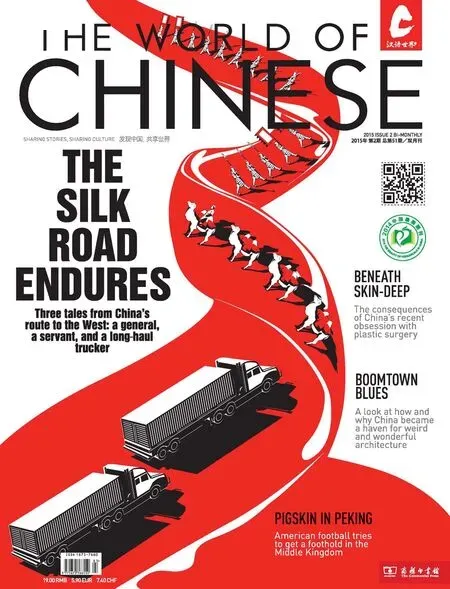

BOOMTOWN BLUES

BY DAVlD DAWSON

BOOMTOWN BLUES

HOW CHINA’S CONSTRUCTION BOOM TRANSFORMED ITS ARCHITECTURE

中国特色的奇葩建筑时代是时候告一段落了

After several years of planning, a massive workforce began constructing the Tianjin West Railway Station in early 2009. With the efforts of several thousand laborers, the vast 179,000 square-meter facility was fnished by the end of 2011. Like some of the trains that pass through on the 24 lines beneath the barrel-vault roof of the facility, the construction process was most certainly “high speed”, despite involving the relocation of the entirety of the previous train station—a historic brick German building, constructed in 1910—to a location a few hundred meters south. Construction of such a huge building at such speed would be an incredibly diffcult endeavour to coordinate in the West, but in China, it is often par for the course.

Sebastian Linack, one of the architects who worked on the design, points out that one of the aspects that made it possible was the raw size of the labor force—a workforce that would be prohibitively expensive in developed countries. He also pointed out that China’s experience constructing massive projects in recent years has meant it now has the expertise to handle projects of such magnitude.

This is one effect the construction boom has had on China’s architecture. But even as it prompts the creation of new technologies and methods of construction, it has also spawned copycat monuments, cookie-cutter neighborhoods, immense skyscrapers, scandals, corruption, and more than a few “weird buildings”.

SKY ClTY lS ONE OF MANY PROJECTS THAT HAVE SUCCUMBED TO CHlNA’S ROUGH-ANDTUMBLE APPROACH TO CONSTRUCTlON

CHlNA GOES BOOM

Sky City was meant to be the world’s tallest building. After being prefabricated on the construction site in Changsha, it was to be erected in just 90 days in 2013. The initial plan by the architects and the developer, a subsidiary of the Broad Group, suggested a 666-meter-tall building, but local government offcials, eager to have the world’s tallest building, suggested bumping it up to 838 meters, thus beating the 829-meter-tall Burj Khalifa. Offcially the project is still on the books. But aside from about a month of construction activity on the site in 2013, nothing has happened since offcials decided the project needed additional approvals. The site is now covered with water and a smattering of melon and corn crops. It would appear that Sky City is one of many projects that have succumbed to China’s rough-and-tumble approach to construction.

(From Left) A violin-shaped building in Huainan, Anhui Province; the Giant Ring in Fushun, Liaoning Province; and the Tianzi Hotel in Hebei Province

But that same approach is what bestowed fame upon the Broad Group and its founder Zhang Yue, granting them the potential mandate to revolutionize construction and architecture. The primary focus of the company is on relatively pricey air-conditioning systems that use natural gas and waste heat, which have proven popular in China due to electrical grid constraints—a natural consequence of such a rapid construction boom.

This income source has transformed Yue and the company into a ferce proponent of tougher environmental standards, which in turn spawned their subsidiary company which focuses on prefabricated buildings built at an impressive pace. In 2010, they constructed the 15-storey Ark Hotel, also in Changsha, in just six days, with the structural framework erected in less than two of those days. Admittedly, the groundwork and foundations had already been laid. But it remains an impressive achievement, particularly given the fact it used a fraction of the materials used in standard buildings and is earthquake resistant.

Perhaps this technology will help remedy the style of construction typically used for residential buildings in China, with state media acknowledging the “tremendous” waste of concrete in buildings that usually only last for 20 to 30 years, and have on rare occasions cracked or collapsed.

Higher-quality methods of rapid construction are no doubt needed, given China’s still-frenetic pace of construction, which continues on a scale far too vast for architects or policy-makers to adequately compensate.

John Van de Water, a Dutch architect with extensive experience in China, describes the approach to architecture in China using “the rule of 10×10×10”. “It’s 10 times faster, 10 times cheaper, and 10 times larger. This is very diffcult for most Western architects to understand.” He says that architecture in China “requires a different approach” and that you “have to design more strategically”. In his book, aptly-titled You Can’t Change China, China Changes You, de Water highlights various occasions where architects had to adapt their designs during the design process. “Whereas in Europe, it is more about a ‘shared information’ process, here it has a more serial basis. If requirements change, the project is changed, and the architect may not be involved with that.” He also highlighted how, in China, the clients exercise a great deal of power over the project and like to have multiple options to choose from.

The boom has affected cities in different ways. “Some frst tier cities, like Beijing and Shanghai, were already blessed with an identity. But, second and third tier cities are on a quest for identity, and sometimes their construction projects can come across as very superfcial. Their modernization process was more derived from Western ideas and less from traditional,” says Van de Water.

Sometimes these Western ideas come across in a very literal way. Entire neighborhoods have been copied from Western designs. Nearby the southern Chinese city of Huizhou lies an Austrian village. There is a Thames Town near Shanghai, and the country has more than one Times Square, with a large one on the drawing board for Tianjin. Buildings with elements copied off the White House or Capitol Hill can be found all over China. Huaxi, a village in Jiangsu Province in which wealth has soared in the last few decades, now claims to be China’s richest village. It has its own version of an Arc de Triomphe, not to mention a narrower version of the Sydney Opera House. The village hasn’t just copied from overseas, it also boasts a Tian’anmen Square.

Perhaps the most egregious example of copying, due to its sheer opulence, was the $15 million offce building of the state-owned Harbin Pharmaceutical Group, which was constructed inside and out to be a replica of the palace of Versailles, complete with gold-tinted carved walls, chandeliers, marble columns, and mahogany furniture. Seemingly oblivious to both public perceptions and rudimentary irony, the company said it was built to promote culture and showcase “social responsibility”.

But, that isn’t to say all the foreign design input has been so crudely handled; Van de Water also points out that many second tier cities are rapidly professionalizing their architecture and seeking designs that complement the local area. However, even when architects strain to integrate a project into the natural environment, it’s a diffcult path to navigate.

FORElGN lNFLUENCES

Droves of tourists visit Xiangshan, or Fragrant Mountain, each year, particularly around autumn when the red leaves are in season. Lying just to the Northwest of Beijing, it’s a popular site for residents of the capital to undertake the Chinese version of hiking, which often involves many stone steps.

Few would guess that a nearby, aging hotel was designed by Pritzker Prize-winning Chinese-American I.M. Pei (贝聿铭), who may well be the world’s most famous architect, having designed the controversial glass pyramid at the Louvre and the Kennedy Library.

But, even though his creation at Fragrant Hill, commissioned in 1978 and opened in 1982, caused a buzz when it was created, today it has fallen off the radar. This was despite a painstaking design process that was meant to integrate a range of modern styles with the Chinese setting. Care was taken to minimize the clearing of trees, resulting in a sprawling layout surrounding a Chinese garden, and 210 tons of rocks were brought in from Southwest China.

“In emotional energy, this has to be the most diffcult and the most tortuous thing I’ve ever done, because I have to deal with a system I don’t understand,” The New York Times cited him as saying at the time.

Here was a project designed by possibly the world’s foremost architect—Chinese heritage, with a world-class, international background, intending to bring cutting edge modern architecture to the East without clashing with a specifcally chosen picturesque environment—yet it’s far from being a world-renowned site.

Local limitations made it a nightmare that reportedly put intense strain on Pei and his family, not the least of which was the fact that instead of advanced construction equipment, he was supplied with a much larger number of laborers. He also had to contend with supply chain problems and unfamiliarity with the Chinese system.

Many of his quotes from 1982 resound powerfully with the troubles experienced by foreign architects operating in China today. “I had to learn a lot, not about Chinese architecture, but about Chinese history all over again, how people live and their cultural traditions, and try to see what’s still alive after the Cultural Revolution and fnd out what roots are still living and graft them on,” he told The New York Times. “I feel that all these new buildingsare rootless and will become disposable in time. What China needs, in my opinion, is again to fnd its own heritage,” he said of the Soviet-style buildings which still dominate the Chinese landscape today.

The Fang Yuan Mansion in Shenyang is shaped like an ancient coin

The height of this Soviet-style approach to construction came in 1959, with the tenth anniversary of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. As part of China’s Great Leap Forward, ten “great buildings” were commissioned, most built at a hectic pace within the frst ten months of that year. Even today, these buildings cause tourists’ jaws to drop with their sheer immensity, designed to convey the mighty power of socialism—with Chinese characteristics of course.

With China’s famous Great Hall of the People as the centerpiece, the buildings included the National Museum of China, the Worker’s Stadium, and the Beijing Railway Station. Even today, they stand as key landmarks of Beijing, projecting an aura of power.

But the boom has meant the same today; China’s architecture is represented by a different kind of monument entirely—the legions of residential high-rises, which proliferate all over the country, cropping up en masse around second tier cities where they form entire neighborhoods, often with a uniform appearance. So when buildings stand out, they often draw a lot of attention.

“WElRD BUlLDlNGS”

Dubbed the “big pants” by cheeky web users, Beijing’s 234-meter-tall CCTV headquarters was designed by Pritzker-Prize winning Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas. It was this building which drew attention from Chinese web users and media commentators when President Xi Jinping in October 2014 told a forum audience that China should not build “weird architecture”. His only guidance was that architecture should, “be like sunshine from the blue sky and the breeze in spring that will inspire minds, warm hearts, cultivate taste, and clean up undesirable work styles”.

This was hardly enough advice for architects to go on, but there have been rules imposed on construction in China. An early example was revealed in a study into the conservation of Beijing’s iconic hutong alleyways by NGO the Tibet Heritage Fund, which said that, in imperial times, the houses in the hutongs in Beijing’s central district were originally limited to just one story, because, “It was unthinkable that ordinary beings should have houses taller than the walls of the Forbidden City.”

Modern guidelines have ranged from a 2000 requirement that Beijing buildings should “mainly be grey”, as well as various attempts to rein in the construction of elaborate government buildings and limit residential developments, but these have generally been for political and economic reasons, as well as public outcries over wasteful spending. Yang Shichao, deputy director of the Guangdong Provincial Academy of Building Research, recently suggested tougher rules would be on the way but added that a building would not be deemed “weird” if it does not“consume excessive materials, if it suits the local climate, if it fts the local culture, and if it provides the necessary functions.” And make no mistake, China has plenty of“weird” buildings.

Sometimes this is because rules aren’t followed, such as the time one brazen property owner built a rock-garden and villa on top (and over the edges) of a downtown Beijing high-rise without the slightest scrap of permission. Other times the authorities themselves, in their pursuit of grandeur, commission bizarre designs or warp more ordinary projects beyond recognition. Favorite mentions of weird buildings include those such as Beijing’s Bird’s Nest stadium, and the 3.2 billion RMB “Egg” National Theater for Performing Arts, as well as the Galaxy Soho project.

However, these have plenty of supporters, which is unlikely to be the case for projects like the Tianzi Hotel in Hebei Province, which is a colorful representation of three gods and incorporates their grinning statues into the design. Representations of objects are a common theme, with the Wuliangye alcohol company creating a factory and visitor center in the shape of a bottle of its baijiu. Similarly, Guizhou’s tea museum is in the shape of a teapot. More abstract designs can be found in the shape of Guangzhou’s circle which is exactly as it sounds, with a 50-meter-wide hole in the middle.

Suzhou arguably has a building which looks far more like a pair of pants than Beijing’s much maligned CCTV headquarters, and in Suzhou’s case, the recently completed Gate to the East stands at 308 meters. Fushun, Liaoning, has a giant ring as a landmark, which lights up at night. The Fang Yuan mansion in Shenyang is shaped like a glass version of an ancient Chinese coin. The construction of the People’s Daily skyscraper in Beijing caused uproarious laughter online when it was observed it was shaped like a giant golden penis. When the construction was fnished, however, the shape gave way to a less suggestive design. All over the country, one can fnd zany monuments to the misplaced hopes of local governments that tourism will boost revenue. But whether or not the next generation of Chinese buildings will remain so eccentric, will depend in large part on the next generation of architects.

CONSTRUCTlNG CHlNA’S FUTURE

The Tsinghua School of Architecture appears from the outside to be a fairly nondescript building. It’s covered in the little white tiles that make up so many of the older academic buildings throughout the capital, and as with most buildings in the city, it is greying and turning brown around the edges of the tiles. But, rising from the open cavity behind the building, a bold, black structure emerges, a row of bamboo poking up from the wooden platforms that surround it.

“It was designed by Li Xiaodong, one of the professors here,” says Martijn de Geus, grinning. A lecturer at the university and an architect in his own right, de Geus has seen plenty of foreign architects come and go during his fve years in China and has also had a hand in training many young Chinese architects. “Many of them get a master’s degree here, then go overseas,” he says, adding that when they return to China, they are often able to make use of developed networks to launch a career.

Students can still be seen in dead of winter in the surprisingly hands-on workshops around the architecture school. Some are piecing together cardboard models, elsewhere they are using software to create designs. One enterprising student has used an advanced metal cutter to create the outline of a sword. The atmosphere is a far cry from the bookish, exam-focused stereotype which often proves to be reality in many Chinese universities, highlighting how much the architecture industry has changed in recent years.

“Five years ago, architects could come to China and experiment. They could undertake pioneering projects,”he says. “But these days, they don’t need you for that anymore.” He quickly clarifes that there is still a place for foreign architects, but their role is changing. “Now it’s more about knowledge exchanges,” he says, adding that architects are now heading into more niche areas such as airports, citing the case of the French architects involved in building an airport in the southern area of Beijing. “They have to partner with Chinese frms, and have specialist expertise.”He added that young architects can indeed come to China to gain experience, but they have to be in it for the long haul, rather than a quick tour to gain experience. This theme, that foreign architects must learn to specialize if they want to remain at the cutting edge of architecture, is echoed by many.

“These days, foreign architects try to make a strong impression,” says Samy Schneider, a German planner working in Beijing. He adds that with the increased specialization within architecture, foreign architects, consultants and planners may fnd work opportunities have expanded in certain areas. “In the past I think foreign architects were brought in for grand ideas. I think the follow up, the details, will be part of our future work.”

Schneider’s Chinese colleague, Zhang Yaming, who trained overseas, shares similar views. “Chinese local governments are getting more interested in foreign architects. If you have specialties, energy effciency for example, there is interest.”

As competition heats up, more and more architects are looking to the still booming construction industry—particularly second tier cities, where the uniform appearance of high-rise developments means architects can design on the basis of entire neighborhoods, rather than individual buildings. But they will need to compete with the next generation of Chinese architects, who are increasingly being exposed to foreign architectural ideas, such as when Koolhaas addressed audiences at the Tsinghua campus to explain his “weird building”. He also told Dezeen magazine that he believed the CCTV headquarters “articulates the position and the situation of China”.

So while the boom may be over, and the days of grand socialist monuments may have passed; China’s new crop of architects will decide the shape of China’s skylines, boom or bust.