Validating “Look, Listen, Feel” for practical communications in the Emergency Department

Chua Shu Min Joanne, Fatimah Lateef

1Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland

2Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital

Validating “Look, Listen, Feel” for practical communications in the Emergency Department

Chua Shu Min Joanne1, Fatimah Lateef2*

1Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland

2Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital

Objective: To test the usefulness of the LLF model as a communication-training tool. Methods: This study was carried out in the Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital on 67 healthcare personnel, consisting of doctors, nurses, allied health workers and medical students. Participants filled in a pre-LLF-model questionnaire that would elicit information pertaining to communications training. An oral presentation of the LLF model was then delivered and participants had 2 weeks to test the model in their daily practice. A post-LLF-model questionnaire was later administered to the participants, requesting feedback on the usefulness of the LLF model. Results: Out of 67 participants who were taught the LLF model, 53 participants graded the model on average, 4.2 out of 5 points. 5 points indicated the highest level of usefulness.

Conclusions: The results show promising response to the LLF model of communications, hence providing a rationale to advance this model.

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Received 14 March 2014

Received in revised form 25 June 2014

Accepted 25 July 2014

Available online 20 November 2015

Emergency department

Communications

Look

Listen

Feel

Survey

1. Introduction

In the healthcare setting, communication is multifaceted. Health care staff interacts with other healthcare staff, police, security, patients, their relatives, administrative staff and more. There is a constant influx of information jousting for the healthcare worker’s attention. This may result in sharp and curt interchanges leading to inadequate communication, miscommunication or even non-communication[1,2]. The mix of disruptions and numerous concomitant duties may also result in clinical discrepancies as healthcare workers are juggling a lot on their minds[3].

The means of communication in healthcare have also evolved beyond interpersonal interactions to the widespread use of technology to exchange information. Telemedicine has received exponential interest since the 1990s and can range from the simple use of the telephone and emails to transmit data, to distant computerized clinical consultations[5,6]. While technological modalities improve communications in terms of efficiency and accessibility, over-reliance on electronic devices may compromise on interpersonal skills and natural human rapport[2,5].

A study conducted on communication loads in two emergency departments in New South Wales, Australia found that 90% of information exchanges still involved interpersonal dealings[4].

Another study conducted in the United States of America compared data from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) in 2003 to 2005 and showed that despite evidence that the public desired internet-based avenues to approach healthcare personnel, the actual participation in patient-healthcare worker communication has been low[6]. Hence improving communication via training necessary personnel can prove to be more beneficial for patient care rather than remodeling information processes[3].

Improving communications in all healthcare staff will benefit patient care; however targeting doctors may reap the most benefit. Doctors are singled out by a majorityof patients for being their primary source of information, according to a study carried out on patients leaving the emergency department in Bakersfield, California[7]. Another investigation carried out by the McGill University Health Centre in Canada elicited how effective listening of doctors benefitted their patients by improving diagnosis, being a form of therapy and fortifying the doctor-patient relationship[8].

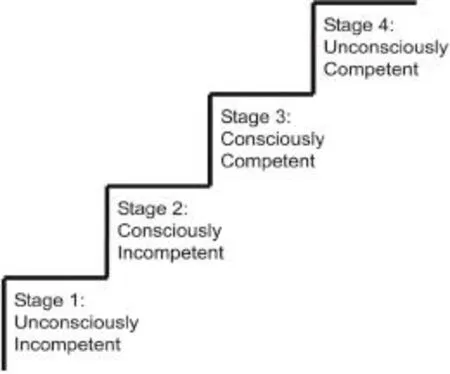

The “Look, Listen and Feel” (LLF) model is developed as a tool to aid communication training. It has an uncomplicated framework that can be adjusted to custom-fit different specialties and is applicable to healthcare worker-patient relationships and inter-healthcare worker relationships alike. In line with the Conscious Competence Learning Model[9] (Figure 1)[10], the LLF model pushes healthcare workers to first become aware of deficiencies in their communication attitude.

Then they are stimulated to consciously work on their communication skills until good and effective communication becomes second nature. The LLF model functions as a good communication-training tool because it is short and easy to remember, summarizing essential attitudes of communication into three letters. Lengthy lists taught may be readily forgotten.

Figure 1. Conscious competence learning model[10].

The phrase ‘Look, Listen and Feel” is universally ingrained amongst doctors and nurses as part of their Basic Cardiac Life Support (BCLS) or Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) courses[11]. Built on this well-known phrase, the LLF model is a pseudonym to an already familiar expression.‘Look’ reminds healthcare providers that communication is a two way process. They have to look and recognize the body language of their patients, at the same time be aware that their patients are looking back at the provider’s nonverbal cues and deciding on the provider’s level of interest in them[2]. ‘Listen’ reminds healthcare providers not to fire questions at their patients, but to allow their patients to tell their own story in their own words[2]. ‘Healthcare providers are also reminded to actively absorb what their patient is saying instead of formulating the next question in their minds. The patient’s story in full may contain clues leading to more solid and exact diagnoses[2,8]. ‘Feel’ reminds the healthcare provider to be conscious about the emotional plight of patients and to actively indicate to them that their concerns are understood[2]. By taking a mindful effort to understand the patient’s viewpoint, providers themselves can also lessen their own frustration when dealing with difficult patients.

This study aims to put the LLF model into actual practice in the emergency department and obtain feedback on its feasibility. Secondary aims include using a questionnaire to find out how many aspects of communication a healthcare worker deals with on average and whether participants feel that they have had sufficient communication training to date. The questionnaire will also evaluate the participants’desire to attend communication training courses and their satisfaction with their current level of communication capabilities.

2. Materials and methods

The emergency department (ED) was chosen as a starting point to put the “Look, Listen and Feel” (LLF) model to test because the ED is one of the faster-paced disciplines whereby sub-quality communications are prone to occur. Our sample population comprised of doctors, nurses, allied healthcare workers and medical students who rotated in the ED.

The doctors comprised of doctors specializing in emergency medicine and also in other specialties including internal medicine, psychiatry, anesthesia, pediatrics and general surgery.

The nurses comprised of those working in the emergency department and ranged in their years of experience from 1 year to 20 years. The allied healthcare workers included dieticians and patient-care assistants. The medical students comprised of those doing an elective in the ED at the point of time when the study was being carried out.

In this particular study, the LLF model was taught in the context of improving doctor-patient relationships, however the model is also applicable to inter-healthcare worker relationships and other facets of communication. We made use of doctor-teaching sessions and nurse-handover periods to administer the questionnaires and deliver the LLF model. First, participants were allowed five minutes to fill up the pre-LLF-model questionnaire, and then a ten-minute oral PowerPoint presentation of the LLF model was presented. Participants were then encouraged to apply the LLF modelin their daily practice for the following two weeks. After two weeks, the participants filled in a post-LLF-model questionnaire, which was designed to fulfill our primary aim of determining the usefulness of the LLF model (Table 1).

The pre-LLF-model questionnaire was designed to fulfill our secondary aim of determining whether participants felt that healthcare communication needed improvement and if they desired communication training (Table 2).

All questionnaires were anonymous hence increasing the honesty and validity of the data received. Any ethical issue with regard to being able to link a questionnaire to a participant was hence also eliminated. Only two peopleusing the same PowerPoint slides and script delivered the LLF model oral presentation. This ensured consistency in the material taught to all the participants.

Table 1. List of questions in the post-LLF-model questionnaire.

Table 2. List of questions in the pre-LLF-model questionnaire.

All the data collected were compiled and analyzed by one investigator using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. This reduced irregularities in interpreting the questionnaire results. The compiled data was then double-checked and approved of by the other investigator.

3. Results

A total of 67 participants who completed the pre-LLF-model questionnaire and were taught the LLF model were split into five sub-groups (Table 3): Doctors specializing in emergency medicine (DREM), Doctors from other specialties (DRO), Nurses (NR), Allied health workers (AH) and Medical students (ST). For some data, AH and NR are collectively considered as one group due to their questionnaires being collected together.

Table 3. Breakdown of total participants (67) who were taught the LLF model.

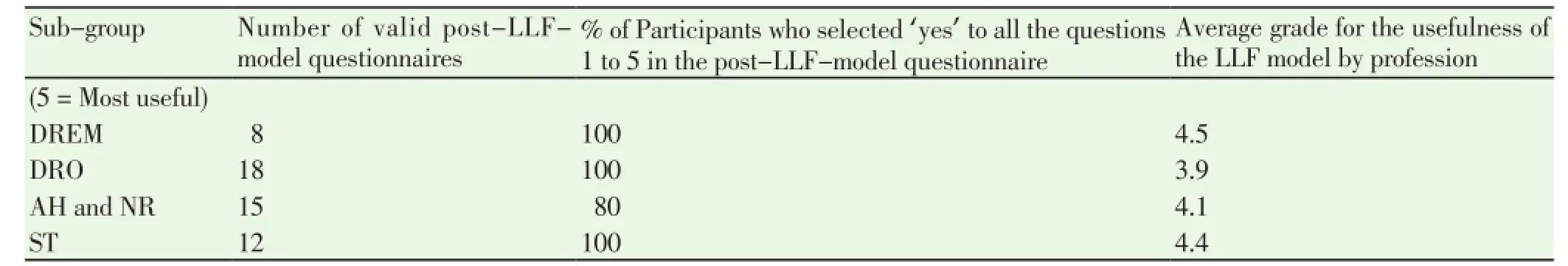

Analysis of the post-LLF-model questionnaire (Table 4) showed that 100% of the DREM, DRO and ST participants felt that they would be able to apply the “Look, Listen and Feel” (LLF) model in their communication process and that the model helped them to recall the important aspects of communication.

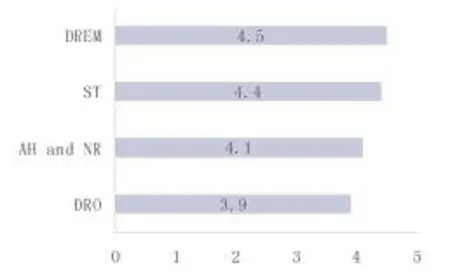

The same groups also felt that the LLF model increased their communication confidence and that they would be able to share the LLF concept with other people. NR and AH collectively had 80% participants who selected ‘yes’ to all the questions 1 to 5 in the post-LLF-model questionnaire. Each sub-group on average graded the LLF model 4.2 out of 5 points, with 5 points being the highest level of usefulness. DREM found the LLF model to be the most useful, followed by ST, then AH and NR collectively and finally DRO (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Usefulness of the LLF model according to each profession (5 points being the most useful).

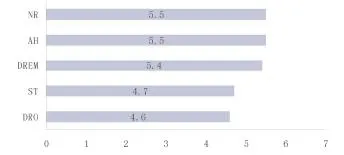

Analysis of question 2 of the pre-LLF-model questionnaire showed that NR and AH were involved with the highest number of aspects of communication at work, both at 5.5 out of 7 listed aspects. This is followed by DREM at 5.4, ST at 4.7 and DRO at 4.6 aspects of communication (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Average number of aspects of communication each profession is involved in at work (Out of 7 listed aspects).

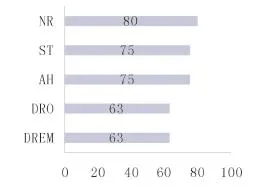

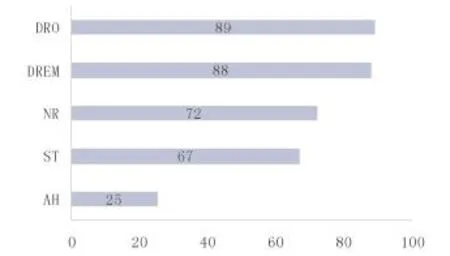

Analysis of question 3 the pre-LLF-model questionnaire revealed that more than half of all the participants had already attended a communication-training course. NR had the highest number of participants at 80%, followed by ST and AH at 75%, and DRO and DREM at 63% (Figure 4).

Table 4. Analysis of the post-LLF-model questionnaire.

Figure 4. Percentage of participants who have attended a communication-training course (%).

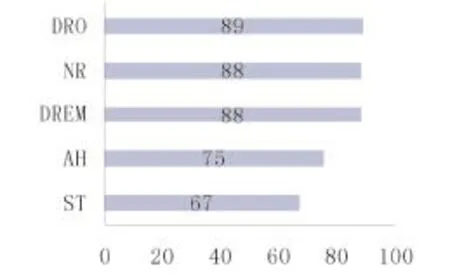

Figure 5. Percentage of participants who would like to attend a communication-training course (%).

Analysis of question 4 of the pre-LLF-model questionnaire showed that the percentages of participants who desired to attend a communication-training course exceeded the percentages that have already received prior communication training for each sub-group.

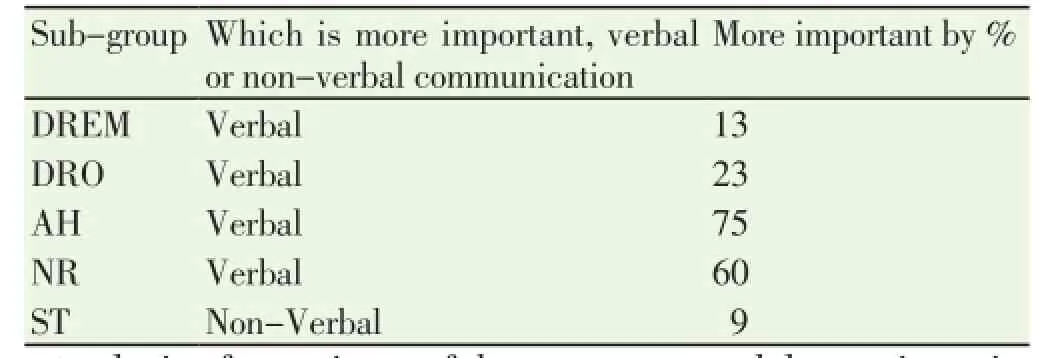

Analysis of question 5 of the pre-LLF-model questionnaire revealed that all sub-groups felt verbal communication to be more important than non-verbal communication, except for the medical students (ST) (Table 5). Table 5 also lists the percentage by which verbal communication received more votes than non-verbal communication for groups DREM, DRO, AH and NR. The importance of nonverbal communication received 9% more votes than verbal communication in the ST group.

Table 5. Participant’s feedback on which is more important, verbal or nonverbal communication.

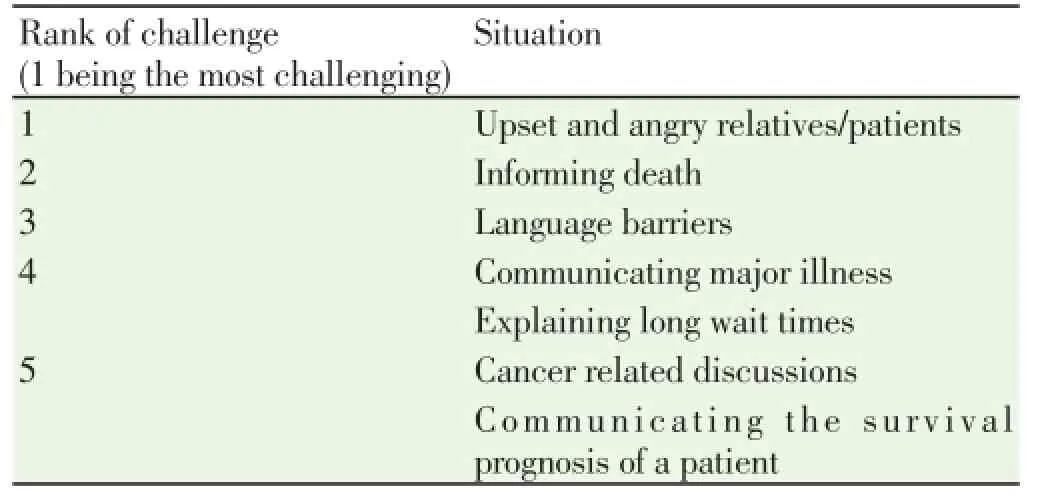

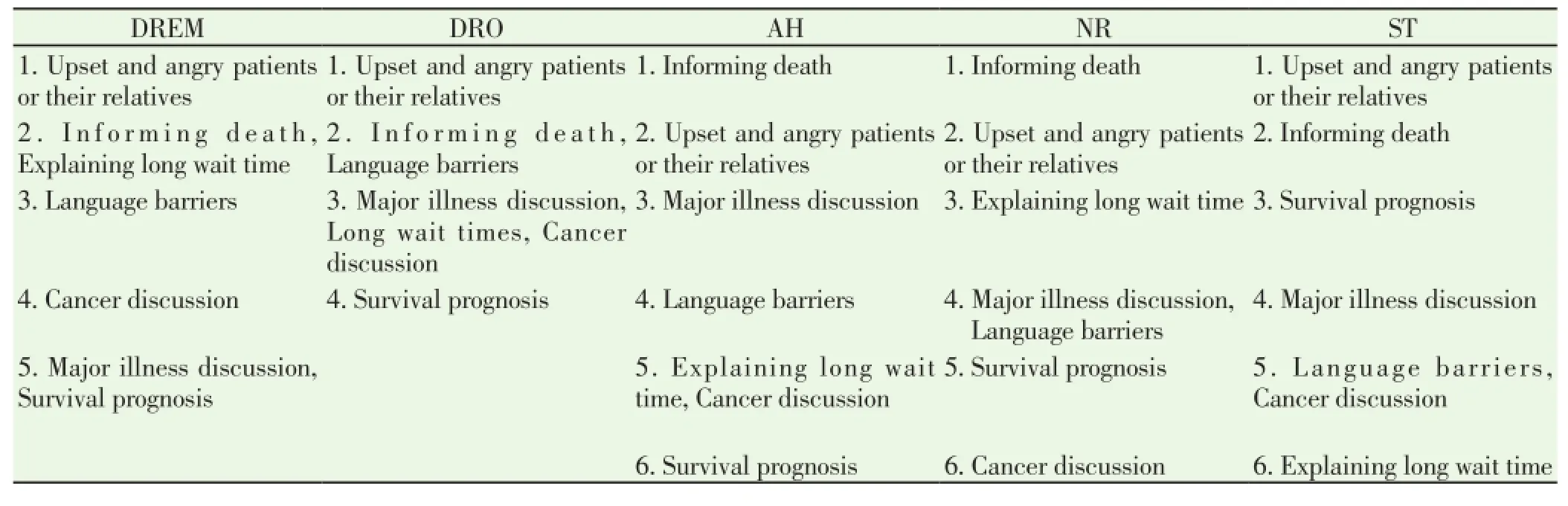

Analysis of question 6 of the pre-LLF-model questionnaire showed the order of situations that participants on average found the most challenging (Table 6). A breakdown of the situations ranked by each profession is shown in Table 7. Some situations tied for the same rank.

Table 6. Situations in order of challenge (An average of all participants).

Analysis of question 7 of the pre-LLF-model questionnaire showed that majority of the sub-groups felt stress or fear when they had to break bad news except for AH. (Figure 6) DRO was noted to feel the most stress or fear, followed byDREM, NR, ST and then AH.

Table 7. Situations in order of challenge (A breakdown of each profession).

Figure 6. Percentage of participants who feel stress or fear when breaking bad news (%).

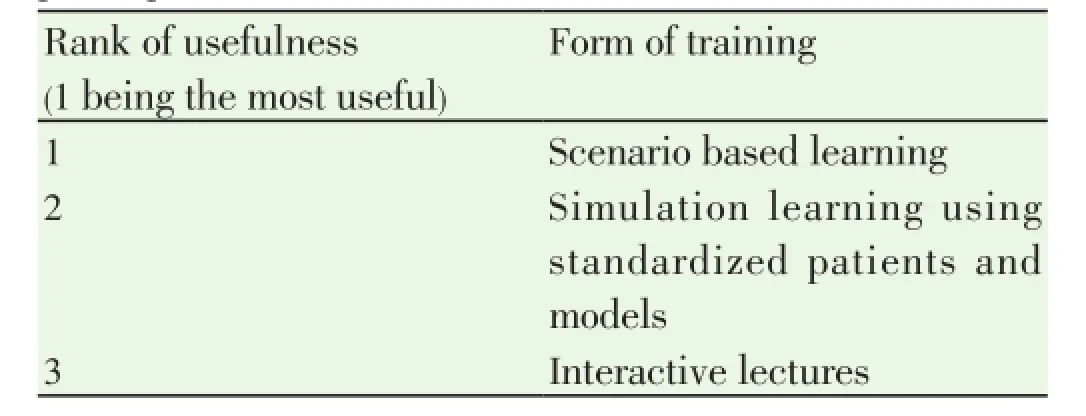

Analysis of question 8 of the pre-LLF-model questionnaire demonstrated that out of the 6 listed forms of training methods; scenario-based learning was the most desired, followed by simulation learning and then interactive lectures (Table 8).

Table 8. Forms of training in order of usefulness (An average of all participants).

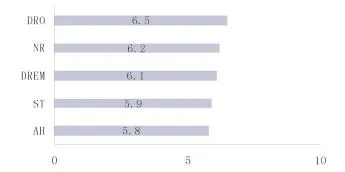

Analysis of question 10 of the pre-LLF-model questionnaire revealed that participants in the DRO group were most satisfied with their current communication capabilities, this is followed by NR, DREM, ST and finally AH.

Figure 7. Average satisfaction score according to profession (10 points being the most satisfied).

Analysis of question 11 of the pre-LLF-model questionnaire showed that participants in the DREM group have been involved in the most number of complaints, followed by AH, NR, DRO and lastly, ST.

Figure 8. Percentage of participants in each profession that have been involved in complaints (%).

4. Discussion

Our results show positive feedback for the “Look, Listen and Feel” (LLF) model by participants from varied areas of healthcare. A large majority of participants found the LLF model useful as the acronym was applicable to all kinds of situations and made recalling the important aspects of communication simple. Two weeks is a relatively long amount of time whereby a newly taught concept can be readily forgotten once the participants leave the presentation room and bustle about their daily duties. However at the end of the two weeks, the LLF model was still fresh in their minds and participants continued to apply the LLF model in their work. This is evident from their responses in the post-LLF-model questionnaire. Participants also felt that the LLF model could be easily shared. Hence the simplicity of the model plants another channel for good communication to be advanced amongst healthcare workers. Responses were also derived from a broad spectrum of healthcare workers ranging from doctors, nurses, allied healthcare workers and medical students. This demonstrates an all round acceptance of the LLF model amongst healthcare workers. In light of this, the LLF model is proven not to be limited to one aspect of communication, for example solely between doctors and patients, but can be useful in all kinds of communication relationships.

Other available communication-training tools include the “5 C’s of consultation”[12], the “SBAR” tool[13] and the“PIQUED”framework.14 These tools are designed mainly to aid inter-physician consultation and are effective in providing a structure for wording a message to another healthcare worker. However the LLF model is targeted towards shaping a right attitude in healthcare workers. Having the right attitude can greatly influence how we think and thus how we communicate[2]. A quote from Winston Churchchill aptly asserts that “Attitude is a little thing that makes a big difference”.

The LLF model stands out in comparison to other modes of communication training as it provides a flexible framework, building on a phrase that is already ingrained in most healthcare workers. Teaching tools like the Calgary-Cambridge Referenced Observation Guide[15] provide a wealth of information on effective communication. However long manuals like this may only benefit a small amount of learners who can afford the time to digest its components.

The LLF model is able to trigger conscious reflection on one’s communication efficiency without requiring healthcare workers to memorize a new phrase to add on to their everexpanding list of acronyms and mnemonics.

Results for our secondary aim bolster the need for communication training. In the open-ended response, participants mainly cited the 5 C’s of consultation as their prior communication-training tool. Despite a high percentage of participants having already undergone previous communication training, the percentage of those wanting to attend another course remained high. This reflects that participants still feel incompetent in their communication skills and desire to improve their skills. Many of them are involved with many (at least 5) aspects of communication at work. The LLF is a tool that allows them to apply the right attitude towards all situations and people from different lines of work.

Participants also highlighted that they found most difficulty in communicating with upset and angry relatives, informing death and dealing with language barriers. In all these situations, non-verbal communication may prove to be more effective than verbal communication. Based on feedback from our participants, many are unaware of the importance of non-communication. The LLF model emphasizes the importance of ‘Feel’ whereby empathy is offered to upset patients and their relatives when they may not be in a right state of mind to receive healing from scripted speech.

Our study has shown that communication training is vital in healthcare today, especially in busy departments like emergency medicine. The “Look, Listen and Feel”(LLF) model is proposed to aid communication training by targeting the attitudes of healthcare workers.

Future plans for the “Look, Listen and Feel”(LLF) model involve further exploration of its usefulness, evolving and improving the LLF concept, and constantly evaluating feedback from users. The LLF model can be advanced beyond the emergency department and tested in other specialties and vocations. Larger scale studies with more participants are important to further substantiate the usefulness of the LLF model. Randomized controlled trials can also be conducted to objectively test the efficacy of this communication intervention. Prioritizing doctors as our main audience for learning the LLF model may improve healthcare communication significantly, as patients determine the doctor-patient relationship to be one of the most important factors in their healing process. The LLF model will need to be constantly revised and updated with examples that can better relate to users, while maintaining the core foundations of communication: to Look at, to Listen to and to Feel for people we interact with. The feedback received for preference in teaching style can be applied to how the concept of LLF is conveyed to new audiences. Evaluation of the LLF model is the key to determining its relevance and this can be done through remodeling our questionnaires so as to elicit deeper feedback from users. Surveys can also be extended to include patient feedback, as patients are ultimately the end-point users of the healthcare system.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

[1] Taylor DM, Wolfe R, Cameron PA. Complaints from emergency department patients largely result from treatment and communication problems. Emergen Med Australasia 2002; 14(1): 43-49.

[2] Lateef F. “Look, Listen and Feel” a new twist in our communication process. South East Asian J Med Education 2008; 2(2).

[3] Lateef F. “Look, Listen and Feel” a new twist in our communication process.[Online]. Available from http://seajme. md.chula.ac.th/articleVol2No2/CM1_Fatimah%20Lateef.pdf. [Accesed on 2008].

[4] Coiera EW, Jayasuriya RA, Hardy J, Bannan A, Thorpe MEC. Communication loads on clinical staff in the emergency department. Med J Australia 2002; 176(9): 415-418.

[5] Perednia DA, Allen A. Telemedicine technology and clinical applications. JAMA 1995; 273(6): 483-488. doi:10.1001/ jama.1995.03520300057037.

[6] Wallace S, Wyatt J, Taylor P. Telemedicine in the NHS for the millennium and beyond. BMJ 1998; 74: 721-728.

[7] Beckjord EB, Rutton LJF, Squiers L, Arora NK, Volckmann L, Moser RP, et al. Use of the internet to communicate with health care providers in the United States: Estimates from the 2003 and 2005 health information national trends surveys (HINTS). J Med Internet Res 2007; 9(3): e20.

[8] Crane JA. Patient comprehension of doctor-patient communication on discharge from the emergency department. J Emerg Med 1997; 15(1): 1-7.

[9] Jagosh J1, Donald Boudreau J, Steinert Y, Macdonald ME, Ingram L. The importance of physician listening from the patients’perspective: enhancing diagnosis, healing, and the doctor-patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns 2011; 85(3): 369-374. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.028.

[10] Conscious Competence Learning Model.[Online]. Available from: http://www.businessballs.com/consciouscompetencelearningmodel .htm [Accessed on Feb 27, 2014].

[11] Crosbie R. Learning the soft skills of leadership. Ind Commerc Train 2005; 37(1): 45-51.

[12] American Heart Association. BLS for healthcare providers: Students Manual. Dallas: American Heart Association; 2005

[13] Kessler CS, Afshar Y, Sardar G, Yudkowsky R, Ankel F, Schwartz A. A prospective, randomized, controlled study demonstrating a novel, effective model of transfer of care between physicians: the 5 Cs of consultation. Acad Emerg Med 2012; 19(8): 968-974. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01412.x.

[14] Haig KM, Sutton S, Whittington J. SBAR: A shared mental model for improving communication between clinicians. Joint Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2006; 32(3):167-175.

[15] Chan T, Orlich D, Kulasegaram K, Sherbino J. Understanding communication between emergency and consulting physicians: a qualitative study that describes and defines the essential elements of the emergency department consultation-referral process for the junior learner. CJEM 2013; 15(1): 42-51.

[16] Kurtz SM, Silverman JD. The Calgary-Cambridge Referenced Observation Guides: an aid to defining the curriculum and organizing the teaching in communication training programmes. Med Educ 1996; 30: 83-89.

ment heading

10.1016/S2221-6189(14)60061-5

*Corresponding author: Fatimah Lateef, Assoc Prof. Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore general Hospital, Outram Road, Singapore 169608.

Tel: 65 63213558

Fax: 65 63214873

E-mail: Fatimah.abd.lateef@sgh.com.sg

Journal of Acute Disease2014年4期

Journal of Acute Disease2014年4期

- Journal of Acute Disease的其它文章

- Acute and sub-acute toxicity study of Clerodendrum inerme, Jasminum mesnyi Hance and Callistemon citrinus

- Time-critical AMI Detection: A novel and fast technique using the 12-lead ECG

- Epidemiological survey on scorpionism in Gotvand County, Southwestern Iran: an analysis of 1 067 patients

- The acute effect of the antioxidant drug “U-74389G” on red blood cells levels during hypoxia reoxygenation injury in rats

- Successful treatment of lower urinary tract obstruction with peritonealamniotic and vesicoamniotic shunting

- Simvastatin-induced Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis