Extending the Distributional Bias Hypothesis to the Acquisition ofHonorific Morphology in L2 Korean

JEANSUE MUELLER

University of Maryland, USA

ExtendingtheDistributionalBiasHypothesistotheAcquisitionofHonorificMorphologyinL2Korean

JEANSUE MUELLER

University of Maryland, USA

Korean verbs can be marked with both referent and addressee honorific morphology. An analysis of a teledrama corpus and a phone call corpus shows that these two morphological classes co-occur in a biased distribution indicating an association between the two classes. An experiment was conducted to determine whether Korean heritage speakers’ acquisition of Korean was affected by this association as would be predicted by the distributional bias hypothesis. Twenty heritage learners of Korean performed a teledrama oral translation task which elicited two addressee honorific styles with and without referent honorific marking. A repeated measures ANOVA on the four possible addressee-referent honorific combination showed differences in performance. A post hoc analysis of pairwise contrasts indicated that performance was superior on the referent honorific (RH) plus hayyo addressee honorific (AH) combination relative to the RH plus hay AH combination. This result is incompatible with an account that explains acquisition in terms of the cumulative frequencies of the forms in input. It is also incompatible with accounts claiming that learners do not associate the forms during the acquisitional process. It is argued that the distributional bias hypothesis best accounts for the pattern of results and the frequency-driven conflation of semantically related concatenated affixes may have special significance for agglutinative languages such as Korean.

referent and addressee honorific morphology, distributional bias hypothesis, addressee-referent honorific combination, concatenated affixes

Korean has a highly elaborate system of honorifics; hence, it comes as no surprise that L2 learners encounter protracted difficulties as they attempt to untangle the semantic contribution of multiple lexical and morphological honorific structures that occur simultaneously in typical input. The learner’s task is rendered even more complex by a wide range of factors, to include cultural differences in the importance attached to power and distance (Byon, 2005), deviations from typical usage to mark strategic style shift (e.g., anger) or long-term shifts in relationships (Brown, 2008b; Mueller & Mueller, 2009), variation in discourse due to factors unassociated with honorification such as information status (Eun & Strauss, 2004; Strauss & Eun, 2005), generational shifts in the role of honorification due to social change (Kim-Renaud, 2001), the effects of limited exposure to authentic input, and the failure of textbooks to provide access to the full range of social situations that give rise to typical patterns of honorification (Brown, 2008a).

Due to such factors, Korean learners, rather than mastering the system all at once, are more likely to pass through a series of non-target like stages as they progress toward more native-like grammars. The present research tested the hypothesis that these intermediary stages, rather than constituting random deviations from target-like use, represent a systematic conflation of honorific morphology and that this conflation is driven by learners’ sensitivity to the frequency of honorification patterns in the input.

LITERATURE REVIEW

As learners acquire a second language, form-meaning mapping is likely to be affected both by developmental constraints (Pienemann, 1998) and L1 transfer (Wode, 1983). In addition, learners may at times develop non-target like mappings based on spurious correlations in the L2. Such correlations have been proposed by Andersen (1990, 1993) as a possible explanation for learners’ tendency to associate aspectual verbal morphology with specific lexical classes of verbs. A number of studies (e.g., Ayoun & Salaberry, 2008; Bardovi-Harlig & Bergström, 1996; Robison, 1995a; Shirai & Kurono, 1998) have demonstrated that learners tend to first use progressive morphology with activity verb frames such asrunorwatchTV(i.e., activities with no inherent end-point) and tend to first use perfective morphology with accomplishment (e.g.,eatanapple) or achievement (e.g.,droptheball) verb frames, which are telic and thus imply an inherent end point (For a review, see Bardovi-Harlig, 2000).

To explain this pattern, Andersen (1990, p. 58) proposed the distributional bias hypothesis (DBH) as follows:

There are... properties of the input that promote the incorporation of an inappropriate form-meaning relationship into the interlanguage. That is, the learner misperceives the meaning and distribution of a particular form that he discovers in the input, following the Distributional Bias Principle: If both X and Y can occur in the same environments A and B, but a bias in the distribution of X and Y makes it appear that X only occurs in environment A and Y only occurs in environment B, when you acquire X and Y, restrict X to environment A and Y to environment B.

In other words, learners are highly sensitive to distributional patterns in the input and gravitate toward form-meaning connections that are consistent with these distributions even when these form-meaning connections diverge from the L2 grammar. Andersen’s definition of the DBH seems to have been formulated to specifically apply to the aspect hypothesis as it has been applied to English. The “X” and “Y” in the formulation readily call to mind past tense and progressive marking and the categories of lexical aspect (e.g., telic and atelic verb frames). However, the aspect hypothesis has been researched using data from a wide range of languages, many of which do not include two types of relevant morphological marking. Even when examining the occurrence of a single morphological form within multiple contexts, the DBH has often been cited as an explanation. For this reason, the DBH, as used in this study, will be formulated more broadly to include: (1) the association of one form with one of two or more contexts (X with context A versus context B), and/or the association of one of two forms within a given context (X but not Y with context A). In other words, the DBH can be formulated as a situation in which observation of language use shows that the observed distribution of a form within linguistic categories diverges significantly from what would be expected if the linguistic form(s) and linguistic category or categories were unassociated. Statistically, the DBH (as thus formulated) would imply the occurrence or nonoccurrence of at least one categorical variable (e.g., a morphological form) in association (positive or negative) with the occurrence or nonoccurrence of another categorical variable (e.g., a linguistic context or the occurrence or nonoccurrence of another morphological form).

The DBH can account for the widespread finding that L2 learners tend to conflate lexical and grammatical aspect. Yet research on the L2 acquisition of aspect has been unable to arrive at a definitive endorsement or rejection of the hypothesis. The current study provides additional confirmation of the DBH by testing whether the hypothesis can be used to predict learners’ conflation of L2 categories in a different area of grammar. Specifically, the study examined whether learners are led astray by the distributional bias associated with referent honorifics (RH) and addressee honorifics (AH) in Korean.

This paper empirically establishes the existence of the bias in the production of L1 speakers by means of an analysis of two Korean spoken corpora. It then reports a study conducted using a task in which participants translate dialogues designed so that both RH and AH must be taken into account as discrete grammatical categories. A control group of native speakers (NSs) also performed the task to establish its validity.

It should be noted that whereas the DBH was originally used by Andersen to explain the conflation of lexical and grammatical aspect, the proposed study extends the DBH to explain conflation of two morphological forms. In a sense, this constitutes a stronger (and thus more falsifiable) theoretical position as it means that the hypothesis can explain a wider range of grammatical phenomena.

In addition to psycholinguistic plausibility, the DBH in this case would be consistent with the subset principle, a principle of learning theory by which “learners always make the minimal assumptions about the language they are acquiring which they extend, instead of the maximal assumptions which they restrict” (Johnson & Johnson, 1998, p. 311). An L2 grammar that conflates RH and AH is more parsimonious and should thereby be easier to acquire than the target grammar, which distinguishes the two categories.

The hypotheses put forth in the study are also consistent with a prototype account. It could be that learners initially conflate RH and AH due to the fact that both target forms are associated with a prototypical notion of honorification. As the proposed study is unable to distinguish between prototypes and distributional bias as mechanisms underlying the hypothesized effect, no attempt will be made to differentiate them in the analysis. It will merely be noted that prototype effects and the DBH are likely to have synergistic effects. In other words, the effect of the distributional bias on NNSs’ interlanguage is probably enabled by the similarity in meaning between the two conflated grammatical categories.

KOREAN HONORIFICS

Korean honorifics, viewed broadly, serve to place both the referent and the addressee on the axes of power and solidarity relative to the speaker (Kim-Renaud, 1986). Korean is a language that stands out in cross-linguistic comparisons as particularly rich in honorific forms, which can appear as: (1) a nominal suffix, (2) a specific honorific form of a noun, (3) an honorific case particle marking, for example, the nominative or dative case, (4) an honorific marker on a verb, or (5) a special honorific form of a verb.

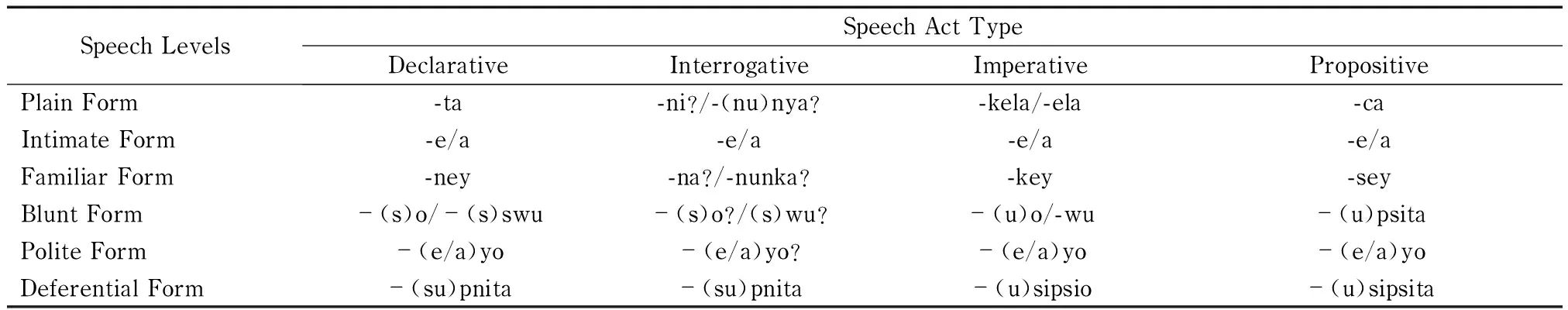

Korean honorifics are associated with specific registers, which researchers divide into various speech levels based on addressee honorifics. These forms are determined by the relationship between interlocutors. Sohn’s (1999) schema, which lists six levels, is widely used, although some researchers (e.g., Kim-Renaud, 1986) have argued that there are actually more speech levels. Each speech level has its own unique set of verb endings which are used to indicate the level of formality of a situation. Because the three most informal levels of Sohn’s classification are used relatively infrequently, they will not be considered in the current study.

Another key feature of Korean honorific system is the honorific morpheme (u)si(the short vowel—u- is inserted when preceded by a consonant), which is affixed after the verb stem and occurs prior to other verbal morphology. Sohn (1999) refers to this marking assubjectreferenthonorification (as opposed toaddresseehonorification) as it elevates the social status of a human referent related to the grammatical subject of the clause with respect to the hearer. The following sentence provides an example of multiple honorific forms as they occur within a single simple sentence.

Sensayng-nim-kkeyseka-si-ess-e

Teacher+Honorific+Honorific-Nominative go+(RH) (u)si+Past+Intimate Form (AH)

“The teacher went [i.e., left].”

Here, the -nimsuffix has been added to show respect to the teacher along with the fairly marked honorific nominative marker -kkeyse. Likewise, the verb is marked with the RH affix (u)sito show the speaker’s deference toward the subject of the verb, which is the teacher. The verb-final affix -eis an intimate AH form, indicating that the addressee, relative to the speaker, is of similar age or status (or perhaps is younger or of lower status).

METHOD

A corpus was constructed and analyzed to demonstrate the suitability of the theoretical framework of the study (i.e., the DBH). The study then tested the hypothesis that learners conflate the two types of honorifics using an experimental task involving the oral translation of scenes from a Korean teledrama.

Corpusanalysis

This study sought evidence that AH and RH marking tend to occur in a lopsided distribution. AH forms are typically unaffected by the status of the subject. However, a distributional bias is likely due to the frequent use of second person in discourse. When the subject of a verb (i.e., the referent) and the addressee happen to be the same person, RH and AH will tend to converge, as they are determined by similar considerations. Such convergence is likely to produce a noticeable bias in the overall distribution of the forms as they occur in combination in the input.

To empirically establish that this bias in fact exists, two small corpora were compiled and analyzed. The first corpus consisted of a random selection of texts from the Korean Call Home Corpus produced by the Linguistic Data Consortium. This corpus consists of authentic phone conversations of Korean native speakers in the U.S. who gave permission to have a phone call to Korea recorded.

The second corpus consisted of 13 scripts taken from Korean teledramas. These teledramas, which tend to comprise about two- or three-dozen episodes, were used as they provide speech samples from a wide range of situations. The corpus consisted of several thrillers (e.g., spy and intrigue stories), several romances (often involving extensive interactions with the key figures’ families and workplace peers), family-based stories, a comedy, and several teledramas based on specific themes such as the Korean Olympics and an amateur classical music orchestra. Table 1 shows the composition of the Korean Teledrama Corpus.

Table 1 The Composition of the Korean Teledrama Corpus

The Call Home Corpus consisted of authentic native discourse of speakers engaged in phone conversations. The conversations were already transcribed and were therefore easy to compile and analyze. Unfortunately, the context of a phone conversation was limited as the discourse almost always occurred between only two people who tended to use consistent speech styles and honorific forms throughout much of the conversations. The corpus was therefore used primarily as authentic data confirming the trends observed in the Korean Teledrama Corpus.

The Korean teledramas provide a much richer source of verbal interactions within diverse contexts. It might be argued that these dialogues are inauthentic and possibly diverge in minor ways from authentic discourse (Quaglio, 2009). Even so, Korean native speakers’ acceptance of the speech in these teledramas as realistic and natural would suggest that they are largely representative of everyday discourse. Ideally, authentic recordings of people engaged in similar situations would be analyzed, but authentic discourse of the wide range of interactions shown in teledramas (e.g., emotional outburst, meetings between multiple interlocutors of different ages, intimate discussions, and so on) are unlikely to be recorded due to concerns for participants’ privacy, and if recorded, are likely to be affected by participants’ awareness of being recorded.

Formal written texts were excluded from the analysis, due to the tendency to use either a neutral style (with conventionally fixed endings with little or no variation) or consistent use of deferential form. For these texts, the RH may vary but the AH forms, which address the idealized reader, are almost always consistent. When dealing with most abstract topics in an impersonal manner, even the RH is seldom used, due primarily to the nature of the content, so formal written texts that are likely to be encountered by the L2 learner are unlikely to be useful in their acquisition of the distinctions that govern the appropriate use of RH and AH.

The two corpora were analyzed by coding the presence or absence of the RH and AH types (See Table 2). Sentence-internal verbs were excluded, as these lack addressee honorification. Korean also has many sentence-final endings that do not allow for the full range of AH and only take the softener—yo. Many of these are historically derived from suffixes connecting an initial clause to a succeeding clause, but as speakers often dropped the implied succeeding clauses, these suffixes became conventionalized as sentence-final affixes. These were also excluded from the analysis as the status of these sentences within the paradigm of addressee honorification is unclear. Levels of addressee honorification interact with speech act types, forming the paradigm depicted in Table 2.

Table 2 Addressee Honorific Styles as They Appear in Sentence-final Verbal Suffixes

As the frequency of Korean honorification varies considerably according to the type of interactions within a given segment of discourse, the two corpora, even when used in combination, cannot provide a precise picture of the distribution of the two types of honorifics. Even so, they should be sufficient to demonstrate the general patterns of interaction between the two honorific types in the input. Both intuitively and based on logical inference, the distributional bias should be substantial. After all, everyday speech is likely to involve numerous instances in which the person being addressed is also the subject of the verb. Virtually all such instances would entail correspondence between referent and addressee honorification. Because the distributional bias is likely to be large, the corpus analysis should be able to detect the bias even if the measures lack a high degree of sensitivity.

ResultsofCorpusAnalysis

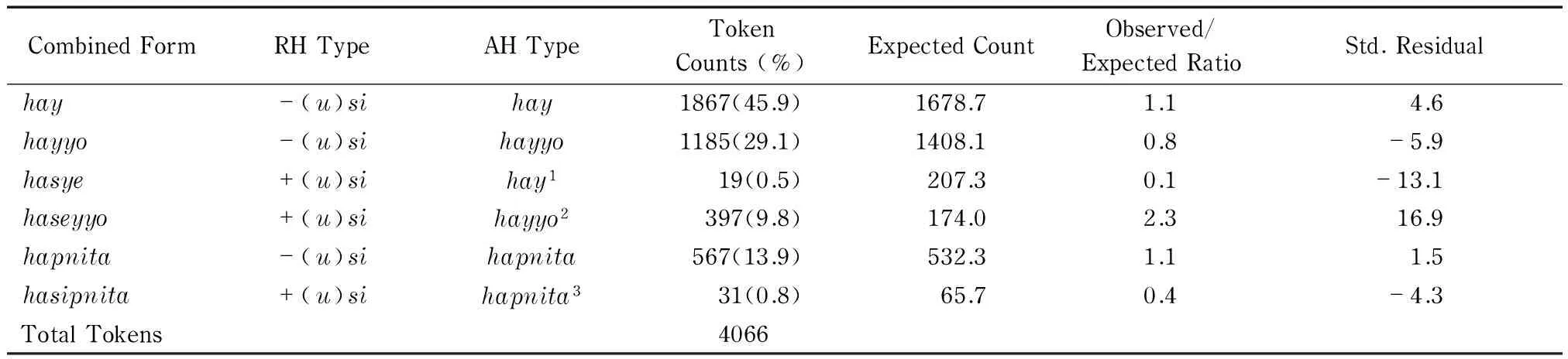

The frequency of occurrence of the RH and AH forms in the Korean teledrama corpus was analyzed using a chi square analysis, which was used to measure whether there is an association between the RH and AH. Table 3 displays the results of the token analyses in the distribution of RH and AH morphology in the Korean teledrama corpus.

Korea is an SOV language with rigid adherence to the rule that sentences end with a verb. The RH and AH morphemes are both suffixes. The RH marking, +(u)si, can appear on both sentence-internal and sentence-final verbs. On the final verb, it appears in combination with the AH marking, which appears as the final verbal affix in a string of verbal affixes.

The AH affixes appear on sentence-final verbs. Because AH forms are suffixes with onsets that can change slightly as the result of vowel harmony and other factors, the proposed study will follow the convention (adopted solely for purposes of explication) of referring to the AH forms using the verbal paradigm associated with the verbhata(to do). The paradigm for other verbs is identical except for minor changes due to vowel harmony and minor changes in the realization of the forms due to phonotactic constraints. For example, the intimate form with RH marking will be referred to ashasye, denoting the verb stem forhay(verbdo)+(u)si(RH marking) with the intimate AH ending -e.

As a whole, the Korean Teledrama Corpus yielded 4,068 tokens of sentence-final verbs. The results have been presented in tabular form with the expected count, observed count, percentages, and standardized residuals (See Table 3). Statistically, the expected count is the number of tokens one would expect if AH and RH markings were independent. The standardized residuals are the error between the expected frequency and the observed frequency standardized as a z-score.

Table 3 Distribution of Referent and Addressee Morphology in Korean Teledrama Corpus

χ2(2,N=4066)=534.3,p<0.001

A general observation based on Table 3 is that+RH occurs with much less frequency than the polite forms of the AH (thehayyoandhapnitaAH style). This is to be expected in light of the fact that referent honorifics necessarily occur with verbs or verbal patterns that have a human referent, whereas addressee honorifics can be used on any verb as they merely index the status of the addressee.

When examined in terms of their occurrence in combination, it was found thathayyo+(u)sioutnumbershay+(u)si, and the percentage figures indicate thathayyois skewed in favor of +(u)si. The standardized residual of all AH types excepthapnitawere significant. In particular, the distribution ofhayyo+(u)siandhay+(u)sidiverged sharply from their expected distributions, (Z=17.2;Z=-13.0). This indicates thathayyo+(u)sioccurs more than would be expected if RH and AH forms had no association. In contrast,hay+(u)siis negatively biased, indicating thathay+(u)sioccurs less than expected.

The standardized residuals indicate that the association between RH and AH is mainly driven byhayyo+(u)siandhay+(u)si. The calculatedχ2value with two degrees of freedom at the significance level atp<0.001 is 534.3, greatly exceeding the critical value. Therefore, the null hypothesis can be rejected at an alpha level ofp<0.001, indicating that the RH and AH are not independent but rather are associated.

The deferential form of AH (e.g.,hapnita) showed less association with RH marking. The deferential form is highly formal and tends to be used less within casual conversation. Contrary to what might be expected, this form tends to occur less frequently with RH honorifics (31 tokens) than would be expected (65.7 tokens) if the two forms were independent. Although a full exploration of this association is beyond the scope of this experiment, some observations may point to a possible explanation. An analysis of thehapnitatokens (i.e., tokens of the deferential form without RH marking) found that many of the sentences were first person. It may be that the extra deference implied by the form is often deemed necessary by younger speakers when making a statement regarding their own personal intentions to an elder or to a person in a socially superior position. In other words, statement of intended action may be regarded as face-threatening and may therefore invoke the need for a show of greater deference.

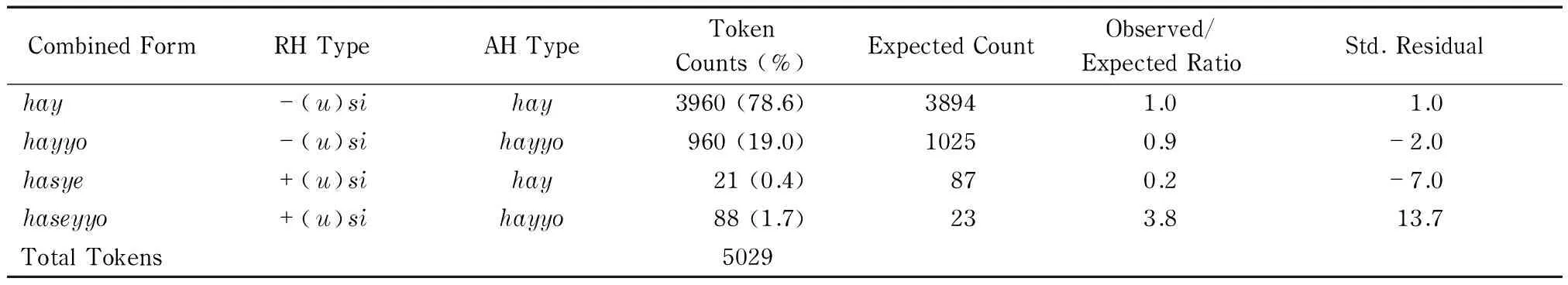

The Call Home Corpus yielded only 11 tokens of the deferential form (i.e.,hapnita), only one of which include the use of RH marking; consequently, chi square values could not be calculated when these forms were included due to the small expected cell frequencies which were less than five for one cell. These results reflect features of the corpus compilation; participants were likely to call people they knew well and were thus less likely to employ the deferential form. Even so, it may be noted that the ratio between tokens ofhapnitawithout RH and tokens with RH exactly matched the ratio found in the teledrama corpus. The results are provided in Table 4.

Table 4 Distribution of Referent and Addressee Morphology Combinations in Call Home Corpus

χ2(2,N=5029)=242.2, p<0.001

As it shows, there was a significant association between RH and AH,χ2(1, N=5029)=242.2,p<0.001 (two-tailed). The standardized residuals for bothhayyo+(u)siandhay+(u)siwere significant. Compared to the teledrama data, the gap between the values ofhayyo+(u)siandhay+(u)siwas much greater,Z=13.7;Z=-7.0. Overall, the results resemble those of the teledrama corpus:hayyo+(u)siandhay+(u)sicontribute most to the association of RH and AH with the former combination exhibiting a positive association and the latter combination exhibiting a negative association. The phone corpus data thus confirm the results of the teledrama data, but represent only a narrow range of everyday speech as they are mostly limited to speech between familiar interlocutors.

It should also be noted that the use of the RH (u)siwith thehayaddressee style in both the Teledrama and Call Home Corpus accounts for about 4.3% and 19% respectively of the total use of (u)siamong sentences using the (u)siaffix. These proportions are comparable with the general range of aspect-related phenomena investigated in research on L2 learners’ acquisition of aspect (i.e., grammatical and lexical aspect). Robison (1995b), for example, found that progressive grammatical aspect (~ing) occurred with only 9% of achievement verbs, while ~ingoccurred in only 2.6% of states. On the other hand, Robison found low chi-square values key contrasts when analyzing the observed/expected ratio. In this light, it may be argued that Korean provides a clearer test-case for the DBH, as the Korean RH and AH show more marked contrasts in their observed versus expected ratios (and thus show clearly significant chi-squared values). Moreover, unlike some combinations (e.g., the use of ~ingwith stative verbs), there is nothing inherently odd about using all RH and AH combinations. The low frequency of certain combinations of RH and AH is simply an epiphenomenon which is mostly likely related to the frequency of certain situations within discourse.

HYPOTHESES

It must be kept in mind that referent and addressee honorific forms, like lexical and grammatical aspect, are independent in native Korean grammars (as confirmed by native speakers’ use of these forms, based on independent criteria). The claim to be tested in the proposed study is that (1) nonnative Korean grammars conflate these forms, and (2) this conflation coincides with distributional frequencies of the combined RH/AH forms. In other words, NNSs are learning the forms based on co-occurrence frequencies in the input. The study will focus exclusively on DBH predictions related to the intimate (e.g.,hay) and polite (e.g.,hayyo) AH forms. The deferential form will be excluded for two reasons: (1) the form has less skewing in its distribution; hence, the frequency of its use in combination with RH marking is less likely to affect patterns of acquisition; and (2) the form is slightly more difficult to elicit using the methodology adopted in the proposed experiments, due to the possibility of using polite forms in its place in all but the most formal of circumstances.

The relevant hypothesis in the proposed study could be stated as follows:

H1: NNSs performance on RH and AH reflects their sensitivity to the frequency of these formsastheyoccurincombination. In terms of the chi square distributions, this sensitivity will thus reflect the observed frequencies of the four RH and AH combinations rather than the expected frequencies. As a result, participants will perform best on the most frequently occurring combinations, that is, the (-) RH intimate AH category, followed by the (-) RH polite AH category, which will, in turn, be followed by the (+) RH polite category. Performance will be the worst on the (+) RH intimate AH category. Using the verbhata(i.e., do) for purposes of explication, H1 would thus predict performance as follows:hay>hayyo>haseyyo>hasye.

The research will thus reject the following alternative hypotheses.

H2: NNSs’ knowledge of both RH and AH is based on separate representations of these forms, and the two categories are thus learned independently. Participants’ performance will therefore reflect sensitivity to the independent frequency of RH and AH. If this is true, their performance should mirror the expected frequency count in the chi square analysis. Performance should thus be best on the (-) RH intimate AH category, followed by the (-) RH polite AH category, which will, in turn, be followed by (+) RH intimate AH category. Performance should be worst on the (+) RH polite AH category, as this category is a combination of the least frequently occurring RH and the least frequently occurring AH. Using the verb do (hata), H1 would thus predict performance as follows:hay>hayyo>hasye>haseyyo.

H3: NNSs’ knowledge of both RH and AH or their knowledge of either one of these categories is not affected by the frequency of these forms in the input. If learners acquirehay, the+RH intimate AH category, andhayo, (+) RH polite AH category, contrast and then begin to acquire the RH forms, their accuracy on the RH forms should parallel their accuracy when usinghayandhayyowithout RH marking. In other words, their knowledge of the combined forms should be equivalent to their rate of accuracy on a given AH form multiplied by the rate of accuracy on the RH form. If H3 is correct, an accuracy order ofhay>hayyo>haseyyo>hasyeas well as the orderhayyo>hay>hasye>haseyyoshould not occur.

It should be noted that H1 and H2 make similar predictions regarding participants’ performance on the (-) RH categories. The key focus of the study will therefore be on the opposing predictions regarding the (+) RH categories.

Participants

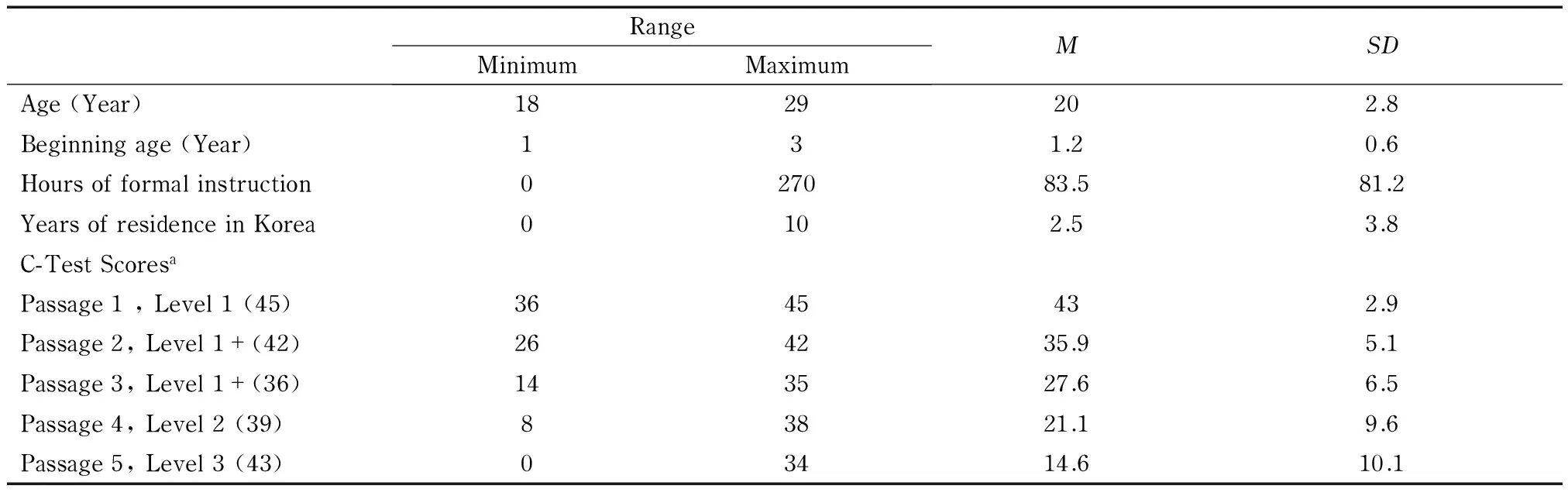

Twenty NNSs and 20 NSs of Korean were recruited. NNSs were asked if they knew enough Korean to understand and translate a Korean teledrama’s English script back into Korean. NSs were asked if their English was sufficient to understand an English script version of a Korean drama and translate it. During the recruitment, participants were engaged in 10 to 15 minutes of conversation to confirm that they possessed adequate knowledge of Korean. Participants who demonstrated no knowledge of either RH or AH marking during the task (i.e., their use of both classes of honorific morphology never varied) were excluded from the study and replaced. Moreover, because the focus of the experiment was on the interlanguage development of Korean honorific morphology, participants who showed native-like use of both classes of honorific morphology were excluded. As shown in Table 5, the NNSs tended to be young adult heritage speakers who varied in their level of formal education. The proficiency of the NNS group was measured by using the Korean C-Test (Lee-Ellis, 2009), which was developed with the specifics of Korean language structure in mind. The test uses Interagency Language Roundtable (ILR) skill-level descriptions in passage selection to test a wide range of NNS of Korean participants’ proficiency levels. Based on the results, the NNSs can be described as possessing fairly advanced proficiency on the ACTFL ILR (Interagency Roundtable) Scale.

Table 5 Nonnative Participants’ Background Information and C-test Scores (N=20)

aThe maximum possible scores for each level are in parentheses.

MaterialsandProcedure

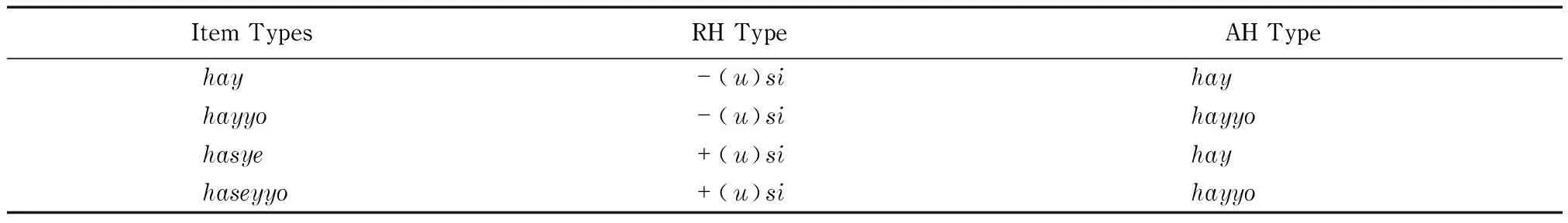

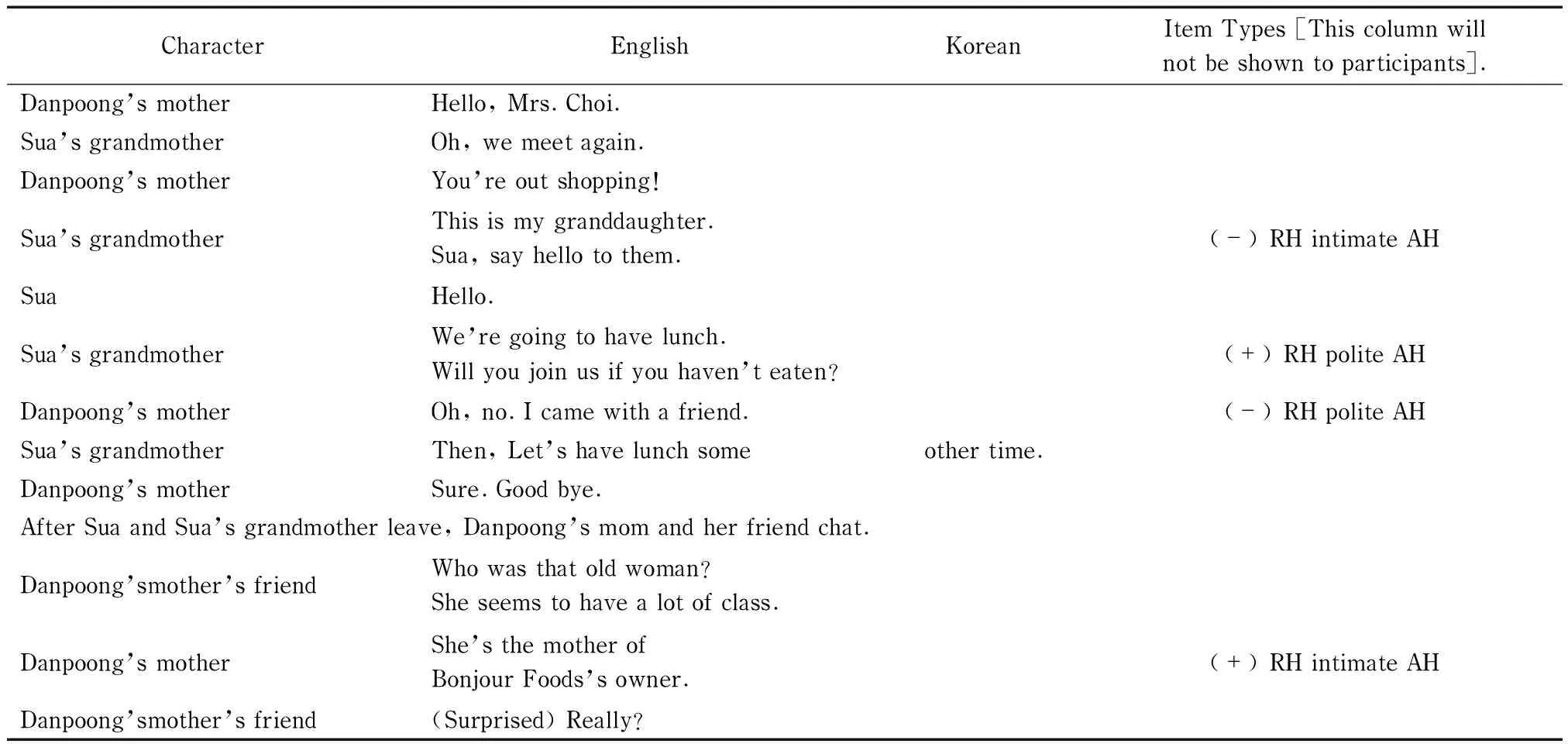

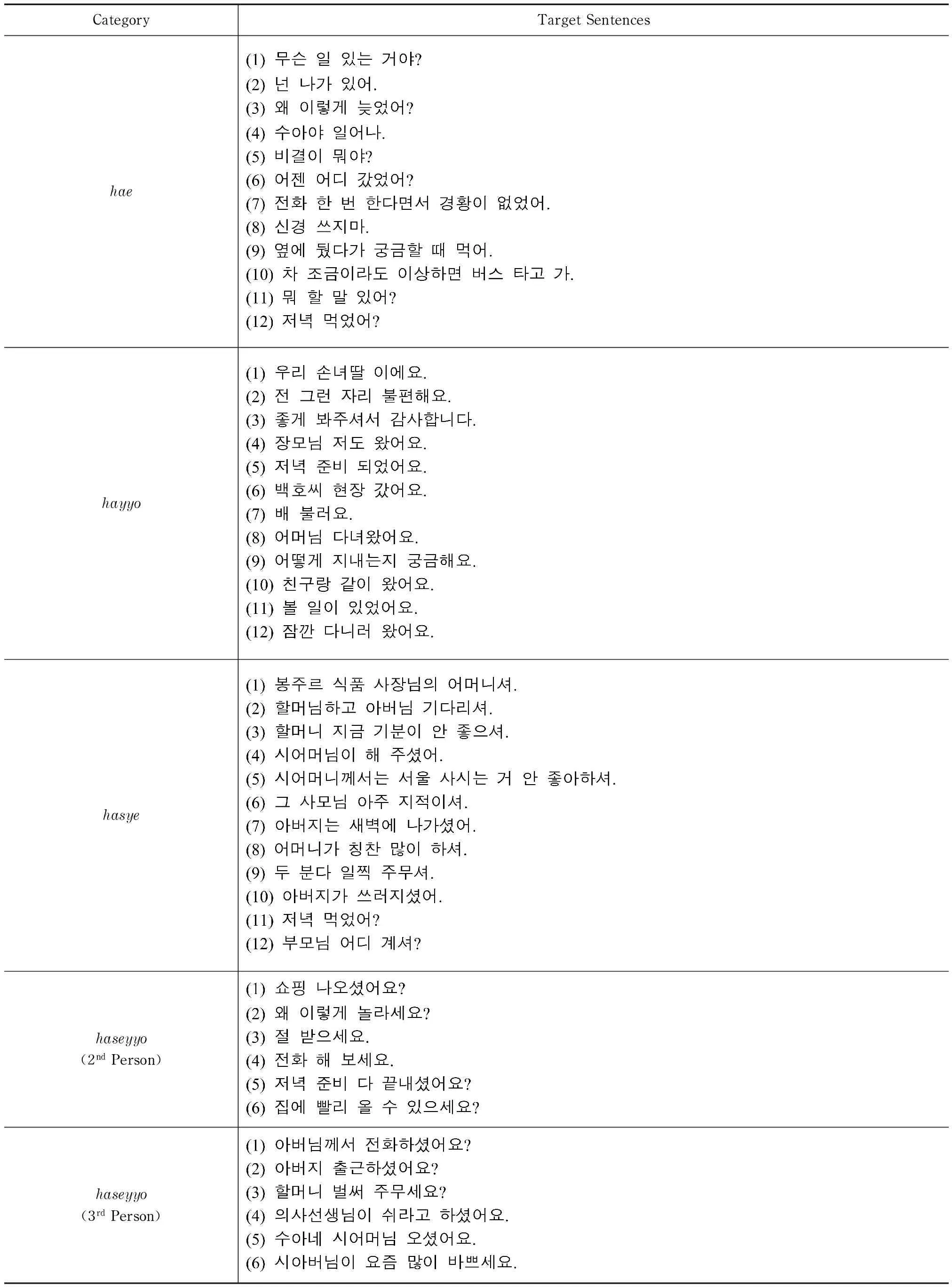

Data were elicited from participants using oral production elicited via an English to Korean dialogue translation task consisting of fifteen translated script segments directly taken from a Korean teledrama (LikableorNotfrom KBS TV). The task included 48 target items (12 items for each of the categories:hay-(u)si,hayyo-(u)si,hay+(u)si,andhayyo+(u)si. These are shown in Table 6. Cronbach’s alpha for the test items based on the NNS group’s scores was 0.876. This estimate suggests that the translation task used with this population has adequate internal consistency. To allow for post hoc analysis of the role of person, test items that involved the use of both RH and AH were split into six items in which the verbal referent was second person and six items in which it was third person. Care was taken to select target situations for the polite AH form in which the deferential form was clearly implausible as an alternative.

Table 6 Four Item Types

Prior to participants’ performance of the task, the characters and background for the segments was explained using a PowerPoint picture of the figures in the cast. The PowerPoint introduction for each of the 15 segments included a brief overview of the situation and the relationship of each character followed by the target dialogue in English. Participants then viewed a picture of the scene on PowerPoint and reviewed key vocabulary. The vocabulary included all low-frequency lexical items that were unlikely to be readily retrievable by Korean learners at the participants’ level of proficiency. Participants were then asked to go back through the dialogue script, this time producing each character’s utterance in Korean. On the PowerPoint, call out icons (i.e., the balloon-shaped icons that appear above characters in comic strips) appeared above each character whose turn it was to speak, so as to remind participants of the flow of the conversation. The audio of participants’ performance was recorded in digital format. Participants who used an inappropriate paraphrase that resulted in avoidance of the target verb form were prompted to rephrase their translations.

The dialogues were designed so that the RH and AH appeared an equal number of times in all combinations within the 15 segments. To prevent participants from noticing a pattern and to allow for natural dialogue, the frequency of each category was not equally distributed in each segment. However, care was taken to ensure that the distribution of items from each category was fairly even throughout the 15 segments. Distractors were neither necessary nor plausible, as any fully formed sentence in Korean will typically entail a decision to supply RH marking and the need to choose the appropriate AH form.

It was emphasized, at the beginning of the experiment, that each participant’s utterance should sound completely authentic. In other words, a child character should speak like a child, using appropriate words and expressions. These instructions were designed to encourage speakers to use appropriate registers without calling their attention to the actual focus of the study. Upon completion of the task, participants were asked to fill out the language background questionnaire and C-test taken from Lee-Ellis (2009) as a measure of their proficiency. In a short debriefing session, they were asked about the difficulty of the task and what they noticed while engaged in the experimental task. None of the participants reported awareness of the purpose of the study. The duration of the experiment was approximately 90 minutes.

RESULTS

Combinations of the two addressee and two referent honorific categories (the combinations corresponding to those shown in the chi square tables) comprised the four item types. Scores on each item type were treated as the dependent variable.

Native speaker data was collected prior to the experiment to confirm that the situations in the teledrama translation task do, in fact, elicit the target forms consistently. Participants’ translation of each target sentence was marked as correct if it included the appropriate RH and AH marking. No partial credit was given for errors. An example of a translation segment with required honorific marking for each turn can be found in Appendix A. Each segment involved multiple items of the four item types. The script segments in combination presented a total of 12 items of each type.

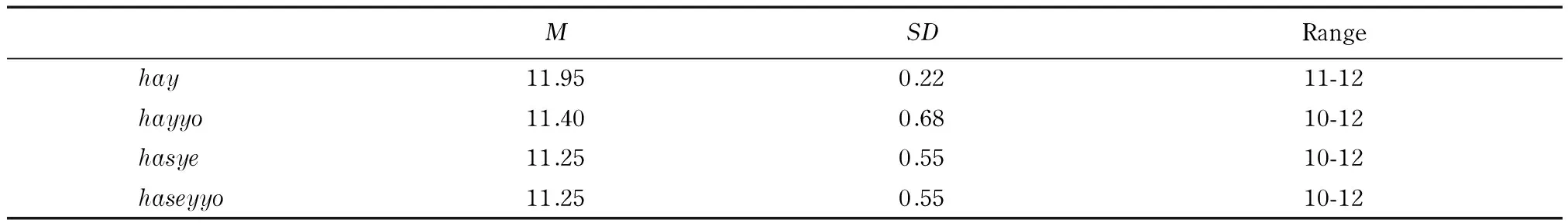

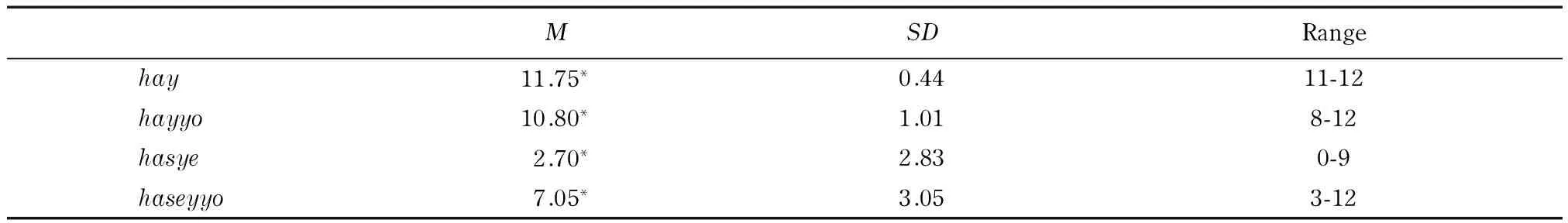

The mean results of the NS group are shown in the Table 7.

Table 7 The Mean Scores and Standard Deviations of the Four Item Types for the NS Group

Note.N=20 in each cell; *p<0.05. Maximum possible score was 12 in each cell.

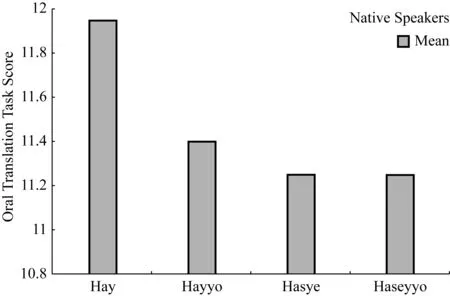

NSs’ performance for the four target RH/AH combinations were close to ceiling, demonstrating that the task successfully elicited the target structures. As can be seen, the combinations involving some form of honorification (i.e., referent, addressee, or both) exhibited slightly lower scores, indicating that even NSs occasionally show slight variation when deciding how to apply honorifics (see Figure 1). However, this variation was minor.

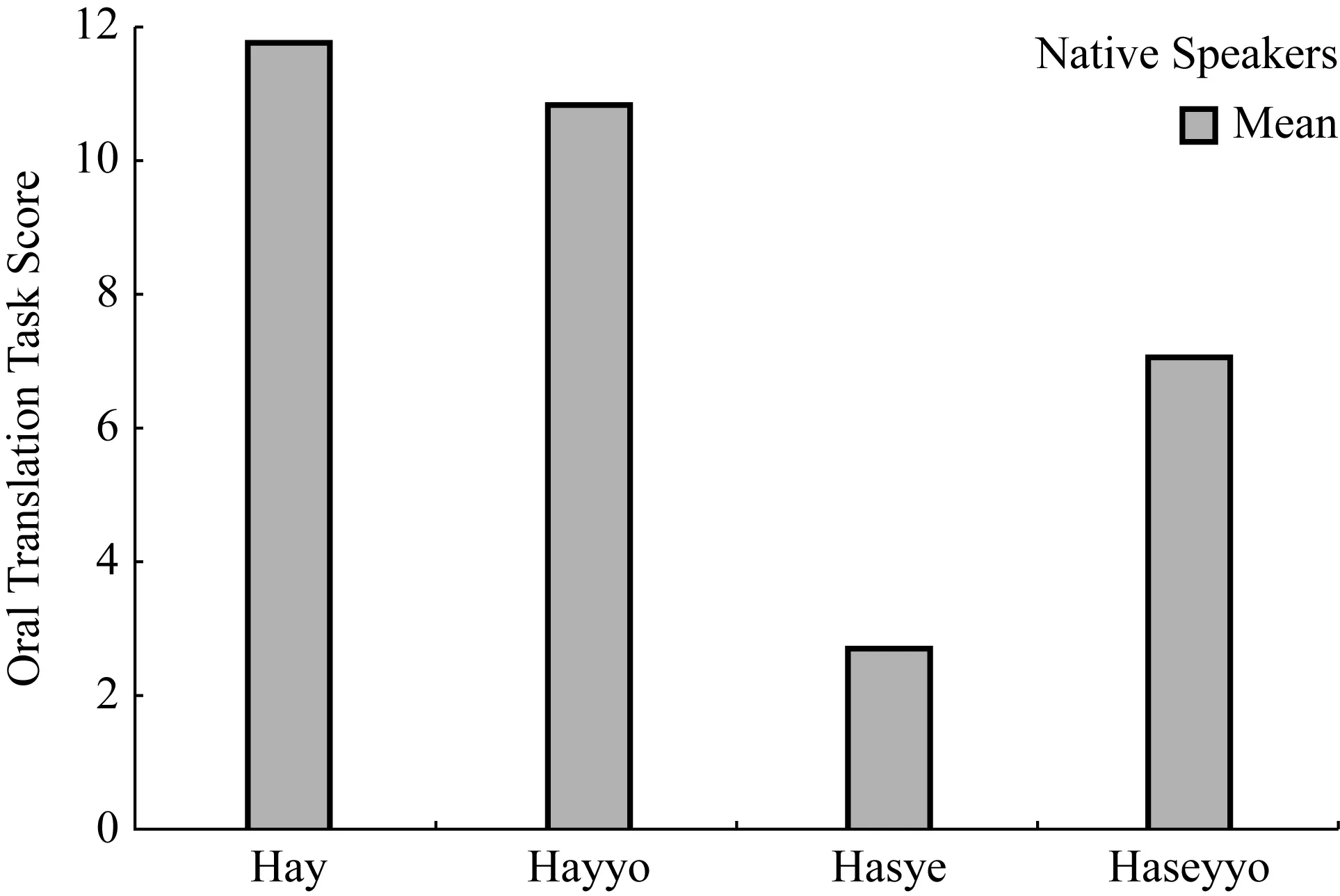

The NNS results are shown in Table 8.

Figure 1 The mean scores of the four item types of NS group

Table8 The Mean Scores and Standard Deviations (SD) of the Four Item Types for the NNS Group

MSDRangehay11.75*0.4411-12hayyo10.80*1.018-12hasye2.70*2.830-9haseyyo7.05*3.053-12

Note.N=20 in each cell; *p<0.05. Maximum possible score was 12 in each cell.

As can be seen, NNSs exhibited markedly greater accuracy on items that did not require RH marking. As predicted by H1, participants were more accurate onhaseyyothan onhasye. In fact, all 20 participants exhibited better accuracy on the former RH/AH combination (see Figure 2).

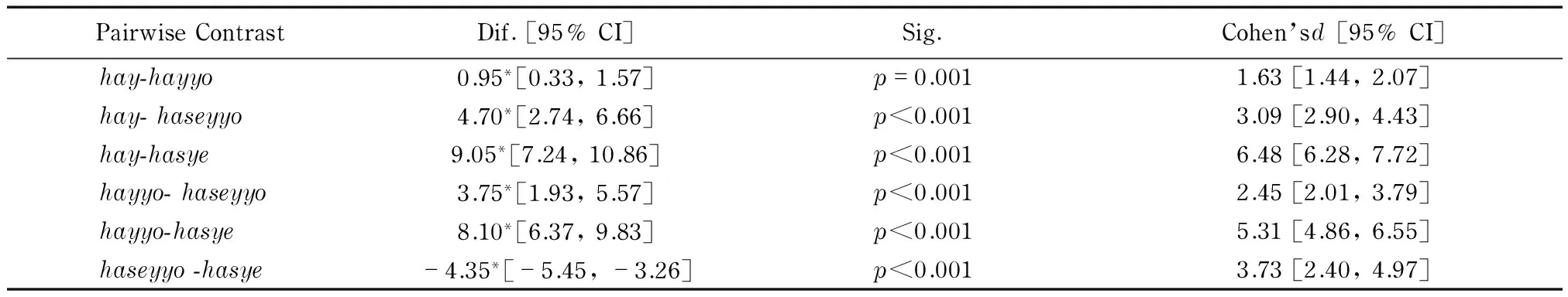

As both H1 and H2 predict, the easiest RH/AH combination ishayfollowed byhayyo. As H1 but not H2 predicts,haseyyowas easier thanhasye. These greater accuracy forhaseyyowas highly reliable, whereas the effect size (d=3.73) was between small and moderate.

Figure 2 The mean scores of the four Item types of NNS group

Table9 Pairwise Comparisons of Mean Differences and Effect Sizes with Confidence Intervals (CI) of Four AH/RH Combinations for the NNS Group

PairwiseContrastDif.[95%CI]Sig.Cohen’sd[95%CI]hay-hayyo0.95*[0.33,1.57]p=0.0011.63[1.44,2.07]hay-haseyyo4.70*[2.74,6.66]p<0.0013.09[2.90,4.43]hay-hasye9.05*[7.24,10.86]p<0.0016.48[6.28,7.72]hayyo-haseyyo3.75*[1.93,5.57]p<0.0012.45[2.01,3.79]hayyo-hasye8.10*[6.37,9.83]p<0.0015.31[4.86,6.55]haseyyo-hasye-4.35*[-5.45,-3.26]p<0.0013.73[2.40,4.97]

Note.N=20 in each cell, *p<0.05, Bonferroni adjustment; CI=confidence interval upper and lower,d=Cohen’sd

DISCUSSION

The experimental results confirmed H1 and disconfirmed H2 and H3, providing important support for the DBH. NNSs were shown to display a significant difference in their performance on the four item types, with performance best on the most frequently occurringcombinations, that is, the (-) RH intimate AH category, followed by the (-) RH polite AH category, which was, in turn, followed by the (+) RH polite AH category. Performance was worst on the (+) RH intimate AH category.

These results are consistent with the view that second language learners may systematically conflate grammatical categories when this conflation is supported by distributional biases in the input and semantic correspondence between the target grammar structures. If learners were oblivious to the distributional bias affecting the RH/AH combinations but were sensitive solely to the observed frequency of the individual RH and AH forms, they would be expected to perform best on combined forms based on the cumulative frequencies of the individual RH and AH forms (i.e., as predicted by H2).

Even if frequency-based explanations are abandoned entirely, it is difficult to reconcile alternative accounts with the findings. If thehayform of AH is easier than thehayyoform of AH to acquire, as the findings clearly suggest, and if the combined frequencies of the RH and AH forms are omitted from an explanatory account, it is not clear why simply adding the RH tohay(i.e.,hasye) and tohayyo(i.e.,haseyyo) should lead to a reversed pattern in NNSs’ performance.

One possible factor that has not been considered thus far is the effect of task difficulty on NNSs’ performance. Several authors (Robinson, 2005; Skehan & Foster, 2001) have suggested that oral tasks involving more elements may make greater cognitive demands, leading to decreased fluency and/or accuracy. Cognitive complexity could explain the current results as the RH/AH combinationhasyetends to occur almost exclusively with third-person referents. This tendency is explained by the nature of the honorifics: RH marking is typically not used with the intimate AH form unless the verbal referent and addressee are different. The other three target combinations (hae,hayyo, andhaseyyo), on the other hand, tend to occur with both second and third person. To test whether this factor influenced the current results, the 12haseyyoitems were subjected to a post hoc analysis. It was reasoned that sentences with third person referents were inherently more difficult, NNS scores on thehaseyyoitems with third person referents should be lower. As part of the study design, thehaseyyoitems had been split between those with second person referents and those with third person referents. An analysis of these items’ NNS scores showed that the items exhibited only a slight difference between scores for second person items (M=3.70,SD=1.63) and third person items (M=3.35,SD=1.66), and a t-test indicated that this 5.8% difference in scores was nonsignificant (p=0.50) at ap<0.05 level. Because only six items from two categories were analyzed, a Type 2 error cannot be entirely ruled out, but the similar scores for both second and third person referents suggests that cognitive complexity due to the target verb’s referent was not a critical factor in the current study.

When interpreting the overall results, several caveats should be noted. First, the corpora used for in the initial analysis are relatively small. Moreover, the teledrama corpus may not be entirely representative of authentic discourse, and even if it is representative, it may not accurately reflect the type of input available to L2 learners of Korean. It must also be noted that the n-size in this study is relatively small. Learners who differed markedly in their exposure to authentic discourse may show different patterns of acquisition.

This study’s consistent findings add to our understanding of SLA processes by providing a new test of the DBH, a hypothesis that has been associated exclusively with aspect studies using a different area of grammar (i.e., tense and aspect). Subsequent research will need to confirm these results using other methodologies. These findings should pave the way for a number of interesting follow-on studies. For example, it would also be interesting to conduct an experiment that differentiated the DBH account from the prototype account. One possible explanation for the current results is that learners tend to conflate the AH and RH solely due to the semantic similarities in the two types of honorifics. To differentiate a DBH and a prototype account, future studies could focus on the deferential form. The small corpus study in this study suggests that the deferential AH (hapnita), unlike the polite AH (hayyo), exhibits anegativeassociationwith RH marking. If the frequency-based acquisition patterns found in this study have broad application, the distributional bias in favor ofhapnita(the deferential AH without RH marking) as opposed tohasipnita(the deferential AH with RH marking) would predict greater accuracy onhapnita, whereas a pure prototype account would predict greater accuracy onhasipnita.

Viewed broadly, this study’s results tentatively suggest that the agglutinative structure of languages like Korean may actually encourage the processing of semantically similar concatenated affixes as unanalyzed chunks at a stage prior to more native-like acquisition. The results may also suggest the need for pedagogical techniques that show the contrast between similar grammatical categories, in order to facilitate advanced learners’ full acquisition of grammatical features such as RH and AH. It is also hoped that this study’s corpus analysis may provide a useful baseline for researchers who are investigating Korean honorifics.

NOTES

1Haydenotes the intimate form (i.e., non-honorific speech style) of the verb “hata(to do).”

2Hayyoindicates the polite form (i.e., honorific speech style) of the verb “hata(to do).”

3Hapnitasignifies the deferential form (i.e., honorific speech style) of the verb “hata(to do).”

Andersen, R. W. (1990). Models, processes, principles, and strategies: Second language acquisition inside and outside the classroom. In B. VanPatten & J. F. Lee (Eds.),Secondlanguageacquisition/Foreignlanguagelearning(pp. 45-68). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Andersen, R. W. (1993). Four operating principles and input distribution as explanations for underdeveloped and mature morphological systems. In K. Hyltenstam & A. Viborg (Eds.),Progressionandregressioninlanguage:Sociocultural,neuropsychological,andlinguisticperspectives(pp. 309-339). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Ayoun, D., & Salaberry, M. R. (2008). Acquisition of English tense-aspect morphology by advanced French instructed learners.LanguageLearning, 58 (3), 555-595.

Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2000).Tenseandaspectinsecondlanguageacquisition:Form,meaning,anduse. Oxford: Blackwell.

Bardovi-Harlig, K., & Bergström, A. (1996). The acquisition of tense and aspect in second language and foreign language learning: A study of learner narratives in ESL and FFL.CanadianModernLanguageReview, 52(2), 308-330.Brown, L. (2008a). The honorifics system of Korean language learners.SOAS-AKSWorkingPapersinKoreanStudies, 2, 1-14.

Brown, L. (2008b). “Normative” and “strategic” honorifics use in interactions involving speakers of Korean as a second language.ArchivOrientální, 76(2), 269-297.

Byon, A. S. (2005). Apologizing in Korean: Cross-cultural analysis in classroom settings.KoreanStudies, 29, 137-166.Eun, J. O., & Strauss, S. (2004). The primacy of information status in the alternation between the deferential and polite forms in Korean.LanguageSciences, 26(3), 251-272.Johnson, K., & Johnson, H. (1998).Encyclopedicdictionaryofappliedlinguistics. Malden: Blackwell.

Kim-Renaud, Y. -K. (1986).StudiesinKoreanlinguistics. Seoul, South Korea: Hanshin.

Kim-Renaud, Y. -K. (2001). Change in Korean honorifics reflecting social change. In T. E. McAuley (Ed.),LanguagechangeinEastAsia(pp. 27-46). London: Routledge.

Lee-Ellis, S. (2009). The development and validation of a Korean C-Test using Rasch Analysis.LanguageTesting, 26(2), 245-274.

Mueller, J., & Mueller, C. M. (2009). Style shift in Korean teledramas: A case for the careful consideration of speech style in translation.Forum, 7 (2), 215-246.

Pienemann, M. (1998). Developmental dynamics in L1 and L2 acquisition: Processability theory and generative entrenchment.Bilingualism,LanguageandCognition, 1(1), 1-20.Quaglio, P. (2009).Televisiondialogue:Thesitcom“Friends”vs.naturalconversation. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Robison, R. E. (1995a). The aspect hypothesis revisited: A cross-sectional study of tense and aspect marking in interlanguage.AppliedLinguistics, 16(3), 344-370.

Robison, R. E. (1995b). Verb inflections in native speaker speech: Do they mean what we think? In H. Pishwa & K. Maroldt (Eds.),Thedevelopmentofmorphologicalsystematicity:Across-linguisticperspective(pp. 199-224). Tübingen, Germany: Gunter Narr Verlag.Robinson, P. (2005). Cognitive complexity and task sequencing: Studies in a componential framework for second language task design.InternationalReviewofAppliedLinguisticsinLanguageTeaching, 43(1), 1-32.

Shirai, Y., & Kurono, A. (1998). The acquisition of tense-aspect marking in Japanese as a second language.LanguageLearning, 48(2), 245-279.

Skehan, P., & Foster, P. (2001). Cognition and tasks. In P. Robinson (Ed.),Cognitionandsecondlanguageinstruction(pp. 183-205). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sohn, H. -M. (1999).TheKoreanlanguage. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.Strauss, S., & Eun, J. O. (2005). Indexicality and honorific speech level choice in Korean.Linguistics:AnInterdisciplinaryJournaloftheLanguageSciences, 43(3), 611-651.

Wode, H. (1983). Phonology in L2 acquisition. In H. Wode (Ed.),Papersonlanguageacquisition,languagelearningandlanguageteaching(pp. 175-187). Heidelberg, Germany: Gross.

APPENDIX A

Example Items of the Dialogue Translation Task

Directions: Based on the following scenario, give a Korean translation of each sentence. Make sure to say each sentence exactly the way the character in the scene would say it. (For example, the translation of a child’s speech should sound like something a child would say, and so on.)

Scenario: Sua and Sua’s grandmother (Mrs. Choi) went shopping at the department store. They ran into Danpoong’s mother and her friend. Danpoong’s mother admires Sua’s grandmother and Sua as they are from rich family.

CharacterEnglishKoreanItemTypes[Thiscolumnwillnotbeshowntoparticipants].Danpoong’smotherHello,Mrs.Choi.Sua’sgrandmotherOh,wemeetagain.Danpoong’smotherYou’reoutshopping!Sua’sgrandmotherThisismygranddaughter.Sua,sayhellotothem.(-)RHintimateAHSuaHello.Sua’sgrandmotherWe’regoingtohavelunch.Willyoujoinusifyouhaven’teaten?(+)RHpoliteAHDanpoong’smotherOh,no.Icamewithafriend.(-)RHpoliteAHSua’sgrandmotherThen,Let’shavelunchsomeothertime.Danpoong’smotherSure.Goodbye.AfterSuaandSua’sgrandmotherleave,Danpoong’smomandherfriendchat.Danpoong’smother’sfriendWhowasthatoldwoman?Sheseemstohavealotofclass.Danpoong’smotherShe’sthemotherofBonjourFoods’sowner.(+)RHintimateAHDanpoong’smother’sfriend(Surprised)Really?

APPENDIX B

Target Sentences Used in the Dialogue Translation Task

CategoryTargetSentenceshaehayyohasyehaseyyo(2ndPerson)haseyyo(3rdPerson)

10.3969/j.issn.1674-8921.2014.12.005

Correspondence should be addressed to Jeansue Mueller, Second Language Acquisition, 3215 Jiménez Hall, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA. Email: muellerj@umd.edu

- 当代外语研究的其它文章

- Acquisition of Mandarin Lexical Tones: The Effect of Global PitchTendency

- Development of Implicit and Explicit Knowledge of GrammaticalStructures in Chinese EFL Learners

- Effects of Explicit Focus on Form on L2 Acquisition of EnglishPassive Construction

- A Meta-analysis of Cross-linguistic Syntactic Priming Effects

- Language Learning Strategies in China: A Call for Teacher-friendlyResearch

- Call For Papers