Wang Tiantian:A Different Story to Tell from Previous Generations

By+JON+BURRIS

GIVEN my familys background, it was inevitable that I would become an artist,” Wang Tiantian told me, standing in her studio surrounded by canvases that bear little resemblance to the works of her father, artist Wang Huaiqing.

Raw talent runs deep in her family – her grandparents were artists – but Wang Tiantian emphasizes the difference between generations. “There are 25 years between the year my father graduated and started work and when I graduated in 1997, during which time many new things entered China. Ive never tried to avoid his influence; I simply have a different story to tell.”

To appreciate just how different Wang Tiantians work is from her fathers, and how far she has come as an artist over the last 15 years, I have to think back to when we first met in 1995.

As an independent curator, I had arranged to visit her father to interview him about paintings owned by a private collector that I represented. Tiantian, her mother Qinghui, and Huaiqing shared a small four-room apartment in central Beijing. One of the rooms was clearly devoted to art produced by all three family members. I remember seeing Tiantians drawings, mostly figure studies. They were good, fairly traditional, and noticeably different from those in her fathers works. His figure studies, predominantly nudes, bordered on the abstract and had a definitive style.

Tiantian explained that the difference was attributable to her pictures being class assignments at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, where teachers expected young artists to be able to draw realistically, regardless of what they chose to do in the future. Ive always thought that this is one of the main differences between our educational systems, East vs. West.

In the West, students are encouraged to be“original” at the expense of learning basic rules of art and experimenting with comparative techniques. No one who has ever studied Picassos early work would disagree that he was a superb drafts-man. And, in my opinion, no young artists today should be able to get through school without being required to study the work of such masters.

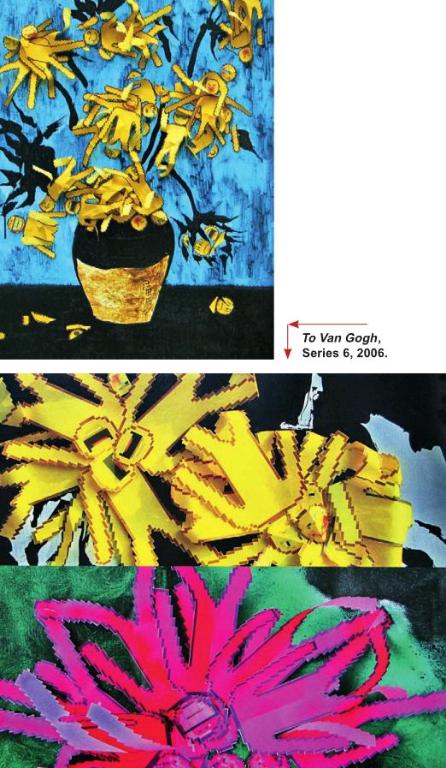

Wang appreciates this, and is utilizing what she has studied for her reinterpretation of art, from Fin de siècle works such as those of Van Gogh and Monet to classical works from the Song Dynasty (960-1279). As we discussed her most recent paintings, one of them a large triptych, multi-media version of one of Monets waterlilies, I asked her how she arrived at this theme.

“When I began college, first in Beijing and later in New York, I had a strong interest in literature, but found that I was best at producing art. For me, it was easy to make figurative drawings or paintings, but as I think artists need to continuously challenge themselves I began referencing the history of art when deciding what I would do next. New media has invaded everyones life. Everything digital has a strong influence on young artists who have basically abandoned realism and traditional mediums. You might say my generation has a language discrete from traditional art, so we incorporate what we know. Looking at one of my new paintings from the To Monet series, you can immediately identify Monet. But as you get closer, you see that the waterlily is actually composed of a group of three-dimensional figures, almost cartoon-like, and with the pixilated edges you might see on an image blown up on a computer screen. In my To the Song Master Life Drawing Treasure Birds series I have created more stylized birds from a classical brush painting and have attached physical objects – gold leaves – to the canvas. Its a fusion. I think fusion is good because, as with food, a blend of traditional Chinese and international dishes is more interesting, and reminds us that we can tire of things always being the same.”