太湖浮游纤毛虫群落结构及其与环境因子的关系

李 静, 戴 曦, 孙 颖, 舒婷婷, 刘正文, 陈非洲,*, 卢文轩

(1. 中国科学院南京地理与湖泊研究所湖泊与环境国家重点实验室, 南京 210008; 2. 安徽省农业科学院水产研究所, 合肥 230031)

太湖浮游纤毛虫群落结构及其与环境因子的关系

李 静1,2, 戴 曦1, 孙 颖1, 舒婷婷1, 刘正文1, 陈非洲1,*, 卢文轩2

(1. 中国科学院南京地理与湖泊研究所湖泊与环境国家重点实验室, 南京 210008; 2. 安徽省农业科学院水产研究所, 合肥 230031)

用定量蛋白银染色法,对太湖浮游纤毛虫进行定性和定量研究,同时用多元统计方法分析生物和非生物因子对其影响。在全湖设置32个点位进行季度采样,共检出117种纤毛虫,隶属于3纲、15目、78属,其中95种鉴定到种的水平。纤毛虫平均丰度27 170 个/L(1 500 — 139 150 个/L),平均生物量600.6 μg/L(16.7 — 8736.0 μg/L),以寡毛目、前口目、盾纤目、缘毛目和钩刺目为主。优势种包括:浮游藤壶虫、趣尾毛虫、顶口睥睨虫、银灰膜袋虫、水生钟虫复合种、钟形钟虫、杯铃壳虫、双叉弹跳虫、大弹跳虫、短列裂隙虫、小裂隙虫、圆筒状似铃壳虫。纤毛虫群落结构空间异质性较高,丰度上呈现从南向北、从敞水区向沿岸河口区逐渐增加的趋势;北部湖区以小个体的寡毛目、盾纤目、前口目为主,而南部主要以大个体的寡毛目为主;从功能摄食类群上看,北部各点以食菌种类为主,而南部以食藻种类居多。该类群季节变化明显,于夏季出现丰度峰值,生物量是冬、夏季显著高于春、秋季。通过CCA多元分析发现,太湖纤毛虫群落结构差异主要与水体营养水平、桡足类数量和pH值等有关,且在不同季节由不同的环境因子调控。

定量蛋白银法;太湖;浮游纤毛虫;生物多样性;时空分布;多元分析

因纤毛虫个体较小而形状多样、操作不易、细胞易破裂等原因,对其生态学研究一直较为欠缺。太湖作为大型富营养化浅水湖泊,生境复杂[5]。鉴于以往对太湖浮游纤毛虫的生态学研究不多[6- 7],对太湖浮游纤毛虫的种类组成及其时空分布知之甚少,本研究首次利用定量蛋白银法,对太湖水体中浮游纤毛虫的生物多样性、群落空间分布格局、季节性演替规律及其影响因子进行了研究。

1 材料和方法

1.1 点位布置和样品采集

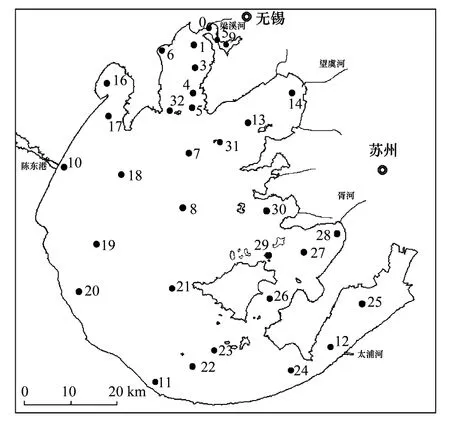

在太湖共设置32个采样点(图1),这采样点分布在太湖断面(三纵三横)和主要入湖河口。分别于2009年2月、5月、8月和11月进行取样,代表太湖冬、春、夏、秋四个季节的情况。采样时,用2.5升采水器采集表层(水下50 cm)、中层和底层(底泥界面以上50 cm)的混合水。水体透明度用Secchi盘现场测定,pH值等指标用YSI 6600水质分析仪现场测定。纤毛虫样品是将1 L混合水倒入白色塑料瓶,用波恩氏液固定(终浓度5%),静置48 h,吸去上清液,浓缩至50 mL备用。浮游甲壳动物样品是取混合水7.5 L,用63 μm网过滤浓缩,用福尔马林保存(终浓度4%);轮虫样品是取混合水1 L,经鲁哥试剂固定(终浓度1%)沉淀后,吸除上清液,浓缩至50 mL保存。将剩余混合水样装入干净的塑料容器中,放入保温箱,并尽快带回实验室以测定分析其他水化学指标。

图1 太湖32个采样点位置Fig.1 Location of 32 sampling sites in Lake Taihu

1.2 样品分析

非生物因子 总磷(TP)、总氮(TN)、硝态氮(NO3-N)、亚硝态氮(NO2-N)、氨态氮(NH4-N)、叶绿素a浓度(Chl a)、总溶解碳(TDC)和总悬浮质(TSS)测定方法参照金相灿和屠清瑛[8]。

生物因子 纤毛虫样品用定量蛋白银法[9]处理:从均匀混合的50 mL浓缩样品中吸取0.5—2 mL不等水样过滤,经琼脂包埋、蛋白银染色、异丙醇和二甲苯梯度脱水、树胶封片、风干等步骤完成制片。将标本置于显微镜(Olympus BX51,日本)下观察,结合活体观察结果进行纤毛虫的鉴定分析。其鉴定和食性区分主要参照Foissner等[10]、Lynn[11]及其它相关文献。生物量的计算主要参照Foissner等[10],个别没有生物量数据的种类则单独计算:挑出一般不少于10只个体,测量虫体长度、宽度和厚度,按照近似几何体体积计算公式计算体积,假定虫体比重为1[12],从而得出该种类单位个体平均生物量值。轮虫和浮游甲壳动物的鉴定参考王家楫[13],蒋燮志和堵南山[14]以及沈嘉瑞等[15],生物量计算参照Dumont[16]与章宗涉和黄祥飞[12]。除纤毛虫以外的生物和非生物因子数据由中国科学院太湖湖泊生态系统研究站提供。

1.3 数据分析

用ArcGIS 9.2软件模拟纤毛虫的空间分布。纤毛虫丰度和生物量差异用独立样本t-检验以及one-way ANOVA来分析。利用CANOCO 4.5软件进行CCA分析,分析前将环境因子数据进行log10(X+1)转化,使其无量纲化且提高分布的正态性。纤毛虫数据矩阵由挑出的优势种组成[17],分析前进行平方根转换,

近年来,伊犁州食品药品监督管理局坚持“四个最严”,落实“四有两责”,深入推进监管体制改革,不断完善监管制度机制,有效加强监管能力建设,各项工作取得了新成效。2015年荣获自治区成立60周年庆祝活动食品药品安全保障工作先进集体。

2 结果

2.1 太湖环境因子

太湖环境因子时空差异明显(表1)。总氮、总磷、总溶解碳和叶绿素a含量季节差异显著(P<0.05)。从空间来看,以总氮、总磷和叶绿素a浓度代表营养水平,北部高于南部,近河口区的采样点一般高于敞水区。总氮和总磷均以28号点最低(总氮1.2 mg/L,总磷0.03 mg/L),而接近河口的16号点(总氮5.8 mg/L,总磷0.31 mg/L)和10号点(总氮5.8 mg/L,总磷0.26 mg/L)均较高。总溶解碳和叶绿素a含量空间差异显著(P<0.05)。后生浮游动物以轮虫数量最多,最高达1 290 个/L,优势种有角突臂尾轮虫Brachionusangularis、萼花臂尾轮虫B.calyciflorus、多肢轮属Polyarthra、螺形龟甲轮虫Keratellacochlearis、矩形龟甲轮虫K.quadrata。轮虫丰度空间差异显著(P<0.01),但是季节差异不明显。枝角类和桡足类主要分布在竺山湾和梅梁湾,其他点丰度显著较低(P<0.001)。枝角类于5月和8月大量出现,5月全湖平均丰度为90.9 个/L,梅梁湾平均丰度达305 个/L,以象鼻溞Bosminasp.和盔形溞Daphniagaleata为优势种;8月全湖枝角类平均丰度为34.8 个/L,以象鼻溞、角突网纹溞Ceriodaphniacornuta和秀体溞Diaphanosomasp.最多。桡足类在8月丰度最高,平均丰度为35.8 个/L,4个月份平均丰度21.1 个/L,优势种有中华窄腹剑水蚤Limnoithonasinensis、汤匙华哲水蚤Sinocalanusdorrii、中剑水蚤Mesocyclopspp.等。

2.2 太湖浮游纤毛虫群落结构

共检出117种纤毛虫,隶属于3纲、15目、78属,其中95种鉴定到种的水平,18种到属的水平。15个目分别为:动基片纲的钩刺目、前口目、肾形目、管口目、吸管目、篮管目、侧口目、合膜目、核残迹目;多膜纲的寡毛目、腹毛目、异毛目;寡膜纲的缘毛目、膜口目和盾纤目。其中食菌、主食藻、营混合营养种类分别为39、25和15种,杂食和肉食性的分别有11

表1 太湖采样点四个季节理化因子(表中数值为平均值及其范围)

和10种;其余17种主要以鞭毛虫或其他资源为食(含食性未明者)。纤毛虫平均丰度和生物量分别为:27 170 个/L(1 500 — 139 150 个/L)、600.6 μg/L(16.7 — 8736.0 μg/L)。寡毛目、前口目、盾纤目、缘毛目和钩刺目最多,其平均丰度占总丰度的比例分别为12 451 个/L(45.9%)、9 264 个/L(34.1%)、3209个/L(11.8%)、975 个/L(3.6%)、710 个/L(2.6%)。优势种主要有:浮游藤壶虫Balanionplanctonicum、小射纤虫Actinobolinasmalli、趣尾毛虫Urotrichafarcta、顶口睥睨虫Askenasiaacrostomia、银灰膜袋虫Cyclidiumglaucoma、水生钟虫复合种Vorticellaaquadulciscomplex、钟形钟虫V.campanula、杯铃壳虫Codonellacratera、双叉弹跳虫Halteriabifurcata、大弹跳虫H.grandinella、短列裂隙虫Rimostrombidiumbrachykinetum、小裂隙虫R.humile、透明裂隙虫R.hyalinum、湖泊裂隙虫R.lacustris、绿急游虫Strombidiumviride、小筒壳虫Tintinnidiumpusillum、筒壳虫一种Tintinnidiumsp.、圆筒状似铃壳虫Tintinnopsiscylindrata、似铃壳虫一种Tintinnopsissp.。

纤毛虫群落存在明显的季节演替,且空间异质性较高(图2—图4)。丰度上,2、5、8、11月平均值分别为24 925、18 328、45 837、19 589 个/L, 2月与5、11月的无显著差异,三者均显著低于8月的(P﹤0.05);生物量上,2、5、8、11月平均值分别为972.0、452.9、715.0、262.5 μg/L,其中2月和8月的显著高于5月和11月的(P﹤0.05)。2月,北部以小个体的盾纤目纤毛虫为主,南部以大个体的寡毛目为主。功能摄食类群上北部以食菌种类为主,如银灰膜袋虫,而南部以食藻的居多,如圆筒状似铃壳虫。5月主要种类是寡毛目和前口目,2月北部占优势的盾纤类在本月数量不多。本月以食藻种类为主,营混合营养的种类,如双叉弹跳虫也数量较多。8月以前口目和寡毛目为主,其中浮游藤壶虫占总丰度的20.4%。营混合营养的双叉弹跳虫和绿色游跳虫Pelagohalteriaviridis也大量出现。11月丰度分布大致呈现从北向南逐渐减少的趋势,最大值在北部近河口的6号点,该点生物量也最高。寡毛目纤毛虫是全湖各点主要类群,盾纤目在6、10、16、17号点所占比重较大,而前口目则在以上4点之外的点位大量出现。食菌和食藻种类共同占据了纤毛虫的大部分,营混合营养的纤毛虫比例较5月和8月大大降低,其他食性的所占比例均较小。

2.3 太湖浮游纤毛虫群落结构与环境因子的关系

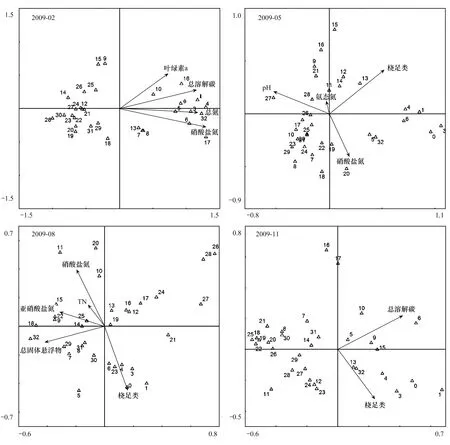

利用向前引入法,最终筛选出4个与2月纤毛虫群落显著相关的环境因子(图5)。第一轴与总氮、总溶解碳、硝酸盐氮、叶绿素a浓度相关性较高,解释的物种变异百分数为27.8%,前两轴共解释了33.1%;第一轴解释的物种-环境关系变异百分数为71.5%,前两轴共解释了85.2%。5月,第一轴与pH值相关性较高,第二轴与氨态氮和硝酸盐氮相关性较高,而桡足类与第一和第二轴均相近。前两轴共解释了物种变异百分数的18.6%,物种-环境关系变异百分数的71.8%。与5月类似,8月的浮游纤毛虫群落结构与桡足类、营养水平和生境异质性(总固体悬浮物)相关性高。前两轴共解释物种变异百分数的23.6%,物种-环境关系变异百分数的65.1%。第一轴与亚硝酸盐氮和总固体悬浮物相关性较高,而第二轴主要由硝酸盐氮和桡足类共同负责。11月的环境因子中,总溶解碳和桡足类显著影响浮游纤毛虫群落组成,但前两轴解释的物种变异数不足15%,表明本月浮游纤毛虫群落结构由多种因子共同决定。

图2 2009年太湖浮游纤毛虫丰度时空分布Fig.2 Spatial and temporal distribution of ciliate abundance in Lake Taihu in 2009

图3 纤毛虫生物量的时空分布Fig.3 Spatial and temporal distribution of ciliate biomass

图4 纤毛虫功能摄食类群时空分布Fig.4 Spatial and temporal distribution of different functional feeding groups of ciliates

图5 太湖浮游纤毛虫群落结构与环境因子的CCA分析图Fig.5 CCA analysis of relationship between ciliate community structure and explanatory environmental factors in Lake Taihu

3 讨论

纤毛虫个体较小而形状多变、一些常见种类个体相似度较高而不易区分,故鉴定时多借助各种染色方法。然而染色后的样品一般无法再进行定性分析。因此,在纤毛虫生态学研究中,往往是定性分析和定量分析分别进行的。但是这样不仅耗时而且得到的数据也易出现偏差。定量蛋白银方法的引入可以同时满足定性和定量分析需求[9]。Pfister等[18]利用该法和一系列传统观察方法,对多种淡水浮游原生动物做了对比分析和研究,发现定量蛋白银法因其对丰度的精确估算和对大多数种类的准确鉴定而有着突出优势。

有研究报道称,用氯化汞、Lugol′s液、福尔马林、戊二醛和Champy-Da Fano分别保存纤毛虫样品3、6、9个月后,其总数量分别减少了7.2%、16.4%、30.7%[19]。由此可见,用传统的保存方法长期保存纤毛虫样品会造成其丰度和生物量的大量损失,不利于后续研究。而用定量蛋白银法,可以及时将纤毛虫样品制成标本,从而能防止细胞破裂,达到长期完整保存样品的目的。但是该法也有其不足之处,比如对累枝虫Epistylis和部分钟虫Vorticella的物种鉴定时,结合显微镜活体观察,往往可取得更快捷有效的结果。虽然目前在淡水湖泊纤毛虫生态学研究中应用该法的报道还不是很多,但因其有上述优点,定量蛋白银法正被越来越多的原生生物学家们所采用。

本次调查中,纤毛虫种类数和丰度与以往太湖的研究结果差异较大[6- 7, 20]。究其原因,除采样范围、采样频次、水体环境较以往不同外,还可能与分析方法有关。在染色制片后,发现了大量的前口类纤毛虫,如浮游藤壶虫和尾毛虫,这些种类在未经染色的情况下,在低倍显微镜观察时易与相似的盾纤类纤毛虫混淆。在这些制片中还发现了大量个体较小(小于20 μm)的种类,如短列裂隙虫和双叉弹跳虫,这些种类在镜检时易被忽略且与属内其他种类易混淆。另外,20世纪80年代以后,太湖水体富营养化加剧,这与纤毛虫丰度的提高可能也有关系[21]。本研究中太湖浮游纤毛虫丰度和生物量与国外一些亚热带富营养湖泊的纤毛虫状况相近[22- 23]。

寡毛目(如急游虫、侠盗虫、弹跳虫),钩刺目(如睥睨虫、栉毛虫)和盾纤目(如膜袋虫)是淡水湖泊浮游纤毛虫群落的典型优势类群[24]。一般随着营养水平增加,3个目纤毛虫数量均有提高,但是优势度有明显变化。寡毛目通常是寡营养湖泊中的绝对优势种,随着湖泊营养水平提高,盾纤目纤毛虫取代寡毛类成为优势种[25]。在太湖北部近河口区,水体营养水平相对较高,该湖区的盾纤目纤毛虫也相对较多。钩刺目纤毛虫优势度与湖泊营养水平无明显关系,可能与水体温度的季节变化有关。另外,在富养化湖泊中,前口目(如尾毛虫,板壳虫,浮游藤壶虫)和缘毛目纤毛虫(如钟虫和累枝虫)也是重要的优势类群[24]。但是本研究中,前口目纤毛虫在营养水平过高的水域中反而数量降低,这可能与其捕食者的数量和盾纤目纤毛虫的资源竞争有关[25]。

在寡营养湖泊中,纤毛虫最大丰度和生物量一般出现在秋季[24];中营养湖泊中,纤毛虫丰度和生物量一般有两个峰值,在温带和亚热带湖泊中这种峰值一般出现在春季和秋季;而在富养化湖泊中,纤毛虫数量和生物量峰值一般出现在夏季[26]。太湖各湖区,浮游纤毛虫数量和生物量峰值一般也是出现在夏季。很多学者认为这种季节动态主要是由其食物资源的变动造成的[27]。太湖夏、秋季由于水华频繁暴发,可食的藻类(主要是隐藻)减少,故而食藻的纤毛虫大量减少;而由于蓝藻碎屑大量存在、细菌数量激增等原因,摄食细菌的、营混合营养方式的以及其他食性的纤毛虫大大增加[28]。

除食物资源等因素的调节作用外,后生浮游动物对纤毛虫群落结构也有很大影响,包括直接的捕食作用、机械干扰作用和间接的竞争作用,而且这些作用因浮游动物和纤毛虫种类不同而不同[2, 29- 31]。本次调查中,桡足类对纤毛虫有明显的抑制作用,而轮虫对纤毛虫则没有明显的作用。在室内培养实验中轮虫可有效捕食大多纤毛虫,但在野外实验和调查中很难发现轮虫对纤毛虫的捕食控制作用[22]。不管在室内培养还是在野外调查中,均发现轮虫和纤毛虫存在营养竞争[32- 33]。McCarthy等[33]在对太湖的调查中发现,因为共用藻类食物资源,纤毛虫和轮虫的总生物量与浮游植物总生物量的比值始终保持相对一致,这与本研究的结果一致。与轮虫不同,桡足类对纤毛虫数量有绝对的控制作用[31]。Archbold 和Berger[34]发现剑水蚤Cyclopsvernalis可以通过捕食有效控制大弹跳虫的数量。Hansen[35]也在该湖发现桡足类对寡毛类纤毛虫有明显抑制作用。在本次调查中未发现太湖枝角类对纤毛虫总数量有明显的控制作用。这可能是因为调查期间枝角类以小型种类为主,如盘肠溞Chydorus和象鼻溞Bosmina,这与前人的工作是相吻合的。例如,Ventelä等[36],Wickham和Gilbert[37]均发现富养化湖泊中,小型枝角类不会抑制纤毛虫生长速率和数量。

致谢: 太湖生态系统监测站提供太湖2009年理化数据。吕志均、钱荣树、蔡永久、姚思鹏、于谨磊、章铭协助采集样品。中国科学院青岛海洋研究所代仁海、孟昭翠、李承春和李玉红在定量蛋白银制片中提供帮助,特此致谢。

[1] Zingel P, Paaver T, Karus K, Agasild H, Nõges T. Ciliates as the crucial food source of larval fish in a shallow eutrophic lake. Limnology and Oceanography, 2012, 57(4): 1049- 1056.

[2] Zöller E, Hoppe H, Sommer U, Jürgens K. Effect of zooplankton-mediated trophic cascades on marine microbial food web components (bacteria, nanoflagellates, ciliates). Limnology and Oceanography, 2009, 54(1): 262- 275.

[3] Zingel P, Agasild H, Nõges T, Kisand V. Ciliates are the dominant grazers on pico- and nanoplankton in a shallow, naturally highly eutrophic lake. Microbial Ecology, 2007, 53(1): 134- 142.

[4] Sommer U, Sommer F, Feuchtmany H, Hansen T. The influence of mesozooplankton on phytoplankton nutrient limitation: a mesocosm study with Northeast Atlantic plankton. Protist, 2004, 155(3): 295- 304.

[5] Chen M, Chen F, Yu Y, Ji J, Kong F. Genetic diversity of eukaryotic microorganisms in Lake Taihu, a large shallow subtropical lake in China. Microbial Ecology, 2008, 56(3): 572- 583.

[6] Xu R L, Nauwerck A. Planktonic ciliates in north region of Taihu Lake, P. R. China. Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Sunyatseni, 1996, 35(Suppl 2): 100- 104.

[7] Cai H. The response of ciliated protozoans to eutrophication in Meiliang Bay of Taihu Lake. Journal of Lake Sciences, 1998, 10(3): 43- 48.

[8] Jin X C, Tu Q Y. Survey Criteria of Lake Eutrophication. 2nd ed. Beijing: China Environmental Science Press, 1990: 10- 302.

[9] Skibbe O. An improved quantitative protargol stain for ciliates and other planktonic protists. Fundamental and Applied Limnology, 1994, 130(3): 339- 347.

[10] Foissner W, Berger H, Schaumburg J. Identification and Ecology of Limnetic Plankton Ciliates. Informationsberichte des Bayer. Landesamtes für Wasserwirtschaft, Heft 3/99, 1999: 1- 793.

[11] Lynn D H. The Ciliated Protozoa: Characterization, Classification, and Guide to the Literature. 3rd ed. New York: Springer, 2008: 1- 605.

[12] Zhang Z S, Huang X F. Method for Study on Freshwater Plankton. Beijing: Science Press, 1991: 1- 414.

[13] Wang J J. Fauna Sinica of Chinese Freshwater Rotifer. Beijing: Science Press, 1961: 1- 288.

[14] Chiang S C, Du N S. Fauna Sinica, Crustacea: Freshwater Cladocera. Beijing: Science Press, 1979: 1- 297.

[15] Shen J R. Fauna Sinica, Crustacea: Freshwater Copepoda. Beijing: Science Press, 1979: 1- 450.

[16] Dumont H J, van de Velde I, Dumont S. The dry weight estimate of biomass in a selection of Cladocera, Copepoda and Rotifera from the plankton, periphyton and benthos of continental waters. Oecologia, 1975, 19(1): 75- 97.

[17] Muylaert K, van der Gucht K, Vloemans N, de Meester L, Gillis M, Vyverman W. Relationship between bacterial community composition and bottom-up versus top-down variables in four eutrophic shallow lakes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2002, 68(10): 4740- 4750.

[18] Pfister G, Sonntag B, Posch T. Comparison of a direct live count and an improved quantitative protargol stain (QPS) in determining abundance and cell volumes of pelagic freshwater protozoa. Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 1999, 18(1): 95- 103.

[19] Sime-Ngando T, Groliere C A. Quantitative effects of fixatives on the storage of freshwater planktonic ciliates. Archiv für Protistenkunde, 1991, 140(2/3): 109- 120.

[20] Sun S C, Huang Y P. Lake Taihu. Beijing: Ocean Press, 1993: 23- 89.

[21] Zhu G W. Eutrophic status and causing factors for a large, shallow and subtropical Lake Taihu, China. Journal of Lake Sciences, 2008, 20(1): 21- 26.

[22] Wiackski K, Ventelä A, Moilanen M, Saarikari V, Vuorio K, Sarvala J. What factors control planktonic ciliates during summer in a highly eutrophic lake? Hydrobiologia, 2001, 443(1/3): 43- 57.

[23] Pfister G, Auer B, Arndt H. Pelagic ciliates (Protozoa, Ciliophora) of different brackish and freshwater lakes- a community analysis at the species level. Limnologica-Ecology and Management of Inland Waters, 2002, 32(2): 147- 168.

[24] Sonntag B, Posch T, Klammer S, Teubner K, Psenner R. Phagotrophic ciliates and flagellates in an oligotrophic, deep, alpine lake: contrasting variability with seasons and depths. Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 2006, 43(2): 193- 207.

[25] Li J, Chen F, Liu Z, Xu K, Zhao B. Compositional differences among planktonic ciliate communities in four subtropical eutrophic lakes in China. Limnology, 2013, 14(1): 105- 116.

[26] Pace M L. Planktonic ciliates: their distribution, abundance, and relationship to microbial resources in a monomictic lake. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 1982, 39(8): 1106- 1116.

[27] Andrushchyshyn O P, Magnusson A K, Williams D D. Responses of intermittent pond ciliate populations and communities toinsitubottom-up and top-down manipulations. Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 2006, 42(3): 293- 310.

[28] Zhang L Y, Li K Y, Liu Z W, Middelburg J J. Sedimented cyanobacterial detritus as a source of nutrient for submerged macrophytes (VallisneriaspiralisandElodeanuttallii): An isotope labeling experiment using15N. Limnology and Oceanography, 2010, 55(5): 1912- 1917.

[29] Chen F, Chen M, Kong F, Wu X, Wu Q. Species-dependent effects of crustacean plankton on a microbial community, assessed using an enclosure experiment in Lake Taihu, China. Limnology and Oceanography, 2012, 57(6): 1711- 1720.

[30] Agasild H, Zingel P, Karus K, Kangro K, Salujõe J, Nõges T. Does metazooplankton regulate the ciliate community in a shallow eutrophic lake? Freshwater Biology, 2013, 58(1): 183- 191.

[31] Gismervik I. Top-down impact by copepods on ciliate numbers and persistence depends on copepod and ciliate species composition. Journal of Plankton Research, 2006, 28(5): 499- 507.

[32] Cheng S, Aoki S, Maeda M, Hino A. Competition between the rotiferBrachionusrotundiformisand the ciliateEuplotesvannusfed on two different algae. Aquaculture, 2004, 241(1/4): 331- 343.

[33] McCarthy M J, Lavrentyev P J, Yang L Y, Zhang L, Chen Y, Qin B, Gardner W S. Nitrogen dynamics and microbial food web structure during a summer cyanobacterial bloom in a subtropical, shallow, well-mixed, eutrophic lake (Lake Taihu, China). Hydrobiologia, 2007, 581(1): 195- 207.

[34] Archbold J H G, Berger J. A qualitative assessment of some metazoan predators ofHalteriagrandinella, a common freshwater ciliate. Hydrobiologia, 1985, 126(2): 97- 102.

[35] Hansen A M. Response of ciliates and Cryptomonas to the spring cohort of a cyclopoid copepod in a shallow hypereutrophic lake. Journal of Plankton Research, 2000, 22(1): 185- 203.

[36] Ventelä A, Wiackowski K, Moilanen M, Saarikari V, Vuorio K, Sarvala J. The effect of small zooplankton on the microbial loop and edible algae during a cyanobacterial bloom. Freshwater Biology, 2002, 47(10): 1807- 1819.

[37] Wickham S A, Gilbert J J. Relative vulnerabilities of natural rotifer and ciliate communities to cladocerans: laboratory and field experiments. Freshwater Biology, 1991, 26(1): 77- 86.

参考文献:

[6] 徐润林, Nauwerck A. 太湖北部水域的浮游纤毛虫. 中山大学学报 (自然科学版), 1996, 35 (增刊2): 100- 104.

[7] 蔡后建. 原生动物纤毛虫对太湖梅梁湾水质富营养化的响应. 湖泊科学, 1998, 10(3): 43- 48.

[8] 金相灿, 屠清瑛. 湖泊富营养化调查规范. 北京: 中国环境科学出版社, 1990: 10- 302.

[12] 章宗涉, 黄祥飞. 淡水浮游生物研究方法. 北京: 科学出版社, 1991: 1- 414.

[13] 王家楫. 中国淡水轮虫志. 北京: 科学出版社, 1961: 1- 288.

[14] 蒋燮志, 堵南山. 中国动物志 (淡水枝角类). 北京: 科学出版社, 1979: 1- 297.

[15] 沈嘉瑞. 中国动物志 (淡水桡足类). 北京: 科学出版社, 1979: 1- 450.

[20] 孙顺才, 黄漪平. 太湖. 北京: 海洋出版社, 1993: 23- 89.

[21] 朱广伟. 太湖富营养化现状及原因分析. 湖泊科学, 2008, 20(1): 21- 26.

Community structure of planktonic ciliates and its relationship to environmental variables in Lake Taihu

LI Jing1,2, DAI Xi1, SUN Ying1, SHU Tingting1, LIU Zhengwen1, CHEN Feizhou1,*, LU Wenxuan2

1StateKeyLaboratoryofLakeScienceandEnvironment,NanjingInstituteofGeographyandLimnology,ChineseAcademyofSciences,Nanjing, 210008,China2FisheriesResearchInstituteofAnhuiAcademyofAgriculturalSciences,Hefei, 230031,China

Ciliates, as a keystone microorganism in water bodies, link bacteria and phytoplankton and higher trophic levels. Accurate quantitative assessment of ciliates would lead to better predictions of material and energy flux through planktonic food web in lake systems. Ciliates were quarterly collected in 2009 at 32 sampling sites in shallow eutrophic Lake Taihu, fixed by Bouin′s solution, and stained by quantitative protargol stain (QPS). In this study, the distribution patterns of ciliate community compositions and functional groups were studied. The relationship between the ciliate community compositions and environmental variables including abiotic and biotic parameters was analyzed by canonical correspondence analysis (CCA). In the 128 samples, a total of 117 species belonging to 3 classes, 15 orders and 78 genera were found. Among the functional groups, 39 species are fallen into the bacterivorous group, represented by orders Scuticociliatida, Hymenostomatida, Peritrichida and Colpodida. Algivorous group had 25 species, mostly belonging to oligotrichids. The mixotrophic, omnivorous and predacious groups had 15, 11 and 10 species, respectively. The rest 17 species belong to the group mainly feeding on heterotrophic flagellates or are in the unclear position. The dominant species wereAskenasiaacrostomia,Balanionplanctonicum,Codonellacratera,Cyclidiumglaucoma,Halteriabifurcata,H.grandinella,Rimostrombidiumbrachykinetum,R.humile,Tintinnopsiscylindrata,Urotrichafarcta,Vorticellaaquadulciscomplex andV.campanula. Ciliate abundance ranged from 1 500 to 139 150 cells/L (mean 27 170 cells/L) and biomass from 16.7 to 8736.0 μg/L (mean 600.6 μg/L). Oligotrichids occupied 45.9% of total ciliate abundance, followed by prostomatids (34.1%), scuticociliatids (11.8%), peritrichids (3.6%) and haptorids (2.6%). The ciliate community compositions had a high heterogeneity and seasonal succession. Ciliate abundance was significantly higher in summer (August) than in other seasons. Their biomass was significantly higher in spring and autumn than in winter and summer. Generally, ciliate abundance had an increase tendency from the south part to north part of Lake Taihu, and from the pelagic area to the littoral. The small-sized species belonging to oligotrichids, scuticociliatids and prostomatids dominated the ciliate communities in the north part of Lake Taihu while the meso- and large-bodied oligotrichids species dominated in the south part. Among the functional groups, the mixotrophic taxa accounted for a substantial proportion of the ciliate assemblages in May and August. The bacterivorous and algivorous taxa dominated in the north and south parts of Lake Taihu, respectively. Unlike the above three groups, the omnivorous, predacious and the others groups only constituted a far smaller percentage of the total ciliate abundance. Results from CCA analysis showed that spatial variations of the ciliate community compositions were determined by difference factors among four seasons. The nitrogen, total dissolved carbon and chlorophyllacontent mainly determined the ciliate communities in winter. Copepod, pH, nitrate and ammonium controlled the ciliate communities in spring. The ciliate communities in summer were shaped by copepod, turbidity and dissolved nitrogen, Copepod and total dissolved carbon structured the ciliate communities in autumn. These results illustrated that both the trophic level and predation jointly shaped the ciliate community compositions in Lake Taihu.

quantitative protargol stain; Lake Taihu; ciliated plankton; biodiversity; temporal and spatial distribution; multivariate analysis

国家自然科学基金(31170440); 安徽省农业科学院科技创新团队建设(11C0505); 安徽省农业科学院院长青年创新基金(13B0528)

2012- 12- 12; 网络出版日期:2014- 03- 04

10.5846/stxb201212241852

*通讯作者Corresponding author.E-mail: feizhch@niglas.ac.cn

李静, 戴曦, 孙颖, 舒婷婷, 刘正文, 陈非洲, 卢文轩.太湖浮游纤毛虫群落结构及其与环境因子的关系.生态学报,2014,34(16):4672- 4681.

Li J, Dai X, Sun Y, Shu T T, Liu Z W, Chen F Z, Lu W X.Community structure of planktonic ciliates and its relationship to environmental variables in Lake Taihu.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2014,34(16):4672- 4681.