Predicting Pressure Ulcer Risk with the Braden Q Scale in Chinese Pediatric Patients in ICU

Ye-Feng Lua, Yan Yangb, Yan Wanga, Lei-Qing Gaoa, Qing Qiua, Chen Lia, Jing Jina

a Department of Hepatic Surgery, Renji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200127, China b Nursing Department, Renji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai200127, China

Predicting Pressure Ulcer Risk with the Braden Q Scale in Chinese Pediatric Patients in ICU

Ye-Feng Lua, Yan Yangb*, Yan Wanga, Lei-Qing Gaoa, Qing Qiua, Chen Lia, Jing Jina

aDepartmentofHepaticSurgery,RenjiHospital,SchoolofMedicine,ShanghaiJiaoTongUniversity,Shanghai200127,ChinabNursingDepartment,RenjiHospital,SchoolofMedicine,ShanghaiJiaoTongUniversity,Shanghai200127,China

1. Introduction

Curley et al developed the Braden Q Scale based on the Braden Scale. The Braden Q Scale has been proven to be valid in American pediatric patients.1 However, no useful pressure ulcer risk assessment scale in China has been tested and published to date.

A pressure ulcer, or bedsore, is any lesion caused by unrelieved pressure that ultimately damages the underlying tissue.1 Although pressure ulcers can develop on any part of the skin surface, they are predominantly found on the skin covering the bony prominences of the sacrum and heels in adults.2-4 Pressure ulcer development is associated with several adverse consequences, including increased pain to the patient, extended hospital stays, elevated medical costs and an increased mortality rate.5

The mechanism of pediatric pressure ulcer formation is similar to the mechanism in adults, but the affected sites differ. Children under the age of three most often suffer from pressure ulcers on the heels, ears, and the occipital area. In fact, pediatric patients who cannot move are at the highest risk for pressure ulcers.6

Prevention of pressure ulcer formation has been of paramount importance to clinicians, and many countries use pressure ulcer incidence as an indicator to evaluate nursing quality.7 The incidence and prevalence of pediatric pressure ulcers varies across different populations. Baldwin reported that the occurrence rate of pediatric bedsores was 0.29%; however, the morbidity was 0.47%.8 Curley and her colleagues showed an occurrence rate of 24% in PICU patients.9 The incidence of pediatric pressure ulcers in Chinese patients was 17.56%.10 Over 100 different risk factors have been identified for the development of pressure ulcers.11 Given the high incidence of pressure ulcers in the pediatric patient population, an assessment scale that can evaluate the risk for pressure ulcers is both necessary and warranted.

The process of preventing pressure ulcer formation in patients is systematic and typically involves the implementation of a pressure ulcer risk assessment scale (RAS). Use of a pressure ulcer RAS is an integral part of intervention by nurses and improves nurse awareness of pressure ulcer prevention. The three most frequently used RAS scales are the Norton, Braden, and Waterlow scales. The Braden Q Scale, however, is the most often implemented in pediatric patient populations. Aside from the Braden Q scale, the Bedi, Garvin, Pickersgill, Cockett, Olding and Patterson and Pediatric Waterlow scales have also been improved to assess the risks of bedsores in children.12

In China, the implementation of RAS in pediatric patients has been poor, with only 33.3% of nurses using such assessment tools.13 Instead, nurses make assessments according to their own experience.

Quigley & Curley14 modified the adult Braden Scale so that it could be used in a pediatric population. The Braden Q Scale focuses on the special aspects of pediatrics, for example, the growing application of gastric tube feedings to fit the RAS to young patients.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Settings

This prospective cohort study was conducted in a 20-bed PICU located in Shanghai, China. The PICU is a free-standing facility affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University Children's Hospital. This study was reviewed and approved by the Clinical Investigation Committee of the hospital's Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Study population

The study population included 198 consecutive PICU patients bedridden for at least 24 hours. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects that participated in the study. Patients with pre-existing pressure ulcers were excluded from this study. Patients older than 21 postnatal days of age were included in the study because, at 3 weeks of age, the skin is considered mature even if an infant was prematurely born.15 Patients over the age of eight were excluded because the American Heart Association considers patients >8 years old to be adults in terms of medical treatment.16

2.3. Instruments

In addition to the Braden Q Scale, three other instruments were used for data collection. The Demographic Data Collection Tool was used to collect patients' personal information, such as sex, age, weight, etc. The Daily Patient Assessment and Intervention Tool was used to record patients' medical information, such as temperature, blood pressure, etc.

The Skin Assessment Tool17 drew every bony bulge and required that the evaluator indicate whether ulcers appear or not at each point. Pressure ulcers were staged according to the following American National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel18 recommendations: Stage Ⅰ. Nonblanchable erythema not resolving within 30 minutes of pressure relief, epidermis remains intact. Stage Ⅱ. Partial thickness loss of skin layers involving epidermis and possibly penetrating into but not through the dermis, may present as blister. Stage Ⅲ. Full-thickness tissue loss extending through the dermis to involve subcutaneous tissue. Stage Ⅳ. Deep-tissue destruction extending through subcutaneous tissue to fascia and may involve muscle layers, joints, and/or bone.

2.4. Protocol

Prior to data collection, the principal investigator trained the data collectors in the study procedures, scoring the Braden Q, and staging pressure ulcers. The original inquirer and information collectors gave the patients' score until the patients achieved a clear status on each subscale of the Braden Q Scale. After that, staff members graded ten patients separately, and they stopped when they achieved a similarity of 90% on Braden Q scores and when the differences within each subscale of the Braden Q Scale were no more than one point. Thereafter, the percent agreement between the data collectors was re-evaluated bimonthly.

Two nurses, blinded to the other assessments and scores, observed patients up to 3 times a week (Monday, Wednesday, and/or Friday) for 2 weeks, then once a week (Wednesday) until discharge from the PICU. Nurse I enrolled patients who met the inclusion criteria, completed the Demographic Data Collection Tool and the Daily Patient Assessment and Intervention Tool, then rated each patient using the Braden Q Scale. Nurse II completed a head-to-toe skin assessment using the Skin Assessment Tool. The initial skin assessment occurred within a few hours of enrollment. If a pressure ulcer was identified, the patient's nurse was notified so that treatment could be implemented and/or continued.

2.5. Data analysis

Parametric and nonparametric statistics were used to describe the patient sample. Pressure ulcer positive (PU+) subjects were compared to pressure ulcer negative (PU -) subjects using data obtained during the first observation because most pressure ulcers (64%) noted were present at this time. Diagnostic capacity parameters (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value) were computed according to the Braden Q scores.19 Sensitivity is the percentage of people who have the dysfunction of interest and a positive result on x test. Specificity is the percentage of people who do not have the dysfunction of interest and a negative result on x text. The positive predictive value (PPV) is the percentage of patients who have a positive result on x test and also have the dysfunction of interest. The negative predictive value (NPV) in the percentage of patients who have a negative x test result and do not have the dysfunction of interest.

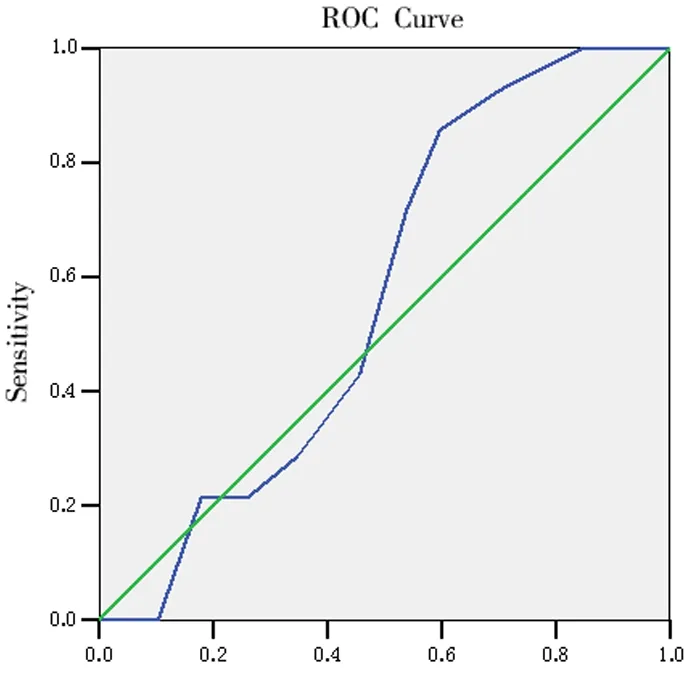

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis plotted sensitivity against 1-specificity over the range of Braden Q scores to confirm the critical value of the Braden Q Scale. As described by Bergstrom, Braden, Kemp and others,20 an ROC curve provides a visual representation of the tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity for a test with a range of values. Using the same scale on both axes, the sensitivity is plotted on the vertical axis against 1-specificity on the horizontal axis over a range of potential cutoff scores. The AUC is a commonly used summary measure for ROC curves, with higher AUC arising from more accurate tests. When the test has no diagnostic ability to predict the outcome, the AUC would equal 0.5.

The optimal cutoff point is usually identified in the region where the ROC curve changes direction-the inflection point. Because predicting patients at risk for pressure ulcers is more important than predicting patients not at risk, the optimal cutoff point was determined to provide high sensitivity and adequate specificity.

3. Results

This study enrolled 198 pediatric patients. On average, patients were 4 years of age and 63.1% male. The most common diagnoses were pulmonary disease (25.8%), heart disease (17.7%), and hematological disease(13.6%). Most patients (62.1%) were supported by mechanical ventilation, and most patients (52.0%) received sedation. The median PICU length of stay was 11 days; most patients were transferred to an inpatient pediatric unit.

A total of 14 patients developed pressure ulcers, an incidence of 7.1%. Stage I pressure ulcers were observed in 12 (6.1%) cases, and stage Ⅱ pressure ulcers in 2 (1.0%). The most common sites of pressure ulcers were the occipital area, sacral area and heel, and 3 pressure ulcers developed on these sites. There were 9 (64.3%) pressure ulcers present on the first observation. Table 1 indicates that the Braden Q Scale has an overall cumulative variance contribution rate of 69.599%.

There were no significant differences in the Braden Q scores between ulcer-positive and -negative patients (Table 2).

There were significant differences in the PH value between ulcer-positive and negative- patients, but no significant differences were found in other variables (Table 3).

Using Stage I + pressure ulcer data obtained during the first observation, a Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) curve plotting sensitivity and 1-specificity for each possible score of the Braden Q Scale was constructed (Fig.1). The AUC was 0.57, and the 95% confidence interval was 0.50-0.62. A cutoff score of 19 provided a high sensitivity and adequate specificity. At a score of 19, the sensitivity was 0.71 and the specificity was 0.53 (Table 4).

1-specificityFig.1. Braden Q Scale receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The ROC curve plots sensitivity and 1-specificity of each possible score of the Braden Q Scale.

The ROC curves were then constructed for each subscale of the Braden Q Scale, and the AUC of each item of the Braden Q Scale is 0.543-0.612.

4. Discussion

A study of a veteran with Spinal Cord Injury showed that diabetes and depression were risk factors for pressure ulcer formation,21 and it linked pressure with the diagnosis. The most common diagnosis in this study was pulmonary disease (25.8%), followed by heart disease and hematological disease. Pulmonary and heart disease affect patients' oxygenation and induce pressure ulcers, which are consistent with the mechanism of pressure ulcer. Because the sample size was small, the relationship between pressure ulcer and diagnosis needs to be proved by further studies.

The incidence and prevalence of different population differed greatly. Baldwin reported that the incidence in children is 0.29%, and the prevalence is 0.47%.8 Curley's study showed that the incidence of PICU patients is 24%;9 and the incidence of Chinese pediatric patients is 17.56%.10 In this study, there were 14 cases of pressure ulcers, and the incidence was 7.1%, which is less than the above-mentioned reports. However, the difference of the population seemed to explain the different incidence rates. Bergstrom's research also indicated the incidence differed with population.22

In the United States, a study involving 1 064 pediatric patients showed that the most common site of pediatric pressure ulcers was the occipital area (31%), followed by the sacral area (20%) and heel (19%)23, and McCord also reported the common site of pressure ulcers in infants was the occipital area, and sacral bone for children24 In this study, the most common sites of pressure ulcer were occipital area, sacral area and heel, and 3 pressure ulcers developed on these sites, which is in keeping with the reports described above. Pediatric pressure ulcers are different from those of adults because the most common site in adults is at the sacral area but the occipital area for children. The potential cause may be that children's brains are not mature, and the head-to-body ratio is different from that of adults. The results of this study indicate that we should pay more attention to pediatric pressure ulcers in clinical practice.

The main function of the pressure ulcer risk assessment scale (PURAS) is to systemically and accurately identify patients who may develop pressure ulcers and to guide nurses to carry out preventive interventions. Schoonhoven25 noted that most PURAS were developed based on research results and literature reviews, and the sensitivity and specificity of each scale varies widely. Balzer26 showed that the sensitivity and specificity of the Norton, Waterlow and Braden Scale were 0.79, 0.84, 0.84 and 0.76, 0.69, 0.62, respectively, illustrating the differences. However, among the 10 pediatric PURASs, only the Braden Q Scale, Glamorgan Scale and Neonatal Skin Risk Assessment Scale were tested for sensitivity, with values of 0.88, 0.98 and 0.83. In this study, when the value was 14-20, the sensitivity was 0.21-0.79, the specificity was 0.29-0.82, the cutoff score was 19, and the sensitivity and specificity were 0.71 and 0.53, which are consistent with the literature. However, these values were lower than those of Curley's study,27 which were 0.88 and 0.58. According to the results of this study, we should test the sensitivity and specificity of the scale when we use the scale in different populations.

The cutoff score of this study was 19, which was higher than the 16 reported in Curley's study.27 The three common diagnoses of Curley's study were pulmonary, neurological and gastrointestinal systems diseases, which differed from those of this study. This may be the cause of the difference of two cutoff scores. Another possibility is a difference in the samples.

ROC curve plotted sensitivity and 1-specificity for each possible score of the Braden Q Scale, and the curve reflects the relationship between the sensitivity and specificity, providing a visual impression of the cutoff score. The AUC is the area under the curve; the higher the AUC is, the more accurate the scale is. The AUC of the Braden Q Scale in this study was 0.57, which indicated that the predictive validity of the scale was relatively poor. Schoonhoven25 reported that the AUC of the Norton, Braden and Waterlow Scales were 0.56, 0.55 and 0.61, which are close to the results of this study. A potential cause of the low AUC of this study is that the diagnoses and physical status were different from those of the other studies.

5. Conclusions

We can conclude from this research that the value of the Braden Q Scale in the Chinese pediatric population is relatively low, and it should be optimized when used in Chinese pediatric patients. We will enlarge the sample to verify the results in a future study.

Conflicts of interest

All contributing authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff for their assistance in collecting the data.

1. Bergstrom N, Allman RM, Alvarez OM,etal. Treatment of pressure ulcers. Clinical Practice Guideline. No. 15. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. AHCPR Pub; 1994. 95-0652.

2. Allman RM, Goode PS, Burst N,etal. Pressure ulcers, hospital complications, and disease severity: impact on hospital costs and length of stay. Adv Wound Care. 1999;12:22-30.

3. Amlung SR, Miller WL, Bosley LM. The 1999 national pressure ulcer prevalence survey: A benchmarking approach. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2001;14:297-301.

4. Whittington K, Patrick M, Roberts JL. A national study of pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence in acute care hospitals. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2000;27:209-15.

5. Fernandes LM, Helena M, Calin L. Using the Braden And Glasgow Scales to predict pressure ulcer risk in patients hospitalized at intensive care units. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2008;16:973-978.

6. Willock J, Maylor M. Pressure ulcers in infants and children. Nurs Stand. 2004;18(24):56-60,62.

7. Maklebust J. Interrupting the pressure ulcer cycle. Nurs Clin North Am. 1999;34:861-871.

8. Baldwin KM. Incidence and prevalence of pressure ulcers in children. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2002;15:121-124.

9. Curley MA, Thompson JE, Amold JH. The effects of early and repeated prone positioning in pediatric patients with acute lung injury. Chest. 2000;118:156-163.

10. LU Ye-feng, LOU Jian-hua, LU Xiu-wen. Evaluation on Applying Pediatric Pressure Ulcer Assessment Scale. Nursing Journal of Chinese People's Liberation Army. 2009;26:1-4.

11. Tweed C, Tweed M. Intensive care nurses' knowledge of pressure ulcers: Development of on assessment tool and effect of an educational program. Am J Crit Care. 2008;17:338-346.

12. Willock J, Maylor M. Pressure ulcers in infants and children. Nursing Standard. 2004;24:56-62.

13. Bergstrom N, Braden BJ, Boynton P,etal. Using a research-based assessment scale in clinical practice. Nurs Clin North Am. 1995;30:539-551.

14. Quigley SM, Curley MAQ. Skin integrity in the pediatric population: preventing and managing pressure ulcers. J Soc Pediatr Nurs. 1996;1:7-18.

15. Malloy MB, Perez RC. Neonatal skin care: prevention of skin breakdown. Pediatr Nurs. 1991;17:41-48.

16. Chameides L, Hazinski MF. Textbook of pediatric advanced life support. Dallas, TX: AHA; 1994.

17. Braden B, Bergstrom N. A conceptual schema for the study of the etiology of pressure sores. Rehabil Nurs. 1987;12:8-12,16.

18. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Pressure ulcers prevalence, cost and risk assessment: Consensus development conference statement. Decubitus. 1989;2:24-28.

19. Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Guyatt GH,etal. Clinical epidemiology: a basic science for clinical medicine. 2nd ed. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1991.

20. Bergstrom N, Braden B, Kemp M,etal. Predicting pressure ulcer risk. A multisite study of the predicative validity of the Braden Scale. Nurs Res. 1998;47:261-269.

21. Smith BM, Guihan M, LaVela SL,etal. Factors predicting pressure ulcers in veterans with spinal cord injuries. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87:750-757.

22. Bergstrom N, Braden BJ. Predictive validity of the Braden scale among Black and White subjects. Nurs Res. 2002;51:398-403.

23. McLane KM, Bookout K, McCord S,etal. The 2003 national pediatric pressure ulcer and skin breakdown prevalence survey. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2004;31:168-178.

24. McCord S, McElvain V, Sachdeva R,etal. Risk factors associated with pressure ulcers in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2004;31:179-183.

25. Schoonhoven L, Haalboom JRE, Bousema MT,etal. Prospective cohort study of routine use of risk assessment scales for prediction of pressure ulcers. BMJ. 2002;325:1-5.

26. Balzer K, Pohl C, Dassen T,etal. The Norton, Waterlow, Braden and Care Dependency Scales. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2007;34:389-398.

27. Curley MAQ, Razmus IS, Roberts KE,etal. Predicting pressure ulcer risk in pediatric patients-the Braden Q Scale. Nurs Res. 2003;52:22-31.

*Corresponding author. E-mail address: renji-yy@126.com (Y. Yang). Peer review under responsibility of Shanxi Medical Periodical Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cnre.2015.01.002

- Frontiers of Nursing的其它文章

- Observation on the quality of life before and after the injection of antiangiogenic drug in the vitreous cavity of patients with wet age-related macular degeneration☆

- The Application of Multimedia Messaging Services via Mobile Phones to Support Outpatients: Home Nursing Guidance for Pediatric Intestinal Colostomy Complications☆

- Study Weariness of Vocational College Students and Reform of the Teaching Mode in Nursing Basic Technology Course☆

- A Research Report on the Prescription Rights of Chinese Nurses☆

- GUIDE FOR AUTHORS