A single subcutaneous dose of tramadol for mild to moderate musculoskeletal trauma in the emergency department

Alejandro Cardozo, Carlos Silva, Luis Dominguez, Beatriz Botero, Paulo Zambrano, Jose Bareño

1Emergency Department, Clinica Las Vegas, Medellin, Colombia

2Epidemiology Department, Universidad CES, Medellin, Colombia

Corresponding Author:Alejandro Cardozo, Email: Galeno026@gmail.com

A single subcutaneous dose of tramadol for mild to moderate musculoskeletal trauma in the emergency department

Alejandro Cardozo1, Carlos Silva1, Luis Dominguez1, Beatriz Botero1, Paulo Zambrano1, Jose Bareño2

1Emergency Department, Clinica Las Vegas, Medellin, Colombia

2Epidemiology Department, Universidad CES, Medellin, Colombia

Corresponding Author:Alejandro Cardozo, Email: Galeno026@gmail.com

BACKGROUND:Mild to moderate musculoskeletal trauma is a common cause for an emergency room visit, and frequent pain is one of the cardinal symptoms of consultation. The objective of this study is to assess the perception of a single subcutaneous dose of 50 mg tramadol for pain management in patients with mild to moderate musculoskeletal trauma, likewise to appraise the perception of pain by subcutaneous injection.

METHODS:A total of 77 patients, who met inclusion criteria, received a single subcutaneous dose of tramadol. Pain control was evaluated based on the verbal numerical pain scale (0–10) at baseline, 20 and 60 minutes; similarly, pain perception was evaluated secondary to subcutaneous injection of the analgesic.

RESULTS:On admission, the average pain perceived by patients was 8; twenty minutes later, 89% of the patients reported fi ve or less, and after sixty minutes, 94% had three or less on the verbal numerical pain scale. Of the patients, 88% reported pain perception by verbal numeric scale of 3 or less by injection of the drug, and 6.5% required a second analgesic for pain control. Two events with drug administration (soft tissue infection and mild abdominal rectus injection) were reported.

CONCLUSION:We conclude that a single subcutaneous dose of tramadol is a safe and effective option for the management of patients with mild to moderate pain and musculoskeletal disease in the emergency department.

Tramadol; Analgesic routes; Subcutaneous; Acute pain; Emergency department

INTRODUCTION

Acute pain is one of the leading causes of visits to the emergency department (ED),[1–4]including a large percentage that is secondary to mild to moderate musculoskeletal trauma,[5]representing an important ED overcrowding and extended service times associated with poor control of disabling pain.[6–8]

The analgesic routes in health services are de fi ned as enteral and parenteral; within the latter, the subcutaneous (SC) route has been insufficiently studied in urgent patients.

Hence, we seek to know if SC tramadol is perceived as effective by patients with mild to moderate musculoskeletal trauma admitted in a de fi ned period in our ED.

The study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of SC tramadol in patients with mild to moderate musculoskeletal trauma based on the verbal numerical pain scale at twenty and sixty minutes, so as to assess whether the pain perceived by SC injection supports its administration in relation to the pain perceived by the trauma.

METHODS

Clinica Las Vegas in Medellin, Colombia, is a tertiary care complexity center with 51 000 visits per year. Approximately, 20% of visits correspond to mild to moderate musculoskeletal trauma due to workplace, traffic-related, domestic, or sports accidents. In September and October, 2013, 77 patients who met inclusion criteria were attended. The patients included those with mild to moderate musculoskeletal trauma aged over 18 years. They were ED walk-in patients who did not require stitches and had no exclusion criteria: patients who were previously medicated with analgesics before consulting the ED or that had been consuming painkillers for some pathology, epilepsy, liver disease, tramadol allergy, trauma requiring hospitalization or intravenous medication according to the opinion of treating physician, or pregnancy.

This study was approved by the ethical committee of the clinic prior to verbal patient consent and veri fi cation of tramadol blister for subcutaneous delivery authorized by the Instituto Nacional de Vigilancia de Medicamentos (INVIMA). A single subcutaneous dose (50 mg) was supplied. The injection was provided by nursing assistant using hypodermic syringe of insulin in the periumbilical area following the same technique of insulin delivery. For each patient, a record consisting of a checklist of inclusion and exclusion criteria and boxes to record the number given by the patient in the verbal pain scale (0 no pain; 10 severe pain) to the injury perceived by the trauma at 20 and 60 minutes after the administration of tramadol. The same pain scale was used to record the value perceived by subcutaneous injection. Likewise, the need for rescue medication was assessed.

Study type

An observational prospective registry, or the questionnaire to pain scales (initial trauma pain and subcutaneous pain) was designed by a blinded doctor on the collection of data. Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS version 18, and Friedman's test was used to compare pairwise results.

RESULTS

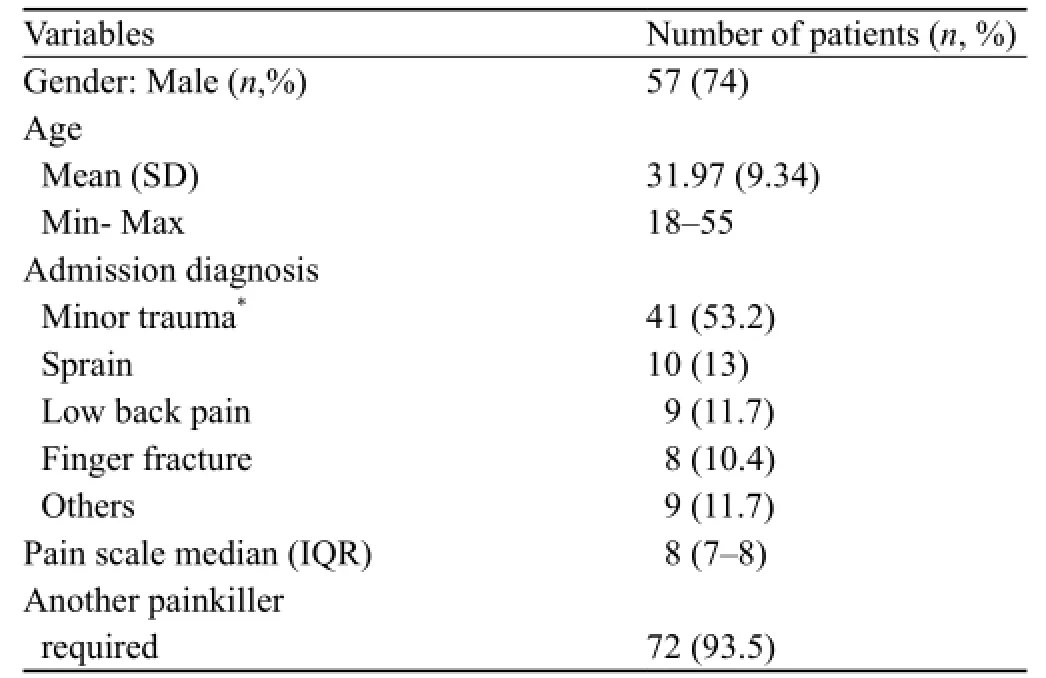

In September and October, 2013, 77 patients were included in the registry. In this series, 74% were men (Table 1). Their mean age of the patients was 31 years (18–55). 53% of the patients were diagnosed with minormusculoskeletal trauma, 13% with sprain, 11% with acute low back pain, and 10% with closed fractured fi ngertips.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

Table 2. Comparisons before and after subcutaneous tramadol (20 and 60 minutes)

Table 3. Verbal pain scale to a tramadol subcutaneous injection

The average pain according to the verbal scale at baseline was 8, after 20 minutes was 3; and following 60 minutes was 2 (Table 2). Only 6.5% of the patients required a second medication for persistent pain. 88% of the patients revealed three or less on the verbal pain scale during application of the subcutaneous medication (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Tramadol is a weak opioid with low affinity for receptors, but with activity in monoaminergic pathways by inhibiting the reuptake of norepinephrine and increasing the release of serotonin, providing an analgesic profile with fewer side-effects than pureopioids, making it more tolerable.[9,10]Classically, tramadol has been used parenterally with the presumption of greater analgesic potency bioavailability; however, there have been reported side-effects, most frequent nausea (6.1%), dizziness (4.6%), drowsiness (2.4%), tiredness/ fatigue (2.3%), sweating (1.9%), vomiting (1.7%) and dry mouth (1.6%), less common pruritus, subcutaneous nodules and seizures.[11–14]

The security profile of single doses or less than 24 hours administration is similar, leaving tramadol as a safe drug that can be used differently for rectal, intravenous, sublingual, muscular, oral, regional analgesia or subcutaneous infusion. These routes have been explored in postoperative pain, labor, abdominal pain, trauma and chronic conditions such as pain due to cancer and neuropatic pain.[15–18]

The subcutaneous route is used in emergency services because of its easy preparation and administration, especially because difficult vascular access may delay patient care.[19,20]A single 50 mg-SC dose of tramadol is a useful alternative in patients presenting to the ED for mild to moderate musculoskeletal trauma, with a significant reduction in pain on the verbal scale, with a success rate of 50% at 20 minutes and 75% at 60 minutes and a low incidence of adverse events or complications. Other studies[21]investigated subcutaneous tramadol for acute pain in the ED because of a broader range of causes. We focused on musculoskeletal causes since they are very common in our ED.

A subcutaneous alternative is safe and fast and helps to reduce the rate of unnecessary intravenous medication and to assist in patient's satisfaction in managing pain.[22–25]

In conclusion, a single subcutaneous 50 mg dose of tramadol is a useful and safe alternative in patients presenting to the emergency department for mild to moderate musculoskeletal trauma, with a significant reduction in pain at 20 and 60 minutes after application. Pain perception of the injection by patients supports its application in the emergency department.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:This study was approved by the ethical committee of the clinic prior to verbal patient consent and veri fi cation of tramadol blister for subcutaneous delivery authorized by the Instituto Nacional de Vigilancia de Medicamentos (INVIMA).

Con fl icts of interest:The authors declare that there is no con fl icts of interest relevant to the content of the article.

Contributors:Cardozo A proposed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. The authors declare no con fl icts of interest.

REFERENCES

1 Cordell WH, Keene KK, Giles BK, Jones JB, Jones JH, Brizendine EJ. The high prevalence of pain in emergency medical care. Am J Emerg Med 2002; 20: 165–169.

2 Todd KH, Ducharme J, Choiniere M, Crandall CS, Fosnocht DE, Homel P, et al. Pain in the emergency department: results of the pain and emergency medicine initiative (PEMI) multicenter study. J Pain 2007; 8: 460–466.

3 Singer AJ, Thode HC Jr. National analgesia prescribing patterns in emergency department patients with pain. J Burn Care Rehabil 2002; 23: 361–365.

4 Grant PS. Analgesia delivery in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2006; 24: 806–809.

5 Hansen K, Thom O, Rodda H, Price M, Jackson C, Bennetts S, et al. Impact of pain location, organ system and treating specialty on timely delivery of analgesia in emergency departments. Emerg Med Australas 2012; 24: 64–71.

6 Pines JM, Shofer FS, Isserman JA, Abbuhl SB, Mills AM. The effect of emergency department crowding on analgesia in patients with back pain in two hospitals. Acad Emerg Med 2010; 17: 276–283.

7 Pines JM, Hollander JE. Emergency department crowding is associated with poor care for patients with severe pain. Ann Emerg Med 2008; 51: 1–5.

8 Sills MR, Fairclough DL, Ranade D, Mitchell MS, Kahn MG. Emergency department crowding is associated with decreased quality of analgesia delivery for children with pain related to acute, isolated, long-bone fractures. Acad Emerg Med 2011; 18: 1330–1338.

9 Houmes RJ, Voets MA, Verkaaik A, Erdmann W, Lachmann B. Efficacy and safety of tramadol versus morphine for moderate and severe postoperative pain with special regard to respiratory depression. Anesth Analg 1992; 9: 23–28.

10 Vickers MD, O'Flaherty D, Szekely SM, Read M, Yoshizumi J. Tramadol: pain relief by an opioid without depression of respiration. Anaesthesia 1992; 47: 291–296.

11 Coskun HS, Ozbalci D, Sahin M. An unusual side-effect of tramadol: subcutaneous nodules. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006; 20: 1008–1009.

12 Ghislain PD, Wiart T, Bouhassoun N, Legout L, Alcaraz I, Caron J, et al. Toxic dermatitis caused by tramadol. Ann Dermatol Venereol 1999; 126: 38–40.

13 Farajidana H, Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Zamani N, Sanaei-Zadeh H. Tramadol-induced seizures and trauma. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2012; 16 Suppl 1: 34–37.

14 Langley PC, Patkar AD, Boswell KA, Benson CJ, Schein JR. Adverse event profile of tramadol in recent clinical studies of chronic osteoarthritis pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2010; 26: 239–251.

15 Neri E, Maestro A, Minen F, Montico M, Ronfani L, Zanon D, et al. Sublingual ketorolac versus sublingual tramadol for moderate to severe post-traumatic bone pain in children: a double-blind,randomised, controlled trial. Arch Dis Child 2013; 98: 721–724.

16 Hopkins D, Shipton EA, Potgieter D, Van derMerwe CA, Boon J, De Wet C, et al. Comparison of tramadol and morphine via subcutaneous PCA following major orthopaedic surgery. Can J Anaesth 1998; 45: 435–442.

17 Altunkaya H, Ozer Y, Kargi E, Ozkocak I, Hosnuter M, Demirel CB, et al. The postoperative analgesic effect of tramadol when used as subcutaneous local anesthetic. Anesth Analg 2004; 99: 1461–1464.

18 Pozos-Guillén Ade J, Martínez-Rider R, Aguirre-Bañuelos P, Arellano-Guerrero A, Hoyo-Vadillo C, Pérez-Urizar J. Analgesic efficacy of tramadol by route of administration in a clinical model of pain. Proc West Pharmacol Soc 2005; 48: 61–64.

19 Wittig MD. IV access difficulty: incidence and delays in an urban emergency department. J Emerg Med 2012; 42: 483–487.

20 Nowak RM, Tomlanovich MC. Venous cutdowns in the emergency department. JACEP 1979; 8: 245–246.

21 Palop E, Santamarin F, Gálvez R. Efecto analgésico de la administración de tramadol por vía subcutánea en dolor agudo. Rev Soc Esp Dolor 1998; 5: 120–124.

22 Limm EI, Fang X, Dendle C, Stuart RL, Egerton Warburton D. Half of all peripheral intravenous lines in an Australian tertiary emergency department are unused: pain with no gain? Ann Emerg Med 2013; 62: 521–525.

23 Bhakta HC, Marco CA. Pain management: association with patient satisfaction among emergency department patients. J Emerg Med 2014; 46: 456–464.

24 Downey LV, Zun LS. Pain management in the emergency department and its relationship to patient satisfaction. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2010; 3: 326–330.

25 Todd KH, Funk KG, Funk JP, Bonacci R. Clinical significance of reported changes in pain severity. Ann Emerg Med 1996; 27: 485–489.

26 Grond S, Sablotzki A. Clinical pharmacology of tramadol. Clin Pharmacokinet 2004; 43: 879–923.

Received March 11, 2014

Accepted after revision August 10, 2014

World J Emerg Med 2014;5(4):275–278

10.5847/wjem.j.issn.1920–8642.2014.04.006

World journal of emergency medicine2014年4期

World journal of emergency medicine2014年4期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Instructions for Authors

- A man with a fracture from minor trauma

- A minimally invasive multiple percutaneous drainage technique for acute necrotizing pancreatitis

- Effects of mild hypothermia on the ROS and expression of caspase-3 mRNA and LC3 of hippocampus nerve cells in rats after cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- Simvastatin inhibits apoptosis of endothelial cells induced by sepsis through upregulating the expression of Bcl-2 and downregulating Bax

- Heat-related illness in Jinshan District of Shanghai: A retrospective analysis of 70 patients