心房颤动发作的长程监测

·综述·

心房颤动发作的长程监测

张圣洁 李广平

心房颤动; 心电描记术, 便携式

心房颤动是临床上一种常见的心律失常类型。近年来,由于人口老龄化和人均寿命延长等因素使得高血压、冠心病等老年病的患病率逐年升高。这些疾病可以促进心房颤动的发生,因而心房颤动的发生率在全球范围内呈逐渐上升的趋势。欧洲的心房颤动患者现已多达600万人,预计在未来50年间,这个数字至少还会增加一倍[1]。而据统计,我国心房颤动的总患病率为0.77%,根据中国标准人口构成校正后为0.61%,略高于国际上相关研究结果。心房颤动可诱发并加重心力衰竭,引发脑卒中,极大地降低患者的生活质量,甚至可以导致死亡[2]。因此,如何提高心房颤动检出率、评估心房颤动风险、控制病情进展、改善疾病预后已成为临床亟待解决的问题。然而,由于部分阵发心房颤动患者心房颤动发作不频繁,且部分心房颤动患者房颤发作时并无临床症状,因此难以通过短程心电图检查发现。而长程动态心电监测可通过延长监测时间提高心房颤动的检出率,这对延缓并发症的出现和进展,改善患者的生活质量,提高生存率有重要的意义。本文将从心房颤动的心电监测手段、指标以及时程与频率等三方面对此领域的最新进展做一综述。

1 房颤发作的心电监测手段

目前常用的动态心电记录器共有两种类型。第一类是持续记录器,临床上常用的Holter心电图就是此种记录器。这种仪器的佩戴时间通常在24~48 h之间,可以记录出现在这一时间段内的全部心电图变化以及相应的症状。由于记录时间较长,24 h Holter对心房颤动的检出率相对高于静息短程心电图。然而,由于Holter仅能对有限时间内的心电图进行持续记录,因此这类记录器更适用于检出发作频繁的心电事件。对于发作不规律的阵发心房颤动而言,短时程Holter检查并不是十分理想的监测手段。目前关于心房颤动的专家共识也都不再将24 h短程Holter推荐为阵发心房颤动的首选检测手段[3-4]。近来,一些学者通过研究发现,增加Holter的检查频率和记录时间可以提高其对心房颤动,特别是无症状心房颤动的检出率,从而提高了Holter对心房颤动发作的监测价值[5-6]。

另一类则称为间断记录器(intermittent recorders)。此类记录器的佩戴时间长达数周到数月,可以通过对佩戴者的心电图变化进行长期监测,从中发现发作不频繁的心电事件,并对其进行短暂记录,可进一步分为植入式心电记录器和体外心电记录器两类。植入式心电记录器需行皮下置入,通过电极持续记录单一导联的心电图,但仅储存其中的一小部分。它的体积和重量均小于传统起搏器,电池电量可以持续使用约18~24个月,总记录时间上限为42 min。记录器可通过患者手动触发或程序控制自动触发两种方式进行心电资料的冻结与储存,其所记录的心电图数据可远程传输至程控仪以进行分析。新一代起搏器、埋藏式心脏复律除颤器以及实时心电监护器也具有植入式心电记录器的功能[7-9],但非起搏适应证者不宜作为心房颤动的评估检测手段。

植入式心电记录器的优势在于监测时程较长,使其更易检出发作不频繁或无症状心律失常事件[8-11],因此被认为是心房颤动尤其是无症状房颤检出的金标准[12]。其缺点则是价格昂贵且为有创检查,一定程度上限制了它的应用。而体外心电记录器的记录触发机制与植入式心电记录器相同,可用于心房颤动患者进行长程心电监测及心律失常事件记录[13],且无需有创植入,携带方便,可将所记录的数据存储在记录器中,再通过直接提交或经电话线传输两种方式提交心电信息[14],因此更具临床实用性。其中,电话传输心电图由于有效监测时间长、无需粘贴电极、心电信息可实时传输至医院监测中心等特点使此类记录器便于长周期使用。对于阵发心房颤动而言,电话传输心电图较标准心电图和24 h Holter更适用于心房颤动发作的心电监测。

2 房颤发作的心电监测指标

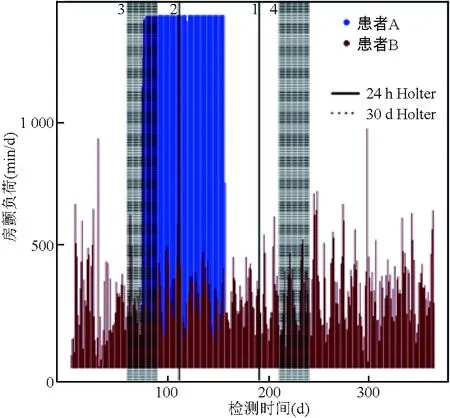

心电监测的技术进步为心房颤动的心律评价提供了技术依托,使得心房颤动发作的评价完成了从“质”到“量”的飞跃。目前人们常用的心房颤动发作评价指标主要是心房颤动负荷(atrial fibrillation burden),即患者心房颤动发作时间占总监测时间的百分比,多用于评价心房颤动患者的血栓栓塞风险[15-16]和射频消融手术效果[17]。心电监测检出心房颤动的敏感性除了受到心房颤动负荷的影响之外,还与心房颤动发作在时间上的分布趋势相关。为了更精准地对心房颤动发作进行评价,Charitos等[5]将心房颤动发作在时间上的集中趋势定义为房颤密度(atrial fibrillation burden density)。心房颤动负荷与心房颤动密度在心房颤动心电监测的时程和设备的选择上起着十分重要的作用。

尽管患者A与患者B的心房颤动负荷相似,但由于心房颤动密度的不同使得其心房颤动的检出率也不相同(图1)。患者B每天的心房颤动发作时间相对平均,因此30 d Holter与24 h Holter的心房颤动检出率相同,敏感度均高达100%。而患者A则不同,其较高的心房颤动密度使得随机30 d Holter发现心房颤动发作的几率高于随机24 h Holter。对于整个心房颤动患者群体而言,心房颤动密度是影响Holter检出敏感性的主要指标。当心房颤动负荷水平相当时,心房颤动密度高的患者检出心房颤动的敏感性低于心房颤动密度低的患者,而延长心电监测时间可以提高其对心房颤动的检出率。当我们为患者选择合理的心电监测手段时,心房颤动负荷和心房颤动密度也是重要的选择依据之一。患者的心房颤动负荷越低、密度越高,植入式心电记录器的心房颤动检出率相对Holter而言就越高。因此低心房颤动负荷、高心房颤动密度的心房颤动患者更适合选用植入式心电记录器进行心电监测。

图1 Charitos等[5]的研究中所示的患者A与患者B的心电信息记录结果比较 二者心房颤动负荷相似,分别为A=0.22,B=0.21。但由于二者的心房颤动类型不同,其心房颤动发作在时间上的分布趋势差别很大。患者A发作时间相对集中,心房颤动密度较高,而患者B的发作时间分散,心房颤动密度较低

3 房颤发作的心电监测时程与频率

由于阵发心房颤动发作时间具有不定性,因此心电监测的时程越长、频率越高,Holter检出心房颤动的可能性和准确性也就越高[18]。Mulder等[6]通过对96例阵发心房颤动患者进行7 d Holter监测发现,随着时间的推移,Holter检出心房颤动的敏感度及阴性预测值逐渐增高(表1)。延长监测时间可以提高心房颤动的检出率,但这并不是说Holter监测的时程越长越好,过长的监测时程对Holter的敏感性并没有明显的提高[19]。Charitos等[5]的研究显示,一次30 d Holter检出心房颤动的敏感度为0.65,而3次7 d Holter可以达到同样的敏感度,同时缩短了总监测时程(图2)。而且,监测时程越长,患者的耐受性和依从性就越差,反不利于心房颤动的检出,因此Holter的监测时程不宜过长[19]。

表1 不同监测时间Holter检查的敏感度>及阴性预测值的对比[6](%)

图2 Charitos等[5]的研究中所示的不同监测时程Holter探知心房颤动敏感度的对比 图中圆点代表监测次数,一次30 d Holter检出心房颤动的敏感度为0.65,而3次7 d Holter可以达到同样的敏感度,同时缩短了总监测时程,单次检测时间越短,达到同样的敏感度所需要的监测频率也相应增多。7 d Holter所需的总监测时间较短,监测频率较少,是较为理想的心房颤动监测方式

7 d Holter以其适当的监测时程和较高的敏感度成为了可以媲美电话传输心电图的心电监测手段。但一次7 d Holter所记录的心电信息长达168 h,不便于进行心电分析。为缩短分析时间,Roten等[4]希望用7 d间断Holter来代替7 d连续Holter进行心电监测。由于这种Holter仅在系统识别心律失常发生后才记录一段心电图,故与7 d连续Holter相比,其有效记录时程较短,敏感性较低,且仅能进行定性分析,不适宜作为心房颤动负荷和密度评估和心房颤动检出的分析方法。因此,尽管7 d连续Holter有漏检无症状心房颤动可能[20],但目前仍多推荐用其进行心房颤动的心电监测。

心房颤动是一种常见的心律失常类型,具有高的致死率和致残率。由于近年来心房颤动的现患率的逐年升高,使得心房颤动发作的心电监测变得愈加重要。根据心房颤动负荷和心房颤动密度选择适合的动态心电记录器进行长程心电监测可以提高心房颤动的检出率。7 d连续Holter监测以其适当的监测时程和较高的敏感性成为目前首推的心房颤动心电监测手段。

[1] Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) [J]. Eur Heart J, 2010,31:2369-2429.

[2] Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association [J]. Eur Heart J, 2012,33:2719-2747.

[3] Calkins H, Kuck KH, Cappato R, et al. 2012 HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for patient selection, procedural techniques, patient management and follow-up, definitions, endpoints, and research trial design: a report of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Task Force on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. Developed in partnership with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society (ECAS); and in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of the American College of Cardiology Foundation, the American Heart Association, the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society, the European Heart Rhythm Association, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society, and the Heart Rhythm Society [J]. Heart Rhythm, 2012,9:632-696.

[4] Roten L, Schilling M, Haberlin A, et al. Is 7-day event triggered ECG recording equivalent to 7-day Holter ECG recording for atrial fibrillation screening [J]? Heart, 2012,98:645-649.

[5] Charitos EI, Stierle U, Ziegler PD, et al. A comprehensive evaluation of rhythm monitoring strategies for the detection of atrial fibrillation recurrence: insights from 647 continuously monitored patients and implications for monitoring after therapeutic interventions [J]. Circulation, 2012,126:806-814.

[6] Mulder AA, Wijffels MC, Wever EF, et al. Arrhythmia detection after atrial fibrillation ablation: value of incremental monitoring time [J]. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol, 2012,35:164-169.

[7] Botto GL, Padeletti L, Santini M, et al. Presence and duration of atrial fibrillation detected by continuous monitoring: crucial implications for the risk of thromboembolic events [J]. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol, 2009,20:241-248.

[8] Hindricks G, Piorkowski C. Atrial fibrillation monitoring: mathematics meets real life [J]. Circulation, 2012,126:791-792.

[9] Ziegler PD, Koehler JL, Verma A. Continuous versus intermittent monitoring of ventricular rate in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation [J]. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol, 2012,35:598-604.

[10] Hanke T, Charitos EI, Stierle U, et al. Twenty-four-hour holter monitor follow-up does not provide accurate heart rhythm status after surgical atrial fibrillation ablation therapy: up to 12 months experience with a novel permanently implantable heart rhythm monitor device [J]. Circulation, 2009,120:S177-S184.

[11] Ziegler PD, Glotzer TV, Daoud EG, et al. Detection of previously undiagnosed atrial fibrillation in patients with stroke risk factors and usefulness of continuous monitoring in primary stroke prevention [J]. Am J Cardiol, 2012,110:1309-1314.

[12] Hindricks G, Pokushalov E, Urban L, et al. Performance of a new leadless implantable cardiac monitor in detecting and quantifying atrial fibrillation: Results of the XPECT trial [J]. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol, 2010,3:141-147.

[13] Pokushalov E, Romanov A, Corbucci G, et al. Use of an implantable monitor to detect arrhythmia recurrences and select patients for early repeat catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: a pilot study [J]. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol, 2011,4:823-831.

[14] Rosenberg MA, Samuel M, Thosani A, et al. Use of a noninvasive continuous monitoring device in the management of atrial fibrillation: a pilot study [J]. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol, 2013,36:328-333.

[15] Ziegler PD, Glotzer TV, Daoud EG, et al. Incidence of newly detected atrial arrhythmias via implantable devices in patients with a history of thromboembolic events [J]. Stroke, 2010,41:256-260.

[16] Glotzer TV, Daoud EG, Wyse DG, et al. The relationship between daily atrial tachyarrhythmia burden from implantable device diagnostics and stroke risk: the TRENDS study [J]. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol, 2009,2:474-480.

[17] Beukema R, Beukema WP, Sie HT, et al. Monitoring of atrial fibrillation burden after surgical ablation: relevancy of end-point criteria after radiofrequency ablation treatment of patients with lone atrial fibrillation [J]. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg, 2009,9:956-959.

[18] Mulder AA, Wijffels MC, Wever EF, et al. Freedom from paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after successful pulmonary vein isolation with pulmonary vein ablation catheter-phased radiofrequency energy: 2-year follow-up and predictors of failure [J]. Europace, 2012,14:818-825.

[19] Edgerton JR, Mahoney C, Mack MJ, et al. Long-term monitoring after surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation: how much is enough [J]? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2011,142:162-165.

[20] Healey JS, Connolly SJ, Gold MR, et al. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke [J]. N Engl J Med, 2012,366:120-129.

(本文编辑:周白瑜)

Long-term electrocardiographic monitoring methods and assessing indices of atrial fibrillation occurence and burden

ZhangShengjie,LiGuangping.

DepartmentofCardiology,SecondHospitalofTianjinMedicalUniversity,TianjinInstituteofCardiology,Tianjin300211,China

LiGuangping,Email:tjcardiol@126.com

Atrial fibrillation; Electrocardiography, ambulatory

10.3969/j.issn.1007-5410.2015.03.016

300211天津心脏病学研究所,天津医科大学第二医院心脏科

李广平,电子信箱:tjcardiol@126.com

2014-12-11)