Howl to Hutongsters

by+Scott+Huntsman

“Forget the wrecking ball,” wrote Lee Hannon in China Daily in 2011.“Beijings historic hutong need saving not from the demolition crew but from the ever-increasing number of Western hipsters who believe they are living the latest vogue.”

The British-born editor at China Daily went on to coin the term “hutongster” as he lambasted hipster subculture as the worst plague to hit Beijing as if air quality and traffic were their fault. Some Beijing practitioners of the movement rooted in American cities have already embraced the intended pejorative not unlike the Britishcoined former insult, “Yankee”.

Indeed, the group known today as“hipsters” ranks amongst the most lamented demographics in the West, and few admit membership even when they fit every criterion to a tee. Hipsterism is most often associated with young urbanites who like indie music and vintage or thrift-shop-purchased clothing, but a third defining trait is fondness for gentrification – one that makes Beijings hutong hipsters, some of which in-habit dwellings as old as the Yuan Dynasty(1271-1368), some of the hippest around– perhaps the factor making Beijings mainstream expat “squares” such as Hannon so terrified. Since the word “hip” began being used as an adjective decades ago, hipsters have tended towards self-imposed poverty and Bohemian lifestyles, so it should be no surprise to see them drawn to what could have become Beijings ghettos.

Hannon called the trend a “passing fad,” apparently ignorant of the subcultures roots in 1940s jazz, not to mention literature and poetry of Beat Generation writers such Jack Kerouac and Alan Ginsberg. Three years after Hannons“hutongster” editorial, the hipster presence in Beijings Gulou area, characterized by traditional hutong alleyways surrounding the historic Drum and Bell Towers, is only stronger and more glaring. Graffiti art ripped from Los Angeles freeway ramps graces formerly vanilla shop hoods and kitschy shops pop up one after another. Critics are quick to attack the hypocrisy of adherents: They claim to seek a more authentic China experience, yet Gulou is now suspiciously Beijings hotbed for gourmet burgers. Overpriced vintage shops line Gulou East Street, and some of the capitals best eateries for high-end Western food are tucked away in 500-year-old alleys, charging prices 10 times as much as their traditional Chinese counterparts next door.

In one hutong compound just inside what was formerly Beijings ancient city wall, a Chinese property-owner recently refurbished three apartment units, installing toilets and showers for the first time. The units instantly rented to three different foreign tenants, and the lane welcomed its first non-Chinese residents ever. Most inhabiting this particular nook still lack private plumbing, bathe out of bowls and walk outdoors in pajamas to use public restrooms, while their new foreign neighbors enjoy almost every modern amenity.“Ive lived in Beijing for several years, and this apartment is exactly what I always wanted,” reveals American hutong resident Josh Wilson. “Otherwise, youre living in a massive concrete apartment block and scaling four flights of stairs every day. Now, I walk out my ground-floor door into a traditional, centuries-old alley with tons of character. When I excitedly posted pictures of the new place on social media, many of my Chinese friends thought I was complaining when I was actually bragging. Really, the only drawback to living here is a bad smell from the drains sometimes, so I can understand why lacking indoor plumbing actually has at least one benefit.”

Other, even braver foreign-born hutong residents endure shared toilets and a lack of winter heating, while others live in relatively modern familiar massive apartment blocks which have been constructed amidst surviving hutongs.

A stereotypical hipster is educated, but holds a liberal arts degree – perceived as fairly worthless back home – but good enough to teach English in China. The central location of the hutong area is ideal for teachers employed by private schools which require commuting to a variety of locations (as opposed to those who work at a single institution and live in on-campus housing provided by the employer). Like those inhabiting metropolitan areas around the world, other hipster-types in the Beijing scene are often employed in music, art, media and fashion industries.

Gentrification has been debated extensively, especially in Beijing, but due to a general Chinese disdain for outdated, impractical infrastructure they endured for so long, many locals would have no problem with bulldozers wiping out the last of the old city to make way for modern structures and amenities, so its tough to measure the foreign impact on the preservation of Beijings relics – or their destruction. Many argue that inhabiting a refurbished hutong abode is as authentic as living in a McMansion, despite the fact that a few fossils of the past and half-millennia-old maps are preserved in the process.

“Hipsterism is often dismissed as an image by some, but the culture as a whole is effecting changes in society, leading to feelings of insecurity and resentment in people who are no longer a part of the cultural ruling class,” wrote Trey Parasuco in a supportive 2007 definition of “hipster”.

Indeed, as the “cultural ruling class”continues gentrifying hutongs, the “squarer” foreign Beijing residents who still live in eastern districts around the embassies are beginning to creep westward towards central hutongs. Sanlitun, the foreigner-haven for decades serving the drinking needs of embassy staffers, continues a decline into staleness compared to the younger vibrant character of the hutong renaissance.

Beijings foreign residents number barely over 100,000, so their influence on the city is still negligible without support from the tens of millions of Chinese resi- dents, and the quantity of Chinese “hutongsters” clearly already outnumbers their foreign counterparts. The Diplomat reported in April that gentrification in Wudaoying Hutong – one cornerstone of both hutong and hipster communities – is unique in that its biggest influence comes from domestic Chinese tourists. “The owners of two vintage stores opened in the past year, both Beijingers and in their 30s, observed that the majority of their clientele was Chinese, and cited Golden Week [Chinese National Day Holiday] as their busiest time,” wrote Margaux Schreurs. “Other storeowners held similar views, claiming domestic trade as their main source of revenue.”

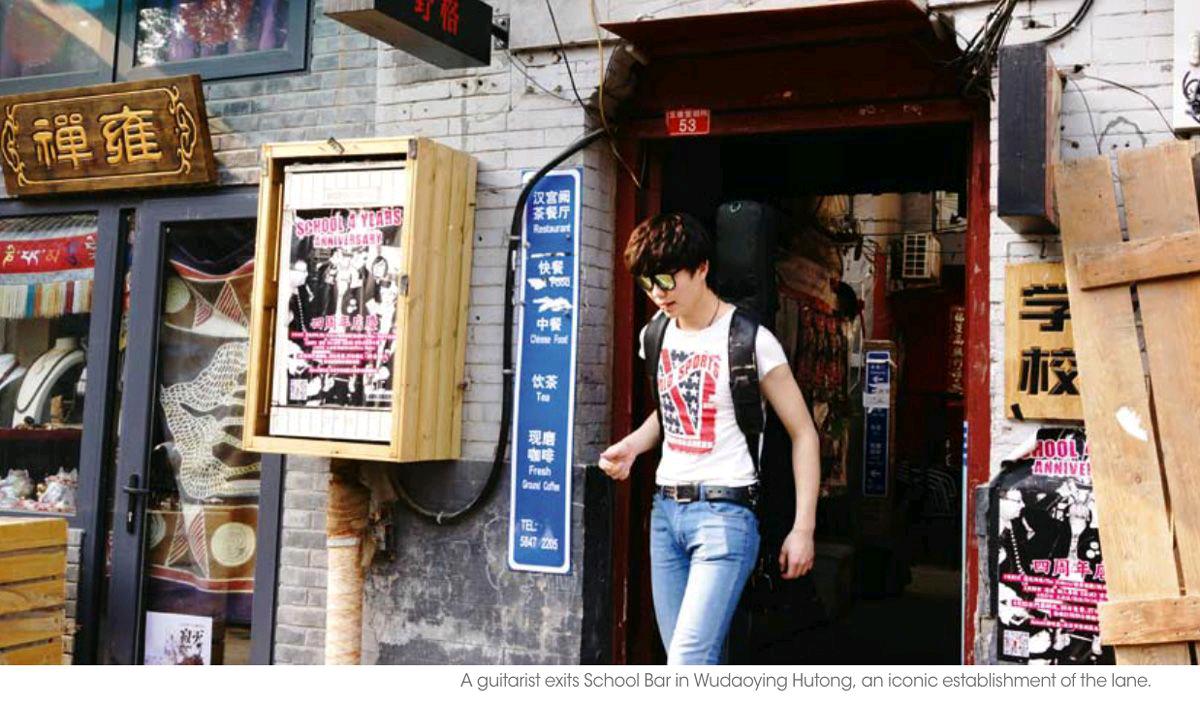

Even if most of the money flowing into Wudaoying Hutong now comes from Chinese tourists, the first business to settle in the lane was Vineyard Cafe, a foreignoperated pasta restaurant and wine bar. Another key tenant is School Bar, a small live music venue operated by the former bassist of Beijing punk band Joyside. As proprietors enjoy the influx of tourist cash, locals both foreign and Chinese lament the invasion and begin transitioning their consumption elsewhere – now to Fangjia and Beiluoguxiang hutongs – before they too lose all authenticity and become other Nanluoguxiangs (an extremely over-gentrified hutong which is now one of Beijings most popular tourist attractions). Despite any influence by local residents, perhaps the inescapable fate of all Beijing hutongs is becoming like Disneyland rides through ancient China.

Ultimately, the presence of subcultures such as hipsters only testifies to Beijings increasing status as a world-class city capable of rivaling New York, Paris, and London – regardless of ones personal feelings about the group. Because some Brooklyn hipsters once decided to wear tattered old jeans, today, even the squarest of squares likely own pants designed to appear older than they are. Lee Hannon compared Beijing hutongsters to Londons yuppies of the 1980s, but such a dated and insulated reference reveals ignorance of the continuing profound influence of the “vile species” on global culture.