Buteau S, Brand A, et al. Short-term risk of hospitalization for asthma or bronchiolitis in children living near an aluminum smelter. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol, 2013, 23(5): 474-480

[34]Li S, Batterman S, Wasilevich E, et al. Association of daily asthma emergency department visits and hospital admissions with ambient air pollutants among the pediatric Medicaid population in Detroit: time-series and time-stratified case-crossover analyses with threshold effects. Environ Res, 2011, 111(8): 1137-1147

[35]Villeneuve PJ, Chen L, Rowe BH, et al. Outdoor air pollution and emergency department visits for asthma among children and adults: a case-crossover study in northern Alberta, Canada. Environ Health, 2007, 6: 40

[36]Wendt JK, Symanski E, Stock TH, et al. Association of short-term increases in ambient air pollution and timing of initial asthma diagnosis among Medicaid-enrolled children in a metropolitan area. Environ Res, 2014, 131: 50-58

[37]Nastos PT, Paliatsos AG, Anthracopoulos MB, et al. Outdoor particulate matter and childhood asthma admissions in Athens, Greece: a time-series study. Environ Health, 2010, 9: 45

[38]Pelletier JP, Jovanovic D, Fernandes JC, et al. Reduced progression of experimental osteoarthritis in vivo by selective inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Arthritis Rheum, 1998, 41(7): 1275-1286

[39]Liu QQ(刘青青), Chen L.Impact of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) on asthma among children: a review of recent studies. J Environ Health(环境与健康杂志), 2012, 29(7): 665-668

[40]Ding L(丁玲), Zhu HJ, Peng DH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5)and asthma hospital admissions in children. Chin J Pediatr(中华儿科杂志), 2015, 53(2): 129-135

(本文编辑:丁俊杰)

Association between inhalable particulate matter and asthma in children: a meta-analysis based on 22 observational studies

ZHANGJuan-juan1,WANGDong-hai1,DAIJi-hong2

(1KeyLaboratoryofDevelopmentalDiseasesinChildhoodofMinistryofEducation,Chongqing400014; 2CenterofRespiratoryDisordersofChildren'sHospital,ChongqingMedicalUniversity,Chongqing400014,China)

DAI Ji-hong,E-mail:danieljh@163.com

ObjectiveTo quantitatively estimate the association between particulate matter with asthma in children.MethodsPubMed, EMBASE, Ovid, Cochrane Library, CBM, CNKI and Wanfang database were searched up to November 2014, and additional studies were manual screened. Observational studies assessing the association between inhalable particulate matter(PM2.5,PM10) and risk of childhood asthma were included. The quality of the literatures was evaluated by the Newcastle Ottawa Scale and AHRQ. The adjusted effect sizes and corresponding 95% CI for asthma attack corresponding to a 10 μg·m-3increment in exposure to inhalable particulate matter were investigated and conducted to identify the acute and chronic effects. Furthermore, subgroup analysis was conducted by the sizes of inhalable particulate matter. RevMan 5.3 and Stata 12.0 software were used to perform heterogeneity analysis and the test of publication bias. The pooled effect was conducted on the basis of effect model.Results Thirty-one studies were identified, including 10 cohort studies, 12 cross-sectional studies, 8 case-crossover studies and 2 time-series studies. ①Twenty-two literatures reported the chronic effects of exposure to inhalable particles on childhood asthma, which exhibited heterogeneity (P<0.001,I2=72%). The pooled effect sizes of odds ratio based on random effect model were 1.10 (95%CI: 1.03-1.17), which indicated that the incidence of pediatric asthma increased 10% by a weighted average of adjusted OR for a 10 μg·m-3increase in inhalable particles. In subgroup analysis, the combined odds ratios of PM2.5 and PM10 were 1.08 (95%CI: 1.02-1.15) and 1.0 (95%CI: 1.01-1.20) respectively. ② Nine literatures reported the acute effects of exposure to inhalable particles on childhood asthma. The pooled effect sizes were 1.05 (95%CI: 1.02-1.08), which indicated that the incidence of pediatric asthma increased 5% by a weighted average of for a 10 μg·m-3increment of adjusted OR in inhalable particles. In subgroup analysis, the combined OR of PM2.5 and PM10 corresponded to 1.06 (95%CI: 1.02-1.10) and 1.05 (95%CI: 1.02-1.08) respectively. ③The test of publication bias using Egger's regression method showed the absence of publication bias in reports of acute effects, and the presence in reports of chronic effects.ConclusionThere is significant association between the level of PM 2.5, PM 10 and the risks of acute and chronic childhood asthma.

Inhalable particulate matter; Children; Asthma; Systematic review; Meta-analysis

10.3969/j.issn.1673-5501.2015.05.004

1 重庆医科大学附属儿童医院儿童发育与疾病教育部重点实验室 重庆,400014;2 重庆医科大学附属儿童医院呼吸中心 重庆,400014

代继宏,E-mail:danieljh@163.com

2015-07-30

2015-09-15)