Yang Meng:The Worker

by+Yin+Xing

Born in 1986, Yang Meng grew up in Chunjing Village of Yibin City, Sichuan Province. When he was at second grade, his parents took his younger brother with them as they left home to work, making the elder son a“left-behind child.”

“When I was living in the village alone, I bounced around the homes of my aunt, uncle and granny.” Thanks to money borrowed from relatives, Yang finished high school. After graduation, he worked as a photographer in a local photography shop. In 2007, lacking decent job prospects in his hometown, Yang left for Shenzhen – and a migrant workers left-behind child became a secondgeneration migrant worker.

“Troublemaker”

“Shenzhen is the pioneer of Chinas reform and opening up; I thought I could find a position there,” explains Yang. At the time, Yang had developed his own ‘five-year plan. “I hoped that in five years, I could pay off my debt and save enough money to open a photography shop in my hometown.”

Reality is always crueler than hope. Due to his parents work experience, Yang thought he knew of the hardships of being a migrant worker, but reality still exceeded his expectations. A factory that hired Yang produced auto parts and often required employees to work overtime. Sometimes, Yang was so tired that he would even “fall asleep while walking and eating.”

However, worse than physical exhaustion, lack of respect hurt him more. Once because of mechanical failure, a workers fingers got stuck in a machine. It was urgent to get his fingers out. “Instead of rushing him to a hospital, the foreman checked the machine and asked ‘whats wrong with the machine?” Yang recalls. “He was more worried about the equipment than the workers fingers. He was only afraid that the problem would affect production.” This accident made a strong impact on Yang. “We are human beings. Arent we more important than machines?”

Since then, Yang decided not to tolerate injustice. He started reading legal books related to labor contracts and workers rights in his spare time. With his newfound legal knowledge, Yang began arguing with bosses. He rejected overtime and delayed payment, and asked for improved working conditions as well as basic social insurance. Gradually, in the managements eyes, he became a troublemaker.

When he resigned from the job, Yang continued standing up tall to the management. The factorys rules stipulated that an employee should notify the factory one month before resigning. Since Yang left without any notice, the factory refused to give him his final pay. “The manager had a security guard threaten me,” he recounts. “However, any one of the complaints I had brought to them should allow me to resign legally.” Yang contacted the Labor Inspection Team of the Labor Bureau to complain of the plants safety problems, delayed payment and lack of employee insurance. After playing this card, management quickly handed over his final check and Yang left quietly.

Mentor

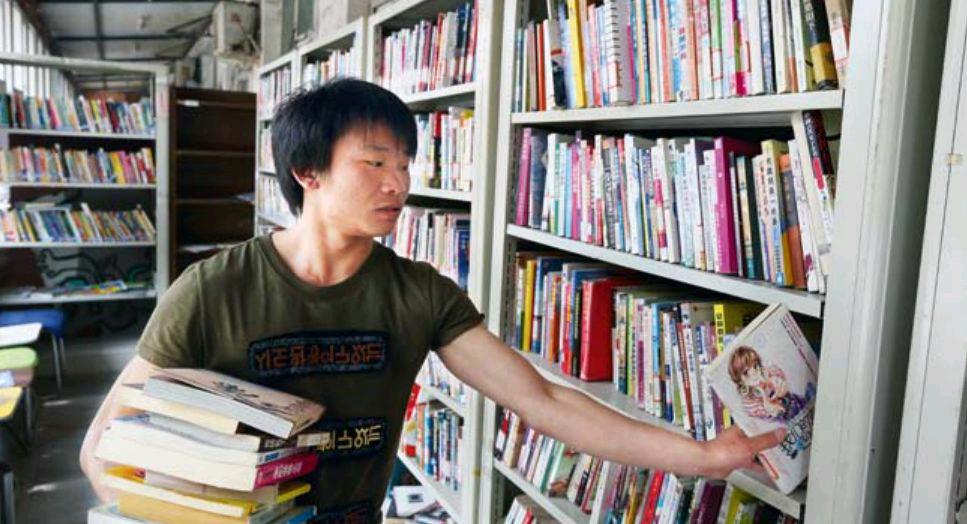

While in Shenzhen, Yang volunteered to help with legal education for a charity dedicated to aiding migrant workers. After he quit his job, Yang traveled to Suzhou and Xian to join local nonprofit organizations. He worked in local factories for a short time in order to familiarize himself with workers situations, and then taught law to them.

In 2009, Yang became a student in the training center of Beijing Workers Home, also a non-profit organization. Later he became a member of the team, responsible for managing their website and legal training for migrant workers.

“At first, I just relayed my limited legal knowledge and past experience,” he admits. “I just told them to do what I did.” Gradually, Yang found these methods had become ineffective. When some were injured or denied salary and Yang volunteered to help, the workers considered him na?ve and hardly aware of the cruelty of the situation. “Away from their hometowns, they always think its just better to avoid confrontation.” Although his help did work for some, “they were grateful, but they didnt pass it on to anyone else.”

“It” in Yangs words refers to “a kind of awareness.” For an individual worker, it is awareness to fight for rights and personal safety. For a group of workers, it is the awareness to help each other. “For example, when I mentioned occupational conditions and injuries, many workers thought I was telling them to avoid certain jobs,” illustrates Yang. “Everyone wants to be a bystander. We are a huge group – about 250 million – yet we have no power or voice.” In order to raise their awareness, Yang gathered more cases which the workers would take personally. “I expanded occupational injuries to include industrial pollution, toxins and other possible damage to personal health,” he remarks. “And then they felt more connected to the present situation.”

Actually, Yang did find some new awareness in his peers, which the migrant workers of his fathers generation sorely lacked.“Twenty years ago, my fathers hands alone could support the whole family but now my work can hardly feed myself,” Yang explains. “But in my fathers generation, they worked in horrific conditions for decades without a hint of complaint. We are different. We keep changing jobs and pursuing better lives. And our awareness is growing during the process.”

Loving Life

After becoming a volunteer, Yang could avoid back-breaking work, the threat of injury and humiliation from managers. Although his situation has changed, as a migrant worker, his uncertainty about the future remains. “Our fathers, they first did farm work before leaving for work, so they remain rooted in rural areas,” Yang explains. “They have social networks in their hometowns. So, they go back home to celebrate Chinese New Year and attend weddings and funerals. They find sense of belonging there.”Yangs generation is different. They never made a living by farming. “The farmland in rural areas is limited. I cannot support myself by farming. People leave to work, so villages are disappearing and rural pollution is becoming worse. In cities, our employment rights, residency, and our childrens educational rights cannot be guaranteed. We lack security.”

As Yang struggles in limbo between country and city, he is hesitant to define his group. “On one hand, our labor hardly enables us to make ends meet. On the other hand, our hands make China the global processing factory, providing clothes, daily necessities and even food to the whole world. Do we matter at all or not?”

Yang looks for his own answers. “During our toils, we will find new awareness of the value of our labor and lives, and then we will discover answers,” he believes. “The answers exist in our labor and life.”

Yang doesnt complain about his situation. “There are no desperate situations but only desperate people. More torture from life, more love for life.”

China Pictorial2014年5期