水墨丹青 GALLERY

水墨丹青GALLERY

Sandbox Series, 2012

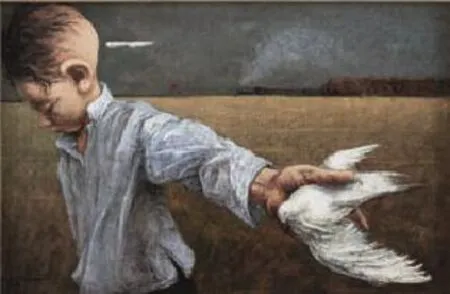

CHILDHOOD TRAUMA

Zhang Linhai’s (张林海) studio is located in Songzhuang, an oft-overlooked art zone located in a village northeast of the Sixth Ring road. His spacious studio is covered in portraits of children—a school boy sitting under a Communist leader’s portrait with his head hung on his chest, drained of all vitality; another depicts a boy playing a lost and woeful version of hide-and-seek. A half-completed painting features a boy aiming at the viewer with a slingshot, his face twisted in a queer jest. “It has a kind of cruelty that does not fit a kid,” Zhang says, smiling sadly. Unlike the hollow, listless, overduplicated faces that plague the likes of 798, the loneliness, despair, and dejection in Zhang’s portraits are powerfully evocative.

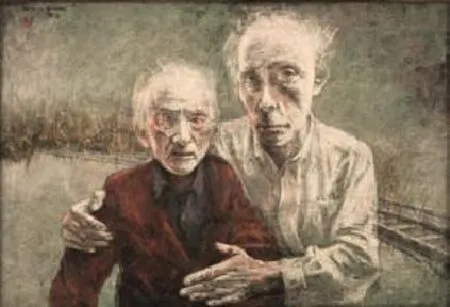

Some look at Zhang’s work and see the artist’s own childhood trauma, but speaking of this, Zhang chuckles in embarrassment. He has been asked this questionmany times before, and he always confesses that he did have a somewhat marred childhood. He was an adopted child, having gone through a disease that still affects him today, and during the Cultural Revolution he watched his father’s public torture. To some extent, that era still haunts Zhang’s works—the ideas and symbols of collectivism, zealous ideology, and Soviet-style architecture all feature heavily. Zhang describes it as “all sorts of ridiculous things that only my generation understands.”

This isn’t to say Zhang’s works are dated, far from it. Indeed, it’s hard to say what has made Zhang what he is now: his own past or the Chinese children today experiencing a childhood that is no less traumatizing. Despite being several generations apart, Zhang has a knack for accurately capturing the zeitgeist of Chinese children today, an issue that concerns him greatly.“I’m intuitively more sensitive to the situation of the lower classes and the underprivileged,” Zhang says. “Perhaps that’s why my subject is always children. The children I paint are never happy. Can you truly say Chinese children—urban or rural—are spontaneous and happy?” Zhang says. “In rural China the children are suffering from a childhood with absent parents, which is worse than poverty. The children in cities are nowhere better; they are much better off materialistically, of course; but their mentality is twisted by other things, such as so-called ‘education’. Some may ask, is this what the present generation of Chinese children are like? Think it over twice, and you will realize that, yes, this is what they really are like.”“Art is always the mirror of our times,” Zhang says. “I’m lucky that I still retain the passion for painting this subject. I may not be able to change anything, but as an artist, I can at least present a depiction of our times.”- GINGER HUANG (黄原竟)

Insights of the Past, Portraits Series No.6, 2014 (top)

Insights of the Past, Portraits Series No.1, 2014 (bottom)

IT’S HARD TO SAY WHAT HAS MADE ZHANG WHAT HE IS NOW: HIS OWN PAST OR THE CHINESE CHILDREN TODAY EXPERIENCING A CHILDHOOD THAT IS NO LESS TRAUMATIZING

Insights of the Past, Portraits Series No.5, 2014

The Earth, 2015

Happiness, 2015

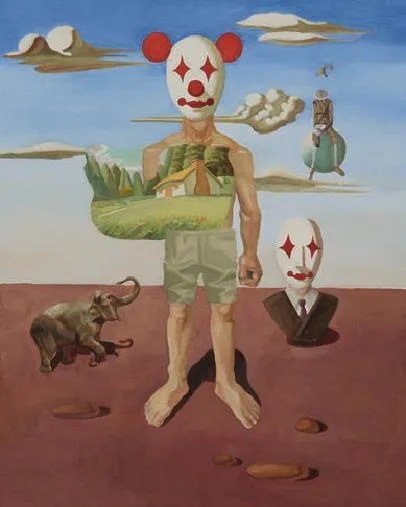

BEHIND THE MASK

What was the inspiration for this “clown” series?

Since I graduated from university, I have been exploring my own method of artistic expression, including style, form, and content. My personality is kind of introverted, so I need to look for inspiration within. I chose clowns by chance. One day I saw a clown mask and I felt its impact. The clowns represent urban people, who are perhaps nobodies in society, living on the bottom rungs. Their images are distorted, which creates an atmosphere of absurdity and ridicule. Maybe the inspiration stems from my personal experiences and feelings.

The clowns in your works are always masked. What are you trying to express?

It is a conflict between our social roles and selfconsciousness. When we enter society from school, we feel different. Living in fast-paced cities, people can all feel tense and uncomfortable. You can see that the clown images in my works follow a pattern. There are no significant individual differences. I want to show that clowns display their happiness in front of others, but behind the masks, they keep their pain to themselves. It’s a feeling of struggle and weakness. They are perplexed, isolated, and powerless.

Zhou Lei (周磊)

A post-80s generation artist, Zhou graduated from the China Academy of Art in 2009, with many of his works collected there. A Shanghai native, Zhou is active in exhibitions in Shanghai and elsewhere around the country.

Despite the curled corners of their mouths, it seems you are not trying to convey an emotion of happiness whatsoever, are you?

No, it’s not happy. Perhaps because of my personal aesthetic tastes, this series is tense, gloomy, and depressing. Their facial expressions can be interpreted as sarcasm, self-mockery, and sadness. But, the clown is sober at the same time.

Are you worried that your works might be over-interpreted?

I think the premise of over-interpretation is that viewers notice and accept your works. Then they are willing to interpret them. Art is created by the creators and the viewers together. I think there’s no need to worry about this.

How did your artistic style evolve?

It was a long process. When I was at the art academy, I focused on classical art. At that time, I didn’t like contemporary art. But it was exactly that time when Chinese contemporary art experienced a blossoming and I was influenced. I then began to try and explore. I have tried other forms of art too, like photography. But I finally I realized that my true love was painting. I think my style is derived from my heart. Of course, I was also influenced by some talented artists—like Salvador Dalí, the Spanish surrealist. I copied almost every piece of his work for practice.

What methods do you have for maintaining inspiration?

Actually, inspiration is something uncertain. I think a mature artist should guarantee that their works will always be compelling, even when they have no inspiration.– SUN JIAHUI (孙佳慧)

Violoncello,2015

Clown No.2,2014

Clown No.3,2014