Sleep quality improved follow ing a single session of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise in older women:Results from a pilot study

Xuewen Wng,Shwn D.Youngstedt

aDepartment of Exercise Science,University of South Carolina,Columbia,SC 29208,USA

bDivision of Geriatrics and Nutritional Science,Washington University School of Medicine,St.Louis,Missouri 63110,USA

Sleep quality improved follow ing a single session of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise in older women:Results from a pilot study

Xuewen Wanga,b,*,Shawn D.Youngstedta

aDepartment of Exercise Science,University of South Carolina,Columbia,SC 29208,USA

bDivision of Geriatrics and Nutritional Science,Washington University School of Medicine,St.Louis,Missouri 63110,USA

Background:Poor sleep quality is associated w ith adverse effects on health outcomes.It is notclear whether exercise can improve sleep quality and whether intensity of exercise affects any of the effects.

Methods:Fifteen healthy,non-obese(body mass index=24.4±2.1 kg/m2,mean±SD),sedentary(<20 m in of exercise on no more than 3 times/week)older women(66.1±3.9 years)volunteered for the study.Peak oxygen consumption(VO2peak)was evaluated using a graded exercise teston a treadm illw ith a metabolic cart.Follow ing a 7-day baseline period,each participantcompleted two exercise sessions(separated by 1 week)w ith equal caloric expenditure,but at different intensities(60%and 45%VO2peak,sequence random ized)between 9:00 and 11:00 am.A w rist ActiGraph monitor was used to assess sleep at baseline and two nights follow ing each exercise session.

Results:The average duration of the exercise was 54 and 72 m in,respectively at 60%(moderate-intensity)and 45%VO2peak(light-intensity). Wake time after sleep onsetwas significantly shorter(p=0.016),the numberofawakenings was less(p=0.046),and totalactivity counts were lower(p=0.05)after the moderate-intensity exercise compared to baseline no-exercise condition.

Conclusion:Our data showed that a single moderate-intensity aerobic exercise session improved sleep quality in older women.

CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.A ll rights reserved.

Actigraphy;Activity counts;Exercise;Older adults;Sleep quality;Wake after sleep onset

1.Introduction

Poor sleep quality is associated w ith adverse effects on health outcomes.1,2A large proportion of older adults tend to have poor,fragmented sleep quality such as waking up frequently.3The 2003 National Sleep Foundation survey showed thatone third ofadults aged 64 years and olderhave at least one sleep-related complaint such as difficulty falling asleep,being awake a lot during the night and waking up too early.4

Exercise is often considered a non-pharmacological approach that could have beneficial effects on sleep.This is supported by epidem iologic studies show ing an association between self-reported exercise and better sleep.5,6Additionally,some evidence indicates that aerobically fi t individuals have shorter sleep-onset latencies,less wake time after sleep onset,and higher sleep efficiency than their sedentary peers,7and increased fi tness has been associated w ith improvements in subjectively-assessed sleep.8However,results from experimentalexercise studies have been m ixed.Severalstudies have shown a positive impact on self-reported sleep among older normal sleepers follow ing exercise training protocols, including 30-m in 67%—70%or 30%—40%heart rate reserve of cycling for 3 times/week,9daily 30-m in walking,calisthenics,or dancing,10and 60-m in Tai Chi practice tw ice a week.11Positive effects of exercise on sleep have also beenfound in studies of seniors who had m ild to moderate sleep problems.12—16

Fewer studies of older adults have assessed sleep objectively via polysomnography or actigraphy.Among these studies,beneficialeffects ofexercise have been shown in older adults following 60%—85%peak heart rate 5 days/week 35—40 min each session,17and 60-m in moderate-intensity running 3 days/week;18,19however,daily 30 m in of m ild to moderate physical activity10or one afternoon session of 40—42 min of exhaustive aerobic exercise did not influence sleep.7Thus,studies in older adults have presented inconsistent results regarding the effects of exercise on sleep,which may be related to variations in exercise intensity,volume,and time between exercise and sleep,20,21as well as whether sleep was assessed subjectively or objectively.

A few studies in young adults have exam ined whether the intensity of a bout of exercise alters its effects on sleep:one study found no differences in sleep latency or number of awakenings between exercise bouts at 70%for 30 m in and 40%peak oxygen consumption(VO2peak)w ith the same exercise dose;22another study showed that sleep onset latency, wake after sleep onset,rapid eye movementsleep onset,sleep efficiency and slow-wave sleep after treadm ill running at45%, 55%,65%,and 75%for 40 m in were not different from those after no-exercise control.23Due to age-related physiological changes,24exercise may have different effects in older adults from young adults.However,no study has been designed to determ ine whether the intensity of exercise influences any effect on sleep in older adults.Thus,the purpose of this study was to determ ine whether light-and moderate-intensity acute exercise sessions thatmeetpublic health recommendations for older adults(moderate-intensity activities,accumulate at least 30 or 60 m in/day to total 150—300 m in/week),25,26improve objectively measured sleep quality in a group of healthy women 61—74 years of age using a crossover design.

2.M ethods

2.1.Subjects and screening evaluations

This study was an ancillary to a study designed to examine the effects of exercise intensity on non-exercise activity thermogenesis in older women(ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00988299).Fifteen healthy,non-obese,older women volunteered for this study(Table 1).This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Washington University School of Medicine in St.Louis,MO,USA,and w ritten informed consent was obtained from all subjects beforeparticipation in the study.None of the subjects smoked and all were weight stable(±1 kg)and sedentary(<20 m in of exercise no more than 3 times/week)for at least 3 months before entering the study.

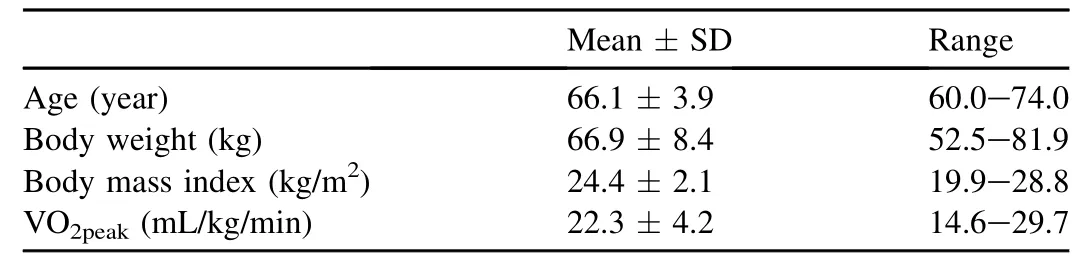

Table 1 Subject characteristics.

All subjects completed a comprehensive medical exam ination,including a detailed self-reported history,physical examination,a resting electrocardiogram,standard blood tests, and an oralglucose tolerance testperformed by physicians and nurses in Washington University Clinical Research Unit. Blood tests included:complete metabolic panel,complete blood count,and thyroid stimulating hormone.Standard cutoffs that are used in the hospital and associated clinics for normal values were used to include or exclude subjects.For example,the normal ranges for the follow ing blood variables are:white blood cell count,4.5—13.5 K/μL;red blood cell count,3.90—5.30 M/μL;hemoglobin,11.5—16.0 g/dL;thyroid stimulating hormone(TSH),0.46—4.70μIU/m L;blood urea nitrogen (BUN), 5—25 MG/dL; blood creatinine, 0.50—1.00 MG/dL;aspartate transam inase(AST),8—39 U/L; and alanine am inotransferase(ALT),9—52 U/L.Subjects w ith diabetes,impaired fasting glucose,or impaired glucose tolerance based on American Diabetes Association criteria27were excluded from the study.None of the subjects had evidence of illness,self-reported insomnia,or were taking medications known to affect sleep or to assist sleep.Their daily caffeine intake was less than 500 mg.

2.2.Study protocol

VO2peakwas evaluated during a graded exercise test on a treadm ill.Heart rhythm and rate were continuously monitored (Marquette MAX-1;ParvoMedics,Sandy,UT,USA)and expired air was analyzed by using a metabolic cart(TrueOne 2400;ParvoMedics).Subjects walked ata constant speed and the inclination of the treadm ill was increased by 3%every 2 m in until volitional exhaustion and/or two of the follow ing criteria were achieved:respiratory exchange ratio≥1.15;heart rate greater than the age-predicted maximum (220-age (year));or plateau in VO2.

Each subject performed two treadm ill walking sessions between 9:00 and 11:00 am follow ing an overnight fast.One walking session was at light intensity(45%VO2peak)and one at moderate intensity (60% VO2peak)w ith randomized sequence,separated by at least 1 week.A snack bar (NatureValley,250 kcal)was provided before the exercise sessions.The two exercise sessions were performed on same day of the week for each individual to reduce the influence of variation in daily schedule on outcomes.No travelacross time zone occurred during the 2 weeks prior to the exercise sessions.During the exercise,expired air was analyzed periodically by using a metabolic cart(TrueOne 2400)to ensure the appropriate exercise intensity was achieved.The duration of exercise was variable and ended when subjects have spent 3.5 kcal(14.7 kJ)energy per kg body weight,based on the volume of the oxygen consumed.We chose an equal exercise energy expenditure relative to body weight for all subjects rather than a fixed time period to reduce the influence of bodyweightdifferences on energy expended between subjects.This also allows us to determ ine the effects of exercise intensity w ithout the influence of differential energy expended during exercise.

Subjects wore a w rist ActiGraph monitor(GT3X+;Acti-Graph,Pensacola,FL,USA)24 h each day for 7 days at baseline,and 48 h after each exercise session.There were no instructions regarding sleep,physical activity,or dietary intake.The output from the monitors was analyzed using the manufacturer provided software ActiLife 6.5.The Cole—K-ripke algorithm28was used to determ ine minute-by-m inute asleep/awake status.Sleep onset was the fi rst m inute that the algorithm scored“asleep”.Total sleep time was the total number of m inutes scored as“asleep”.Wake after sleep onset was the total number of m inutes a subject was awake after sleep onsetoccurred.Awakening was the number of different awakening episodes as scored by the algorithm.Sleep efficiency referred to the number of m inutes asleep divided by the totalnumber of m inutes from sleep onset to sleep end(sum of asleep and awakenings after sleep onset).

2.3.Statistical analysis

Data are reported as means±SD.Analyses of variance w ith repeated measures were used to compare sleep parameters at baseline(no exercise)to after light-and moderateintensity exercise sessions.Pairedttests for each pairs of conditions were performed where a significant(or tend-to-be significant)w ithin-subject difference among the three conditions were found.Ap≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant,and 0.05<p<0.10 was considered tend-to-be significant.

3.Results

Subjects in this study were non-obese older women(Table 1).The average duration of exercise was 72± 15 and 54±11 m in,respectively,for the light-(45%VO2peak)and moderate-intensity(60%VO2peak)exercise session.

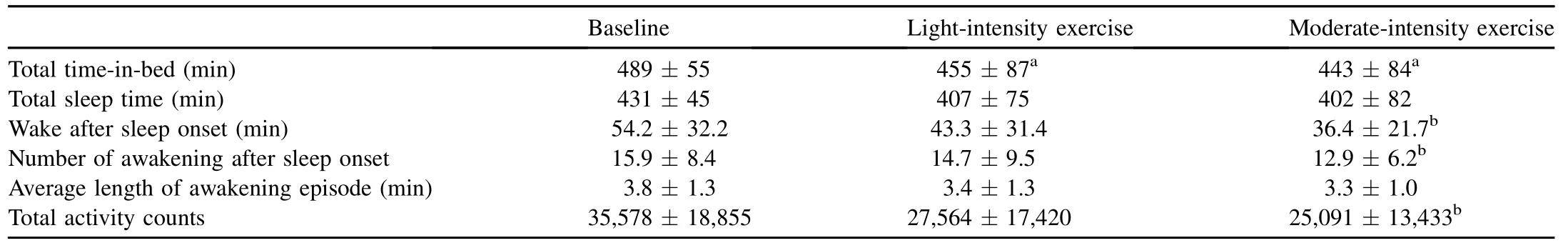

Table 2 displays sleep parameters at baseline w ithout exercise and after light-and moderate-intensity exercise.Total timein-bed tended to be different among the three conditions (p=0.077).Specifically,it tended to be~30 and 40 m in, respectively,less after light-and moderate-intensity exercises (p=0.098 and 0.063,respectively),compared to w ithout exercise.There were significant differences in wake time after sleep onset among the three conditions(p=0.031).A fter the moderate-intensity exercise,itwas~15 m in shorter compared to baseline(p=0.016).There was also a trend for significant differences in the number of awakening episodes(p=0.092), and it was less after the moderate-intensity exercise than at baseline(p=0.046).Likew ise,there was a trend forsignificant differences in total activity counts(pfor trend=0.071),and after the moderate-intensity exercise they were ~9400 (~21%)lower than at baseline(p=0.05)(Table 2).There were no differencesin sleep time(p=0.237)oraverage length of awakening episode(p=0.362)among the three conditions.

We also exam ined these variables in the fi rst and second night after the exercise sessions separately.Results showed sim ilar trends.We thought that the average of the two nights would better represent the exercise effectbecause sleep can be affected by many factors;therefore,we only presented the average values here.

4.Discussion

The most interesting findings of this study were that after the moderate-intensity aerobic exercise,wake time after sleep onset,number of awakenings,and total activity counts were significantly lower than those parameters when no exercise was performed.After the light-intensity aerobic exercise,the values of these parameters were between those after the moderate-intensity exercise and w ithout exercise,although they were not statistically different from either.This study showed that the moderate-intensity exercise improved sleep quality,and suggested thatperform ing exercise and increasing the intensity of exercise may influence sleep quality positively in older adults.

The reduction in wake time after sleep onsetand number of awakenings follow ing exercise may be partly explained by the reductions in the amountof time spentin bed.Nonetheless,the %of time awake after sleep onset was less follow ing light (9%)and moderate exercise(8%)than baseline no-exercise (11%).More importantly,total activity counts were lower (13%and 21%after light-and moderate-intensity exercise, respectively)compared to w ithout exercise.These findings perhaps suggest better sleep quality especially after the moderate-intensity exercise.

A few previous studies have exam ined whether intensity and duration of exercise influences the effects of single boutsof exercise on sleep quality assessed by objective methods in young adults.These studies either did not show exercise impacted sleep compared to no-exercise control,23,29or found no difference among exercise at various intensities or durations on sleep.22,29,30In one study,30-m in running sessions at45%,60%,and 75%of VO2maxdid not result in any difference in sleep quality measured by actigraphic monitors.30In another study,no difference in sleep latency or number of awakenings was found between exercise bouts at 70%VO2peakfor 30 m in and 40%VO2peakw ith the same exercise volume.22Likew ise,sleep latency,wake after sleep onset,rapid eye movement sleep onset,sleep effi ciency and slow-wave sleep after treadm ill running at 45%,55%,65%, and 75%for 40 m in were not different from these variables assessed after a no-exercise control treatment.23Another study showed that1 h of cycling exercise at60%VO2peakdid not result in any difference in awakening or sleep efficiency, compared to low-intensity exercise and no exercise control condition.29

Table 2 Sleep parameters during 7-day baseline and 48 h after light-and moderate-intensity exercise sessions.

In the presentstudy,we found significanteffects follow ing moderate-intensity exercise compared to w ithout exercise, although light-intensity exercise did not result in statistically different effects.In comparison to the above-mentioned studies,our participants were older;the duration of the moderate-intensity exercise was longer than those exercise bouts at similar intensities;23,29,30and the volume of exercise in our study was greater than at least three22,29,30of the four studies.Thus,both the intensity and volume of exercise may influence its effects on sleep quality.The necessary exercise intensity and volume to make an impact on sleep quality may also be lower in older than in young adults.

In older adults,a study by Edinger etal.7did not find sleep measured by polysomnography was any better after bicycle exercise at incremental 6-m in workloads to exhaustive fatigue of 40—42 m in.Compared to their study,the moderateintensity exercise in our study was longer.Most previous studies in older adults exam ined the effects of a period of exercise training on sleep quality.Although we cannotdirectly compare our results w ith these exercise training studies, findings from these studies appear to support that the intensity and volume of exercise influence its effects on sleep quality. For example,in the study by Benloucif etal.,10sleep quality was assessed in healthy olderadults before and after a 2-week intervention which included a total of 60 m in of m ild to moderate physical activity.They found that sleep quality did not improve assessed by actigraphy or polysomnography.In contrast,exercise at longer duration and intensity(60 m in/day atan intensity equal to the ventilatory threshold)for24 weeks decreased awake time during sleep in healthy older adults.18,19Additionally,older adults w ith sleep problems or adults w ith even older age than ours appear to benefi t from exercise training by getting improved sleep quality and efficiency (objectively measured)even at lower intensity and shorter duration.17,31—33Thus,the health status and age also play a role in the effects of exercise on sleep quality.

The mechanisms by which exercise improves sleep quality are likely multi-factorial.Ithas been suggested that the effects of exercise on sleep are related to antidepressant effects, anxiety reduction,and changes in serotonin levels.20,34

The strength of this study was that it was designed to compare exercise bouts at two different intensities butw ith the same volume.The energy intake in the morning was equal before both exercise bouts.This design was unique especially w ith regard to the energy conservation theory of sleep because we were able to tease out the effect of energy expenditure of exerciseper seon sleep.Also,sleep was monitored in the home environment,and less susceptible to confounding of laboratory recording.

Although using actigraphy to estimate sleep is not as accurate as polysomnography,it has a number of advantages, including that it offers a convenient method for estimating sleep on multiple nights w ith lim ited burden to subjects,w ith acceptable reliability.35,36Also,our participants did notuse a diary to record the time they went to bed.Thus,we could only rely on the actigraphic recording to determ ine their time-inbed,and was not able to accurately determ ine the time getting into bed.As a result,we decided not to report sleep latency(time from getting into bed to the point of falling asleep),but rather focus on wake time after sleep onset and activity counts during time-in-bed.Participants also did not record daytime napping.However,there did not appear to be markedly differentperiods of lack ofactivity of the actigraphic recording,in the afternoons on exercise days in comparison to baseline w ithout exercise.In addition,the sample size of our study was small and inter-subject variance was large;nonetheless,our findings suggest an effect of exercise on sleep which warrants further investigation.

5.Conclusion

In this study,wake time after sleep onset,number of awakenings,and total activity counts were significantly reduced after a session of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise compared to those w ithout exercise.Thus,we have demonstrated that an approximately 1-h single session of moderateintensity brisk walking improves sleep quality in older women.

Acknow ledgments

The authors thank Rachel Burrows and Hadia Jeffery for study coordination,the staff of the Clinical Research Unit for their help in perform ing the study,and the study subjects for their participation.This publication was made possible by US National Institutes of Health Grants(K99AG031297 and RR024992)(Washington University School of Medicine Clinical Translational Science Award).

1.Hoevenaar-Blom MP,Spijkerman AM,Kromhout D,van den Berg JF, Verschuren WM.Sleep duration and sleep quality in relation to 12-year cardiovascular disease incidence: the MORGEN study.Sleep2011;34:1487—92.

2.Hung HC,Yang YC,Ou HY,Wu JS,Lu FH,Chang CJ.The relationship between impaired fasting glucose and self-reported sleep quality in a Chinese population.Clin Endocrinol(Oxf)2013;78:518—24.

3.Dement WC,M iles LE,Carskadon MA.“White paper”on sleep and aging.J Am Geriatr Soc1982;30:25—50.

4.Foley D,Ancoli-Israel S,Britz P,Walsh J.Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults:results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey.J Psychosom Res2004;56:497—502.

5.Sherrill DL,Kotchou K,Quan SF.Association of physical activity and human sleep disorders.Arch Intern Med1998;158:1894—8.

6.Kim K,Uchiyama M,Okawa M,Liu X,Ogihara R.An epidem iological study of insomnia among the Japanese general population.Sleep2000;23:41—7.

7.Edinger JD,Morey MC,Sullivan RJ,Higginbotham MB,Marsh GR, Dailey DS,et al.Aerobic fi tness,acute exercise and sleep in older men.Sleep1993;16:351—9.

8.Tworoger SS,Yasui Y,Vitiello MV,Schwartz RS,Ulrich CM,Aiello EJ, et al.Effects of a yearlong moderate-intensity exercise and a stretching intervention on sleep quality in postmenopausal women.Sleep2003;26:830—6.

9.Stevenson JS,Topp R.Effects of moderate and low intensity long-term exercise by older adults.Res Nurs Health1990;13:209—18.

10.Benloucif S,Orbeta L,Ortiz R,Janssen I,Finkel SI,Bleiberg J,et al. Morning or evening activity improves neuropsychological performance and subjective sleep quality in older adults.Sleep2004;27:1542—51.

11.Nguyen MH,Kruse A.A random ized controlled trial of Tai chi for balance,sleep quality and cognitive performance in elderly Vietnamese.Clin Interv Aging2012;7:185—90.

12.King AC,OMan RF,Brassington GS,Bliw ise DL,Haskell WL.Moderate-intensity exercise and self-rated quality of sleep in older adults:a random ized controlled trial.JAMA1997;277:32—7.

13.Singh NA,Clements KM,Fiatarone MA.A random ized controlled trialof the effect of exercise on sleep.Sleep1997;20:95—101.

14.Singh NA,Stavrinos TM,Scarbek Y,Galambos G,Liber C,Fiatarone Singh MA.A random ized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adults.J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2005;60:768—76.

15.Reid KJ,Baron KG,Lu B,Naylor E,Wolfe L,Zee PC.Aerobic exercise improves self-reported sleep and quality of life in older adults w ith insomnia.Sleep Med2010;11:934—40.

16.Irw in MR,Olmstead R,Motivala SJ.Improving sleep quality in older adults w ith moderate sleep complaints:a random ized controlled trial of Tai Chi Chih.Sleep2008;31:1001—8.

17.King AC,Pruitt LA,Woo S,Castro CM,Ahn DK,Vitiello MV,et al. Effects of moderate-intensity exercise on polysomnographic and subjective sleep quality in olderadults w ith mild to moderate sleep complaints.J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2008;63:997—1004.

18.Lira FS,Pimentel GD,Santos RV,Oyama LM,Damaso AR,Oller do Nascimento CM,et al.Exercise training improves sleep pattern and metabolic profi le in elderly people in a time-dependent manner.Lipids Health Dis2011;10:1—6.

19.Santos RVT,Viana VAR,Boscolo RA,Marques VG,Santana MG, Lira FS,et al.Moderate exercise training modulates cytokine profi le and sleep in elderly people.Cytokine2012;60:731—5.

20.Youngstedt SD,O’Connor PJ,Dishman RK.The effects of acute exercise on sleep:a quantitative synthesis.Sleep1997;20:203—14.

21.Yoshida H,Ishikawa T,Shiraishi F,Kobayashi T.Effects of the tim ing of exercise on the night sleep.Psychiatry Clin Neurosci1998;52:139—40.

22.Jones H,George K,Edwards B,Atkinson G.Exercise intensity and blood pressure during sleep.Int J Sports Med2009;30:94—9.

23.Wong SN,Halaki M,Chow CM.The effects of moderate to vigorous aerobic exercise on the sleep need of sedentary young adults.J Sports Sci2013;31:381—6.

24.Boss GR,Seegmiller JE.Age-related physiological changes and their clinical significance.West J Med1981;135:434—40.

25.Nelson ME,RejeskiWJ,Blair SN,Duncan PW,Judge JO,King AC,etal. Physical activity and public health in older adults:recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association.Med Sci Sports Exerc2007;39:1435—45.

26.Chodzko-Zajko WJ,Proctor DN,Fiatarone Singh MA,M inson CT, Nigg CR,Salem GJ,etal.American College of Sports Medicine position stand.Exercise and physical activity for older adults.Med Sci Sports Exerc2009;41:1510—30.

27.American Diabetes Association.Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus.Diabetes Care2005;28:S37—42.

28.Cole RJ,Kripke DF,Gruen W,Mullaney DJ,Gillin JC.Automatic sleep/ wake identification from w rist activity.Sleep1992;15:461—9.

29.O’Connor PJ,Breus M J,Youngstedt SD.Exercise-induced increase in core temperature does not disrupta behavioralmeasure of sleep.Physiol Behav1998;64:213—7.

30.Myllymaki T,Rusko H,Syvaoja H,Juuti T,Kinnunen ML,Kyrolainen H. Effects of exercise intensity and duration on nocturnal heart rate variability and sleep quality.Eur J Appl Physiol2012;112:801—9.

31.Richards KC,Lambert C,Beck CK,Bliw ise DL,Evans WJ,Kalra GK, et al.Strength training,walking,and social activity improve sleep in nursing home and assisted living residents:random ized controlled trial.J Am Geriatr Soc2011;59:214—23.

32.Tanaka H,Taira K,Arakawa M,Urasaki C,Yamamoto Y,Okuma H,etal. Short naps and exercise improve sleep quality and mental health in the elderly.Psychiatry Clin Neurosci2002;56:233—4.

33.Naylor E,Penev PD,Orbeta L,Janssen I,Ortiz R,Colecchia EF,et al. Daily social and physical activity increases slow-wave sleep and daytime neuropsychological performance in the elderly.Sleep2000;23:87—95.

34.Youngstedt SD.Effects of exercise on sleep.ClinSports Med2005;24:355—65.

35.Ancoli-Israel S,Cole R,A lessi C,Chambers M,Moorcroft W,Pollak CP. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms.Sleep2003;26:342—92.

36.Jean-Louis G,Kripke DF,Mason WJ,Elliott JA,Youngstedt SD.Sleep estimation from w rist movement quantified by different actigraphic modalities.J Neurosci Methods2001;105:185—91.

Received 24 July 2013;revised 27 September 2013;accepted 1 November 2013 Available online 10 January 2014

*Corresponding author.Departmentof Exercise Science,University of South Carolina,Columbia,SC 29208,USA.

E-mail address:xwang@sc.edu(X.Wang)

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

2095-2546/$-see front matter CopyrightⒸ2014,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.A ll rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2013.11.004

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年4期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2014年4期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer:Loading mechanisms, risk factors,and prevention programs

- Sports medician and science in soccer

- The effect of active sitting on trunk motion

- Using Sensewear armband and diet journal to promote adolescents’energy balance know ledge and motivation

- Parental perceptions of the effects of exercise on behavior in children and adolescents w ith ADHD

- Effect of turf on the cutting movement of female football players