Efficacy Observation of Tuina Therapy for Fibromyalgia Syndrome

Zhang Kai-yong, Yang Yang, Xu Si-wei, Zhan Hong-sheng2, Zhang Bi-meng

1 First People’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai 200080, China

2 Shuguang Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai 200021, China

CLINICAL STUDY

Efficacy Observation of Tuina Therapy for Fibromyalgia Syndrome

Zhang Kai-yong1, Yang Yang1, Xu Si-wei1, Zhan Hong-sheng2, Zhang Bi-meng1

1 First People’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai 200080, China

2 Shuguang Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai 200021, China

Author:Zhang Kai-yong, master of medicine, resident

Objective: To observe the efficacy of tuina manipulations for fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS).

Methods: Sixty eligible FMS patients were randomized into two groups, 30 in each group. Patients in the observation group were intervened by tuina manipulations to the corresponding segment of the spine based on the detection of disorders of the spine-related bones and tendons; patients in the control group were directed to practice functional exercises. Before and after intervention, the fibromyalgia impact questionnaire (FIQ) and visual analogue scale (VAS) were adopted for evaluation.

Results: After intervention, the FIQ and VAS scores dropped significantly in both groups (allP<0.05), and there were significant differences between the two groups (bothP<0.05). The total effective rate was 86.7% in the observation group versus 63.3% in the control group, and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.05).

Conclusion: Spinal tuina manipulations are effective and safe in treating FMS, for significantly promoting the quality of life of the FMS patients.

Fibromyalgia; Tuina; Massage; Chiropractic; Exercise

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a type of nonarticular rheumatism, characterized by widespread pain and stiffness, accompanied by debilitating fatigue and multiple tender points, commonly seen in clinic[1]. FMS belongs to the concept of muscle Bi-Impediment syndrome in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Patients with FMS usually present sleep problems, subjective feeling of swollen extremities, numbness, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), chronic headache, and frequent or urgent urination. It’s showed that the prevalence of FMS is 0.15%-5% in population, and up 15.7% among the outpatients[2]. FMS has severely influenced the activity of daily life, and impaired the quality of life. To seek a safe and effective treatment protocol for FMS, we observed the efficacy of tuina manipulations in treating FMS. The result is concluded as follows.

1 Clinical Materials

1.1 Diagnostic criteria

By referring the diagnostic criteria of FMS stipulated by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) in 1990[3]: widespread pain lasting at least 3 months (defined as axial skeletal pain, left and right-sided pain, and upper and lower segment pain); at least 11 of the 18 (9 pairs) tender points (occiput: at the suboccipital muscle insertions; trapezius: at the midpointof the upper border; low cervical: at the anterior aspects of the intertransverse processes at C5-C7; supraspinatus at origins: above the scapular spine near the medial border; second rib: upper lateral to the second costochondral junction; lateral epicondyle: 2 cm distal to the epicondyle; gluteal: in upper outer quadrant of the buttocks in anterior fold of muscle; greater trochanter: posterior to the greater trochanteric prominence; knee: at the medical fat pad proximal to the joint line) detected by thumb pressure (with the thumb evenly and flatly pressing each point on both2side of the body, producing a pressure of 4 kg/cm).

FMS can be diagnosed when the above two items are met and other rheumatological problems are ruled out.

1.2 Inclusion criteria

Clinical manifestations conforming to the above diagnostic criteria of FMS; age between 18 and 70 years old, no gender-based limitation; willing to follow the interventions and able to wellcommunicate with the physicians and having signed the informed consent form.

1.3 Exclusion criteria

Women during pregnancy or lactation; serious diseases involving cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, liver, hematopoietic, or digestive systems, or mental disorders; a history of severe spinal trauma or surgery; spinal tumor, tuberculosis, or osteoporosis by imaging examinations; cervical spondylosis of spinal cord type; central intervertebral disc herniation.

1.4 Statistical methods

The measurement data were expressed byand analyzed by usingt-test. AP-value of <0.05 was considered as a statistical significance.

1.5 General data

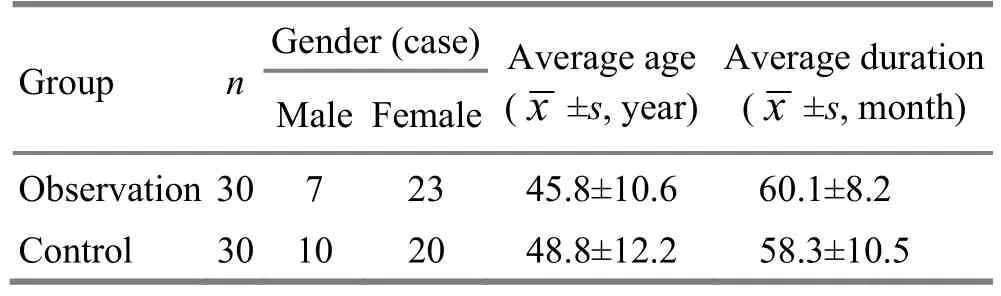

Sixty eligible outpatients of our hospital were enrolled from November 2012 to June 2013. They were randomized into an observation group and a control group, 30 participants in each group. There were no significant differences in comparing gender, age, and disease duration between the two groups, indicating the comparability (Table 1).

During the whole intervention, the attendance rate approached over 90% in both groups, suggesting a content compliance.

Table 1. Comparison of the general data

2 Treatment Protocols

2.1 Observation group

Patients were examined for the malposition of spine-associated bones and tendons before treatment to the corresponding spinal segment. Patients with cervical problems took a sitting position, and those with thoracic or lumbar problems took a lying position. The tuina manipulations were performed according to theTuina Science[4], consisting of soft-tissue relaxing manipulations and vertebral restitution manipulations.

Soft-tissue relaxing manipulations: First, thumb or palm An-pressing and Rou-kneading were performed to the soft tissues around the affected spinal segment for 10 min (Figure 1); followed by Gun-rolling manipulation on the same areas for 10 min (Figure 2); finally, thumb Tanbo-plucking was applied to the tender points in these areas for 5 min (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Palm An-pressing and Rou-kneading

Figure 2. Gun-rolling

Vertebral restitution manipulations: First, to locate and correct the disordered spinal segment according to the X-ray and palpation examinations. The located minor spinal regulation was conducted: cervical vertebrae by located oblique Ban-pulling manipulation in a sitting position (Figure 4); thoracicvertebrae by regulating manipulations in a sitting or supine position (Figure 5); lumbar vertebrae by oblique Ban-pulling in a latericumbent position (Figure 6).

Figure 3. Tanbo-plucking

Figure 4. Located oblique Ban-pulling for cervical vertebrae in a sitting position

Figure 5. Regulating manipulation for thoracic vertebrae in a supine position

The spinal tuina manipulations were performed twice a week, 30 min for each time, by the same trained physician. The therapeutic efficacy was observed after 4-week treatment.

Figure 6. Oblique Ban-pulling for lumbar vertebrae

2.2 Control group

Patients in the control group performed functional exercises, twice a day.

Cervical exercise: Six directions of cervical movements included anteflexion (Figure 7), backward extension (Figure 8), lateroflextion to left and right side (Figure 9), and rotation to left and right side (Figure 10). For each movement, a 3-second pause was required at the maximum motion range. Then the shoulders were rotated forward and backward, 10 times for each direction (Figure 11).

Figure 7. Anteflexion of cervical vertebrae

Figure 8. Backward extension of cervical vertebrae

Figure 9. Lateroflexion of cervical vertebrae

Figure 10. Rotation of cervical vertebrae

Figure 11. Rotation of shoulder joints

Thoracic and lumbar exercises: In a supine position, the patient lifted both lower extremities together as high as possible while keeping the knees straight, pausing for 5 s, and then slowly put them down (Figure 12). When sitting on a bed, with the two legs placing on the bed and straight knees, the patient bent his waist to hold the far-ends of the lower extremities, then raised up his head by 45°, holding this position for 5 s, and then released (Figure 13). The above two movements were performed 3 times every morning and night. The therapeutic efficacies were observed after successive 4-week exercises.

Figure 12. Straight-leg lifting in a supine position

Figure 13. Leg-stretching and waist-bending in a sitting position

3 Observation of Therapeutic Efficacies

3.1 Observation indexes

3.1.1 Fibromyalgia impact questionnaire (FIQ)

FIQ is used to evaluate the physiological function, general condition, and living condition of FMS patients. Its score range is 0-100, the higher the score, the more serious the problem.

3.1.2 Visual analogue scale (VAS)

VAS reflects the pain severity. Took a 10 cm rope, and marked the two ends with 0 and 100, 0 for no pain, and 100 for extreme pain. The patient marked on the rope according to his pain severity, and the researcher recorded the corresponding score.

3.2 Criteria of therapeutic efficacy

The activities of daily living and subjective feelings of the patients (such as pain, fatigue, stiffness of muscle, and emotion) were taken into the calculation of the total score of FIQ and VAS. Nimodipine method was adopted to calculate the reduction rate. Thecriteria of therapeutic efficacy in the study were based on the score ratio and the relevant criteria for muscle Bi-Impediment from theCriteria of Diagnosis and Therapeutic Effects of Diseases and Syndromes in Traditional Chinese Medicine[5].

Reduction rate = (Total pre-treatment score -Total post-treatment score) ÷Total pre-treatment score × 100%.

Marked efficacy: Major symptoms such as pain and sleep disturbance were gone, and the reduction rate>50%.

Effective: Major symptoms such as pain and sleep disturbances were improved, and the reduction rate≥25%, ≤50%.

Invalid: Major symptoms such as pain and sleep disturbances were not improved, and the reduction rate <25%.

3.3 Results

3.3.1 Comparison of FIQ

Before intervention, there was no significant difference in comparing the FIQ score between the two groups. The FIQ scores were significantly changed after intervention in both groups (bothP<0.05), indicating that the quality of life was improved in both groups; the inter-group difference was statistically significant after intervention (P<0.05), suggesting that the improvement of the quality of life in the observation group was more significant than that in the control group (Table 2).

3.3.2 Comparison of VAS

Before intervention, there was no significant difference in comparing the VAS score between the two groups. After intervention, the VAS scores were significantly changed in both groups (bothP<0.05), indicating that both groups had improvement in pain; there was a significant difference between the two groups after intervention (P<0.05), suggesting that the observation group had a more significant improvement in pain compared to the control group (Table 3).

Table 2. Comparison of FIQ before and after interventionpoint)

Table 2. Comparison of FIQ before and after interventionpoint)

Note: Intra-group comparison, 1) P<0.05; compared with the control group after intervention, 2) P<0.05

?

Table 3. Comparison of VAS before and after interventionpoint)

Table 3. Comparison of VAS before and after interventionpoint)

Note: Intra-group comparison, 1) P<0.05; compared with the control group after intervention, 2) P<0.05

?

3.3.3 Comparison of general efficacy

The total effective rate was 86.7% in the observation group versus 63.3% in the control group, and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.05), suggesting that the therapeutic efficacy of the observation group was higher than that of the control group (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of the general therapeutic efficacy (case)

4 Discussion

FMS is diagnosed based on nine pairs of tender points distributed in the four quadrants taking the spine as the axis. In TCM, FMS falls under the scope of malposition of bones and tendons. Manipulations, including relaxing manipulations for soft tissues and correcting manipulations for spine, can restore the normal physiological function of spine and the involved nerves. According to anatomy, the manipulations possibly treat FMS via correcting the disorders of the micro-articulations and synovium of spine, relieving spasm of the muscles beside the spine, and promoting the absorption of inflammatory mediators.

The malposition of bones and tendons is the footstone of the existence and development of tuina manipulations, and also the common targets in tuina treatment. The malposition of spine-related bones and tendons can lead to the corresponding symptoms all over the body[6-8]. The movement of spine depends on the coupled movements of several motor units of spine. Each motor unit consists of two spinal vertebrae and their joint part. Slight change of any component of the motor unit will ultimately cause the alteration of loading distribution on the triple-joint complex (the composite joint consisting ofthe intervertebral disc and the bilateral zygapophyseal joints). This biomechanical change will lead to various symptoms[9-10].

Spine is in the pathways of the Governor Vessel and Bladder Meridian. The Governor Vessel is in charge of the yang energy of the back and all yang meridians. As the Governor Vessel runs inside the spine and connects to the brain, so the kidney, spinal cord, and brain are believed to be as a whole. Tuina manipulations applied to the Governor Vessel and Bladder Meridian can activate all the meridians. When the Meridians of Liver, Spleen, and Kidney are functioning well, the smooth qi activities, sufficient blood, and strong tendons and bones will make the spine to play its role well. The current study shows that spinal tuina manipulations can finally harmonize tendons and bones by regulating and unblocking meridians and collaterals, correcting the malposition of tendons, and circulating qi and blood[11-12]When the bones are in right positions and tendons are flexible, and the relevant muscles and soft tissues are relaxed, the symptoms of FMS can be reduced. This treatment is effective and easy-to-operate, causing no pain to patients, and thus is worth applying in clinic.

Conflict of Interest

There was no conflict of interest in this article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Third Construction Project of Traditional Chinese Medicine Clinical Advantage Special Department (Special Disease) of Shanghai; Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Foundation Project of Shanghai Health Bureau (No. 2010J007A); Famous Traditional Chinese Medicine Doctor Construction Project of Yan Jun-bai’s Academic Experience Work Room (No. ZYSNXD-CCMZY023); Shanghai Training and Construction Project of the Shortage Personnel of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

[1] Zhang NZ. Clinical Rheumatology. Shanghai: Shanghai Science and Technology Press, 1999: 400-404.

[2] Neumann L, Buskila D. Epidemiology of fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep, 2003, 7(5): 362-368.

[3] Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, Tugwell P, Campbell SM, Abeles M, Clark P. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum, 1990, 33(2): 160-172.

[4] Yu DF. Tuina Science. Fifth Edition. Shanghai: Shanghai Science and Technology Press, 1985.

[5] State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Criteria of Diagnosis and Therapeutic Effects of Diseases and Syndromes in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Nanjing: Nanjing University Press, 1994: 49-50.

[6] Gong WZ, Wang YQ. Observations on the therapeutic effect of acupuncture on fibromyalgia syndrome. Shanghai Zhenjiu Zazhi, 2010, 29(11): 725-726.

[7] Schafer RC, Faye LJ. Motion Palpation and Chiropractic Technic: Principles of Dynamic Chiropractic. Huntington Beach: The Motion Palpation Institute, 1989: 15.

[8] Fang M, Sun WQ, Yan JT. Two cases of fibromyalgia treated with three-step tuina manipulations plus exercises. Anmo Yu Daoyin, 2006, 22(9): 27-29.

[9] Huang F, Chen X, Mu JP. Clinical study on extracorporeal shock wave therapy plus electroacupuncture for myofascial pain syndrome. J Acupunct Tuina Sci, 2014, 12(1): 55-59.

[10] Gao MX, Wang J. Tongdu massage treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome the clinical research and appraises. Harbin: Master Thesis of Heilongjiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2010.

[11] Chen R, Zeng QY. Fibromyalgia syndrome. Zhongguo Jiceng Yiyao, 2000, 7(6): 443-444.

[12] Li YH, Wang FY, Feng CQ, Yang XF, Sun YH. Massage therapy for fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PloS One, 2014, 9(2): e89304.

Translator: Hong Jue

Zhang Bi-meng, M.D., associate professor, associate chief physician, mentor of master degree candidate.

E-mail: pjzhtiger08@aliyun.com

R244.1

: A

Date: July 18, 2014

Journal of Acupuncture and Tuina Science2014年6期

Journal of Acupuncture and Tuina Science2014年6期

- Journal of Acupuncture and Tuina Science的其它文章

- Personal Experience on Palpation of the Spine

- Tuina plus Ultrasonic Therapy for Infantile Muscular Torticollis

- Warm Needling Moxibustion at Zhongji (CV 3) and Zusanli (ST 36) for Urinary Retention after Gynecological Surgery

- Acupoint Massage in Relieving Pain after Ureteroscopic Holmium Laser Lithotripsy

- Therapeutic Efficacy Analysis of Balancing Yin-yang Manipulation for Post-stroke Upper Limb Spasticity

- Therapeutic Efficacy Observation on Acupoint Sticking for Edema Due to Chronic Cardiac Failure