Married into China

by+Xu+Linling

Joseph W. Esherick, born in 1942, is an American sinologist who has learned from three other sinologists – John King Fairbank, Joseph R. Levenson, and Frederic Evans Wakeman Jr. As one of the most outstanding scholars of contemporary Chinese history in the United States, Esherick has documented his academic findings in several books on China, including The Origins of the Boxer Uprising and Modern China: The Story of a Revolution. Not long ago, he finished another book on China, Ancestral Leaves: A Family Journey through Chinese History, but this time, he wrote from the perspective of a son-in-law of a Chinese family rather than a scholar.

A Special Summer Holiday

Every day, Esherick sips coffee in a café near Peking University in Beijing. It was there that he traced his destiny with China back to the summer holiday of 1983, when he began studying the country.

His academic mission was accompanied by a personal mission: delivering a tin of coffee to Ye Duzhuang (1914-2000), an agricultural economist at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, on behalf of Ye Wa, his Chinese classmate in the United States.

Esherick met Ye Wa when he and she were members of a team at the University of Oregon studying rural southern China.

During Eshericks first meeting with Mr. Ye, Ye Was father, the mans two other daughters continuously asked about the relationship between the visitor and their sister soon after he sat down. “Why did she ask you to send coffee home all the way from the United States?”

Their questions inspired Esherick:“Maybe she does have a crush on me,” he thought. He began to pursue Ye Wa soon after he returned home.

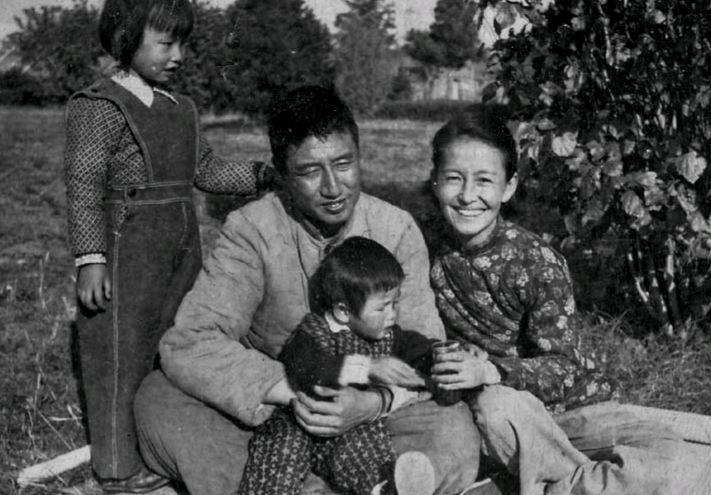

Esherick and Ye Wa were married in 1984 and traveled back to see her family again.

To mark his 30th wedding anniversary, Esherick published the Chinese version of Ancestral Leaves: A Family Journey through Chinese History in China, recounting stories of his wifes family.

A Long Journey

It took 20 years for Esherick to finish the book about a Chinese family, which was inspired by an autobiography written by Senior Ye for two of his granddaughters who long resided overseas.

Ancestral Leaves traces the life of Ye Duzhuang, a Chinese agricultural economist and translator of Charles Darwins Origin of Species : his childhood, education, love, marriage, revolutionary career, and experience in prison during the “cultural revolution.”

Memories of Ye Duzhuang also inspired his brothers, who were famous Chinese scientists and senior officials, to recall their past experiences.

Esherick and his wife began to collect stories between 1994 and 1995. They also searched their school archives from the 1930s. During the spring of 1995, they discovered the family temple in Anqing, Anhui Province in southern China, where a wellpreserved family tree was printed in 1944.

Massive data depicts a clear picture of the family of elites. The Ye family moved to Anqing during war in the 14th Century and several members passed imperial examinations during the late Qing Dynasty(1644-1911). The family witnessed a meteoric rise in the 19th Century when many members served in the royal court. One of the family-tree branches moved to Tianjin, a port city in northern China, in the early 20th Century for business. The family maintained close contact with celebrated figures, including Zeng Guofan (1811-1872), an eminent Chinese official, military general, and devout Confucian scholar, Li Hongzhang (1823-1901), a politician, general and diplomat, and Yuan Shikai (1859-1916), a Chinese general, politician and self-appointed “emperor” – an autocratic head as the first President of the Republic of China (1912-1949).

During the 1930s, five boys from the Ye family studied in succession at Nankai Middle School, a famous modern-style school in Tianjin. Later, they studied at Tsinghua University and Yenching University, the top institutes of higher learning in China. They set off on different journeys after the outbreak of the war against Japanese aggression.

Esherick drew vivid pictures of the family members as they navigated the ups and downs of Chinese history. “Its all about my concern for the social and political history of China,” he explains. “The difference is that I illustrated it another way. What I tried to interpret is the interaction between historical megatrends of social movements and revolutions and a family – an essential institution of society– as well as the evolution of the function, structure and significance of the family during a long historic journey.”

Miss Tomato

Ye Wa handled interviews dictated by her family members, while Esherick made recordings, took notes, and raised questions for further interviews.

“We amassed over 100 hours of dicta- tions on my recorder,” Esherick reveals. “I focused on details with questions like ‘What did you wear? ‘What did you eat? ‘Did you go to the movie? or ‘How did you go to school? Such seemingly minute details help make a life story richer and fuller.”

On a hot summer day in the 1930s, a college girl gave a fresh tomato to Ye Duzheng, who was then studying at Tsinghua University, luring him towards “Pioneer,” a left-wing student organization at the school. He joined 200 students from Beiping (Beijing today) to participate in a military training in Shanxi Province during the 1936-37 winter holiday, just before the Japanese invasion of northern China.

Sixty years later, a brother-in-law asked Ye why he chose to join Pioneer. Now a famous Chinese atmospheric physicist and former vice president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, he admitted, “A girl I liked was a member.” Miss Tomato was a hard leftist. To win her favor, the top student at Chinas top institute of higher learning threw himself into a political movement in which he had little interest.

In 1938, the couple returned to Shanxi with the Pioneer group. Before long, she left him. “I met someone else, a revolutionary,”she said upon breaking up. “You want to be a scientist, but I want to be a revolutionary.”

This development left him devastated for quite a long time. He left Pioneer for Xian in Shaanxi Province, and then for Kunming in Yunnan Province. He abandoned his political career in favor of academics when Southwest Associated University was founded. He traveled to the University of Chicago for further study and returned to China in 1949, specializing in aerophysics and became one of the top atmospheric physicists in the country.

Esherick doesnt recall how he dug up details about the fresh tomato, but “it was something he could never forget.”

“I had no angle to push,” Esherick grinned. “I wanted to figure out the reasons behind his participation in the movement– the motivation. The person I interviewed could hardly recall the reasons, but then the picture becomes clear with the help of such details.”

“A good question a historian often asks is ‘Why?,” asserts Esherick. All political movements, including the Boxers and the Revolution of 1911, are the outcome of social situations. So is true for individuals.“Peoples political choices are usually actually personal. You have to dig deeper to find the real reasons and motivations.”