学龄前儿童看电视时间和饮食模式的相关性研究

宋沅瑾 董叔梅 姜艳蕊 孙莞绮 王 燕 江 帆

·论著·

学龄前儿童看电视时间和饮食模式的相关性研究

宋沅瑾1,2董叔梅1,2姜艳蕊1,2孙莞绮1,2王 燕1,2江 帆1,2

目的 探讨学龄前儿童看电视时间与饮食模式的相关性。方法 选取上海市虹口区全部11所幼儿园儿童及其家长作为调查对象。①采用“儿童个人及家庭社会环境问卷”调查儿童及其家庭基本情况、看电视情况;②以简明版食物频率问卷(FFQ)调查儿童在过去1周内常见食物的摄入频率;③测量儿童的身高和体重。对FFQ中的10个条目,采用主成分分析方法归纳儿童主要饮食模式。以看电视时间<2 h·d-1和≥2 h·d-1分组,分析看电视时间与饮食模式的相关性。结果 共发放问卷1 827份,回收有效问卷1 670份(91.4%)。进入分析儿童平均年龄(5.1±1.0)岁,其中男童824名(49.3%)。平均BMI(15.8±1.8) kg·m-2,平均BMIZ值为0.015±0.96。①儿童平时看电视时间≥2 h·d-1为12.9%(215/1 670),周末看电视时间≥2 h·d-1为36.6%(612/1 670)。②主成分分析提出2种儿童主要饮食模式,即传统型饮食模式和西方型饮食模式。传统型饮食模式以水果、蔬菜、红肉类、白肉类和主食类等食物为代表,西方型饮食模式主要包括甜食、软饮料和果汁类等。③在调整了年龄、性别、父母受教育程度、家庭收入水平和BMIZ值等因素后,相比看电视时间<2 h·d-1的儿童,平时和周末看电视时间≥2 h·d-1的儿童传统型饮食模式的得分均较低(β分别为 -0.105和-0.102,P均<0.001),西方型饮食模式的得分较高(β分别为 0.138和0.158,P均<0.001)。④多元线性回归分析结果表明,调整了年龄、性别、父母受教育程度和家庭收入水平等因素后,学龄前儿童西方型饮食模式的因子得分越高,其BMI值越高(β= 0.066,P=0.006)。结论 不良的饮食模式可能是导致儿童肥胖的危险因素。学龄前儿童看电视时间会影响其饮食模式,看电视较多的儿童应尤其注意饮食健康。

学龄前儿童; 看电视时间; 饮食模式

近年来,中国的饮食观念和饮食行为发生了较大的变化。有研究表明,自1991至2011年,国内饮食中动物性食物、甜食、油炸食物及植物油的摄入比例明显增高[1]。不健康的饮食行为对健康有较深远的影响,不仅能引发营养问题,导致生长发育受限或肥胖,也能增加癌症、心血管疾病及高血压等慢性疾病发生风险[2~4]。儿童时期尤其是学龄前期是良好行为习惯形成的关键时期,该时期的饮食态度、习惯一旦形成,具有长期稳定性且可能持续终生[5]。因此,此时期对于儿童饮食习惯的保护和干预显得尤为重要。电视作为儿童最常用的娱乐方式之一,可能对儿童的饮食行为产生影响。2009至2010年对美国5~10岁儿童的调查表明,看电视时间较长的儿童摄入蔬菜和水果减少,但对快餐和糖类的摄入增多[6]。而在希腊[7]和西班牙[8]等欧洲国家,看电视时间较长的学龄前儿童总能量摄入更多,高脂和高糖类的食物摄入增多,蔬菜的摄入减少,但在中国等一些饮食结构与西方差异较大的地区,看电视行为是否会对儿童,尤其是饮食习惯形成关键期的学龄前儿童产生影响?研究甚少。

1 方法

1.1 研究设计 本研究对幼儿园的儿童进行个人及家庭社会环境问卷、学龄前儿童食物频率问卷(FFQ)调查,归纳饮食模式,多因素分析儿童看电视时间与饮食模式的相关性。

1.2 伦理 本研究得到上海交通大学医学院附属上海儿童医学中心(我院)伦理委员会审核,并获得家长的知情同意。

1.3 研究对象 选取虹口区全部的11所幼儿园,将其全部儿童及其父母作为调查对象。

1.4 质量控制 成立专业的调查团队(包括流行病学专家,儿童保健医生和实验技术人员等),调查幼儿园均指派1名工作人员作为课题负责人协助调查团队的工作,正式调查前1周组织各幼儿园课题负责人进行培训,统一实施方案细则。调查团队携带测量仪器入园进行体格测量。

1.5 测量方法和工具 2011年4~6月11所幼儿园的调查依次展开。学龄前儿童个人及家庭社会环境问卷和学龄前儿童FFQ均附带书面调查意义说明和填表注意事项,由学生带回家,父母填写完毕后统一收回问卷。

1.5.1 学龄前儿童个人及家庭社会环境问卷 由我院自行编制,主要内容包括儿童性别、年龄、父母亲受教育程度(初中及以上/高中或中专/大专及以上)、家庭年收入(<11万、~17万、>17万)和睡眠时间。问卷中设置专门题项调查儿童平时和周末看电视的时间,划分为4个等级:每天<1 h、~2 h、~3 h和>3 h。

1.5.2 学龄前儿童FFQ 依据现有的FFQ[9],结合本次调查人群特点,形成简明版学龄前儿童FFQ,调查儿童在过去1周内常见食物的摄入频率。简明版FFQ问卷信度分析 ,Kw为0.37~0.85,效度分析,与膳食记录问卷各食物种类相关系数均>0.5[10],在大规模人群中进行调查的可行性较高。该问卷包含10个条目,包括传统主食类、红色肉类、白色肉类、蔬菜、水果、甜食、软饮料、牛奶、水和果汁。10个条目均划分为3个等级:每周0~2次、~5次和>6次。

1.5.3 体格测量 采用标准方法测量儿童的身高和体重[11]。测量时采用统一的测量工具,体重、身高均测量2次取其平均值。测身高时要求被测者脱鞋,直立位;体重测量时要求被检查者着贴身衣物、赤脚。计算BMI =体重(kg)·身高(cm)-2,BMIZ值=(观测值-同年龄性别的平均值)/同年龄性别的标准差[12]。

1.6 看电视时间分组 根据美国儿科学会推荐,2岁以上儿童每天看电视的时间不应超过2 h,将儿童平时和周末看电视时间均分别分为<2 h·d-1和≥2 h·d-1组[13]。

1.7 饮食模式的归纳 对学龄前儿童FFQ中的10个条目,采用主成分分析方法,归纳儿童的主要饮食模式。通过方差最大正交旋转,确保提出因子得分以0为中心,标准差为1的分布。根据主成分分析所得碎石图(scree plot)确定保留主成分数,并在数据库中将因子得分保存为新变量用于分析。食物条目在某一主成分的因子载荷的绝对值≥0.3被认为其在该主成分上有良好的代表性。根据因子得分分布情况,将其分为传统型饮食模式和西方型饮食模式。

1.8 统计学方法 填写了所有条目的问卷为有效问卷。采用Epidata 3.1软件进行数据录入,首次输入完成后,选取20%最为重要的变量(如家庭社会经济状况,看电视时间及食物频率,身高、体重等主要指标),进行二次输入,数据输入错误率为1.62%,符合质控要求(<5%)。

2 结果

2.1 一般情况 发放问卷1 827份,回收有效问卷1 670份(91.4%),男童824名(49.3%)。进入分析儿童平均年龄为(5.1±1.0)岁。平均BMI为(15.8±1.8) kg·m-2,平均BMI Z值为0.015±0.96。平时看电视时间每天≥2 h为12.9%(215/1 670),周末看电视时间每天≥2 h为36.6%(612/1 670)。纳入分析儿童的社会基本情况如表1所示。

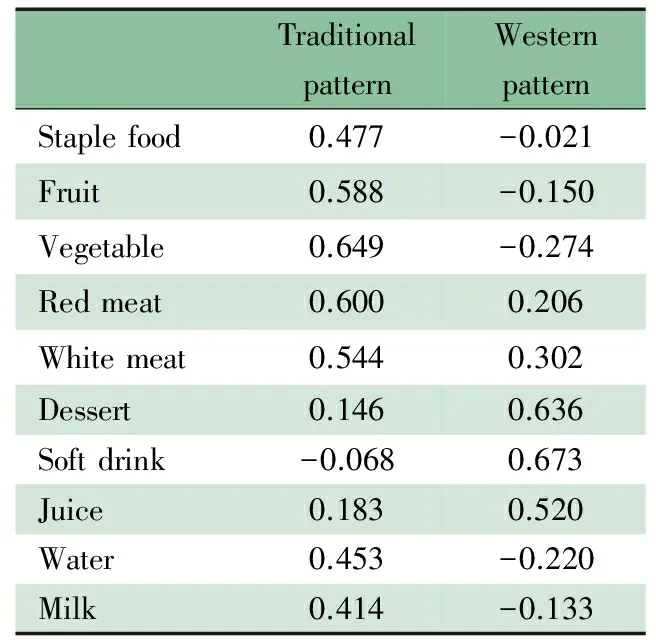

2.2 学龄前儿童饮食模式 主成分分析显示传统型饮食模式和西方型饮食模式的因子累积贡献率为35.13%。10个食物条目在各因子的因子载荷如表2所示。

表2 饮食模式的因子载荷分布

Tab 2 Factor loading matrix for dietary patterns

TraditionalpatternWesternpatternStaplefood0.477-0.021Fruit0.588-0.150Vegetable0.649-0.274Redmeat0.6000.206Whitemeat0.5440.302Dessert0.1460.636Softdrink-0.0680.673Juice0.1830.520Water0.453-0.220Milk0.414-0.133

传统型饮食模式以水果蔬菜、红肉类、白肉类和主食类等食物为代表,西方型饮食模式的代表食物有甜食、软饮料和果汁类等。

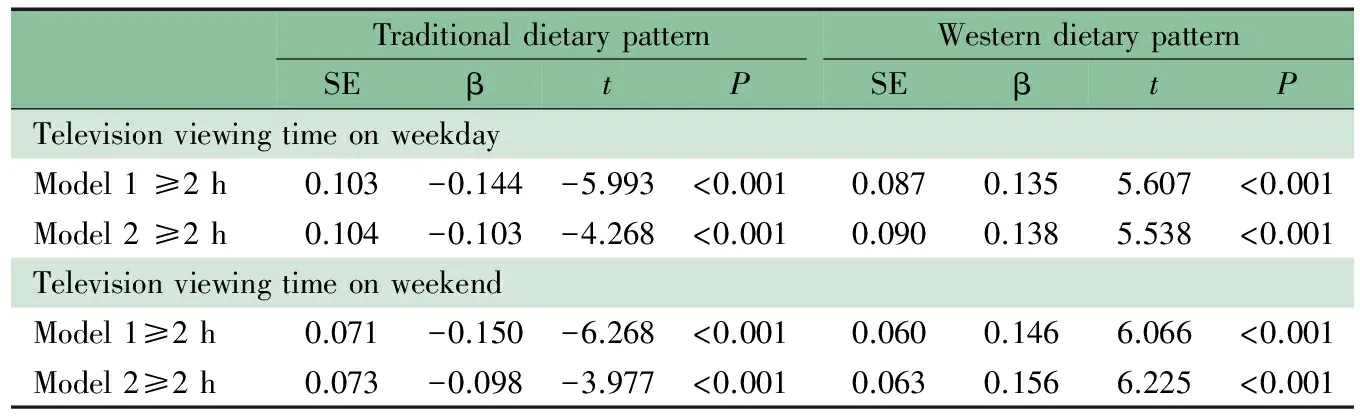

2.3 学龄前儿童看电视时间与饮食模式的相关性分析 在调整了年龄、性别、父母受教育程度、家庭收入水平、BMIZ值等因素后,相较于看电视时间<2 h·d-1的儿童,平时和周末看电视时间≥2 h·d-1儿童的传统型饮食模式的因子得分β分别为 -0.105和 -0.102,P<0.001,西方型饮食模式的因子得分β分别为 0.138和0.158,P<0.001。

2.4 学龄前儿童饮食模式与BMI的相关性分析 在调整了年龄、性别、父母受教育程度、家庭收入水平等因素后,多元线性回归的结果表明,学龄前儿童西方型饮食模式的因子得分与BMI呈正相关(β=0.066,P=0.006);传统型饮食模式因子得分与BMI无相关性(β=-0.017,P=0.483)。

3 讨论

本研究中学龄前儿童平时看电视时间>2 h·d-1为12.9%,周末看电视时间>2 h占36.6%。国内对于学龄前儿童看电视情况的调查数据较少。2000年4~16岁中国城市儿童看电视时间>2 h·d-1占19.5%[14]。2005年调查的中国台湾3岁儿童看电视时间约为1 h·d-1[15],2009年的另1项调查表明,中国台湾3岁儿童看电视时间>2 h·d-1占17.3%[16]。国外数据则显示,澳大利亚2~6岁儿童平时看电视的时间为1.43 h ,周末为1.72 h[8]。

表3 儿童看电视情况与饮食模式得分的多元线性回归分析

Tab 3Multiple linear regression estimates and statistical significance for the association between the dietary patterns and television viewing time

TraditionaldietarypatternSEβtPWesterndietarypatternSEβtPTelevisionviewingtimeonweekdayModel1≥2h0.103-0.144-5.993<0.0010.0870.1355.607<0.001Model2≥2h0.104-0.103-4.268<0.0010.0900.1385.538<0.001TelevisionviewingtimeonweekendModel1≥2h0.071-0.150-6.268<0.0010.0600.1466.066<0.001Model2≥2h0.073-0.098-3.977<0.0010.0630.1566.225<0.001

Notes Model 1:Unadjusted model;Model 2:Adjusted model,control for children′s age, gender, BMI, patents′ education and household income

希腊2004年对1~5岁儿童的调查表明,平时看电视时间为1.27 h,周末为2.88 h,其中3~5岁儿童>2 h·d-1占32.2%,1~3岁儿童占11.0%[7]。日本2~6岁学龄前儿童看电视时间>2 h·d-1者占26.9%[17],美国4~8岁儿童看电视时间>2 h·d-1占30.8%[17]。提示儿童接触电子媒体已经是非常普遍的现象,以上不同的调查数据结果也可能受到研究时间、家庭经济状况、父母受教育程度和父母看电视时间[19]等多种因素影响而有所不同。有必要在同一地区对儿童的看电视行为进行追踪研究,以进一步揭示社会经济变化对其影响的规律。

3.1 儿童饮食模式 儿童饮食中食物种类或营养素摄入形式丰富,且相互影响,往往较难评价。利用食物频率表和主成分分析法评价饮食模式,克服了传统方法的局限性,衡量了人群整体的饮食行为特征和饮食质量,以便在大样本人群流行病学调查中开展,是目前研究整体饮食较常用手段之一[20]。Newby等对自1980年发表的有关饮食模式的文献综述后发现,派生的饮食模式数量为2~25个,因子的累积贡献率为15%~93%[20~22]。但因为各地饮食习惯不同,FFQ的涉及食物条目存在差异,所获得饮食模式的种类和主要饮食命名都存在一定差异。本次研究提取学龄前儿童主要饮食模式,分为传统型及西方型,是饮食模式调查中较常使用的2种。其中传统型饮食模式以蔬菜、水果、肉类和主食等为主,与高加索人种中提出的传统型饮食模式略有差异。高加索人群中较为推荐的传统饮食模式为地中海饮食,以高摄入蔬菜、水果、豆类、坚果、谷物类和橄榄油,适量摄入鱼类以及较少食用奶制品、肉类和家禽肉类等为特征[23]。本研究中以甜食、软饮料和果汁等为代表食物的西方型饮食,与国外研究中讨论的西式饮食模式有一定的相似之处[24],从一定程度上反映西式饮食文化对中国儿童饮食行为的影响。

本研究表明,平时和周末儿童看电视的时间越长,其传统型饮食模式的得分越低,而西方型饮食模式的得分越高,与国外的研究结果基本一致。Manios等[7]研究显示,与看电视时间<2 h·d-1学龄前儿童相比,看电视时间≥2 h·d-1的儿童其每天总能量摄入增加194.6 kJ,而脂肪、肉类和碳水化合物的摄入比例分别增加31%、51%和31%。每天看电视时间≥2 h西班牙儿童摄入更多的甜食,烘焙食品及软饮料[25]。2005年对韩国13~18岁青少年的研究结果显示,看电视时间与健康型饮食模式得分呈负相关,而与西方快餐型饮食模式呈正相关,该研究将健康型饮食模式得分分为低、中和高组,高得分组儿童饮食习惯较好,其接触电子屏幕时间>2 h儿童所占的比例较低得分组低44%[26]。而来自美国的一项干预性研究,4~7岁儿童在减少了看电视时间后,其比对照组总能量的摄入减少,BMIZ值增加,肥胖发生风险减少[27]。

看电视影响儿童的饮食模式,可以解释为:①儿童看电视时常伴随有进食行为,选择高脂高能量膳食的比例较高,零食的摄人也比较多[28]。②电视广告和儿童饮食节目也不同程度的影响儿童饮食观念和饮食行为。广告中关于高脂高糖及高盐类食物较多,而对水果和蔬菜的广告较少[29]。电视广告能不同程度的改变人们对食物营养价值的认识,更多的满足人们心理和情感上的要求而非生理需求[30],改变人们对食物的选择。同时,儿童也更易要求家长购买广告产品[31]。

本研究的局限性:①研究人群局限于上海虹口区,在这一人群中发现的规律推广到更大人群中还需要谨慎,但是作为前期探索性研究,本研究得出的结论可以为今后进一步在更大人群中验证提供前提依据;②本研究采用的是依据学龄前儿童FFQ改编的简明版FFQ,并不能对儿童实际能量摄入及具体食物进行精确判断。③横断面研究只能阐明看电视时间与饮食模式之间有关,但是无法证明其因果关系。

[1]Zhai FY, Du SF, Wang ZH,et al. Dynamics of the Chinese diet and the role of urbanicity, 1991-2011. Obes Rev, 2014,15(S1):16-26

[2]Stephens SK, Cobiac LJ, Veerman JL. Improving diet and physical activity to reduce population prevalence of overweight and obesity: an overview of current evidence. Prev Med, 2014,62:167-178

[3]Huffman KM, Sun JL, Thomas L,et al. Impact of baseline physical activity and diet behavior on metabolic syndrome in a pharmaceutical trial: results from NAVIGATOR. Metabolism, 2014,63(4):554-561

[4]Forman JP, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Diet and lifestyle risk factors associated with incident hypertension in women.JAMA, 2009 ,302(4):401-411

[5]Alles-White M ,Welch P.

Factors affecting the formation of food preferences in preschool children.Early Child Dev Care, 1985, 21: 265-276

[6]Lipsky LM, Iannotti RJ.Associations of television viewing with eating behaviors in the 2009 Health Behavior in School-aged Children Study.See comment in PubMed Commons below Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 2012, 166(5):465-472

[7]Manios Y, Kondaki K, Kourlaba G,et al. Television viewing and food habits in toddlers and preschoolers in Greece: the GENESIS study .Eur J Pediatr, 2009 ,168(7):801-808

[8]Cox R, Skouteris H, Rutherford L,et al.Television viewing, television content, food intake, physical activity and body mass index: a cross-sectional study of preschool children aged 2-6 years. Health Promot J Austr, 2012, 23(1):58-62

[9]Vereecken C, Covents M, Maes L. Comparison of a food frequency questionnaire with an online dietary assessment tool for assessing preschool children′s dietary intake. J Hum Nutr Diet, 2010,23(5):502-510

[10]Flood VM, Wen LM, Hardy LL, et al. Reliability and validity of a short FFQ for assessing the dietary habits of 2-5-year-old children, Sydney, Australia. Public Health Nutr, 2014,17(3), 498-509

[11]De Onis M, Onyango AW, Van den Broeck J, et al. Measurement and standardization protocols for anthropometry used in the construction of a new international growth reference. Food Nutr Bull, 2004 , 25(1):27-36

[12]Li H(李辉),Ji CY,Zong XN, et al.Body mass index growth carves for Chinese children and adolescents aged 0 to 18 years. Chin J Pediatr(中华儿科杂志),2009,47(7):493-498

[13]Saelens BE,Sallis JF,Nader PR,et al.Home environmental influences on children′s television watching from early to middle childhood.J Dev Behav Pediatr,2002,23(3):127-132

[14]Ma GS, Li YP, Hu XQ. Effect of television viewing on pediatric obesity. Biomed Environ Sci, 2002,15(4):291-297

[15]Intusoma U, Mo-Suwan L, Chongsuvivatwong V. Duration and practices of television viewing in Thai infants and toddlers. J Med Assoc Thai, 2013 ,96(6):650-653

[16] Intusoma U, Mo-Suwan L, Ruangdaraganon N.Effect of television viewing on social-emotional competence of young Thai children. Infant Behav Dev, 2013 ,36(4):679-685

[17]Sasaki A, Yorifuji T, Iwase T, et al. Is there any association between TV viewing and obesity in preschool children in Japan? Acta Med Okayama, 2010, 64(2): 137-142

[18]Mendoza JA, Zimmerman FJ, Christakis DA.Television viewing, computer use, obesity, and adiposity in US preschool children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act,2007, 4:44

[19]Economos CD, Must A.Active play and screen time in US children aged 4 to 11 years in relation to sociodemographic and weight status characteristics: a nationally representative cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health, 2008,8:366

[20]Newby P, Tucker KL. Empirically derived eating patterns using factor or cluster analysis: a review. Nutr Rev,2004, 62(5):177-203

[21]Maskarinec G, Novotny R, Tasaki K. Dietary patterns are associated with body mass index in multiethnic women. J Nutr,2000, 130(12):3068-3072

[22]Tseng M, De Vellis RF, Maurer KR, et al. Food intake patterns and gallbladder disease in Mexican Americans. Public Health Nutr,2000, 3(2):233-243

[23]Martnez E, Llull R, del Mar Bibiloni M, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern among Balearic Islands adolescents. Br J Nutr, 2010 ,103(11):1657-1664

[24]Ambrosini GL, Oddy WH, Robinson M, et al. Adolescent dietary patterns are associated with lifestyle and family psycho-social factors. Public ,2009 ,12(10):1807-1815

[25]Bibiloni Mdel M, Martinez E, Llull R, et al. Western and Mediterranean dietary patterns among Balearic Islands′ adolescents: socio-economic and lifestyle determinants. Public Health Nutr, 2012,15(4):683-692

[26]Lee JY, Jun N, Baik I.Associations between dietary patterns and screen time among Korean adolescents.Nutr Res Pract, 2013,7(4):330-335

[27]Epstein LH, Roemmich JN, Robinson JL. A randomized trial of the effects of reducing television viewing and computer use on body mass index in young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 2008 ,162(3):239-245

[28]Van Den Bulck J, Van Mierlo J. Energy intake associated with television viewing in adolescents, a cross sectional study. Appetite, 2004, 43(2): 181-184

[29]Astings G, Stead M, McDermott L,et al. Review of Research on the Effects of Food Promotion to Children [online], 2003. London: Food Standards Agency. Available at http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/foodpromotiontochildren1.pdf. Accessed 16 December 2004

[30]Ynton-Jarrett R, Thomas TN, Peterson KE, et al. Impact of television viewing patterns on fruit and vegetable consumption among adolescents.Pediatrics, 2003, 112(6 pt 1): 1321-1326

[31]Coon KA, Tucker KL. Television and children′s consumption patterns. A review of the literature. Minerva Pediatr, 2002,54(5):423-436

(本文编辑:丁俊杰)

Association between television viewing time and dietary patterns among preschool children

SONGYuan-jin1,2,DONGShu-mei1,2,JIANGYan-rui1,2,SUNWan-qi1,2,WANGYan1,2,JIANGFan1,2

( 1DepartmentofDevelopmentalandBehavioralPediatrics,ShanghaiChildren′sMedicalCenteraffiliatedtoShanghaiJiaoTongUniversitySchoolofMedicine,Shanghai200127; 2MOE-ShanghaiKeyLaboratoryofChildren′sEnvironmentalHealth,Shanghai200092,China)

Corresponding Author:JIANG Fan,E-mail:fanjiang@shsmu.edu.cn

ObjectiveTo investigate the association between television viewing time and dietary patterns among preschool children.Methods All the children and their parents from 11 kindergartens in Hongkou District, Shanghai China were included. The Socio-demographic questionnaire was used to collect the basic information and television viewing time of the children. Dietary information was collected by using a simplified food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), which included children′s common food intake during the past week. Principal component analysis was used to derive two dietary patterns based on the FFQ. Children′s weight and height were also measured uniformly and BMI was calculated. Children′s television viewing time was divided into 2 groups using 2 hours as the cutoff point and to explore the association between television viewing time and dietary patterns.ResultsThe final sample consisted of 1 670 children,boys accounted for 49.3%. And average BMI was (15.8±1.8) kg·m-2and BMIZscore was 0.015±0.96. ①On weekdays children who watched TV more than 2 h·d-1were 12.9%,while at weekends were 36.6%. ②Two dietary patterns were labeled as "the traditional dietary pattern" and "the western dietary pattern". The former included fruits, vegetables, red meat,white meat and staple food,whereas the latter included snack, juice, soft drinks and white meat. ③Comparing with children watching TV less than 2 h·d-1, children spending more than 2 h·d-1watching TV seemed to have lower traditional dietary pattern scores but higher western dietary pattern scores, even after adjustment for age, gender, BMI levels, and family income. ④Preschool children with higher western dietary pattern scores appeared to have higher BMI(β= 0.066,P=0.006).ConclusionWestern dietary patterns might be the risk factors for preschooler′ obesity. Shorter television viewing time may be beneficial for pre-school children′s dietary patterns. Children who have excessive television viewing time may need to be encouraged to consume a more healthy diet

Pre-school children; Television viewing; Dietary pattern

国家自然科学基金:81422040,81172685;教育部新世纪优秀人才:NCET-13-0362;科技部973培育项目:2010CB535000;卫生部行业科研专项:201002006;上海市科委项目及启明星追踪:12411950405,13QH1401800;上海市教委曙光计划:11SG19;上海市公共卫生重点学科的资助

1 上海交通大学医学院附属上海儿童医学中心发育行为儿科,转化医学研究所发育行为研究室 上海,200127;2 教育部和上海市环境与儿童健康重点实验室 上海,200092

江帆,E-mail:fanjiang@shsmu.edu.cn

10.3969/j.issn.1673-5501.2014.06.009

2014-10-15

2014-12-03)