Rainwater harvesting in the challenge of droughts and climate change in semi-arid Brazil

Johann Gnadlinger

(Regional Institute for Appropriate Small-Scale Agriculture, Juazeiro 48907-200, Brazil)

Rainwater harvesting in the challenge of droughts and climate change in semi-arid Brazil

Johann Gnadlinger

(Regional Institute for Appropriate Small-Scale Agriculture, Juazeiro 48907-200, Brazil)

Some successful experiences of rainwater harvesting in Brazil’s semi-arid region are shown: how rural communities are living during the severe drought from 2011 to 2013, using technologies of rainwater harvesting for the household, in agriculture, livestock raising and the environment. Starting from the positive experiences, principles of living in the challenge of droughts and climate change are elaborated and summarized into different guidelines for sustainable livelihood and production: access to water and sufficient land area; rainwater harvesting to provide water security to households and communities; preservation, recovering and management of drought-resistant vegetation; emphases on raising of small and medium sized livestock and water and forage storage; appropriate crop selection and sustainable extraction, processing and marketing of crop products; capacity building of the people. These principles contribute to preparing a national policy on living in harmony with the semi-arid climate. Rainwater harvesting is an important part of a package of measures which enables a sustainable livelihood in such a difficult environment.

rainwater harvesting; semi-arid climate; resilience; sustainable livelihood; policies

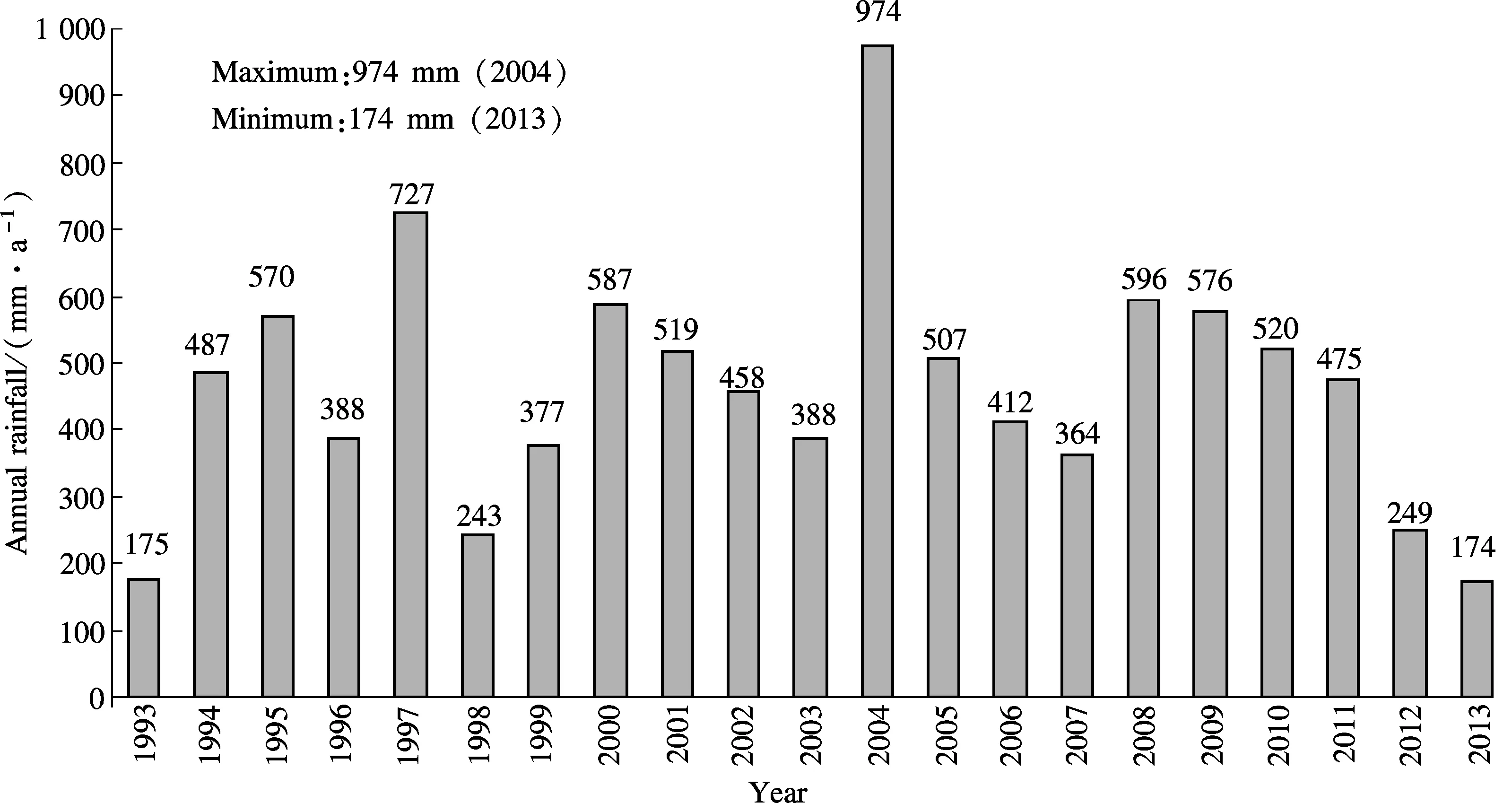

Semi-arid Brazil (SAB) in the Northeast of the country (see Fig.1), extending over 980133 km2and 1135 municipalities, is inhabited by 22 million people, 8.5 million of them in the rural area[1]. It is not little, but irregular rainfall, which characterizes SAB. The city of Juazeiro in the center of SAB has an average yearly rainfall of 510 mm. In a drought year there could be only 174 mm rainfall, whereas in another year one could have 974 mm (see Fig.2). The evaporation rate is high, due to continuous high temperatures (open surface evaporation of about 3000 mm a year).

Fig.1 Map of Brazil, showing semi-arid Brazil in the Northeast of the country (Gnadlinger)

Droughts are part of the semi-arid climate and occur in a cycle of 25 to 30 years. In 2012 and 2013, a severe drought event occurred with only 30% of average rainfall. The last similar drought happened from 1979 to 1983 with devastating consequences for the rural population: a high mortality rate among the elderly and children and an increased migration of young people to cities. Although these effects have not been repeated for the affected people this time, the challenge now is: How do the people, the civil society and the government deal with the actual drought? What is the contribution of rainwater harvesting? What lessons can be learned for living successfully in the semi-arid region notwithstanding droughts and climate change.

1 Approach

1.1 Droughts in semi-arid Brazil

When one or two or three years of low rainfall happen, it is not a catastrophe for nature with its plants and animals. Over a period of thousands of years nature has been able to adapt to droughts and build resilience. A catastrophe is rather the lack of preparation of the people and especially the government. The federal and state governments had a period of three decades since the last severe drought to prepare and not be caught by surprise. But, once again, the governments needed to take emergency measures, spending enormous sums of money to avoid major economic losses and deaths in the population. Since the beginning of 2012, a government emergency drought relief program has been trucking water to rural households and supporting families with money. We watched a parade of water trucks, the resurgence in full force of the so-called drought industry and lament the lost time, in which the SAB could have been endowed with infrastructure and courageous policies. As an example of a lack of preparation: in March 2013, Brazil’s central region exported 20×106t of its super corn harvest to China and the USA, but CONAB, the National Food Supply Company, was unable to send 5×105t of corn to the drought-ridden SAB needed as livestock feed. There was no corn available in the SAB during that period[2].

Fig.2 Annual rainfall variability in SAB (Embrapa/Irpaa)

1.2 Living in harmony with the semi-arid climate

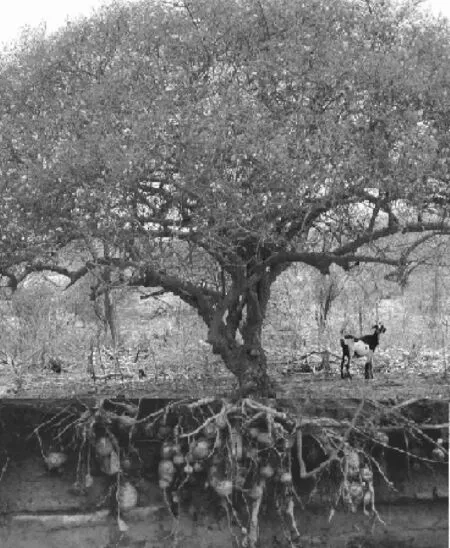

On several occasions, farmers, livestock raisers, community representatives and even policy makers have showed how it is possible to live with the drought[3]. Some of the rural population was already prepared through awareness building in previous years when they studied: What are the real reasons of suffering from drought? Droughts are longer than normal dry periods with less than average rainfall, but the consequences of droughts are man-made: little or no water management, deforestation, climatically inappropriate farming practice, lack of access to land, social and political exploitation. Native plants of the Caatinga vegetation accumulate water and nutrient reserves, having potato-like roots (see Fig.3) and thick trunks to store water or deep roots to fetch it; they avoid unnecessary evaporation; they produce and reproduce less in drier years, but they do not die. The lesson from nature is that human activities must also meet the concept of multiple-year preparation, similar to nature: The water supply needs to be planned, not for eight months, but for two years or more. Forage must not be exhausted within a few months or a year and be produced on location. Bank credit for crop and livestock production needs to be rethought according to multiple years.

Fig.3 Umbu-tree (Spatodia) as an example for storing water in potato-roots (Gnadlinger)

2 Five Steps of Water Supply

The semi-arid region needs to diversify the sources of water according to its end use. In many parts of the SAB where there is crystalline bedrock it is not viable to drill wells since no groundwater exists. But, despite the problems of uneven rainfall distribution, high evaporation and unfavorable subsoil, it is always possible to catch water when it rains, store it and, therefore, have a safe source of water during the dry season, not only for drinking but also for other uses. Thus a new idea is emerging: the integrated management of rainwater, surface water, soil and groundwater, respecting the water cycle[4].

The struggle for access to water must also be accompanied by a concern for a size of land area suitable for semi-arid climate conditions. With infra-structure and good management, it will be possible to have sufficient water for different uses in the local communities under semi-arid conditions and also during drought periods, especially if the following five steps are considered:

1) Drinking water should come preferably from cisterns, constructed near the house, large enough to store rainwater caught during the rainy season for use during the long dry season, giving residents comfortable access to water. In Brazil, access to drinking water is a priority in the case of water scarcity[5]. 750000 cisterns of 16000 L for drinking water have already been constructed by the private sector with funding from the federal government during the past 12 years, 527438 alone by ASA—the semi arid network (see Fig.4)[6]. Furthermore, since 2012, the Ministry of National Integration is distributing PVC cisterns, provided by a multinational company, but criticized because of lack of community involvement.

Fig.4 One of the hundreds of thousands cisterns built in SAB by the organized civil society (ASA)

2) Water for the community, for household use such as bathing, washing dishes and clothes, and livestock consumption, is provided by narrow trench-like ponds, dug into the rock and at least 4 m deep (see Fig.5) and wells. More than 1000 manual water pumps (called Volanta pumps) were installed by ASA especially in low-volume wells in crystalline subsoil, providing water for sheep and goats (see Fig.6).

Fig.5 Four-meter deep trench-like rock cisterns holding back water for goats during the drought of 2012 (Gnadlinger)

Fig.6 Volanta hand pump with a fly wheel takes water out from cracks in the crystalline subsoil (Irpaa)

3) Water for agriculture is supplied through sub-surface dams (see Fig.7), cisterns or ponds for salvation irrigation, road catchments to irrigate fruit trees, contour level plowing, rain water stored in situ for fruit trees or sorghum, use of manure and dry mulch (straw) to retain soil moisture for plants, crops adapted to the climatic conditions. ASA constructed 14343 cisterns of 52000 L for irrigation of vegetables and fruit trees.

Fig.7 Sub-surface dam construction, putting a PVC sheet (Irpaa)

4) Water for emergency situations during a long drought period is provided by deep wells and small dams strategically distributed. This point is an interim solution while the three previous points are not fully achieved.

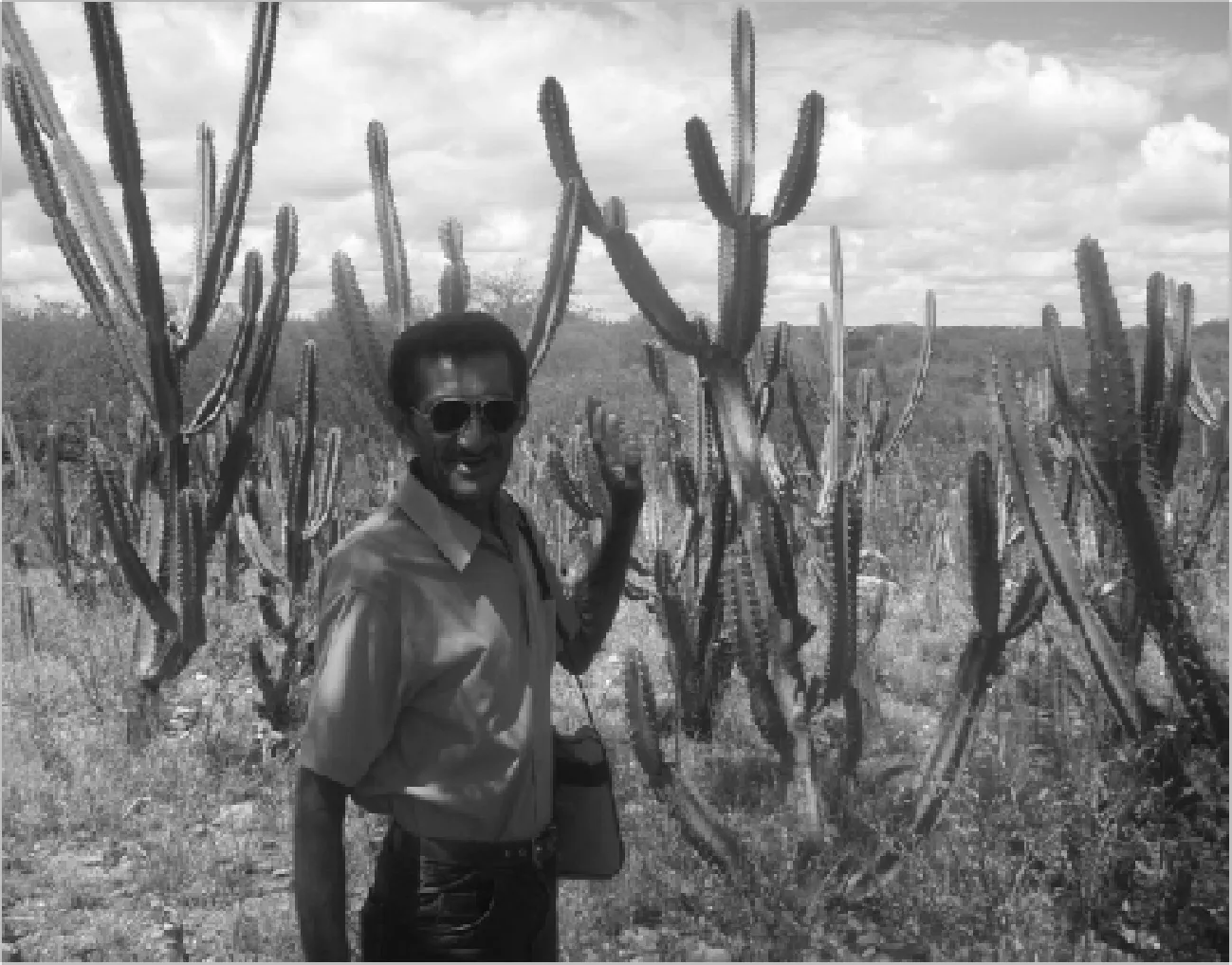

5) Water for the environment is through protection of springs and riparian vegetation, prevention of water source contamination, not burning the Caatinga vegetation nor burning the fields. The knowledge of the water cycle and water balance is the pre-condition for a harmonious living with the climate and the environment. The environment provides water for the needs of humans but part of this should be available for conservation and proper functioning of the ecosystem. A variety of watershed management programs in temporary rivers and of natural vegetation recovery programs, called “re-Caatinga mento”, are underway (see Fig.8). The intact Caatinga and the lumpy soil provide good infiltration of rainwater, preventing erosion.

Fig.8 Re-Caatinga mento: cactus planted in years of high rainfall saves food for animals during the drought (Gnadlinger)

These five water management steps are the result of concrete discussions with rural communities and make possible the elaboration of decentralized and participative Municipal Water Plans in the municipalities of the SAB, prepared and implemented by the public and private sectors. At this point the São Francisco River diversion must be mentioned, a project that aims to benefit large companies and enterprises, supplying mostly coastal cities, having nothing to do with quenching the thirst of the semi-arid Northeast as informed by official propaganda.

3 Towards a Policy of Sustainable Livelihood inSAB

Rainwater harvesting alone is not capable of solving the problems of droughts and climate change. It must be included in an overall management program. The requirement for a sustainable comprehensive structure in the SAB means to multiply successful experiences all over the SAB. For this reason the principles of Living in Harmony with the semi-arid climate can be summarized in the following guidelines[7]:

1) Guarantee access to water and sufficient land area to raise livestock and produce in the semi-arid conditions. The SAB Agro-ecological Land Zoning[8], conducted by Embrapa Semiarido, the Brazilian Agricultural Research Agency, shows the correct use of the land, according to climate and soil, but also indicates the minimum property area. This data should be the basis for land titling, land reform projects, bank loans, etc.

2) Prioritize decentralized water supply systems and local rainwater harvesting solutions to provide water security.

3) Prevent desertification: avoid large livestock unfit for the SAB such as cattle, deforestation of large areas and production of crops that are not adapted to the semi-arid climate.

4) Preserve, recover and manage the native Caatinga vegetation which resists drought and probably climate change (see Fig.6). The Caatinga is the natural heritage of the SAB and a guarantee for a sustainable life of the people.

5) Prioritize the raising of small and medium-sized livestock (goats and sheep), because the SAB is an excellent region for livestock.

6) Store fodder for the months without rain and even longer than a year, preserving the richness of the Caatinga vegetation through its rational use for breeding and harvesting.

7) Select crops that are able to get along with the irregular rainfall in those parts of the SAB with microclimates, where crop production can be indicated. State agencies should also support marketing in order to guarantee the farmers’ success.

8) Harvest, process and market products of native fruits such as umbu (Spatodia), passion fruit and others, which have a good economic potential and contribute to the preservation of the biome. The inclusion of these products in the local school food programs must be a government priority.

9) Focus efforts on skills and capacity building in rainfed agriculture of the SAB agricultural universities and technical schools because of the great potential of the Caatinga. Irrigated areas are of little expressiveness, and only about 4% of the SAB are economically suitable for irrigation.

10) Discuss these points with communities and their social organizations, in different forums, networks and coalitions to propose and construct a National Policy on Living in Harmony with Climate in the Semi-arid Region at the municipal, state, regional and federal levels.

4 Outlook

At the end of 2013 the rain returned in many parts of the region bringing some relief to the almost three years’ drought, but the opportunities to rethink and plan the SAB after a big drought should not be lost[9],especially in the context of climate change, when more severe drought events are predicted for the SAB region[10].

•A “Survey of the situation of rural small-scale family farming communities” is underway, especially on the situation of water for humans and fodder for livestock (goats and sheep).

•This survey also includes a “list of positive experiences”, how some farmers and rural communities are able to live successfully with the actual drought situation.

•In March 2013, the SAB private sector published in Recife “Guidelines for living with semi-arid conditions” as its contribution to build public policies on this topic.

•At the same time, the Pernambuco state government promulgated the living in harmony with semi-arid conditions law[11].

•Different municipalities are elaborating a “Water program for the rural area”; Bahian municipalities discussed about a municipal policy of living in harmony with semi-arid conditions.

•In October 2013, the EMBRAPA Semiarido and IRPAA organized the semi-arid show about “How to live with drought conditions” in Petrolina, Pernambuco state.

All these initiatives should contribute to bringing the discussion about the “National Policy on Living with the semi-arid conditions” to the National Congress.

Looking further afield, in the past, the SAB has received useful ideas from abroad for its development programs, for example from the rainwater harvesting program of the semi-arid region in Gansu Province, in China. Also, there now exists an initiative to exchange experiences between SAB and semi-arid regions in sub-Saharan Africa.

To conclude, we recall the visionary words of Father Cicero Romão Batista, famous in the semi-arid region, who said 80 years ago on the occasion of the 1932 drought: “The people of the Brazilian Northeast should be prepared to endure three years of drought one after the other!”

[1]National Institute of the Semiarid Region (INSA). Synopsis of the demographic census for semiarid Brazil [EB/OL]. (2005) [2014-05-12]. www.insa.gov.br/censosab/publicacao/sinopse.pdf.

[2]Globo Rural. Forte seca prejudica safra de milho no Nordeste (Severe drought affects corn harvest in Northeast Brazil) [EB/OL]. (2013)[2013-03-10]. http://globotv.globo.com/rede-globo/globo-rural/t/edicoes/v/forte-seca-prejudica-safra-de-milho-no-nordeste/2450281/.

[3]Gnadlinger J. Rainwater catchment and management in the rural area of semi-arid Brazil for climate adaptation—current practice, policy and institutional aspects [J].InternationalJournalofRainwaterCatchmentSystems, 2011,1: 3-15.

[4]Gnadlinger J. Community water action in semi-arid Brazil: an outline of the factors for success [C/OL]//OfficialDelegatePublicationofthe4thWorldWaterForum. Mexico City, 2006: 150-158. http://webmirror.flamble.co.uk/downloads/wwf3.pdf.

[5]Brazil. Brazilian water right,law No.9433, Art.1, Ⅲ[EB/OL].(1997-01-08) [2014-05-12]. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil-03/Leis/L9433.htm.

[6]ASA. Knowledge that comes from the land [EB/OL].(2013) [2014-05-12]. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PVXFUJePGxc.

[8]IRPAA. Seca no Semiárido? (Drought in semi-arid Brazil?) [EB/OL]. [2014-05-12]. http://www.irpaa.org/publicacoes/artigos/seca-no-semiarido.pdf.

[7]EMBRAPA. Agro-ecological zoning of the Brazilian semi-arid region, Brasilia, 2000 [EB/OL].(2000) [2014-05-12]. http://www.uep.cnps.embrapa.br/zoneamentos-zane.php.

[9]Fishman C. Don’t waste the drought [N]. The New York Times. (2012-08-16) [2014-05-12]. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/17/opinion/dont-waste-this-drought.html?-r=0.

[10]Nobre C A, Oyama M D, Sampaio G O, et al. Impact of climate change scenarios for 2100 on the biomes of South America [EB/OL]. (2004)[2014-05-12]. International Clivar Science Conference. Baltimore, MD, USA. http://mtc-m15.sid.inpe.br/rep-/cptec.inpe.br/walmeida/2004/12.22.11.08.

[11]Pernambuco State. Lei Ordinária No.1295/2013 Política Estadual de Convivência com o Semiárido (law of state policy of living with the semi-arid climate) [EB/OL] (2013)[2014-05-12]. http://www.alepe.pe.gov.br/paginas/verprojeto.php?paginapai=3597&numero=1295/2013&docid=FB411BB31071C21C03257B1A0054E3EF.

巴西半干旱地区干旱和气候多变情况下的雨水收集

Johann Gnadlinger

(Regional Institute for Appropriate Small-Scale Agriculture, Juazeiro 48907-200, Brazil)

通过巴西半干旱地区的一些成功案例,介绍了当地农村社区在2011~2013年严重旱灾期间所采取的有效措施:对生活用水、农业用水和畜牧用水采取水资源管理技术;对土壤湿度和含水层采取诸如蓄水池、地下水坝等环境保护措施.根据这些经验,总结出旱灾和气候变化环境下的生活原则,并制定成可持续性生活生产的指导方针:获取足够的水资源和土地面积;利用雨水以保证家庭和社区的用水安全;种植、养护与管理抗旱植物;倡导对中小型家畜养殖的水和饲料储存;加强农作物品种甄选及其产品的可持续生产、加工和销售;重视居民的水资源保护思想和能力培养.这些原则为指导干旱气候条件下人与环境和谐相处提供了宝贵的经验.

雨水利用;半干旱气候;适应性;可持续生活;政策

TU992

:Johann Gnadlinger.Rainwater harvesting in the challenge of droughts and climate change in semi-arid Brazil[J].Journal of Southeast University (English Edition),2014,30(2):164-168.

10.3969/j.issn.1003-7985.2014.02.005

10.3969/j.issn.1003-7985.2014.02.005

Received 2013-10-30.

Biography:Johann Gnadlinger (1948—), male,environmental and water manager, johanng@terra.com.br.

Journal of Southeast University(English Edition)2014年2期

Journal of Southeast University(English Edition)2014年2期

- Journal of Southeast University(English Edition)的其它文章

- Stormwater management of urban greenway in China

- Development,assessment and implementation of integrated stormwater management plan:a case study in Shanghai

- Household model of rainwater harvesting system in Mexican urban zones

- Testing and analysis of rainwater quality in Shenyang

- Pollution control of outfall of rainwater-sewage confluence in old town

- Prediction on effectiveness of road sweepingfor highway runoff pollution control