根间相互作用对玉米与马铃薯响应异质氮的调控

吴开贤,安曈昕,范志伟,周 锋,薛国峰,吴伯志

云南农业大学农学与生物技术学院,昆明 650201

根间相互作用对玉米与马铃薯响应异质氮的调控

吴开贤,安曈昕,范志伟,周 锋,薛国峰,吴伯志*

云南农业大学农学与生物技术学院,昆明 650201

近年研究表明养分异质促进植物多样性与群落生产力的正相关性。然而,相关的促进机制还很不清楚。以农田生态系统下作物多样性群体(玉米马铃薯间作体系)为例,在盆栽条件下采用控释性氮肥构建养分异质性,通过目标植物法设计根间作用处理,探讨根系的觅养行为,植株个体生长和总生产力对土壤氮空间分布和根间作用的响应特征。结果表明:根间作用提高作物的觅养精确度(F=3.017,P=0.094),在异质性条件下马铃薯的根冠比增加(P=0.001),而玉米的根冠比则不论在均质性还是异质性条件下均显著降低(F=4.781,P=0.039);氮异质性显著地提高在根间作用下两作物的生物量生产(P=0.021),明显增加总生产力LER(Land equivalent ratio)(F=4.171,P=0.064),显著地降低相对关系指数RII(Relative interaction index)值(F=5.636,P=0.026),显著降低玉米的根冠比(F=4.273,P=0.049),增加根间作用下马铃薯的根冠比,而在无竞争下则降低。上述结果说明,非资源性的根间作用激发玉米和马铃薯对异质性氮的觅养能力,这可能是为什么异质性养分环境促进植物多样性与群体生产力正向关系的重要原因;结果还表明觅养能力的激发主要来自非资源性的根间作用机制,因此本研究验证了植物对异质性养分和竞争者的协同响应理论。而有关的非资源性根间作用机制,例如种间识别作用等值得进一步深入探讨。

氮异质性; 植物多样性; 根系觅养精确度; 生产力

因土壤的有机质含量、微生物活性、质地和含水量等的局部差异,植物根系生长空间范围内的土壤养分表现为高度的空间异质性[1- 3],即养分斑块。同时,由于复杂群体结构的驱动作用,多样性高的群体中伴随了更高的养分异质性[4]。养分异质性可改变植物对养分的利用效率和生长表现,进而调控种群和群落的结构和功能[5- 7]。近年来,有研究表明土壤养分空间异质性促进植物多样性与群落生产力的正相关性[8- 9],然而,截至目前,相关的促进机制还很不清楚。

在个体水平上,植物为适应异质性养分,其根系进化出一系列的生理和表型可塑性[10- 12]。其中觅养精确度,即植物增加高养分斑块内的根生长和生物量分配的行为,是重要的适应性响应策略[13]。但研究表明并非所有植物均对养分异质性表现出趋肥性[14],同时具有趋肥性也不必然提高植物的养分吸收和适合度[15- 16]。尽管如此,许多植物确实通过趋肥性响应养分的异质性[3],这已经得到分子水平的研究证实[17- 18]。而植物个体的生长变化必然改变物种内或种间的相互作用关系。因此,大量研究探讨养分异质性对种内或种间竞争关系的影响[5,19- 20],尤其是植物响应异质性时的觅养精确度与竞争能力的关系[21- 22],然而,这些研究主要关注觅养精确度高的植物是否相应地具有较强的竞争能力,而反过来探讨种间作用,尤其是根间作用对植物觅养精确度调控的研究则相对较少[5,23]。但相关研究有助于理解植物种群和群落的结构与功能对异质性养分的响应机制。

氮是植物生产力的主要限制因子之一。尽管氮在土壤中具有较高的移动性,然而,由于有机质的分解,土壤质地和含水量差异等因素,氮的空间异质性分布现象十分普遍[24- 25]。因此氮的异质性对植物个体和群体的影响已引起学者的关注[2,26- 27]。在农田间作生态系统中,由于不均匀施肥和群体结构复杂化[4,28],氮的异质性特点更为突出。玉米间作马铃薯是重要的旱地非豆科间作模式,在国内外均有着悠久的历史,其显著的增产效果已在世界的许多地区得到证实[29- 30]。因此,本文以该间作模式为研究对象,在盆栽的条件下采用控释性氮肥构建异质性,通过目标植物法设计根间作用处理[31],通过分析根系的觅养行为,植株个体生长和群体生产力特征,探讨根间作用对作物根系适应异质性氮有什么影响?以及土壤氮空间分布是否改变根间作用关系?力求提供科学数据以解释为什么养分异质性促进植物多样性与群落生产力的正相关性。

1 材料与方法

1.1 试验设计

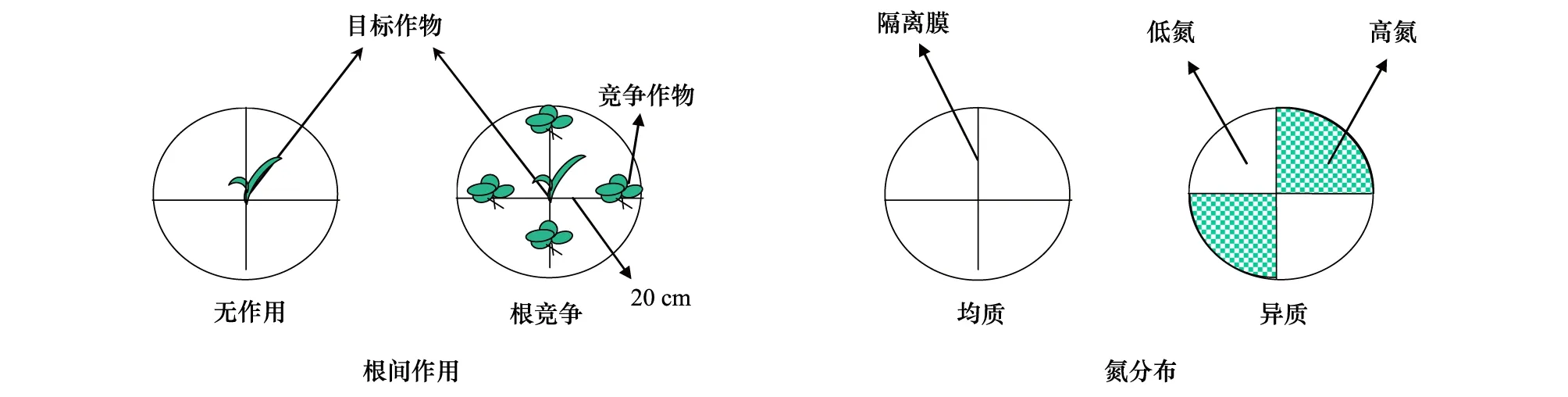

选择试验所在地区生产中广泛应用的半紧凑型玉米(云瑞6)和耐阴型马铃薯(会- 2)作为试验材料。设作物,种植方式和氮异质性三因素,其中种植方式设无竞争(即单株种植)和根间作用处理,氮异质性设均质性和异质性处理,含8个处理组合,重复8次,共64盆。处理方式如图 1所示,竞争处理采用目标植物法设计[31]:无竞争,单一植株生长在钵中央;根间作用,钵内中央种植单株目标植株,目标植株的周围以环形等距离种植4株竞争植株,竞争植株与目标植株的间距为20 cm。氮异质性处理时先将大营养盆(高50 cm,上口径60 cm,下口径40 cm)四等分,并用厚塑料膜隔开形成分室,塑料膜与盆壁相连处用强力胶水粘紧密。均质和异质处理的施氮量相同,均为纯氮0.70 g/kg基质,其中异质性处理时相邻的空间斑块内按高肥∶低肥=5∶1的比例进行不同氮施肥量处理。为有效地建立养分异质性,肥料选用控释性氮肥(含氮量26%,德钾公司)。移栽时采用分根法(Split root system)将植株的根系均分在4个分室内,试验于2011年5月—7月在日光温室内进行,各处理盆按随机摆放。

图1 盆栽下玉米与马铃薯根间作用处理的目标植物法[31]设计和氮异质性的构建(以玉米作目标植物为例)Fig.1 The diagram of the pot experiment design on the Target design[31] for root interaction treatment, which illustrated by maize as target plant and nitrogen distribution

营养盆内加入的12 kg基质,基质为试验田表土(20 cm深土层)与蛭石按体积比5∶1混合而成。其中试验田表土为山地红壤,含全氮1.4 g/kg,氨态氮4.34 mg/kg,硝态氮5.38 mg/kg,全磷3.21 g/kg,速效磷17.0 g/kg,全钾4.47 g/kg,速效钾113.6 mg/kg,有机质24.14 g/kg,pH值5.7。土壤与蛭石混合前经充分风干,用0.5 cm的网筛过滤石块和残渣;混合时加入钙镁磷5.0 g/每盆,硫酸钾9.0 g/每盆。当邻居植物长到10 cm时用透明塑料条带进行小心缚倒以减少对目标植物产生地上竞争,由于茎具有向上生长的特性,1周进行1次修正。该地上竞争去除方法对邻居植株影响相对较小[32],同时也适合个体较大的作物,如玉米。

1.2 幼苗准备

2011年5月22日,玉米种子和马铃薯块茎在1.25% 次氯酸钠中浸泡5 min消毒,用蒸馏水漂洗后,选均一饱满的玉米种子在室内培养皿上催芽5—7d后移栽;马铃薯块茎(120—150 g)沙培催芽。沙培时先用部分基质(含细沙和蛭石,体积比为1∶1)铺好苗床,苗床底放一块厚薄膜,防止根系入土导致移栽时容易扯断根系;苗床深10 cm可使根系发达,同时又不过长,铺好苗床后,将薯块顶部向上平放,再盖上5 cm厚基质,处理期间保持湿度在30%—40%,1周后,幼苗茎长至6 cm,根长至12 cm时进行移栽。为实现马铃薯的“单株”种植以降低马铃薯自身的个体效应,进行掰芽移栽,由于薯块不同部分的芽生长潜力存在差异,选生长(株高和根长)一致的顶芽移栽。移栽后每3 d进行1次浇水,保持土壤含水量在50%,且控制浇水强度,确保盆底部不发生渗流。

1.3 采样与观测

作物生长41 d后,马铃薯现蕾和玉米初花前期时采样。首先齐地面取走地上部分,然后取根系。由于玉米与马铃薯的根系难于从形态上区分,因此需要特定的方法。首先剥去营养盆底,然后小心地将其置于高1 m 的铁架上,分别将4个分室对盆壁剪开,从盆底部自下而上地轻敲土体实现根土分离,由于基质中混入了蛭石,疏松性好,因此在根土分离时对细根的损伤较小。分离后,在得到的混合根样中,由于根系固定在根颈上,可以方便地区分两作物的根系并实现分开。最后,对取样得到的植株按照茎,叶,根,根颈和块茎(马铃薯)进行分离,在70 ℃下烘至恒重,称量干物重。

1.4 数据处理与统计

(1)总生产力评估

土地当量比(LER)用于衡量不同氮空间分布下的两作物的总生产力及其优势:

式中,Yai和Ybi分别表示间作时a和b作物根间作用下的生物量,Yas和Ybs分别表示单株种植时a和b作物的生物量。当LER值>1时,表征根间作用具有生产力优势,且值越大优势越高。

(2)竞争关系评估

以生物量为基础,采用相对关系指数RII(Relative interaction index)[33]衡量间作条件下作物的竞争能力:

式中,Bi表示某作物在根间作用条件下的生物量,Bs表示某作物在单株种植条件下的生物量。当RII>0时,表示作物在竞争中得到的互利效应大于受到的竞争效应,当RII<0时,则竞争效应大于互利效应,RII=0时,作物在间作中没有受到影响。RII值越大表明相对竞争能力越强。

(3)觅养精确度分析

植物为适应土壤养分的异质性,其根系进化出一系列的生理和表型可塑性。其中增加高养分斑块内的根系生长被认为是植物对异质性养分的适应性响应,采用高氮斑块内与低氮斑块内根系生物量之比来衡量觅养精确度。比值越高,其觅养精确度越高。

(4)生物量分配分析

用根冠比,即根系生物量与茎叶生物量的比值评估作物在不同处理下地上部与地下部间的生物量分配策略。

(5)数据分析

采用SPSS17.0对所有指标进行两因素的方差分析和处理均值间的多重比较(LSD法),其中分析植株生物量和根冠比时,以种植方式和氮异质性处理为固定因素,而分析竞争关系时以作物和氮异质性为固定因素,分析觅养精确度时以作物和竞争为固定因素。显著水平均为P<0.05,分析前对方差不齐的变量进行自然对数转换。

2 结果与分析

2.1 作物生长与生产力特征

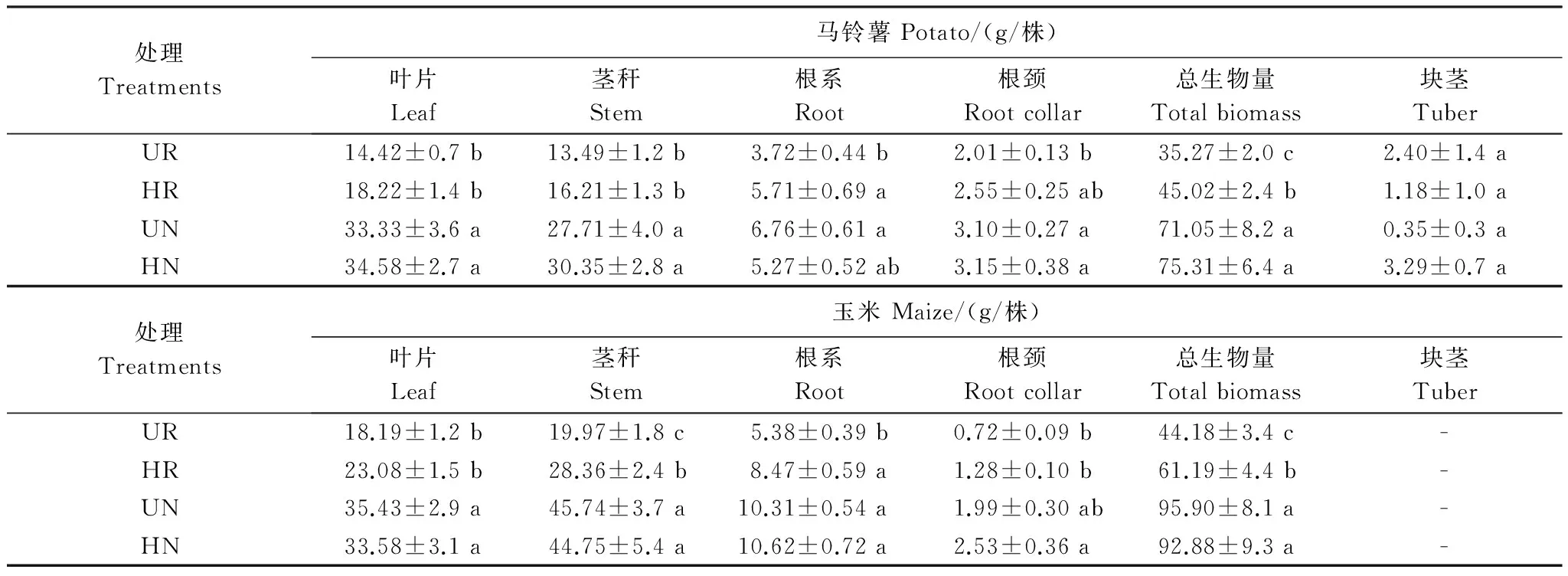

异质性氮显著地提高作物生长和生产力(表1),但这种促进作用主要体现在根间作用处理下。具体来看,对于马铃薯,无竞争下异质性氮并未显著地改变叶生物量,茎生物量,根颈和块茎生物量,但在根间作用下,异质性显著地提高马铃薯的根系(P=0.017)和总生物量(P=0.025);而对于玉米,比较无竞争和根间作用后发现,根间作用时除了叶生物量没有变化外,氮异质性显著地提高茎生物量(P=0.034),根生物量(P<0.001),根颈生物量(P=0.008)和总生物量(P=0.021),而在无竞争时变化则不显著。这些结果说明养分空间分布对作物生长的影响受到根间作用调控。从总的生产力分析来看,均质和异质下的LER值分别为1.047和1.356,前者明显低于后者,且统计上已接近显著水平(F=4.171,P=0.064),进一步表明氮异质性促进作物生长。

不论玉米还是马铃薯,根间作用均显著降低叶生物量(玉米F=31.837,P<0.001; 马铃薯F=75.567,P<0.001),茎生物量(玉米F=31.210,P<0.001; 马铃薯F=40.01,P<0.001)和根系生物量(玉米F=22.255,P<0.001; 马铃薯F=5.611,P=0.026),因此最终降低总生物量(玉米F=37.910,P<0.001; 马铃薯F=54.929,P<0.001),且这些效应不受氮分布的影响。根间作用降低作物生长可能是因为本研究中试验设计采用添加模式,在总养分不变的情况下,增加植株数量必然导致总养分资源有效性下降。

表1 氮空间分布和根间作用对玉米和马铃薯生物量的影响(均值±标准误)Table 1 Effects of nitrogen distribution and root interaction on the growth of maize and potato(means±SE)

UR:均质根间作用,HR: 异质根间作用,UN:均质无竞争,HN:异质无竞争;处理间多重比较用LSD法,同列中含不同小写字母表示处理间差异显著(P<0.05)

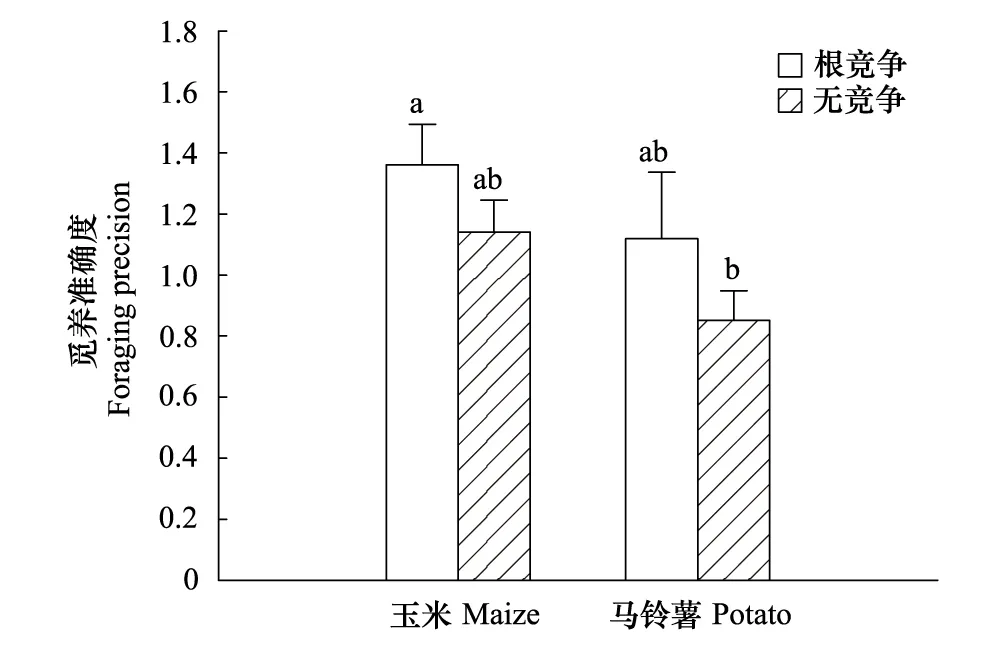

2.2 觅养精确度

根间作用明显提高作物的觅养精确度(图2),且统计上也接近显著水平(F=3.017,P=0.094),其中玉米在无竞争和根间作用下的觅养精确度分别为1.140和1. 361,而马铃薯分别为0.851和1.119。表明根间作用可激发觅养行为。同时,由于根间作用与作物因素间并不存在交互效应(F=0.028,P=0.868),因此根间作用的这一效应并不因物种差异改变。当然,两作物间的觅养精确度存在差异,即玉米显著高于马铃薯(F=4.802,P=0.037),这可能是玉米对氮的需求量大,因此对氮养分斑块的响应更敏感。

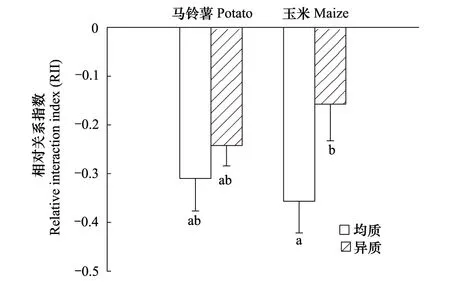

2.3 竞争关系

总体上,氮异质性降低两作物间的竞争,而不是增加(F=5.636,P=0.026,图3);多重比较发现异质性养分降低玉米受到的竞争,且统计上达到显著水平(P=0.016),而马铃薯则变化不显著。作物间的总竞争能力差异不显著(F=0.158,P=0.694),但不同氮分布处理下有较大变化,玉米的竞争优势主要体现在异质性氮条件下。

2.4 生物量分配

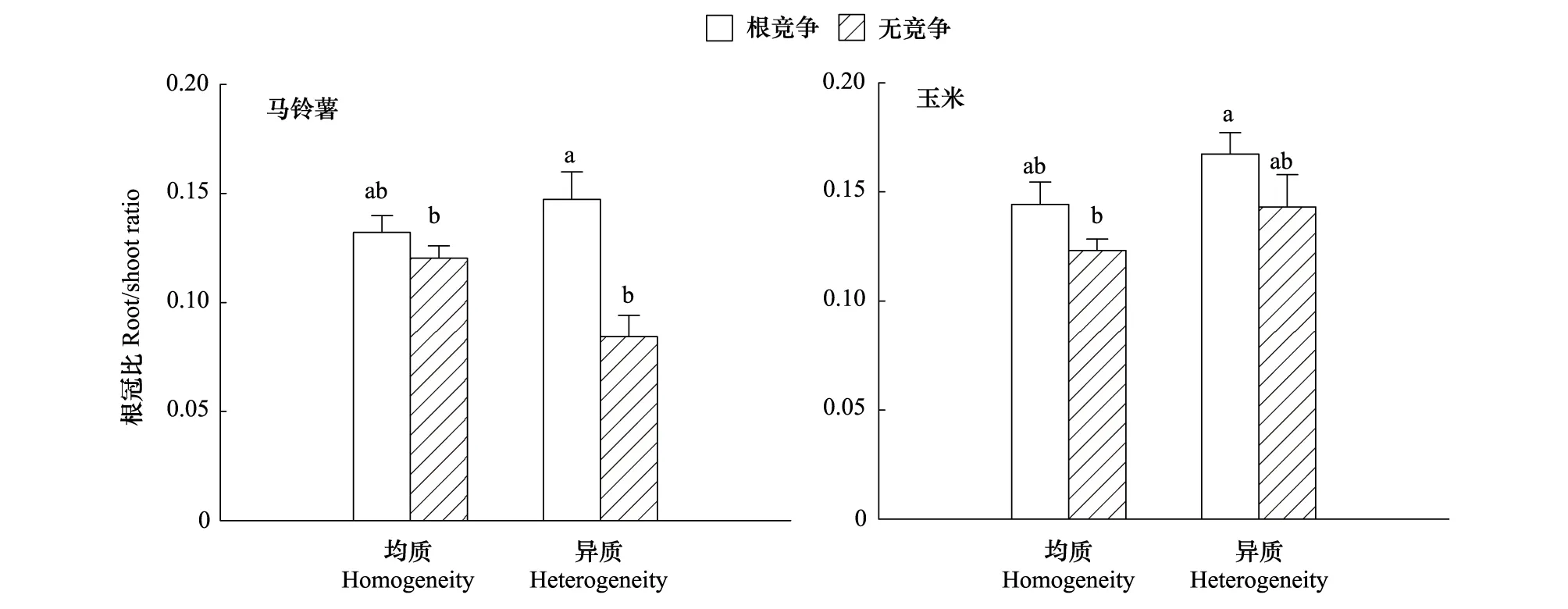

从马铃薯来看,氮异质性影响根冠比,但在统计上差异不显著(F=0.648,P=0.429,图4),事实上,是否降低取决于竞争方式,在有竞争时异质性增加根冠比,而在无竞争时才降低根冠比。但是根间作用显著地增加根冠比(F=8.436,P=0.008),其影响因氮异质性程度而不同(F=3.938,P=0.059),即在均质性下的增加不显著,在异质性下则显著(P=0.001),说明在异质性下马铃薯对竞争的响应更敏感,或者受到的竞争相对较强;从玉米来看,根间作用(F=4.781,P=0.039,图4)和氮异质性均显著地增加根冠比(F=4.273,P=0.049),但两者间不存在交互效应(F=0.025,P=0.876)。这些结果说明在调节作物的生物量分配时,根间作用和氮异质性的关系随作物不同改变,这可能是因为两作物对氮的需求存在差异。

图2 根间作用对玉米与马铃薯根系觅养准确度的影响(均值±SE)Fig.2 Effects of root interaction on the foraging precision of maize and potato (means ± SE)图中不同字母表示处理间差异显著(P<0.05,LSD法)

图3 氮异质性对玉米与马铃薯根间关系的影响(均值±SE)Fig.3 The root interaction of maize and potato under different nitrogen distribution (means±SE)图中不同字母表示处理间差异显著(P < 0.05,LSD法)

图4 氮异质性和根间作用对玉米与马铃薯根冠比的影响(均值±SE)Fig.4 Effects of patch nitrogen and root interaction on the root: shoot ratio of maize and potato (means±SE)图中不同字母表示处理间差异显著(P < 0.05,LSD法)

3 讨论

3.1 植物生产力与觅养精确度的关系

本研究结果表明,根间作用在异质性氮环境下提高植物总生产力,这与已有研究结果一致[8- 9],即异质性的氮促进植物多样性与生产力的正相关性。这可能是因为根间作用下植物的觅养能力增加,主要表现为觅养精确度的提高。当然,觅养精确度的提高并不必然促进养分的利用[15],而且根系的生理可塑也可以改变养分的吸收,但在本研究中,由于在无竞争处理时异质性并未增加植物生物量;同时异质性氮环境下植物间的竞争强度也没有增加,反而呈下降趋势。这表明在异质性氮条件下,玉米与马铃薯的根间互利关系增强,从而提高觅养精确度,促进玉米和马铃薯对氮的补偿性利用(表 1)。当然,与其他相关研究类似[34],本研究通过控释性肥料构建相对稳定的氮养分异质性格局,如果氮养分斑块持续时间较短,觅养精确度的提高可能会增加养分获取的成本,例如降低地上部的生物量分配,因此在长期的时间尺度上,根间作用是否能够通过提高觅养精确度来促进群落生产力尚不能肯定。当然,在短期内,或者处于动态的养分异质性下时,如果根系的生理可塑增加,例如增加根系活力,则生理可塑可能比表型可塑具有更大的重要性。这说明,有必要在动态的养分异质性环境下进一步探讨根间作用下植物的觅养行为,尤其是研究生理上的根系觅养能力可塑特征。

3.2 根间作用对觅养能力的激发机制

最近,Cahill 在其开创性研究中发现,苘麻(A.theophrasti)根系的水平生长幅度在没有竞争时不受养分分布的影响,有竞争时则在均质性养分环境中受到严重抑制,而异质性养分环境中只受到轻微影响。因此Cahill提出,植物对异质性养分和竞争作出响应,也同时对邻近的竞争者作出非资源性介导的响应[23]。本研究数据表明,根间作用可提高玉米和马铃薯对异质性氮的觅养精确度,激发其觅养能力。这与Cahill的观点一致,即植物根系能够整合异质性养分和邻近者的根间作用信息,但本研究从植物种间作用(群落水平)而不是种内作用(种群水平)的角度验证并支持这一假说。当然,存在根间作用时,土壤养分的有效性必然下降,因此植物为适应竞争可能提高觅养精确度。但研究表明在低养分有效性下,根系的觅养行为或能力反而降低[35- 38],事实上,本研究中氮异质性并未增加根间竞争强度(图3),因此尽管没有定量探讨养分资源的消耗情况,这些结果初步表明觅养精确度的提高并不太可能是资源竞争的后果,而非资源性的根间作用可能是觅养能力被激发的重要机制。

需要指出的是,在Cahill的研究中,种内的根间作用下苘麻的觅养行为受到抑制,而本研究中种间的根间作用下玉米和马铃薯的根系觅养行为得到激发。这说明群体和群落环境下根系的觅养行为存在差别。形成这些差别的非资源性机制非常值得探讨。近年来研究表明植物与邻居植株间存在亲缘识别作用,即植物能够通过根系分泌物为信号物质来区分邻近植株的遗传身份,并作出差异响应[39- 40]。根据Hamilton的亲缘选择理论(Kin selection theory)[41],当植物根系面对遗传上相近或等同的邻居植株时,植物可能倾向于减小觅养行为;反之,当遭遇在遗传学上亲缘较远的邻近植物时则可能增加。当然,植株间的非资源性作用也可通过跨营养级的反馈调控间接地来实现。以微生物为例,种间作用通过阻隔和稀释作用抑制病原微生物的传播和繁殖[42- 43];或者促进微生物的物种多样性,进而通过微生物间的拮抗和竞争[44- 45]间接地促进另一植物觅养行为或能力。上述推测均有待于进一步的研究验证。

3.3 觅养精确度对种间关系的调控

养分异质性下植物觅养精确度的改变将直接影响植物群体或群落下个体间的竞争关系[7]。本研究中,均质性氮条件下,玉米的竞争优势不明显,甚至弱于马铃薯,但在异质性氮条件下,则具有相对强的竞争能力。Reynolds强调,在探讨养分异质性对植物群体功能的调控时需要考虑养分斑块的性质[46]。例如在探讨群体的生产力时,理论上,当养分斑块的范围小于根系生长可到达的土壤空间时,由于植物需要的养分总体上相同,根系觅养行为将导致植物间的根系生长集中在高养分斑块内,因而会导致竞争加剧,总生产力下降。本研究表明,氮异质性降低两作物受到的竞争,而不是增加竞争(图3),同时总生产力也增加。这与其他研究结果一致[8- 9]。

氮异质性降低两作物间竞争性关系的可能原因如下:首先,本研究中根间作用互补性地提高植物的觅养能力,促进异质性土壤氮的利用;其次,根间作用下两作物对异质性养分的响应程度有显著差异,这可能促进生态位分离。Mommer研究表明,竞争条件下,植物的根系对氮的觅养行为取决于该植物对氮的竞争能力,其中较强竞争者具有较大的觅养精确性,而较弱者则反之,因而并不表现出强烈的竞争[47]。事实上,玉米对氮的需求较马铃薯大,具有更强的竞争能力,可能是其表现出更高的觅养精确性的原因(图2);此外,近年的研究表明植物能够感知环境和资源的瞬时线性变化,并作出预期的适应性响应[48]。例如,Shemesh利用分根法,研究发现豌豆的根系生长在有效性逐渐降低的高养分条件受到抑制,而在有效性逐渐升高的低养分斑块中反而增加[49]。因此,当一种植物根系生长速度快,更早地到达高养分斑块,或者具有较大吸收速率时,斑块内的养分存在下降的趋势信号,另一种植物根系感知这一信号后,其觅养可能会转向没有竞争对象的低养分斑块。从而,根系的觅养将选择进入未被“占领”区域[50]。

4 结论

异质性养分条件下,根间作用提高玉米和马铃薯的生物量生产,这主要得益于作物根系觅养能力的提高,因此本研究一定程度上回答了为什么异质性养分环境促进植物多样性与群体生产力的正向关系;另外,本研究初步发现根系觅养能力的提高主要来自非资源性的根间作用机制,但具体的相关机制,例如种间识别作用等值得深入探讨。

[1] Jackson R B, Caldwell M M. The scale of nutrient heterogeneity around individual plants and its quantification with geostatistics. Ecology, 1993, 74(2): 612- 614.

[2] Robinson D, Hodge A, Griffiths B S, Fitter A H. Plant root proliferation in nitrogen-rich patches confers competitive advantage. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Proceedings of the Royal Society Series B: Biological Sciences, 1999, 266(1418): 431- 437.

[3] Hodge A. The plastic plant: root responses to heterogeneous supplies of nutrients. New Phytologist, 2004, 162(1): 9- 24.

[4] Ettema C H, Wardle D A. Spatial soil ecology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2002, 17(4): 177- 183.

[5] Wijesinghe D K, John E A, Hutchings M J. Does pattern of soil resource heterogeneity determine plant community structure? An experimental investigation. Journal of Ecology, 2005, 93(1): 99- 112.

[6] O′Brien E E, Gersani M, Brown J S. Root proliferation and seed yield in response to spatial heterogeneity of below-ground competition. New Phytologist, 2005, 168(2): 401- 412.

[7] Hutchings M J, John E A, Wijesinghe D K. Toward understanding the consequences of soil heterogeneity for plant populations and communities. Ecology, 2003, 84(9): 2322- 2334.

[8] García Palacios P, Maestre F T, Gallardo A. Soil nutrient heterogeneity modulates ecosystem responses to changes in the identity and richness of plant functional groups. Journal of Ecology, 2011, 99(2): 551- 562.

[9] Tylianakis J M, Rand T A, Kahmen A, Klein A M, Buchmann N, Perner J, Tscharntke T. Resource heterogeneity moderates the biodiversity-function relationship in real world ecosystems. PLoS Biology, 2008, 6(5): e122.

[10] Kembel S W, Cahill Jr J F. Plant phenotypic plasticity belowground: a phylogenetic perspective on root foraging trade-offs. The American Naturalist, 2005, 166(2): 216- 230.

[11] de Kroon H, Mommer L. Root foraging theory put to the test. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2006, 21(3): 113- 116.

[12] McNickle G G, Cahill J F. Plant root growth and the marginal value theorem. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2009, 106(12): 4747- 4751.

[13] Cahill J F Jr, McNickle G G. The behavioral ecology of nutrient foraging by plants. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 2011, 42(1): 289- 311.

[14] Kembel S W, de Kroon H, Cahill J F Jr, Mommer L. Improving the scale and precision of hypotheses to explain root foraging ability. Annals of Botany, 2008, 101(9): 1259- 1301.

[15] Maestre F T, Reynolds J F. Small-scale spatial heterogeneity in the vertical distribution of soil nutrients has limited effects on the growth and development ofProsopisglandulosaseedlings. Plant Ecology, 2006, 183(1): 65- 75.

[16] Jansen C, van Kempen M M L, Bögemann G M, Bouma T J, de Kroon H. Limited costs of wrong root placement inRumexpalustrisin heterogeneous soils. New Phytologist, 2006, 171(1): 117- 126.

[17] Forde B G, Walchliu P A. Nitrate and glutamate as environmental cues for behavioural responses in plant roots. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2009, 32(6): 682- 693.

[18] Desnos T. Root branching responses to phosphate and nitrate. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 2008, 11(1): 82- 87.

[19] Day K J, John E A, Hutchings M J. The effects of spatially heterogeneous nutrient supply on yield, intensity of competition and root placement patterns inBrizamediaandFestucaovina. Functional Ecology, 2003, 17(4): 454- 463.

[20] Rajaniemi T K. Root foraging traits and competitive ability in heterogeneous soils. Oecologia, 2007, 153(1): 145- 152.

[21] Schiffers K, Tielb Rger K, Tietjen B, Jeltsch F. Root plasticity buffers competition among plants: theory meets experimental data. Ecology, 2011, 92(3): 610- 620.

[22] Fransen B, de Kroon H, Berendse F. Soil nutrient heterogeneity alters competition between two perennial grass species. Ecology, 2001, 82(9): 2534- 2546.

[23] Cahill Jr J F, McNickle G G, Haag J J, Lamb E G, Nyanumba S M, St Clair C C. Plants integrate information about nutrients and neighbors. Science, 2010, 328(5986): 1657- 1657.

[24] Lofton J, Weindorf D C, Haggard B, Tubana B. Nitrogen variability: a need for precision agriculture. Agricultural Journal, 2010, 5(1): 6- 11.

[25] Hodge A, Robinson D, Griffiths B, Fitter A. Nitrogen capture by plants grown in N-rich organic patches of contrasting size and strength. Journal of Experimental Botany, 1999, 50(336): 1243- 1252.

[26] Hodge A, Stewart J, Robinson D, Griffiths B S, Fitter A H. Spatial and physical heterogeneity of N supply from soil does not influence N capture by two grass species. Functional Ecology, 2000, 14(5): 645- 653.

[27] Hodge A, Robinson D, Griffiths B S, Fitter A H. Why plants bother: root proliferation results in increased nitrogen capture from an organic patch when two grasses compete. Plant, Cell & Environment, 1999, 22(7): 811- 820.

[28] Parker S S, Seabloom E W, Schimel J P. Grassland community composition drives small-scale spatial patterns in soil properties and processes. Geoderma, 2012, 170(15): 269- 279.

[29] Sharaiha R K, Battikhi A. A study on potato/corn intercropping-microclimate modification and yield advantages. Agricultural Sciences, 2002, 29(2): 97- 108.

[30] Midmore D J, Berrios D, Roca J. Potato (Solanumspp.) in the hot tropics V. Intercropping with maize and the influence of shade on tuber yields. Field Crops Research, 1988, 18(2/3): 159- 176.

[31] Clements F E, Weaver J, Hanson H. Plant Competition: An Analysis of the Development of Vegetation. Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1926.

[32] Wilson S D, Tilman D. Component of plant competition along an experimental gradient of nitrogen availability. Ecology, 1991, 72(3): 1050- 1065.

[33] Armas C, Ordiales R, Pugnaire F I. Measuring plant interactions: a new comparative index. Ecology, 2004, 85(10): 2682- 2686.

[34] Nakamura R, Kachi N, Suzuki J I. Root growth and plant biomass inLoliumperenneexploring a nutrient-rich patch in soil. Journal of Plant Research, 2008, 121(6): 547- 557.

[35] Bilbrough C J, Caldwell M M. The effects of shading and N status on root proliferation in nutrient patches by the perennial grassAgropyrondesertorumin the field. Oecologia, 1995, 103(1): 10- 16.

[36] Maestre F T, Reynolds J F. Amount or pattern? Grassland responses to the heterogeneity and availability of two key resources. Ecology, 2007, 88(2): 501- 511.

[37] Maestre F T, Reynolds J F. Nutrient availability and atmospheric CO2partial pressure modulate the effects of nutrient heterogeneity on the size structure of populations in grassland species. Annals of Botany, 2006, 98(1): 227- 235.

[38] Maestre F T, Bradford M A, Reynolds J F. Soil nutrient heterogeneity interacts with elevated CO2and nutrient availability to determine species and assemblage responses in a model grassland community. New Phytologist, 2005, 168(3): 637- 650.

[39] Dudley S A, File A L. Kin recognition in an annual plant. Biology Letters, 2007, 3(4): 435- 438.

[40] Fang S, Gao X, Deng Y, Chen X, Liao H. Crop root behavior coordinates phosphorus status and neighbors: from field studies to three-dimensional in situ reconstruction of root system architecture. Plant Physiology, 2011, 155(3): 1277- 1285.

[41] Hamilton W D. The genetical evolution of social behaviour II. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 1964, 7(1): 17- 52.

[42] Keesing F, Holt R D, Ostfeld R S. Effects of species diversity on disease risk. Ecology Letters, 2006, 9(4): 485- 498.

[43] de Kroon H, Hendriks M, van Ruijven J, Ravenek J, Padilla F M, Jongejans E, Visser E J W, Mommer L. Root responses to nutrients and soil biota: drivers of species coexistence and ecosystem productivity. Journal of Ecology, 2012, 100(1): 6- 15.

[44] Hibbing M E, Fuqua C, Parsek M R, Peterson S B. Bacterial competition: surviving and thriving in the microbial jungle. Nature, 2009, 8(1): 15- 19.

[45] Maron J L, Marler M, Klironomos J N, Cleveland C C. Soil fungal pathogens and the relationship between plant diversity and productivity. Ecology Letters, 2011, 14(1): 36- 41.

[46] Reynolds H L, Mittelbach G G, Darcyhall T L, Houseman G R, Gross K L. No effect of varying soil resource heterogeneity on plant species richness in a low fertility grassland. Journal of Ecology, 2007, 95(4): 723- 733.

[47] Mommer L, van Ruijven J, Jansen C, van de Steeg H M, de Kroon H. Interactive effects of nutrient heterogeneity and competition: implications for root foraging theory? Functional Ecology, 2011, 26(1): 66- 73.

[48] Shemesh H, Ovadia O, Novoplansky A. Prioritized contingencies: context-dependent regeneratory effects of grazer saliva. Plant Ecology, 2012, 213(1): 167- 174.

[49] Shemesh H, Arbiv A, Gersani M, Ovadia O, Novoplansky A. The effects of nutrient dynamics on root patch choice. Plos One, 2010, 5(5): e10824.

[50] Semchenko M, Zobel K, Hutchings M J. To compete or not to compete: an experimental study of interactions between plant species with contrasting root behaviour. Evolutionary Ecology, 2010, 24(6): 1433- 1445.

Effects of root interactions on the response of maize and potato to heterogeneous nitrogen

WU Kaixian, AN Tongxin, FAN Zhiwei, ZHOU Feng, XUE Guofeng, WU Bozhi*

CollegeofAgronomyandBiotecnology,YunnanAgriculturalUniversity,Kunming650201,China

Soil nutrient distribution is highly heterogeneous at the plant root system level because of the diversity of soil composition. The heterogeneity of soil nutrients plays an important role in determining plant community structure and function. Recently, research has shown that soil nutrient heterogeneity increases the importance of plant diversity in community productivity. However, knowledge on the mechanism behind this phenomenon is currently lacking. Soil nutrient heterogeneity affects plant root foraging behavior and individual growth, which in turn affects the community structure and function. Therefore, for a better understanding of why there is a positive relationship between plant diversity and community productivity under soil nutrient heterogeneity conditions, it is very important to explore how plant root interactions affect root foraging behavior. Because of the application of fertilizer and the complex community composition, soil nutrient heterogeneity should be more typical in a multi-cropping system than in natural or monoculture systems. Therefore in this study, a typical intercropping system of maize and potato was chosen as a case study, and a pot experiment was conducted. The crops were planted in large pots with controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer applied homogeneously or heterogeneously, and with or without root interaction. Root interaction was achieved by the classical method of target design. At the flowering stage, plant biomass and yield were measured and the relative interaction index (RII), root foraging precision (the ratio of root biomass between higher and lower nitrogen patch), and land equivalent ratio (LER) were calculated to explore the response characteristics of crop growth to nitrogen heterogeneity and root interaction. The results showed that root interaction increased the foraging precision for both crops (F=3.017,P=0.094), and increased the root: shoot ratio for potato under nitrogen heterogeneity (P=0.001), but reduced the root: shoot ratio for maize regardless of nitrogen distribution (F=4.781,P=0.039). Nitrogen heterogeneity significantly improved biomass production for both crops (P=0.021), increased the LER (F=4.171,P=0.064), and significantly decreased the RII values (F=5.636,P=0.026) under root interaction conditions. Nitrogen heterogeneity significantly reduced the root: shoot ratio of maize (F=4.273,P=0.049), but increased the root: shoot ratio of potato in root interaction conditions, and decreased it in no root interaction conditions. This study suggested that root interaction can stimulate plant foraging behavior, which could be a key reason for the increase in the importance of plant diversity in community productivity under soil nutrient heterogeneity conditions. The data also showed that the non-resource root interaction, but not the resource root interaction, stimulates plant foraging behavior, which is in accordance with the theory that plants can integrate information about nutrients and neighbors, or is related to species-specific pathogenic microorganisms. Studies on more species and different environments are required to investigate this further. Further study is also required on the effects of root foraging behavior stimulated by plant root interactions on other community functions, such as structure or stability. Finally, it is necessary to investigate the non-resource mechanisms of root interactions such as recognition between plants, which stimulate plant root foraging behavior.

nitrogen heterogeneity; plant diversity; root foraging precision; productivity

国家重点基础研究发展计划(973)项目(2011CB100402)

2013- 03- 26;

日期:2014- 03- 25

10.5846/stxb201303260522

*通讯作者Corresponding author.E-mail: Bozhiwu@hotmail.com

吴开贤,安曈昕,范志伟,周锋,薛国峰,吴伯志.根间相互作用对玉米与马铃薯响应异质氮的调控.生态学报,2015,35(2):508- 516.

Wu K X, An T X, Fan Z W, Zhou F, Xue G F, Wu B Z.Effects of root interactions on the response of maize and potato to heterogeneous nitrogen.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2015,35(2):508- 516.